6-Step Plan for Endurance Athletes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ryan Hall 5K Training Plan

RYAN HALL 5K TRAINING PLAN If you’re tackling another 5K and trying to get your best time, train for your next run with this 10-week plan from premier runner turned coach Ryan Hall. This plan is designed for intermediate and advanced runners. WEEK MON TUES WED THURS FRI SAT SUN Intervals Intervals Easy Run Easy Run Warm up, Run ¼ mile Easy Run Warm up, Run 1 mile at race Progression Run 30 minutes Rest 1 25 minutes at race pace, Rest 2 25 minutes pace, Rest 4 minutes, 60 minutes minutes, Repeat 5x Repeat 3x, Cool down (or cross-train) Intervals Warm up, Run 90 Pace Run Easy Run Easy Run seconds, Rest for 1 Easy Run Progression Run Warm up, Run 15 minutes 40 minutes Rest 2 minute, Run 3 minutes at 35 minutes 35 minutes at 10K pace, Cool down 70 minutes 5K pace, Rest 4 minutes, (or cross-train) Repeat 3x, Cool down Intervals Intervals Warm up, Run ½ mile, Warm up, Run 30 Easy Run Easy Run Easy Run Rest 2 minutes, Repeat 6x Progression Run seconds, Jog 1 minute, 45 minutes Rest 3 increasing speed by 45 minutes Repeat 10x without rest, 45 minutes 80 minutes 1-2 seconds each time, (or cross-train) Cool down Cool down Intervals Pace Run Warm up, Run 90 Warm up, Run 20 minutes Easy Run Easy Run seconds, Rest 1 minute, Easy Run Progression Run progressing from Marathon 30 minutes Rest 4 Run 3 minutes, Rest 4 25 minutes 25 minutes pace to Half-Marathon pace, 90 minutes minutes, Repeat 4x, (or cross-train) Cool down Cool down Intervals Intervals Easy Run Easy Run Warm up, Run 30 Easy Run Warm up, Run 1 mile, Progression Run seconds, Jog for 1 Rest -

Athletics Australia Almanac

HANDBOOK OF RECORDS & RESULTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to the following for their support and contribution to Athletics Australia and the production of this publication. Rankings Paul Jenes (Athletics Australia Statistician) Records Ronda Jenkins (Athletics Australia Records Officer) Results Peter Hamilton (Athletics Australia Track & Field Commission) Paul Jenes, David Tarbotton Official photographers of Athletics Australia Getty Images Cover Image Scott Martin, VIC Athletics Australia Suite 22, Fawkner Towers 431 St Kilda Road Melbourne Victoria 3004 Australia Telephone 61 3 9820 3511 Facsimile 61 3 9820 3544 Email [email protected] athletics.com.au ABN 35 857 196 080 athletics.com.au Athletics Australia CONTENTS 2006 Handbook of Records & Results CONTENTS Page Page Messages – Athletics Australia 8 Australian Road & Cross Country Championships 56 – Australian Sports Commission 10 Mountain Running 57 50km and 100km 57 Athletics Australia Life Members & Merit Awards 11 Marathon and Half Marathon 58 Honorary Life Members 12 Road Walking 59 Recipients of the Merit Award of Athletics Australia 13 Cross Country 61 All Schools Cross Country 63 2006 Results Australian All Schools & Youth Athletics Championships 68 Telstra Selection Trials & 84th Australian Athletics Championships 15 Women 69 Women 16 Men 80 Men 20 Schools Knockout National Final 91 Australian Interstate Youth (Under 18) Match 25 Cup Competition 92 Women 26 Plate Competition 96 Men 27 Telstra A-Series Meets (including 2007 10,000m Championships at Zatopek) 102 -

Matt Tegenkamp Matt Tegenkamp

T&FN INTERVIEW Matt Tegenkamp by Don Kopriva great experience, but overall, I think In his first year as a pro, Matt Tegenkamp I made the right decision. emerged as one of the brightest lights on the fast- T&FN: You didn’t have any fear improving U.S. distance scene in ’06. After an of the heat? It could be really hot in injury-plagued—yet successful—collegiate career Osaka and Beijing. at Wisconsin, he has now been enjoying a run of Tegenkamp: Yeah, it very well health. It showed in his racing, as he earned a No. could be. I’ve heard that it will be 2 U.S. Ranking and threatened the 13:00 barrier very humid. But I grew up in hot, in the 5000 while mixing it up strongly with the humid weather and that’s some- big boys on the European Circuit. thing that I’ve always run well in, The 5K will be his sole focus this year, and—bar- so it doesn’t bother me too much. ring a sudden change of plans—almost certainly T&FN: When you finished 5th in in ’08 as well. World Cross in ’01, did you have any He would have liked to run a 10K last year international awareness, in that you but it didn’t fit his training and racing schedule. and Dathan [Ritzenhein, who won As for a marathon, he wonders what he could the bronze] were kind of carrying the do and figures one banner for a talented group of young — Teg Facts — will be in the cards American distance runners? sometime down the Tegenkamp: I was kind of in •Personal: born Lee’s road, but he laughs my own little shell at that time. -

Long Distance Running Division

2006 Year-End Reports 28th Annual Meeting Reports from the Long Distance Running Division Men’s Long Distance Running Women’s Long Distance Running Masters Long Distance Running Cross Country Council Mountain, Ultra & Trail (MUT) Council Road Running Technical Council 97 National Officers, National Office Staff, Division and Committee Chairs 98 2006 Year-End Reports 28th Annual Meeting Men’s Long Distance Running B. USA National Championships 2005 USA Men's 10 km Championship – Food KEY POINTS World Senior Bowl 10k Mobile, AL – November 5, 2005 Update October 2005 to December 2005 http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/USA10kmCha As last year’s USATF Men’s LDR Annual Report mpionship-Men/ was written in October 2005 in order to meet A dominant display and new course record of publication deadlines for the Annual Convention, 28:11 for Dathan Ritzenhein to become the USA here are a few highlights of Men’s activities from National Champion. October 2005 through to the end of 2005. (Web site links provided where possible.) 2005 USATF National Club Cross Country Championships A. Team USA Events November 19, 2005 Genesee Valley Park - IAAF World Half Marathon Championships – Rochester, NY October 1, 2005, Edmonton, Canada http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/USATFClubX http://www.usatf.org/events/2005/IAAFWorldHalf CChampionships/ MarathonChampionships/ An individual win for Matt Tegenkamp, and Team Scores of 1st Hansons-Brooks D P 50 points th 6 place team United States - 3:11:38 - 2nd Asics Aggie R C 68 points USA Team Leader: Allan Steinfeld 3rd Team XO 121 points th 15 Ryan Shay 1:03:13 th 20 Jason Hartmann 1:03:32 C. -

Delaware Track & Field / Cross Country

DELAWARE TRACK & FIELD / CROSS COUNTRY ALUMNI NEWSLETTER / DECEMBER 2016 BLUE HEN: 2016 CROSS COUNTRY RECAP (‘blü/ ‘hen) n. 1: one who The 2016 Cross Country season left leads; one with aspirations of everyone eager for the future, as four of championship caliber; a team the top five scorers on the CAA, Mid player; one with a great Atlantic Regional, and ECAC tradition of excellence; one Championship teams will return in 2017. with a daring spirit; one who Freshman Mackenzie Jones led the Blue believes and overcomes. Hens in all but one of her races during adj.2: to be strong, focused the season, including an 18th place finish and dedicated; to be at the CAA Championships where she passionate and inspiring; to be was the second fastest freshman at the meet. part of a family. IN THIS ISSUE Mackenzie Jones led the Blue Hens for the majority the season - XC Recap and was the second overall freshman at the CAA Championships - New Assistant Coach - Newcomers - Indoor/Outdoor Schedules WELCOME NEW ASSISTANT COACH, RYAN WAITE - Save the Date! Ryan joins us from Brigham Young University, where he most STAY CONNECTED recently worked as the Director of Operations. Ryan has assisted or administered teams to four conference - www.bluehens.com championships, seven NCAA top-25 finishes, and one NCAA - Follow us on Twitter: podium finish. He also spent 2016 assisting in workouts for @DelawareTFXC U.S. Olympians Matthew Centrowitz, Galen Rupp, Shannon -Like us on Facebook: Rowbury and Jared Ward. As a collegiate athlete, he was a Blue Hens Cross Country and five-time All-American and three-time conference champion Track & Field and holds an 800 meter personal best of 1:46.83. -

August 27, 2018 the Bank of America Chicago Marathon Welcomes Strong American Field to Contend for the Crown at the 41St Annual

August 27, 2018 The Bank of America Chicago Marathon Welcomes Strong American Field to Contend for the Crown at the 41st Annual Event Olympic Gold Medalist and Two-Time Triathlon World Champion Gwen Jorgensen Joins Previously Announced Top Americans Galen Rupp, Jordan Hasay, Amy Cragg and Laura Thweatt CHICAGO – The Bank of America Chicago Marathon announced today that defending champion Galen Rupp and American superstars Jordan Hasay, Amy Cragg and Laura Thweatt will be Joined by a strong field of American runners at the 41st annual Bank of America Chicago Marathon. They will also go head-to-head with a mighty contingent of international athletes led by Mo Farah, past champions Abel Kirui and Dickson Chumba, 2017 runner-up Brigid Kosgei, and two- time third-place finisher and sub-2:20 runner Birhane Dibaba. “We are thrilled with this year’s overall elite field,” said Bank of America Chicago Marathon Executive Race Director Carey Pinkowski. “There is an incredible amount of talent and momentum on the American women’s side, and Rupp is leading a resurgence on the men’s side. These athletes are going to put on quite a show in October, and they are going to keep alive Chicago’s legacy of supporting and showcasing top U.S. athletes.” American Men’s Field Elkanah Kibet surprised race commentators during his marathon debut at the 2015 Bank of America Chicago Marathon when he bolted to the front of the elite field with 22 miles to go and put a 15-second gap on the field. The chase pack caught him at mile nine, and many suspected that Kibet’s bold move would spell disaster in the later stages of the race. -

The XXX Olympic Games London (GBR) - Sunday, Aug 12, 2012 Marathon - M FINAL

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The XXX Olympic Games London (GBR) - Sunday, Aug 12, 2012 Marathon - M FINAL ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 August 2012 - 11:00 Position Bib Athlete Country Mark . 1 3113 Stephen Kiprotich UGA 2:08:01 . 2 2304 Abel Kirui KEN 2:08:27 . 3 2302 Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich KEN 2:09:37 . 4 3225 Mebrahtom Keflezighi USA 2:11:06 . 5 1226 Marilson dos Santos BRA 2:11:10 . 6 2230 Kentaro Nakamoto JPN 2:11:16 . 7 3368 Cuthbert Nyasango ZIM 2:12:08 (PB) 8 1229 Paulo Roberto Paula BRA 2:12:17 . 9 2672 Henryk Szost POL 2:12:28 . 10 2139 Ruggero Pertile ITA 2:12:45 . 11 2971 Viktor Röthlin SUI 2:12:48 . 12 3147 Oleksandr Sitkovskyy UKR 2:12:56 (SB) 13 1222 Franck de Almeida BRA 2:13:35 . 14 2824 Aleksey Reunkov RUS 2:13:49 . 15 3367 Wirimai Juwawo ZIM 2:14:09 (SB) 16 1059 Michael Shelley AUS 2:14:10 . 17 2315 Emmanuel Kipchirchir Mutai KEN 2:14:49 . 18 2457 Rachid Kisri MAR 2:15:09 . 19 1593 Yared Asmerom ERI 2:15:24 . 20 1304 Dylan Wykes CAN 2:15:26 . 21 2629 Raúl Pacheco PER 2:15:35 . 22 1288 Eric Gillis CAN 2:16:00 . 23 2825 Dmitriy Safronov RUS 2:16:04 . 24 1615 Carles Castillejo ESP 2:16:17 . 25 2484 Iaroslav Musinschi MDA 2:16:25 . 26 2760 Marius Ionescu ROU 2:16:28 . 27 1285 Reid Coolsaet CAN 2:16:29 . 28 1041 Martin Dent AUS 2:16:29 (SB) 29 3146 Vitaliy Shafar UKR 2:16:36 . -

Stanford Cross Country Course

STANFORD ATHLETICS A Tradition of Excellence 116 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship award winners, including 10 in 2007-08. 109 National Championships won by Stanford teams since 1926. 95 Stanford student-athletes who earned All-America status in 2007-08. 78 NCAA Championships won by Stanford teams since 1980. 48 Stanford-affiliated athletes and coaches who represented the United States and seven other countries in the Summer Olympics held in Beijing, including 12 current student-athletes. 32 Consecutive years Stanford teams have won at least one national championship. 31 Stanford teams that advanced to postseason play in 2007-08. 19 Different Stanford teams that have won at least one national championship. 18 Stanford teams that finished ranked in the Top 10 in their respective sports in 2007-08. 14 Consecutive U.S. Sports Academy Directors’ Cups. 14 Stanford student-athletes who earned Academic All-America recognition in 2007-08. 9 Stanford student-athletes who earned conference athlete of the year honors in 2007-08. 8 Regular season conference championships won by Stanford teams in 2007-08. 6 Pacific-10 Conference Scholar Athletes of the Year Awards in 2007-08. 5 Stanford teams that earned perfect scores of 1,000 in the NCAA’s Academic Progress Report Rate in 2007-08. 3 National Freshmen of the Year in 2007-08. 3 National Coach of the Year honors in 2007-08. 2 National Players of the Year in 2007-08. 2 National Championships won by Stanford teams in 2007-08 (women’s cross country, synchronized swimming). 1 Walter Byers Award Winner in 2007-08. -

Leading Men at National Collegiate Championships

LEADING MEN AT NATIONAL COLLEGIATE CHAMPIONSHIPS 2020 Stillwater, Nov 21, 10k 2019 Terre Haute, Nov 23, 10k 2018 Madison, Nov 17, 10k 2017 Louisville, Nov 18, 10k 2016 Terre Haute, Nov 19, 10k 1 Justyn Knight (Syracuse) CAN Patrick Tiernan (Villanova) AUS 1 2 Matthew Baxter (Nn Ariz) NZL Justyn Knight (Syracuse) CAN 2 3 Tyler Day (Nn Arizona) USA Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN 3 4 Gilbert Kigen (Alabama) KEN Futsum Zienasellassie (NA) USA 4 5 Grant Fisher (Stanford) USA Grant Fisher (Stanford) USA 5 6 Dillon Maggard (Utah St) USA MJ Erb (Ole Miss) USA 6 7 Vincent Kiprop (Alabama) KEN Morgan McDonald (Wisc) AUS 7 8 Peter Lomong (Nn Ariz) SSD Edwin Kibichiy (Louisville) KEN 8 9 Lawrence Kipkoech (Camp) KEN Nicolas Montanez (BYU) USA 9 10 Jonathan Green (Gtown) USA Matthew Baxter (Nn Ariz) NZL 10 11 E Roudolff-Levisse (Port) FRA Scott Carpenter (Gtown) USA 11 12 Sean Tobin (Ole Miss) IRL Dillon Maggard (Utah St) USA 12 13 Jack Bruce (Arkansas) AUS Luke Traynor (Tulsa) SCO 13 14 Jeff Thies (Portland) USA Ferdinand Edman (UCLA) NOR 14 15 Andrew Jordan (Iowa St) USA Alex George (Arkansas) ENG 15 2015 Louisville, Nov 21, 10k 2014 Terre Haute, Nov 22, 10k 2013 Terre Haute, Nov 23, 9.9k 2012 Louisville, Nov 17, 10k 2011 Terre Haute, Nov 21, 10k 1 Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN Edward Cheserek (Oregon) KEN Kennedy Kithuka (Tx Tech) KEN Lawi Lalang (Arizona) KEN 1 2 Patrick Tiernan (Villanova) AUS Eric Jenkins (Oregon) USA Kennedy Kithuka (Tx Tech) KEN Stephen Sambu (Arizona) KEN Chris Derrick (Stanford) USA 2 3 Pierce Murphy -

2011 USA XC Program.Pdf

Coat Publications photos Welcome Jordan Hasay (1026) wins 2008 Jr. Women’s 6K as fans pack course. warm welcome from United States Track and Field to all athletes, media, sponsors and fans of the USA Cross Country Championships – America’s premier Cross Country running A event. The 2011 USA Cross Country Championships will be contested on February 5, 2011in San Diego, California and these championships will be hosted by the San Diego-Imperial Association of USA Track & Field. Participating athletes will be vying not only for national championship titles in the junior, senior and master’s categories, but also for positions on the US team that will compete at the 2011 IAAF World Cross Country Championships in Punta Umbra, Spain. Preceding this great competition will be a community race in which local runners will have the opportunity to compete on the same course as the Championship race. The attention of this nation will be focused on San Diego as our top American distance runners test their potential for National glory. A new generation of heroes and heroines will arise in preparation for the 2011 World Championships. To witness their achievements at this year’s National Cross Country championships reminds us that it takes each and every one of us to help make their dreams come true. San Diego can be proud of its contribution to USA Cross Country and it is this outstanding effort and support that brings America’s best distance athletes closer to their dreams. We also salute the many people who have given so generously of their time, talents and material resources to make this prestigious event a success. -

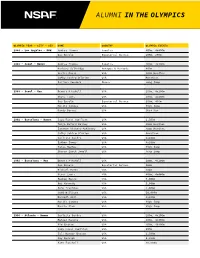

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

John Hancock Announces 2018 Boston Marathon U.S. Elite Field

For Release: Embargoed DRAFT until 11am ET CONTACT: Mary Kate Shea Phone: (617) 596-7382 Email: [email protected] John Hancock Announces 2018 Boston Marathon U.S. Elite Field 15 Member Team includes Olympic, World and Pan-American Medalists, Abbott World Marathon Majors Champions, and North American Record Holders BOSTON, MA, December 11, 2017-- John Hancock today announced its strongest U.S. Elite Team since its principal sponsorship began in 1986. The team, recruited to compete against an accomplished international field, will challenge for the coveted olive wreath on Patriots’ Day, April 16, 2018. Four-time Olympian and 2017 TCS New York City Marathon champion Shalane Flanagan headlines the field along with two-time Olympic medalist and 2017 Bank of America Chicago Marathon champion Galen Rupp. Joining them are Olympians Desiree Linden, Dathan Ritzenhein, Abdi Abdirahman, Deena Kastor, and Molly Huddle, the latter of whom is the North American 10,000m record holder. Also returning to Boston are Jordan Hasay and Shadrack Biwott. Hasay placed third at the 2017 Chicago Marathon, and set the American marathon debut record at Boston this year when she ran 2:23:00. Biwott finished as the second American and fourth overall in Boston this year. Serena Burla, Ryan Vail, Sara Hall, Scott Smith, Kellyn Taylor, and Andrew Bumbalough will also compete on the John Hancock U.S. Elite Team at the 122nd running of the Boston Marathon. “The 2018 John Hancock U.S. Elite Team represents a dedicated group of athletes who have consistently challenged themselves to compete with great success on the world stage,” said John Hancock Chief Marketing Officer Barbara Goose.