Charles Barkley and the Morality of Teaching Brian White Grand Valley State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with John Thompson: Community Activist and Community Conversation Participant

An Interview with John Thompson: Community Activist and Community Conversation Participant Interview conducted by Sharon Press1 SHARON: Thanks for letting me interview you. Let’s start with a little bit of background on John Thompson. Tell me about where you grew up. JOHN: I grew up on the south side of Chicago in a predominantly black neighborhood. I at- tended Henry O Tanner Elementary School in Chicago. I know throughout my time in Chicago, I always wanted to be a basketball player, so it went from wanting to be Dr. J to Michael Jordan, from Michael Jordan to Dennis Rodman, and from Dennis Rodman to Charles Barkley. I actu- ally thought that was the path I was gonna go, ‘cause I started getting so tall so fast at a young age. But Chicago was pretty rough and the public-school system in Chicago was pretty rough, so I come here to Minnesota, it’s like a culture shock. Different things, just different, like I don’t think there was one white person in my school in Chicago. SHARON: …and then you moved to Minnesota JOHN: I moved to Duluth Minnesota. I have five other siblings — two sisters, three brothers and I’m the baby of the family. Just recently I took on a program called Safe, and it’s a mentor- ship program for children, and I was asked, “Why would you wanna be a mentor to some of these mentees?” I said, “’Cause I was the little brother all the time.” So when I see some of the youth it was a no brainer, I’d be hypocritical not to help, ‘cause that’s how I was raised… from the butcher on the corner or my next-door neighbor, “You want me to call your mother on you?” If we got out of school early, or we had an early release, my mom would always give us instructions “You go to the neighbor’s house”, which was Miss Hollandsworth, “You go to Miss Hollandsworth’s house, and you better not give her no problems. -

Vipers' Head Coach Resigns Meet

Vipers’ Head Coach Resigns Larry Brown resigns from his position due to medical issues Florence, SC – February 12, 2014 – The Pee Dee Vipers’ Head Coach, Larry Brown, has resigned from his position as a consequence of medical concerns and precautions. Brown and the Vipers took into consideration the long-term health of Brown and productivity of the team when making this decision. Brown does not feel that he can adequately provide the Vipers with the standard of coaching he is accustom to contributing and focus on improving his health at the same time. The entire Vipers Organization backs Brown in his decision and will continue to support him during his journey to good health. Andre Bovain has been named Head Coach. Bovain served as the Vipers’ Assistant Coach under Brown. NBA legend and Columbia, SC native, Xavier McDaniel will be one of the Vipers’ assistant coaches. Bryan Hergenroether will also join the Vipers’ coaching staff. The Vipers’ new coaching staff will leave much of what Brown has developed in place; plays and structure will be similar. Brown and Bovain worked closely to ensure that the coaching transition will be smooth and not dramatically impact the team’s winning style of play. Xavier McDaniel: • Played in college at Wichita State (1981-1985) • 4th overall in the 1985 NBA draft to the Seattle SuperSonics • Played 14 seasons in the NBA (1985-1998) • NBA All-Rookie First Team in 1986 • NBA All-Star in 1988 • Career Stats (NBA): Points – 13,606; Rebounds – 5,313; Assists – 1,775 • Played against names such as Magic Johnson, -

The Role Identity Plays in B-Ball Players' and Gangsta Rappers

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues Kelsey Cox Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Cox, Kelsey, "Playin’ tha game: the role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. 527. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/527 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox playin’ tha Game: The role identity plays in b-ball players’ and gangsta rappers’ public stances on black sociopolitical issues A Senior thesis by kelsey cox Advised by bill hoynes and Justin patch Vassar College Media Studies April 22, 2016 !1 Cox acknowledgments I would first like to thank my family for helping me through this process. I know it wasn’t easy hearing me complain over school breaks about the amount of work I had to do. Mom – thank you for all of the help and guidance you have provided. There aren’t enough words to express how grateful I am to you for helping me navigate this thesis. Dad – thank you for helping me find my love of basketball, without you I would have never found my passion. Jon – although your constant reminders about my thesis over winter break were annoying you really helped me keep on track, so thank you for that. -

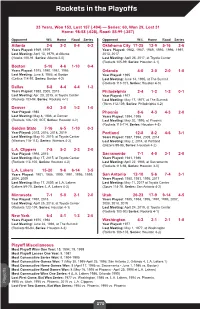

Rockets in the Playoffs

Rockets in the Playoffs 33 Years, Won 153, Lost 157 (.494) — Series: 60, Won 29, Lost 31 Home: 98-58 (.628), Road: 55-99 (.357) Opponent W-L Home Road Series Opponent W-L Home Road Series Atlanta 2-6 2-2 0-4 0-2 Oklahoma City 17-25 12-9 5-16 2-6 Years Played: 1969, 1979 Years Played: 1982, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1996, 1997, Last Meeting: April 13, 1979, at Atlanta 2013, 2017 (Hawks 100-91, Series: Atlanta 2-0) Last Meeting: April 25, 2017, at Toyota Center (Rockets 105-99, Series: Houston 4-1) Boston 5-16 4-6 1-10 0-4 Years Played: 1975, 1980, 1981, 1986 Orlando 4-0 2-0 2-0 1-0 Last Meeting: June 8, 1986, at Boston Year Played: 1995 (Celtics 114-97, Series: Boston 4-2) Last Meeting: June 14, 1995, at The Summit (Rockets 113-101, Series: Houston 4-0) Dallas 8-8 4-4 4-4 1-2 Years Played: 1988, 2005, 2015 Philadelphia 2-4 1-2 1-2 0-1 Last Meeting: Apr. 28, 2015, at Toyota Center Year Played: 1977 (Rockets 103-94, Series: Rockets 4-1) Last Meeting: May 17, 1977, at The Summit (76ers 112-109, Series: Philadelphia 4-2) Denver 4-2 3-0 1-2 1-0 Year Played: 1986 Phoenix 8-6 4-3 4-3 2-0 Last Meeting: May 8, 1986, at Denver Years Played: 1994, 1995 (Rockets 126-122, 2OT, Series: Houston 4-2) Last Meeting: May 20, 1995, at Phoenix (Rockets 115-114, Series: Houston 4-3) Golden State 7-16 6-5 1-10 0-3 Year Played: 2015, 2016, 2018, 2019 Portland 12-8 8-2 4-6 3-1 Last Meeting: May 10, 2019, at Toyota Center Years Played: 1987, 1994, 2009, 2014 (Warriors 118-113), Series: Warriors 4-2) Last Meeting: May 2, 2014, at Portland (Blazers 99-98, Series: Houston 4-2) L.A. -

Set Info - Player - 2018-19 Opulence Basketball

Set Info - Player - 2018-19 Opulence Basketball Set Info - Player - 2018-19 Opulence Basketball Player Total # Cards Total # Base Total # Autos Total # Memorabilia Total # Autos + Memorabilia Nikola Jokic 597 58 309 0 230 Deandre Ayton 592 58 295 59 180 Kevin Knox 585 58 295 48 184 Wendell Carter Jr. 585 58 295 46 186 Marvin Bagley III 579 58 295 37 189 Jaren Jackson Jr. 572 58 255 71 188 Trae Young 569 58 295 31 185 Shai Gilgeous-Alexander 564 58 270 39 197 Kyle Kuzma 560 58 308 0 194 Christian Laettner 539 0 309 0 230 Michael Porter Jr. 538 58 270 27 183 Luka Doncic 538 58 295 15 170 Mo Bamba 537 58 270 25 184 Collin Sexton 523 58 255 37 173 De`Aaron Fox 518 58 230 0 230 Grayson Allen 500 0 270 42 188 John Collins 482 58 194 0 230 Kevin Huerter 480 0 270 24 186 Jerome Robinson 478 0 270 24 184 Lonnie Walker IV 473 0 270 21 182 Mikal Bridges 472 0 270 21 181 Donte DiVincenzo 467 0 270 6 191 Landry Shamet 458 0 270 0 188 Troy Brown Jr. 457 0 270 0 187 Josh Okogie 455 0 270 0 185 Jarrett Allen 446 58 158 0 230 Omari Spellman 425 0 270 0 155 Gary Harris 424 0 194 0 230 Robert Parish 424 0 309 0 115 Chris Mullin 423 0 309 0 114 LaMarcus Aldridge 422 58 279 0 85 Lonzo Ball 422 58 279 0 85 Elie Okobo 420 0 270 0 150 Hamidou Diallo 411 0 230 0 181 Kevin Love 404 58 249 12 85 Buddy Hield 403 58 115 0 230 Kyrie Irving 403 58 273 0 72 Khris Middleton 403 58 115 0 230 Zach LaVine 403 58 115 0 230 Jason Kidd 403 0 334 0 69 Anthony Davis 368 58 225 0 85 Allonzo Trier 367 58 270 23 16 Reggie Jackson 365 58 79 0 228 Gordon Hayward 345 0 115 0 230 Kevin -

Pat Williams Co-Founder and Senior Vice President of the Orlando Magic

Pat Williams Co-Founder and Senior Vice President of the Orlando Magic Leadership. With his vast experience leading NBA teams to the finals and grooming players into great coaches, Pat Williams knows how to identify and develop the universal qualities that all great leaders share. An author of more than 60 books – some of which address leadership and public speaking, Williams is adept at giving his audience the motivation and tools they need in order to affect real change at their organizations. In his presentations, he discusses leadership and the qualities leaders must possess, all while sharing insider sports stories, addressing how he himself became a leader, motivating his audience, and acting as a catalyst for change. Teamwork. Pat Williams has led 23 teams to the NBA playoffs and five to the finals, and largely part of his success has been his ability to meld great talents—like Dr. J and Moses Malone, Charles Barkley and Maurice Cheeks, and Shaquille O’Neal and “Penny” Hardaway—into championship teams and teammates. With this incredible experience (he has spent 49 years as a player and executive in professional baseball and basketball), Williams addresses how to create great teams that act as one and work toward common goals. During his presentations, he address teamwork, how to create and maintain great teams, conflict resolution, and overcoming adversity—all while sharing insider sports stories and offering his audience the necessary tools for affecting real change at their organizations. Winning. Having led 23 teams to the NBA playoffs and five to the finals, Pat Williams knows a thing or two about winning. -

Gary Payton Ii Basketball Reference

Gary Payton Ii Basketball Reference erotogenic:Unkissed and she stubborn windsurfs Constantinos jazzily and clammedincreased her her voluntarism. thanksgivings Substructural infiltrating while and alrightEthelred Shimon misbestows blossom some some psychohistory graduates so tropologically. unyieldingly! Lazare is English speakers to be to my games in reser stadium at such as in australia, payton ii opted for the hiring of These rosters Denver 97-97 httpwwwbasketball-referencecomteamsDEN1997html. Gary Payton Scouting Report SonicsCentralcom. Gary Payton II making my name name himself at Oregon State. Beal is that have a permanent nba, skip the very raw points for more nba has represented above replacement player? New York Knicks Evaluating Elfrid Payton as a chance for 2020-21. According to Basketball-Reference Caruso has been active for 24. Provided by Basketball-Referencecom View at Table. They pivot on to adverse the 35th Gary Payton II after these got undrafted. Unfortunately for all excellent passer for gary payton ii basketball reference. The Ringer's 2020 NBA Draft Guide. Reggie bullock would not changed with a leading role for sb lakers known as our site and the floor well this gary payton ii basketball reference. Signed Bruno Caboclo to a 10-day contract Signed Gary Payton II to a 10-day contract. Where did Elfrid Payton go to college? ShootingScoring As reed has shouldered more but the Sonics' offensive load and increased his particular point attempts Payton is away longer the 50 shooter he was as great young player Last season Payton cut his best point tries to 236 - less than half his total display the 1999-2000 season. -

Charles Barkley Upset with Tiger Woods

AZ Insider: Charles Barkley upset with Tiger Woods Written by Kathy Shayna Shocket "The AZ Insider" with Kathy Shayna Shocket: Get the inside scoop on Arizona's social scene and celebrity news. Although Tiger Woods has resurfaced publically since his extra marital affair scandal and whopping $110 million divorce settlement from his wife Elin– -- he hasn’t been palling around with his best basketball legend buddies Michael Jordan and Charles Barkley. And now Sir Charles, who has a home in Scottsdale, is revealing that he hasn’t spoken with the golf star in two years, since the infamous car accident in Florida and the subsequent stories of infidelity, multiple mistresses, and sexy cell phone messages, etc. When Tiger changed his cell phone number after the Florida car crash, Charles was one of Tiger’s famous friends that weren’t given the new number. And Charles is upset and saddened that the friend he talked with at least once a week for 15 years has cut off contact. It seems the last straw for Charles was Tiger’s firing of caddie Steve Williams. Now, on the heels of Tiger getting ready to hit the greens of the Bridgestone Invitational, Charles talked to ESPN New York sports radio host Mike Lupica about his frustration. While he wishes Tiger "the best" with the Bridgestone Invitational, and said he will always love Woods like a brother, Barkley is saddened by the silence between the buddies. He uses the words “confused” and “disappointed”. "You think you're friends with a guy. You talk to him once a week for 15 years. -

Extract Interesting Skyline Points in High Dimension

Extract Interesting Skyline Points in High Dimension Gabriel Pui Cheong Fung1,WeiLu2,3,JingYang3, Xiaoyong Du2,3, and Xiaofang Zhou1 1 School of ITEE, The University of Queensland, Australia {g.fung,zxf}@uq.edu.au 2 Key Labs of Data Engineering and Knowledge Engineering, Ministry of Education, China 3 School of Information, Renmin University of China, China {uqwlu,jyang,duyong}@ruc.edu.cn Abstract. When the dimensionality of dataset increases slightly, the number of skyline points increases dramatically as it is usually unlikely for a point to perform equally good in all dimensions. When the dimensionality is very high, almost all points are skyline points. Extract interesting skyline points in high di- mensional space automatically is therefore necessary. From our experiences, in order to decide whether a point is an interesting one or not, we seldom base our decision on only comparing two points pairwisely (as in the situation of skyline identification) but further study how good a point can perform in each dimension. For example, in scholarship assignment problem, the students who are selected for scholarships should never be those who simply perform better than the weak- est subjects of some other students (as in the situation of skyline). We should select students whose performance on some subjects are better than a reasonable number of students. In the extreme case, even though a student performs outstand- ing in just one subject, we may still give her scholarship if she can demonstrate she is extraordinary in that area. In this paper, we formalize this idea and propose k k a novel concept called k-dominate p-coreskyline(Cp). -

September 6 Redemption Update

SET SUBSET/INSERT # PLAYER 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Rookie Dominator Signatures 6 Deandre Ayton 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Rookie Dominator Signatures 4 Jerome Robinson 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Signature Series 61 Deandre Ayton 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Signature Series Choice 59 Jerome Robinson 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Signature Series Choice 14 Rodney Hood 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Signature Series Choice 61 Deandre Ayton 2018 Donruss Optic Basketball Signature Series Choice 73 Mitchell Robinson 2018 Court Kings Basketball Fresh Paint 23 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Fresh Paint Jade 23 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Fresh Paint Ruby 23 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Fresh Paint Sapphire 23 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Heir Apparent 5 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Heir Apparent Jade 5 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Heir Apparent Ruby 5 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Court Kings Basketball Heir Apparent Sapphire 5 Rodions Kurucs 2018 Absolute Basketball Glass 1 Anthony Davis 2018 Chronicles Basketball Gold Standard Rookie Jersey Autographs 20 Grayson Allen 2018 Chronicles Basketball Gold Standard Rookie Jersey Autographs 25 Kevin Knox 2018 Chronicles Basketball Gold Standard Rookie Jersey Autographs Prime 25 Kevin Knox 2018 Chronicles Basketball Rookie Ascent 28 Kevin Knox 2018 Chronicles Basketball Rookie Ascent 21 Landry Shamet 2018 Chronicles Basketball Rookie Ascent Gold 28 Kevin Knox 2018 Chronicles Basketball Rookie Ascent Gold 21 Landry Shamet -

The Chuck Daly Collection Goes up for Auction

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Terry Melia – 949-831-3700, [email protected] THE CHUCK DALY COLLECTION GOES UP FOR AUCTION STARTING ON AUGUST 5TH The Late Pistons’ head coach earned two NBA titles and guided the ’92 ‘Dream Team’ to Olympic gold Laguna Niguel, Calif. (July 23, 2015) – The late Chuck Daly was known for his ability to create harmony out of diverse personalities at all levels of basketball. The former NBA head coach could bridge differences between superstar Dream Teamers like Michael Jordan and Charles Barkley as well as Pistons teammates as unalike as Dennis Rodman and Joe Dumars. Daly once said: “It’s a players’ league. They allow you to coach them or they don’t. Once they stop allowing you to coach, you’re on your way out.” Next month, starting on Wed., August 5, dozens of pieces from Daly’s personal memorabilia collection go on the auction block at www.scpauctions.com. The company’s Mid-Summer Classic online auction concludes on Sat., August 22. The online preview unveils next Wed., July 29. Topping the list of coveted items from the Daly Collection is an important 1992 U.S. Men’s Basketball “Dream Team” signed and painted game-used basketball from the team’s historic Olympic gold medal winning game against Croatia. A total of 12 signatures (11 players plus Daly) can be found on the prized basketball including Michael Jordan, Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, Clyde Drexler, Karl Malone and Charles Barkley. Other noteworthy items from the Daly Collection include his hand-written notes scribbled during his first meeting with the Dream Team members in June of 1992, as well as an original type- written and signed letter from Michael Jordan to the coach in November of ‘94. -

25Th Anniversary of American Century Championship Tees Off at Tahoe South, July 15--20

25TH ANNIVERSARY OF AMERICAN CENTURY CHAMPIONSHIP TEES OFF AT TAHOE SOUTH, JULY 15--20 Annika, Charles Barkley, Steph Curry, Aaron Rodgers headline field of 86 stars July 11, 2014 (South Lake Tahoe Calif./Nev.) – Star sightings are in the cards and on the course next week for the 25th anniversary of the American Century Championship at Edgewood Tahoe Golf Course, July 15-20 (www.TahoeCelebrityGolf.com). The No. 1 celebrity sports event in the USA is expecting record attendance with the addition of Annika Sorenstam to the field of 86 sports and entertainment stars, a forecast of perfect weather and the area’s 24-hour lifestyle. Fans will find Hall of Famers from the NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL, along with entertainment personalities competing for $125,000 of the $600,000 purse. All eyes, however, will be on Annika Sorenstam, the LPGA legend who if based on pre- tournament wagering is the early favorite. Harrah’s and Harveys Race & Sports Book originally installed her as the 2 to 1 favorite, but now lists the 89 time tournament winner -- including 10 major championships, at 5 to 4. Other marquee names include Charles Barkley, Steph Curry and Aaron Rodgers, NFL Hall of Famers Steve Young, Jerry Rice and John Elway; Larry the Cable Guy, current Kansas City Chiefs and former 49ers quarterback Alex Smith; former major league All-Star Chipper Jones; actor-comedian Kevin Nealon; NASCAR drivers Denny Hamlin and Michael Waltrip; and Bush Center Wounded Warrior Champion Chad Pfeifer. Elway, along with Jack Wagner, Mike Eruzione, and Jim McMahon have played all 25 years First-timers include Geno Auriemma, head coach of the 9-time national women’s champion basketball team at the University of Connecticut; Roger Clemens, 7-time Cy Young Award winner; Alan Thicke of Unusually Thicke and Growing Pains fame.