Good Pharmacovigilance Practices for the Americas ISBN 978-92-75-13160-2 PANDRH Technical Document Nº 5 Pan American Network on Drug Regulatory Harmonization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Statistics (Part 2): Interpreting Study Results

Statistical Notes II Descriptive statistics (Part 2): Interpreting study results A Cook and A Sheikh he previous paper in this series looked at ‘baseline’. Investigations of treatment effects can be descriptive statistics, showing how to use and made in similar fashion by comparisons of disease T interpret fundamental measures such as the probability in treated and untreated patients. mean and standard deviation. Here we continue with descriptive statistics, looking at measures more The relative risk (RR), also sometimes known as specific to medical research. We start by defining the risk ratio, compares the risk of exposed and risk and odds, the two basic measures of disease unexposed subjects, while the odds ratio (OR) probability. Then we show how the effect of a disease compares odds. A relative risk or odds ratio greater risk factor, or a treatment, can be measured using the than one indicates an exposure to be harmful, while relative risk or the odds ratio. Finally we discuss the a value less than one indicates a protective effect. ‘number needed to treat’, a measure derived from the RR = 1.2 means exposed people are 20% more likely relative risk, which has gained popularity because of to be diseased, RR = 1.4 means 40% more likely. its clinical usefulness. Examples from the literature OR = 1.2 means that the odds of disease is 20% higher are used to illustrate important concepts. in exposed people. RISK AND ODDS Among workers at factory two (‘exposed’ workers) The probability of an individual becoming diseased the risk is 13 / 116 = 0.11, compared to an ‘unexposed’ is the risk. -

Risk Factors Associated with Maternal Age and Other Parameters in Assisted Reproductive Technologies - a Brief Review

Available online at www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2017, 8(2):15-19 ISSN : 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Risk Factors Associated with Maternal Age and Other Parameters in Assisted Reproductive Technologies - A Brief Review Shanza Ghafoor* and Nadia Zeeshan Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Gujrat, Hafiz Hayat Campus, Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan ABSTRACT Assisted reproductive technology is advancing at fast pace. Increased use of ART (Assisted reproductive technology) is due to changing living standards which involve increased educational and career demand, higher rate of infertility due to poor lifestyle and child conceivement after second marriage. This study gives an overview that how advancing age affects maternal and neonatal outcomes in ART (Assisted reproductive technology). Also it illustrates how other factor like obesity and twin pregnancies complicates the scenario. The studies find an increased rate of preterm birth .gestational hypertension, cesarean delivery chances, high density plasma, Preeclampsia and fetal death at advanced age. The study also shows the combinatorial effects of mother age with number of embryos along with number of good quality embryos which are transferred in ART (Assisted reproductive technology). In advanced age women high clinical and multiple pregnancy rate is achieved by increasing the number along with quality of embryos. Keywords: Reproductive techniques, Fertility, Lifestyle, Preterm delivery, Obesity, Infertility INTRODUCTION Assisted reproductive technology actually involves group of treatments which are used to achieve pregnancy when patients are suffering from issues like infertility or subfertility. The treatments can involve invitro fertilization [IVF], intracytoplasmic sperm injection [ICSI], embryo transfer, egg donation, sperm donation, cryopreservation, etc., [1]. -

Clarifying Questions About “Risk Factors”: Predictors Versus Explanation C

Schooling and Jones Emerg Themes Epidemiol (2018) 15:10 Emerging Themes in https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-018-0080-z Epidemiology ANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE Open Access Clarifying questions about “risk factors”: predictors versus explanation C. Mary Schooling1,2* and Heidi E. Jones1 Abstract Background: In biomedical research much efort is thought to be wasted. Recommendations for improvement have largely focused on processes and procedures. Here, we additionally suggest less ambiguity concerning the questions addressed. Methods: We clarify the distinction between two confated concepts, prediction and explanation, both encom- passed by the term “risk factor”, and give methods and presentation appropriate for each. Results: Risk prediction studies use statistical techniques to generate contextually specifc data-driven models requiring a representative sample that identify people at risk of health conditions efciently (target populations for interventions). Risk prediction studies do not necessarily include causes (targets of intervention), but may include cheap and easy to measure surrogates or biomarkers of causes. Explanatory studies, ideally embedded within an informative model of reality, assess the role of causal factors which if targeted for interventions, are likely to improve outcomes. Predictive models allow identifcation of people or populations at elevated disease risk enabling targeting of proven interventions acting on causal factors. Explanatory models allow identifcation of causal factors to target across populations to prevent disease. Conclusion: Ensuring a clear match of question to methods and interpretation will reduce research waste due to misinterpretation. Keywords: Risk factor, Predictor, Cause, Statistical inference, Scientifc inference, Confounding, Selection bias Introduction (2) assessing causality. Tese are two fundamentally dif- Biomedical research has reached a crisis where much ferent questions, concerning two diferent concepts, i.e., research efort is thought to be wasted [1]. -

Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points to Consider for Paediatric Safety Profiling and Protocol Development: a Scoping Review

pharmaceutics Review Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points to Consider for Paediatric Safety Profiling and Protocol Development: A Scoping Review Beate Aurich 1 and Evelyne Jacqz-Aigrain 1,2,* 1 Department of Pharmacology, Saint-Louis Hospital, 75010 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Paris University, 75010 Paris, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Translational paediatric drug development includes the exchange between basic, clinical and population-based research to improve the health of children. This includes the assessment of treatment related risks and their management. The objectives of this scoping review were to search and summarise the literature for practical guidance on how to establish a paediatric safety specification and its integration into a paediatric protocol. PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and websites of regulatory authorities and learned societies were searched (up to 31 December 2020). Retrieved citations were screened and full texts reviewed where applicable. A total of 3480 publica- tions were retrieved. No article was identified providing practical guidance. An introduction to the practical aspects of paediatric safety profiling and protocol development is provided by combining health authority and learned society guidelines with the specifics of paediatric research. The paedi- atric safety specification informs paediatric protocol development by, for example, highlighting the Citation: Aurich, B.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E. need for a pharmacokinetic study prior to a paediatric trial. It also informs safety related protocol Drug Safety in Translational Paediatric Research: Practical Points sections such as exclusion criteria, safety monitoring and risk management. In conclusion, safety to Consider for Paediatric Safety related protocol sections require an understanding of the paediatric safety specification. -

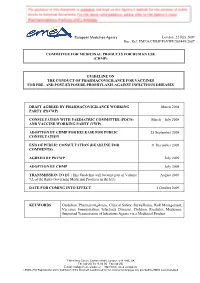

Guideline on the Conduct of Pharmacovigilance for Vaccines for Pre- and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Against Infectious Diseases

European Medicines Agency London, 22 July 2009 Doc. Ref. EMEA/CHMP/PhVWP/503449/2007 COMMITTEE FOR MEDICINAL PRODUCTS FOR HUMAN USE (CHMP) GUIDELINE ON THE CONDUCT OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE FOR VACCINES FOR PRE- AND POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST INFECTIOUS DISEASES DRAFT AGREED BY PHARMACOVIGILANCE WORKING March 2008 PARTY (PhVWP) CONSULTATION WITH PAEDIATRIC COMMITTEE (PDCO) March – July 2008 AND VACCINE WORKING PARTY (VWP) ADOPTION BY CHMP FOR RELEASE FOR PUBLIC 25 September 2008 CONSULTATION END OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION (DEADLINE FOR 31 December 2008 COMMENTS) AGREED BY PhVWP July 2009 ADOPTION BY CHMP July 2009 TRANSMISSION TO EC (This Guideline will become part of Volume August 2009 9A of the Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the EU). DATE FOR COMING INTO EFFECT 1 October 2009 KEYWORDS Guideline, Pharmacovigilance, Clinical Safety, Surveillance, Risk Management, Vaccines, Immunisation, Infectious Diseases, Children, Paediatric Medicines, Suspected Transmission of Infectious Agents via a Medicinal Product 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.europa.eu ©EMEA 2009 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged GUIDELINE ON THE CONDUCT OF PHARMACOVIGILANCE FOR VACCINES FOR PRE- AND POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS AGAINST INFECTIOUS DISEASES TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY_______________________________________________________ 3 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ -

Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning

Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) April 2005 ICH Guidance for Industry E2E Pharmacovigilance Planning Additional copies are available from: Office of Training and Communication Division of Drug Information, HFD-240 Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 (Tel) 301-827-4573 http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/index.htm Office of Communication, Training and Manufacturers Assistance, HFM-40 Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 1401 Rockville Pike, Rockville, MD 20852-1448 http://www.fda.gov/cber/guidelines.htm. (Tel) Voice Information System at 800-835-4709 or 301-827-1800 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) April 2005 ICH Contains Nonbinding Recommendations TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION (1, 1.1) ................................................................................................... 1 A. Background (1.2) ..................................................................................................................2 B. Scope of the Guidance (1.3)...................................................................................................2 II. SAFETY SPECIFICATION (2) ..................................................................................... -

2020 Standards for Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services

2020 Standards for Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services The International Network of Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services The International HPH Secretariat is based out of the office of OptiMedis AG: Burchardstrasse 17 20095 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 40 22621149-0 Fax: +49 40 22621149-14 Email: [email protected] © The International Network of Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services 2020 The International Network of Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services welcomes requests for permission to translate or reproduce this document in part or full. Please seek formal permission from the International HPH Secretariat. Recommended citation: International Network of Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services. 2020 Standards for Health Promoting Hospitals and Health Services. Hamburg, Germany: International HPH Network; December, 2020. Acknowledgements This document is the result of the efforts of many individuals and groups dedicated to the implementation of health promotion in and by hospitals and health services. We would like to thank members of the International HPH Network for their support of and input to the development process and all former and current leaders and members of HPH Task Forces and Working Groups for the production of standards on which this comprehensive standards set is based. Special thanks are due to National and Regional HPH Network Coordinators, subject experts, Standing Observers, and our Governance Board who devoted their time and provided invaluable input during consultation processes. We would further like to acknowledge Dr. Rainer Christ, Ms. Birgit Metzler, Ms. Keriin Katsaros, Dr. Sally Fawkes, and Prof. Margareta Kristenson who advised on the process leading to this document and critically assessed its content. -

The French Health Care System

The french health care system The french health care system VICTOR RODWIN PROFESSOR OF HEALTH POLICY AND MANAGEMENT WAGNER SCHOOL OF PUBLIC SERVICE, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY NEW YORK, USA ABSTRACT: The French health care system is a model of national health insurance (NHI) that provides health care coverage to all legal residents. It is an example of public social security and private health care financing, combined with a public-private mix in the provision of health care services. The French health care system reflects three underlying political values: liberalism, pluralism and solidarity. This article provides a brief overview of how French NHI evolved since World War II; its financing health care organization and coverage; and most importantly, its overall performance. ntroduction. Evolution, coverage, financing and organization The French health care system is a model of national health Evolution: French NHI evolved in stages and in response to Iinsurance (NHI) that provides health care coverage to all legal demands for extension of coverage. Following its original passage, residents. It is not an example of socialized medicine, e.g. Cuba. in 1928, the NHI program covered salaried workers in industry and It is not an example of a national health service, as in the United commerce whose wages were under a low ceiling (Galant, 1955). Kingdom, nor is it an instance of a government-run health care In 1945, NHI was extended to all industrial and commercial workers system like the United States Veterans Health Administration. and their families, irrespective of wage levels. The extension of French NHI, in contrast, is an example of public, social security and coverage took the rest of the century to complete. -

Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel

Core Concepts for Hand Hygiene: Clean Hands for Healthcare Personnel 1 Presenter Russ Olmsted, MPH, CIC Director, Infection Prevention & Control Trinity Health, Livonia, MI Contributions by Heather M. Gilmartin, NP, PhD, CIC Denver VA Medical Center University of Colorado Laraine Washer, MD University of Michigan Health System 2 Learning Objectives • Outline the importance of effective hand hygiene for protection of healthcare personnel and patients • Describe proper hand hygiene techniques, including when various techniques should be used 3 Why is Hand Hygiene Important? • The microbes that cause healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) can be transmitted on the hands of healthcare personnel • Hand hygiene is one of the MOST important ways to prevent the spread of infection 1 out of every 25 patients has • Too often healthcare personnel do a healthcare-associated not clean their hands infection – In fact, missed opportunities for hand hygiene can be as high as 50% (Chassin MR, Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf, 2015; Yanke E, Am J Infect Control, 2015; Magill SS, N Engl J Med, 2014) 4 Environmental Surfaces Can Look Clean but… • Bacteria can survive for days on patient care equipment and other surfaces like bed rails, IV pumps, etc. • It is important to use hand hygiene after touching these surfaces and at exit, even if you only touched environmental surfaces Boyce JM, Am J Infect Control, 2002; WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, WHO, 2009 5 Hands Make Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Other Microbes Mobile (Image from CDC, Vital Signs: MMWR, 2016) 6 When Should You Clean Your Hands? 1. Before touching a patient 2. -

Ecological Impacts of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: More Transparency – Better Protection of the Environment

Ecological Impacts of Veterinary Pharmaceuticals: More Transparency – Better Protection of the Environment Avoiding Environmental Pollution from Veterinary Pharmaceuticals To reduce the contamination of air, soil, and bodies of pharmaceuticals more stringently, monitoring systematically water caused by veterinary medicinal products used in their occurrence in the environment, converting animal hus- agriculture and livestock farming, effective measures bandry practices to preserve animals’ health with a minimal must be taken throughout the entire life cycle of these use of antibiotics, and enforcing legal regulations to ensure products – from production and authorisation to appli- implementation of all the measures outlined here. cation and disposal. In the context of the revision of veterinary medicinal products All stakeholders – whether they are farmers, veterinarians, legislation that is currently underway, this background paper consumers, or political decision makers – are called upon focuses on three measures that would contribute to mak- to contribute to reducing contamination of the environment ing information on the occurrence of veterinary drugs in the caused by pharmaceutical residues and to improving pro- environment and their eco-toxicological effects more widely tection of the environment and human health. Appropriate available and enhance protection of the environment from measures include establishing “clean” production plants, contamination with veterinary pharmaceuticals. developing pharmaceuticals with reduced environmental -

Promoting Hygiene

74 CHAPTER 9 Promoting hygiene The goal of hygiene promotion is to help people to understand and develop good hygiene practices, so as to prevent disease and promote positive atti- tudes towards cleanliness. Several community development activities can be used to achieve this goal, including education and learning programmes, encouraging community management of environmental health facilities, and social mobilization and organization. Hygiene promotion is not simply a matter of providing information. It is more a dialogue with communities about hygiene and related health problems, to encourage improved hygiene practices. Some key steps for establishing a hygiene promotion project, possibly with support from an outside agency, are listed in the text box below. Establishing a hygiene promotion project • Evaluate whether current hygiene practices are good/safe. • Plan which good hygiene practices to promote. • Implement a health promotion programme that meets community needs and is understandable by everyone. • Monitor and evaluate the programme to see whether it is meeting targets. 9.1 Assessing hygiene practices To assess whether good hygiene is practised by your community, some of the methods discussed in section 2.2 can be used. It is particularly important to identify behaviours that spread pathogens. The following are the riskiest behaviours: • The unsafe disposal of faeces. • Not washing hands with soap after defecating. • The unsafe collection and storage of water. CHAPTER 9. PROMOTING HYGIENE 75 Key questions for assessing hygiene -

Chapter 9: Monitoring, Surveillance, and Investigation of Health Threats

Chapter 9: Monitoring, surveillance, and investigation of health threats SUMMARY POINTS · Monitoring, surveillance and investigation of health threats are vital capabilities for an effective health system. The International Health Regulations (2005) require countries to maintain an integrated, national system for public health surveillance and response, and set out the core capabilities that countries are required to achieve. · Systematic monitoring of serious infectious diseases and other conditions is typically achieved through notifiable diseases legislation based on clinical observation and laboratory confirmation. Clinical and laboratory-based surveillance also provides the basis for systematic collection of vital statistics (births, deaths, causes of death), and may extend to the reporting and analysis of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases and injuries. Systematic collection of these data informs the allocation of resources and facilitates evaluation of community-based and population-level prevention strategies. · Clinical and laboratory surveillance are passive systems that may be enhanced by sentinel surveillance and/or community-based surveillance strategies that rely on a wider range of people, including non-medical personnel. Suspected cases identified in this way must be treated with respect, protected from discrimination, with diagnosis confirmed by qualified health workers at the earliest opportunity. · A significant degree of stigma may attach to some diseases, such as HIV, sexually transmitted infections and diabetes. Notifiable diseases legislation should require the protection of personal information, and clearly define any exceptions. Concerns about discrimination and breach of privacy may be addressed by requiring certain diseases to be reported on an anonymous or de- identified basis. · In some countries, legislation or regulations may be used to establish or enhance a comprehensive public health surveillance system.