Createworld 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studio Showcase

Contacts: Holly Rockwood Tricia Gugler EA Corporate Communications EA Investor Relations 650-628-7323 650-628-7327 [email protected] [email protected] EA SPOTLIGHTS SLATE OF NEW TITLES AND INITIATIVES AT ANNUAL SUMMER SHOWCASE EVENT REDWOOD CITY, Calif., August 14, 2008 -- Following an award-winning presence at E3 in July, Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: ERTS) today unveiled new games that will entertain the core and reach for more, scheduled to launch this holiday and in 2009. The new games presented on stage at a press conference during EA’s annual Studio Showcase include The Godfather® II, Need for Speed™ Undercover, SCRABBLE on the iPhone™ featuring WiFi play capability, and a brand new property, Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure. EA Partners also announced publishing agreements with two of the world’s most creative independent studios, Epic Games and Grasshopper Manufacture. “Today’s event is a key inflection point that shows the industry the breadth and depth of EA’s portfolio,” said Jeff Karp, Senior Vice President and General Manager of North American Publishing for Electronic Arts. “We continue to raise the bar with each opportunity to show new titles throughout the summer and fall line up of global industry events. It’s been exciting to see consumer and critical reaction to our expansive slate, and we look forward to receiving feedback with the debut of today’s new titles.” The new titles and relationships unveiled on stage at today’s Studio Showcase press conference include: • Need for Speed Undercover – Need for Speed Undercover takes the franchise back to its roots and re-introduces break-neck cop chases, the world’s hottest cars and spectacular highway battles. -

Game Console Rating

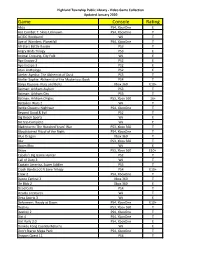

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

![Createworld 2011 Proceedings [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8165/createworld-2011-proceedings-pdf-1388165.webp)

Createworld 2011 Proceedings [PDF]

CreateWorld 2011 Proceedings CreateWorld11 Conference 28 November - 30 November 2011 Griffith University, Brisbane Queensland Australia Editors Michael Docherty :: Queensland University of Technology Matt Hitchcock :: Griffith University, Qld Conservatorium CreateWorld 2011 Proceedings of the CreateWorld11 Conference 20 - 30 November Griffith University, Brisbane Queensland Australia Editor Michael Docherty :: Queensland University of Technology Matt HItchcock :: Griffith University Web Content Editor Andrew Jeffrey http://www.auc.edu.au/Create+World+2011 ISBN: 978-0-947209-38-4 © Copyright 2011, Apple University Consortium Australia, and individual authors. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without the written permission of the copyright holders. CreateWorld 2011 Proceedings of the CreateWorld11 Conference 28 - 30 November, 2011 Griffith University, Brisbane Queensland Australia Contents Robert Burrell, Queensland Conservatorium, Griffith University 1 Zoomusicology, Live Performance and DAW [email protected] Dean Chircop, Griffith Film School (Film and Screen Media Productions) 10 The Digital Cinematography Revolution & 35mm Sensors: Arriflex Alexa, Sony PMW-F3, Panasonic AF100, Sony HDCAM HDW-750 and the Cannon 5D DSLR. [email protected] Kim Cunio, Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University 18 ISHQ: A collaborative film and music project – art music and image as an installation, joint art as boundary crossing. [email protected]; Louise Harvey, -

![[Full PDF] How to Manual on Skate 3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6891/full-pdf-how-to-manual-on-skate-3-1946891.webp)

[Full PDF] How to Manual on Skate 3

How To Manual On Skate 3 Ps3 Download How To Manual On Skate 3 Ps3 Get the latest Skate 2 cheats, codes, unlockables, hints, Easter eggs, glitches, tips, tricks, hacks, downloads, trophies, guides, FAQs, walkthroughs, and more for PlayStation 3 (PS3). CheatCodes has all you need to win every game you play! Use the above links or scroll down see all to the PlayStation 3 cheats we have available for Skate 2. Download Skate 3 Ps3 Posted on 10 April، 2021 by games Skate 3 is the third installment in the Skate series of video games, developed by EA Black Box, and published by Electronic Arts. Skate 2 is the peak of the series, it's the first in the series to give you the ability to get off your skateboard and walk around the environment if necessary, also it has been updated to support custom soundtracks (PS3 version, always could on Xbox360) by going to the Playstation menu and selecting music from the OS. Mint Disc Playstation 3 Ps3 Skate. Skate 1 I First Game Free Postage. AU $17.24. Mint Disc Xbox 360 Skate 3 Works on Xbox One Free Postage Inc Manual. AU $30.50. Unlocks:New band t-shirt available Film:Sight Unseen -Stay in a No-Skate Zone -Get 2000 points - Nose Manual to Fliptrick to Nose Manual I did this at the lakeside area no-skate zone. Film:Ghetto Blasters -Do 3 grinds -Do 15 ft powerslide -720 total deg spin I did this at the lakeside area, doing the powerslide up and back down the loopy thing. -

1 Tricia Gugler

Tricia Gugler: Welcome to our first quarter fiscal 2009 earnings call. Today on the call we have John Riccitiello, our Chief Executive Officer; Eric Brown, our Chief Financial Officer; John Pleasants, our Chief Operating Officer; and Peter Moore, our President of EA SPORTS. Before we begin, I’d like to remind you that you may find copies of our SEC filings, our earnings release and a replay of this webcast on our web site at investor.ea.com. Shortly after the call we will post a copy of our prepared remarks on our website. Throughout this call we will present both GAAP and non-GAAP financial measures. Non-GAAP measures exclude the following items: • amortization of intangibles, • stock-based compensation, • acquired in-process technology, • restructuring charges, • certain litigation expenses, • losses on strategic investments, • the impact of the change in deferred net revenue related to certain packaged goods and digital content. In addition, starting with its fiscal 2009 results, the Company began to apply a fixed, long-term projected tax rate of 28% to determine its non-GAAP results. Prior to fiscal 2009, the Company’s non-GAAP financial results were determined by excluding the specific income tax effects associated with the non-GAAP items and the impact of certain one-time income tax adjustments. Our earnings release provides a reconciliation of our GAAP to non-GAAP measures. These non-GAAP measures are not intended to be considered in isolation from – a substitute for – or superior to – our GAAP results – and we encourage investors to consider all measures before making an investment decision. -

2014-07 EFF Gaming Exempiton Comment

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Docket No. 2014-07 Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Electronic Frontier Foundation Kendra Albert Mitch Stoltz (203) 424-0382 Corynne McSherry [email protected] Kit Walsh 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of copyright owners and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while facilitating innovation and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these comments, EFF represents the interests of gaming communities, archivists, and researchers who seek to preserve the functionality of video games abandoned by their manufacturer. 2. Proposed Class Addressed Proposed Class 23: Abandoned Software—video games requiring server communication Literary works in the form of computer programs, where circumvention is undertaken for the purpose of restoring access to single-player or multiplayer video gaming on consoles, personal computers or personal handheld gaming devices when the developer and its agents have ceased to support such gaming. We ask the Librarian to grant an exemption to the ban on circumventing access controls applied to copyrighted works, 17 U.S.C. -

EA Unveils Eclectic Soundtracks for Skate It and Skate 2

EA Unveils Eclectic Soundtracks for Skate It and Skate 2 Track List Boasts Songs From Some of the Biggest and Most Influential Artists of All-Time Including Black Sabbath, Public Enemy, The Clash and Wu-Tang Clan REDWOOD CITY, Calif., Oct 23, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Black Box, an Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) studio, today revealed the soundtracks that will power the award-winning Skate It and Skate 2. These two skateboarding games bring the sport's incredible tricks, epic moves and high energy to gamers with all of the fun -- and none of the bruises! The 52 featured songs are from some of music's most influential and celebrated artists including Black Sabbath, Public Enemy, Judas Priest and Wu-Tang Clan. "The soundtracks for Skate It and Skate 2 builds upon last year's critically acclaimed Skate soundtrack," said Chris Parry, Associate Producer. "The songs reflect the culture of skateboarding, with some tracks picked by the pros themselves, and others coming straight out of iconic skate videos.Skateboarding today is an eclectic mix of people and influences and this is true of where we took this year's soundtracks. Look for some old school soul and funk, a few rock anthems, some good beats and a lot of classic punk!" "Skateboarding culture is like no other culture in the world and with that comes a unique sound of its own," said Steve Schnur, worldwide executive of music and marketing. "Our goal was to create two soundtracks that bring together classic acts and explosive new bands while fearlessly crossing all genres. -

The BG News April 11, 2008

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-11-2008 The BG News April 11, 2008 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 11, 2008" (2008). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7915. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7915 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ESTABLISHED 1920 A daily independent student press serving THE BG NEWS the campus and surrounding community Friday April 11,2008 Volume 101, Issue 157 WWWBGNEWSCOM A crisis off T-shirts that deserve a double-take A T-shirt project works to bring attention to violence committed against Wood County women Among other college transiticftsr^tudent's |hn3 religion can also be called into question WORKING WITH THE BUGS: Natural Resources Specialist Cinda Stutzman tends to the hummingbird and butterfly habitat located in Wintergarden Park. Losing a loyal By Kate Snyder than just somebody telling best friend Reporter them it's good for them. Columnist Ally And everybody practices When coming to college, the faith differently. A wooded area Blankartz chronicles obvious changes include dorm Some flourish by join- the last few days of her life, new classes, a new town ing organizations and get- dog, Millie, who went and different food. -

Space and Place As Expressive Categories in Videogames

Space and place as expressive categories in videogames A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Paul Martin School of Arts Brunel University August 2011 1 Abstract This thesis sets out to explore some of the ways in which videogames use space as a means of expression. This expression takes place in two registers: representation and embodiment. Representation is understood as a form of expression in which messages and ideas are communicated. Embodiment is understood as a form of expression in which the player is encouraged to take up a particular position in relation to the game. This distinction between representation and embodiment is useful analytically but the thesis attempts to synthesise these modes in order to account for the experience of playing videogames, where representation and embodiment are constantly happening and constantly influencing and shaping each other. Several methods are developed to analyse games in a way that brings these two modes to the fore. The thesis attempts to arrive at a number of spatial aesthetics of videogames by adapting methods from game studies, literary criticism, phenomenology, onomastics (the study of names), cartographic theory, choreography and architectural and urban formation analysis. 2 Table of Contents Abstract............................................................................................................................. 2 Table of Figures ................................................................................................................ 4 -

Tiger Woods Pga Tour 08 Manual Pc

Tiger Woods Pga Tour 08 Manual Pc Find great deals on eBay for Tiger Woods PGA Tour in Video Games. Woods PC game only survived the first decade, and since Tiger Woods PGA Tour 08. Forums for the EA SPORTS Rory McIlroy PGA TOUR. All off topic posts go here. 271, 1289, 08/19/2015 09:45:37 LittlestHobo33 · (Latest Reply). Cheats for Tiger Woods PGA Tour 08 for the PC. Use our Cheats, Tips, Walkthroughs, FAQs, and Guides to get the edge you need to win big, or unlock. to the reigning No. 1-ranked golfer after a 16-year run with Tiger Woods, publisher ElectronicThe old Tiger Woods PGA Tour series spanned 1998-2013. In 2013, EA Sports Metal Gear Solid 5's 'Quiet bug' is fixed on PS4 and PC. By Owen S. Good in Destiny by mywayneheavy on Sep 08, 2015. Polygon's Destiny. Cheats For "Tiger Woods PGA Tour 08" For PC (Voice Tutorial)(HD) How to Get Tiger. Naruko Episode 1 - Naruto x Shizune kyoryu sentai zyuranger episode 21. Conway Twitty Hello Darlin rar rapidshare tiger woods pga tour 08 game manual pc Tiger Woods Pga Tour 08 Manual Pc Read/Download After Tiger Woods 99 PGA Tour Golf was released, subsequent titles were named 1.2.9 Tiger Woods PGA Tour 07 (2006), 1.2.10 Tiger Woods PGA Tour 08 version, GamePro praised the screen layout, controls, and detailed graphics,. Recommendation: Scan your PC for TW2008.exe registry corruption TW2008.exe is a type of EXE file associated with Tiger Woods PGA Tour 08 developed automatically executes these instructions designed by a software developer (eg. -

Tactile Precision, Natural Movement and Haptic Feedback in 3D Virtual Spaces

A quest for the Holy Grail: Tactile precision, natural movement and haptic feedback in 3D virtual spaces Helen Farley Centre for Innovation and Educational Technologies (CEIT) and Teaching and Educational Development Institute (TEDI), The University of Queensland Caroline Steel Teaching and Education Development Institute (TEDI), The University of Queensland Three-dimensional immersive spaces such as those provided by virtual worlds, give unparalleled opportunities for learners to practically engage with simulated authentic settings that may be too expensive or too dangerous to experience in the real world. The potential afforded by these environments is severely constrained by the use of a keyboard and mouse moving in two dimensions. While most technologies have evolved rapidly in the early 21st century, the mouse and keyboard as standard navigation and interaction tools have not. However, talented teams from a range of disciplines are on serious quests to address this limitation. Their Holy Grail is to develop ways to interact with 3D immersive spaces using more natural human movements with haptic feedback. Applications would include the training of surgeons and musical conductors, training elite sports people and even physical rehabilitation. This paper reports on the cutting-edge technology projects that look most likely to provide a solution for this complex problem, including the Wiimote and the Microsoft’s Project Natal. Keywords: 3D, virtual worlds, haptic, Wii, immersion Introduction Although there is great fanfare about the potential of three-dimensional immersive spaces for application to higher education, there are still significant shortcomings in the available technologies that need to be addressed to reliably harness that potential. -

Hgzine Issue 17

FREE! NAVIGATE |01 Issue 17 | June 2008 REVIEWED! Everybody’s Golf 2 Verdict inside! HGFree Magazine For Handheld Gamers.Zine Read it, Print it, Send it to your mates… EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW! WIN! ONE OF FIVE CRASH BANDICOOT: COPIES OF SBK-08! MINDAll-new OVER shots and infoMUTANT REVIEW PREVIEW PREVIEW REVIEW Soul Bubbles SimCity The Legend Another DS gem? Creator Guitar Hero: of Spyro A whole city Dawn of the Dragon – flaming Iron Man On Tour Heavy metal! on your DS! Latest news and shots! hot news and shots CONTROL WWW.GAMERZINES.COM NAVIGATE |02 QUICK FINDER DON’T Every game’s just a click away! MISS! SONY PSP Crash Bandicoot: Doctor Who This month’s Crash Bandicoot: Mind over Mutant Ninja Gaiden Mind over Mutant Arkanoid DS Dragon Sword highlights Iron Man Dragon Quest: Looney Tunes: HGZine Everybody’s Golf 2 The Chapters Cartoon Concerto NINTENDO DS of the Chosen DS Reviews The Legend of Round-up There are some big names in this month’s issue SimCity Creator Soul Bubbles Kung Fu Panda Spyro: Dawn of MOBILE PHONE of your favourite handheld mag, including Find out why this is the next Lost in Blue 3 the Dragon News Guitar Hero: Soul Bubbles Reviews Crash, Spyro, Iron Man, Doctor Who, but there essential DS game to buy! Top Trumps: are a couple of surprises, too. On Tour For starters, we recommend that you check out Soul Bubbles if you’re looking for something MORE FREE MAGAZINES! LATEST ISSUES! a bit different on DS this month – it’s hugely CRASH BANDICOOT: entertaining and totally addictive.