Victoria's Legislative Council Inquires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Accounts and Estimates Committee

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS AND ESTIMATES COMMITTEE 2021–22 Budget Estimates Melbourne—Monday, 21 June 2021 MEMBERS Ms Lizzie Blandthorn—Chair Mr James Newbury Mr Richard Riordan—Deputy Chair Mr Danny O’Brien Mr Sam Hibbins Ms Pauline Richards Mr David Limbrick Mr Tim Richardson Mr Gary Maas Ms Nina Taylor Monday, 21 June 2021 Public Accounts and Estimates Committee 1 WITNESSES Mr Colin Brooks, MP, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, Mr Nazih Elasmar, MLC, President of the Legislative Council, Mr Peter Lochert, Secretary, Department of Parliamentary Services, Ms Bridget Noonan, Clerk of the Legislative Assembly, and Mr Andrew Young, Clerk of the Legislative Council, Parliament of Victoria. The CHAIR: I declare open this hearing of the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee. I would like to begin by acknowledging the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land on which we are meeting. We pay our respects to them, their culture, their elders past, present and future and elders from other communities who may be here today. On behalf of the Parliament, the committee is conducting this Inquiry into the 2021–22 Budget Estimates. Its aim is to scrutinise public administration and finance to improve outcomes for the Victorian community. Please note that witnesses and members may remove their masks when speaking to the committee but must replace them afterwards. Mobile telephones and computers should be turned to silent. All evidence taken by this committee is protected by parliamentary privilege. Comments repeated outside this hearing may not be protected by this privilege. You will be provided with a proof version of the transcript to check. -

2010 Victorian State Election Summary of Results

2010 VICTORIAN STATE ELECTION 27 November 2010 SUMMARY OF RESULTS Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Results.......................................................................................... 3 Detailed Results by District ............................................................................... 8 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Result ........................................................ 24 Regional Summaries....................................................................................... 30 By-elections and Casual Vacancies ................................................................ 34 Legislative Council Results Summary of Results........................................................................................ 35 Incidence of Ticket Voting ............................................................................... 38 Eastern Metropolitan Region .......................................................................... 39 Eastern Victoria Region.................................................................................. 42 Northern Metropolitan Region ........................................................................ 44 Northern Victoria Region ................................................................................ 48 South Eastern Metropolitan Region ............................................................... 51 Southern Metropolitan Region ....................................................................... -

Surgical News May 2013 / Page 3

Surgicalthe royaL a ustraLasian News CoLLege of surgeons May 2013 Vol: 12 No:10 The Golden Nov/Dec Scalpel games 2011 - a test of surgical skill Value of the Audit Improving patient outcomes The College of Surgeons of Australia and New Zealand c ntents 10 Alcohol-fuelled violence Why we need to talk about it 16 Global Burden of Surgical Disease How surgeons can advance the agenda 18 A test of skill Medics compete in surgical battle of skills 22 Medico-Legal The ongoing saga of Jayant Patel 12 6 Relationships & Advocacy 22 Your Practice Card 8 Surgical Snips A new web facility for 14 Poison’d Chalice members 17 Dr BB G-loved 28 PD Workshops 25 International 33 Case Note Review Development 37 Curmudgeon’s Corner Continuing a vision in the 46 Book Club Pacific 26 Successful Scholar Ajay Iyengar’s research UpToDate® with heart To learn more or to 32 Morbidity Audit and Logbook Tool subscribe risk-free, visit This key tool continues learn.uptodate.com/UTD improvement for Fellows Or call +1-781-392-2000. Patients don’t just expect you to have all the right answers. 18 34 They expect you to have them right now. Fortunately, there’s SurgicalTHE ROYAL AUSTRALASIAN News COLLEGE OF SURGEONS MAY 2013 Vol: 12 No:10 UpToDate, the only reliable clinical resource that anticipates your The Golden Nov/Dec Correspondence to Surgical News should be sent to: Scalpel games 2011 - a test of surgical skill questions, then helps you find accurate answers quickly – often in [email protected] Letters to the Editor should be sent to: [email protected] the time it takes to go from one patient to another. -

Help Save Quality Disability Services in Victoria HACSU MEMBER CAMPAIGNING KIT the Campaign Against Privatisation of Public Disability Services the Campaign So Far

Help save quality disability services in Victoria HACSU MEMBER CAMPAIGNING KIT The campaign against privatisation of public disability services The campaign so far... How can we win a This is where we are up to, but we still have a long way to go • Launched our marginal seats campaign against the • We have been participating in the NDIS Taskforce, Andrews Government. This includes 45,000 targeted active in the Taskforce subcommittees in relation to phone calls to three of Victoria’s most marginal seats the future workforce, working on issues of innovation quality NDIS? (Frankston, Carrum and Bentleigh). and training and building support against contracting out. HACSU is campaigning to save public disability services after the Andrews Labor • Staged a pre-Christmas statewide protest in Melbourne; an event that received widespread media • We are strongly advocating for detailed workforce Government’s announcement that it will privatise disability services. There’s been a wide attention. research that looks at the key issues of workforce range of campaign activities, and we’ve attracted the Government’s attention. retention and attraction, and the impact contracting • Set up a public petition; check it out via out would have on retention. However, to win this campaign, and maintain quality disability services for Victorians, dontdisposeofdisability.org, don’t forget to make sure your colleagues sign! • We have put forward an important disability service we have to sustain the grassroots union campaign. This means, every member has to quality policy, which is about the need for ongoing contribute. • HACSU is working hard to contact families, friends and recognition of disability work as a profession, like guardians of people with disabilities to further build nursing and teaching, and the introduction of new We need to be taking collective and individual actions. -

An Analysis of the Failed Employee Voice System at the Bundaberg Hospital

Fatal consequences: an analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital Author Wilkinson, Adrian, Townsend, Keith, Graham, Tina, Muurlink, Olav Published 2015 Journal Title Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12061 Copyright Statement © 2015 Australian Human Resources Institute. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Fatal consequences: an analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, Volume 53, Issue 3, pages 265–280, 2015 which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12061. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving (http://olabout.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Section/id-828039.html) Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/157963 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Fatal Consequences: An analysis of the failed employee voice system at the Bundaberg Hospital ABSTRACT In this paper we discuss the failure of the employee voice system at the Bundaberg Base Hospital (BBH) in Australia. Surgeon Jayant Patel who was arrested over the deaths of patients on whom he operated when he was the Director of Surgery at the Hospital. Our interest is in the reasons the established employee voice mechanisms failed when employees attempted to bring to the attention of managers serious issues. Our data is based on an analysis of the sworn testimonies of participants who participated in two inquiries concerning these events. An analysis of the events with a particular focus on the failings of the voice system is presented. -

The Whistleno. 68, October 2011

“All that is needed for evil to prosper is for people of good will to do nothing”—Edmund Burke The Whistle No. 68, October 2011 Newsletter of Whistleblowers Australia “As part of my treatment, I need a nurse with a whistle.” Media watch O’Farrell steps in “I conclude that the justice of the Top court backs case requires that the state, the suc- for whistleblower cessful party, be entitled to its costs,” whistleblowers Britt Smith and Adam Bennett he said. Alexander Bratersky Australian Associated Press Ms Sneddon told the media she was Moscow Times, 1 July 2011 3 August 2011 facing the prospect of severe financial hardship because of the decision. The Constitutional Court on Thursday THE whistleblower in the Milton “It was supposed to be compensa- ruled that state employees cannot be Orkopoulos child sex case won’t have tion. How does that compensate what I punished for engaging in whistle- to pay the state’s legal costs after NSW have gone through, that I could be on blowing activities against their superi- Premier Barry O’Farrell stepped in to medication for life,” she told Fairfax ors. The court based its ruling on the save the woman he calls a “hero.” Radio Network. case of two state employees, a police Mr O’Farrell announced the bailout Then came the surprise twist. Mr officer and tax inspector, who both for Gillian Sneddon hours after a NSW O’Farrell announced just before 3pm were fired for criticizing their bosses. Supreme Court judge ruled against her to parliament that the state would pick “A state employee might express his in the costs decision on Wednesday. -

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Labor

AUSTRALIAN EDUCATION UNION Victorian Branch Victorian Labor MPs We want you to email the MP in the electoral district where your school is based. If your school is not in a Labor held area then please email a Victorian Labor upper house MP who covers your area from the separate list below. Click here if you need to look it up. Email your local MP and cc the Education Minister and the Premier Legislative Assembly MPs (lower house) ELECTORAL DISTRICT MP NAME MP EMAIL MP TELEPHONE Albert Park Martin Foley [email protected] (03) 9646 7173 Altona Jill Hennessy [email protected] (03) 9395 0221 Bass Jordan Crugname [email protected] (03) 5672 4755 Bayswater Jackson Taylor [email protected] (03) 9738 0577 Bellarine Lisa Neville [email protected] (03) 5250 1987 Bendigo East Jacinta Allan [email protected] (03) 5443 2144 Bendigo West Maree Edwards [email protected] 03 5410 2444 Bentleigh Nick Staikos [email protected] (03) 9579 7222 Box Hill Paul Hamer [email protected] (03) 9898 6606 Broadmeadows Frank McGuire [email protected] (03) 9300 3851 Bundoora Colin Brooks [email protected] (03) 9467 5657 Buninyong Michaela Settle [email protected] (03) 5331 7722 Activate. Educate. Unite. 1 Burwood Will Fowles [email protected] (03) 9809 1857 Carrum Sonya Kilkenny [email protected] (03) 9773 2727 Clarinda Meng -

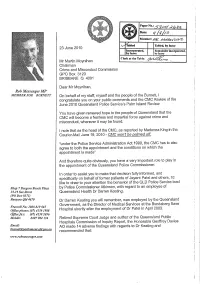

It / /Ja Member: 1

Paper No.: Date: it / /ja Member: 1 abled Tabled, by leave 23 June 2010 Incorporated, Remainder incorporated, by leave by leave Clerk at the Table: Mr Martin Moynihan Chairman Crime and Misconduct Commission GPO Box 3123 BRISBANE Q 4001 Dear Mr Moynihan, Rob Messenger MP MEMBER FOR B URNETT On behalf of my staff, myself and the people of the Burnett, I congratulate you on your public comments and the CMC Review of the June 2010 Queensland Police Service's Palm Island Review. You have given renewed hope to the people of Queensland that the CMC will become a fearless and impartial force against crime and misconduct, wherever it may be found. I note that as the head of the CMC, as reported by Madonna King in the Courier-Mail June 19, 2010.. CMG won't be palmed off "under the Police Service Administration Act 1990, the CIVIC has to also agree to both the appointment and the conditions on which the appointment is made" And therefore quite obviously, you have a very important role to play in the appointment of the Queensland Police Commissioner. In order to assist you to make that decision fully informed, and specifically on behalf of former patients of Jayent Patel and others, I'd like to draw to your attention the behavior of the QLD Police Service lead Strop 7Bargara Beacli -Plaza by Police Commissioner Atkinson, with regard to an employee of 15-19 See Street Queensland Health Dr Darren Keating. (PO Box 8371) Bargara Q1d4670 Dr Darren Keating you will remember, was employed by the Queensland Government, as the Director of Medical Services at the Bundaberg Base Freecall No. -

Presiding Officers on Behalf of the House Committee Pdf 174.1 KB

Mr Warren McCann Chair Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal Suite 1, Ground Floor, 1 Treasury Place EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 1 July 2020 Dear Mr McCann, Review of the Tribunal’s Members of Parliament Guidelines Thank you for the opportunity to provide a submission to the Tribunal’s review of the Members of Parliament (Victoria) Guidelines No. 2/2019 (“the Guidelines”). This is a submission on behalf of the Parliament’s House Committee. The House Committee is a cross-party committee established under the Parliamentary Committees Act 2003. Prior to the introduction of the Victorian Independent Remuneration Tribunal and Improving Parliamentary Standards Act 2019, the House Committee had a role in the development and adoption of guidelines (then known as the Members Guide) for the expenditure of Members’ electorate office and communications budgets. Following discussions of the House Committee, we submit the following issues, and the positions adopted by the committee on each issue, for your consideration. To be clear from the outset, this submission does not seek to increase Members’ budgets but rather suggests ways that existing resources can be used more effectively. Definition of ‘public duties’ You will recall that in a submission to the Tribunal dated 6 December 2019, the Speaker raised the matter of ensuring consistency between the Guidelines and the legislation, specifically as it related to the purpose of the Guidelines being to allow Members to communicate with their electorate in relation to the performance of their public duties. Whilst the Tribunal changed the Guidelines, feedback from Members and the Department of Parliamentary Services (in carrying out the duties of the Relevant Officer) is that the extent of the term ‘public duties’ should be clarified in the Guidelines. -

Annual Review, April 2008

SCRUTINY OF ACTS AND REGULATIONS COMMITTEE 56th Parliament Annual Review 2007 Ordered to be printed By Authority. Government Printer for the State of Victoria. N° 78 Session 2006-08 i Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee Parliament of Victoria, Australia Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee Annual Review 2007 Bibliography ISBN 978 0 7311 3027 8 ISSN 1440-5776 ii Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee Members Ms Carlo Carli MLA (Chairperson) Mr Ken Jasper MLA (Deputy Chairperson) Mr Colin Brooks MLA Mr Khalil Eideh MLC Mr Telmo Languiller MLA Mr Edward O’Donohue MLC Mrs Inga Peulich MLC Ms Jaala Pulford MLC Mr Ryan Smith MLA Staff Mr Andrew Homer, Senior Legal Adviser Ms Helen Mason, Legal Adviser, Regulations Mr Simon Dinsbergs, Business Support Officer Ms Sonya Caruana, Office Manager Consultant Associate Professor Jeremy Gans, Human Rights consultant Address Parliament House, Spring Street, Melbourne Victoria 3002 Telephone (03) 8682 2891 Facsimile (03) 8682 2858 Email [email protected] Internet www.parliament.vic.gov.au/sarc iii Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee iv Contents Committee membership iii Chairperson’s Introduction ix The Annual Review 1 Appendices 1 – Index of Bills Reported 2007 17 2 – Committee Comments classified by Terms of Reference 21 3 – Ministerial Correspondence 23 4 – Committee Reports and Other Papers 25 5 – Regulations considered in 2007 29 6 – Practice Notes 35 7 – Redundant and Unclear Legislation – Corporations laws 39 v Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee vi Terms of Reference Section 17 of the Parliamentary Committees Act 2003 sets out the statutory functions of the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee. -

Victoria New South Wales

Victoria Legislative Assembly – January Birthdays: - Ann Barker - Oakleigh - Colin Brooks – Bundoora - Judith Graley – Narre Warren South - Hon. Rob Hulls – Niddrie - Sharon Knight – Ballarat West - Tim McCurdy – Murray Vale - Elizabeth Miller – Bentleigh - Tim Pallas – Tarneit - Hon Bronwyn Pike – Melbourne - Robin Scott – Preston - Hon. Peter Walsh – Swan Hill Legislative Council - January Birthdays: - Candy Broad – Sunbury - Jenny Mikakos – Reservoir - Brian Lennox - Doncaster - Hon. Martin Pakula – Yarraville - Gayle Tierney – Geelong New South Wales Legislative Assembly: January Birthdays: - Hon. Carmel Tebbutt – Marrickville - Bruce Notley Smith – Coogee - Christopher Gulaptis – Terrigal - Hon. Andrew Stoner - Oxley Legislative Council: January Birthdays: - Hon. George Ajaka – Parliamentary Secretary - Charlie Lynn – Parliamentary Secretary - Hon. Gregory Pearce – Minister for Finance and Services and Minister for Illawarra South Australia Legislative Assembly January Birthdays: - Duncan McFetridge – Morphett - Hon. Mike Rann – Ramsay - Mary Thompson – Reynell - Hon. Carmel Zollo South Australian Legislative Council: No South Australian members have listed their birthdays on their website Federal January Birthdays: - Chris Bowen - McMahon, NSW - Hon. Bruce Bilson – Dunkley, VIC - Anna Burke – Chisholm, VIC - Joel Fitzgibbon – Hunter, NSW - Paul Fletcher – Bradfield , NSW - Natasha Griggs – Solomon, ACT - Graham Perrett - Moreton, QLD - Bernie Ripoll - Oxley, QLD - Daniel Tehan - Wannon, VIC - Maria Vamvakinou - Calwell, VIC - Sen. -

Legislative Council

8037 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday 4 June 2008 __________ The President (The Hon. Peter Thomas Primrose) took the chair at 11.00 a.m. The President read the Prayers. ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING AND ASSESSMENT AMENDMENT BILL 2008 BUILDING PROFESSIONALS AMENDMENT BILL 2008 STRATA MANAGEMENT LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2008 Bills received, and read a first time and ordered to be printed on motion by the Hon. Tony Kelly, on behalf of the Hon. Michael Costa. Motion by The Hon. Tony Kelly agreed to: That standing orders be suspended to allow the passing of the bills through all their remaining stages during the present or any one sitting of the House. Second reading set down as an order of the day for a later hour. CHINA EARTHQUAKE Motion by Reverend the Hon. Fred Nile agreed to: That this House: (a) recognises the human tragedy that is unfolding in the People's Republic of China, (b) expresses its sympathies to the victims of the earthquake in Sichuan Province, China, and (c) calls on State and Federal governments to offer, where practical, all available assistance to those suffering as a result of this disaster. STANDING COMMITTEE ON STATE DEVELOPMENT Government Response to Report The Hon. John Della Bosca tabled the Government's response to report No. 32, entitled "Aspects of Agriculture", dated 28 November 2007. Ordered to be printed on motion by the Hon. John Della Bosca. UNPROCLAIMED LEGISLATION The Hon. Eric Roozendaal tabled a list detailing all legislation unproclaimed 90 calendar days after assent as at 3 June 2008. PETITIONS Cooma Hospital Kidney Dialysis Service Petition requesting the provision of a kidney dialysis service for patients in the Cooma region, received from the Hon.