The President and Immigration Law Redux Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Supreme Court of the United States

Nos. 18-587, 18-588, and 18-589 In the Supreme Court of the United States DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT JOINT APPENDIX (VOLUME 2) NOEL J. FRANCISCO ROBERT ALLEN LONG, JR. Covington & Burling, LLP Solicitor General Department of Justice One CityCenter Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 850 Tenth St., N.W. [email protected] Washington, D.C. 20001 (202) 514-2217 [email protected] (202) 662-5612 Counsel of Record Counsel of Record for Petitioners for Respondents Regents of the University of California and Janet Napolitano (No. 18-587) PETITIONS FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED: NOV. 5, 2018 CERTIORARI GRANTED: JUNE 28, 2019 Additional Captions and Counsel Listed on Inside Cover DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI BEFORE JUDGMENT TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT KEVIN K. MCALEENAN, ACTING SECRETARY OF HOMELAND SECURITY, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. MARTIN JONATHAN BATALLA VIDAL, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI BEFORE JUDGMENT TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT Additional Counsel For Respondents THEODORE J. BOUTROUS, JR. MICHAEL JAMES MONGAN Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Solicitor General LLP California Department of 333 South Grand Ave. Justice Los Angeles, CA. 90071 455 Golden Gate Ave., Suite 11000 [email protected] San Francisco, CA. 94102 (213) 229-7804 [email protected] (415) 510-3920 Counsel of Record Counsel of Record for Respondents for Respondents Dulce Garcia, Miriam States of California, Maine, Gonzalez Avila, Saul Maryland, and Minnesota Jimenez Suarez, Viridiana (No. -

Old Japan Redux 3

Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG February 2017 The cover painting is a section from 弱竹物語, National Diet Library. Old Japan Redux 3 Edited by X. Jie YANG, February 2017 Content Poem and Stories The Origins of Japan ……………………………………………… April Grace Petrascu 2 Journal of an Unnamed Samurai ………………………………… Myles Kristalovich 5 Holdout at Yoshino ……………………………………………………… Zachary Adrian 8 Memoirs of Ieyasu ……………………………………………………………… Selena Yu 12 Sword Tales ………………………………………………………………… Adam Cohen 15 Comics Creation of Japan …………………………………………………………… Karla Montilla 19 Yoshitsune & Benkei ………………………………………………………… Alicia Phan 34 The Story of Ashikaga Couple, others …………………… Qianhua Chen, Rui Yan 44 This is a collection of poem, stories and manga comics from the final reports submitted to Japanese Civilization, fall 2016. Please enjoy the young creativity and imagination! P a g e | 2 The Origins of Japan The Mythical History April Grace Petrascu At the beginning Izanagi and Izanami descended The universe was chaos Upon these islands The heavens and earth And began to wander them Just existed side by side Separately, the first time Like a yolk inside an egg When they met again, When heaven rose up Izanami called to him: The kami began to form “How lovely to see Four pairs of beings A man such as yourself here!” After two of genesis The first-time speech was ever used. Creating the shape of earth The male god, upset Izanagi, male That the first use of the tongue Izanami, the female Was used carelessly, Kami divided He once again circled the land By their gender, the only In an attempt to cool down Kami pair to be split so Once they met again, Both of these two gods Izanagi called to her: Emerged from heaven wanting “How lovely to see To build their own thing A woman like yourself here!” Upon the surface of earth The first time their love was matched. -

Military Retirement Fund Audited Financial Report

Fiscal Year 2020 Military Retirement Fund Audited Financial Report November 9, 2020 Table of Contents Management’s Discussion and Analysis ..............................................................................................................1 REPORTING ENTITY ....................................................................................................................................... 1 THE FUND ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 General Benefit Information ........................................................................................................................... 2 Non-Disability Retirement from Active Service ............................................................................................ 3 Disability Retirement ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Reserve Retirement ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Survivor Benefits ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Temporary Early Retirement Authority (TERA) ............................................................................................ 9 Cost-of-Living Increase ................................................................................................................................. -

The Importance of Land Warfare: This Kind of War Redux

No. 117 JANUARY 2018 The Importance of Land Warfare: This Kind of War Redux David E. Johnson The Importance of Land Warfare: This Kind of War Redux by David E. Johnson The Institute of Land Warfare ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY AN INSTITUTE OF LAND WARFARE PAPER The purpose of the Institute of Land Warfare is to extend the educational work of AUSA by sponsoring scholarly publications, to include books, monographs and essays on key defense issues, as well as workshops and symposia. A work selected for publication as a Land Warfare Paper represents research by the author which, in the opinion of the Institute’s editorial board, will contribute to a better understanding of a particular defense or national security issue. Publication as an Institute of Land Warfare Paper does not indicate that the Association of the United States Army agrees with everything in the paper but does suggest that the Association believes the paper will stimulate the thinking of AUSA members and others concerned about important defense issues. LAND WARFARE PAPER No. 117, January 2018 The Importance of Land Warfare: This Kind of War Redux by David E. Johnson David Johnson is a principal researcher at the RAND Corporation. His work focuses on strategy, military doctrine, history, innovation, civil-military relations and professional military education. From June 2012 to July 2014 he established and led the Chief of Staff of the Army Strategic Studies Group for General Raymond Odierno. He is an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and an adjunct scholar at the Modern War Institute at West Point. -

Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2012 Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Amy, "Threnody" (2012). English Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/21 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threnody By Amy Fitzgerald English Department Honors Project, May 2012 Advisor: Peter Bognanni 1 Glossary of Words, Terms, and Institutions Commissie voor Oorlogspleegkinderen : Commission for War Foster Children; formed after World War II to relocate war orphans in the Netherlands, most of whom were Jewish (Dutch) Crèche : nursery (French origin) Fraulein : Miss (German) Hervormde Kweekschool : Reformed (religion) teacher’s training college Hollandsche Shouwberg : Dutch Theater Huppah : Jewish wedding canopy Kaddish : multipurpose Jewish prayer with several versions, including the Mourners’ Kaddish KP (full name Knokploeg): Assault Group, a Dutch resistance organization LO (full name Landelijke Organasatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers): National Organization -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

A Governor's Guide to Homeland Security

A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION (NGA), founded in 1908, is the instrument through which the nation’s governors collectively influence the development and implementation of national policy and apply creative leadership to state issues. Its members are the governors of the 50 states, three territories and two commonwealths. The NGA Center for Best Practices is the nation’s only dedicated consulting firm for governors and their key policy staff. The NGA Center’s mission is to develop and implement innovative solutions to public policy challenges. Through the staff of the NGA Center, governors and their policy advisors can: • Quickly learn about what works, what doesn’t and what lessons can be learned from other governors grappling with the same problems; • Obtain specialized assistance in designing and implementing new programs or improving the effectiveness of current programs; • Receive up-to-date, comprehensive information about what is happening in other state capitals and in Washington, D.C., so governors are aware of cutting-edge policies; and • Learn about emerging national trends and their implications for states, so governors can prepare to meet future demands. For more information about NGA and the Center for Best Practices, please visit www.nga.org. A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY NGA Center for Best Practices Homeland Security & Public Safety Division FEBRUARY 2019 Acknowledgements A Governor’s Guide to Homeland Security was produced by the Homeland Security & Public Safety Division of the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) including Maggie Brunner, Reza Zomorrodian, David Forscey, Michael Garcia, Mary Catherine Ott, and Jeff McLeod. -

Countering False Information on Social Media in Disasters and Emergencies, March 2018

Countering False Information on Social Media in Disasters and Emergencies Social Media Working Group for Emergency Services and Disaster Management March 2018 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 2 Motivations .................................................................................................................................... 4 Problem ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Causes and Spread ................................................................................................................... 6 Incorrect Information .............................................................................................................. 6 Insufficient Information ........................................................................................................... 7 Opportunistic Disinformation .................................................................................................. 8 Outdated Information ............................................................................................................. 8 Case Studies ............................................................................................................................... 10 -

Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025

TEXAS HOMELAND SECURITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2021-2025 LETTER FROM THE GOVERNOR Fellow Texans: Over the past five years, we have experienced a wide range of homeland security threats and hazards, from a global pandemic that threatens Texans’ health and economic well-being to the devastation of Hurricane Harvey and other natural disasters to the tragic mass shootings that claimed innocent lives in Sutherland Springs, Santa Fe, El Paso, and Midland-Odessa. We also recall the multi-site bombing campaign in Austin, the cybersecurity attack on over 20 local agencies, a border security crisis that overwhelmed federal capabilities, actual and threatened violence in our cities, and countless other incidents that tested the capabilities of our first responders and the resilience of our communities. In addition, Texas continues to see significant threats from international cartels, gangs, domestic terrorists, and cyber criminals. In this environment, it is essential that we actively assess and manage risks and work together as a team, with state and local governments, the private sector, and individuals, to enhance our preparedness and protect our communities. The Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025 lays out Texas’ long-term vision to prevent and respond to attacks and disasters. It will serve as a guide in building, sustaining, and employing a wide variety of homeland security capabilities. As we build upon the state’s successes in implementing our homeland security strategy, we must be prepared to make adjustments based on changes in the threat landscape. By fostering a continuous process of learning and improving, we can work together to ensure that Texas is employing the most effective and innovative tactics to keep our communities safe. -

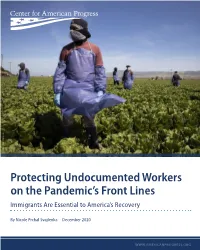

Protecting Undocumented Workers on the Pandemic's Front Lines

GETTY STIRTON IMAGES/BRENT Protecting Undocumented Workers on the Pandemic’s Front Lines Immigrants Are Essential to America’s Recovery By Nicole Prchal Svajlenka December 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 3 Undocumented immigrants in the U.S. workforce 10 Undocumented immigrants on the front lines of the pandemic response 13 Positioning the United States for recovery means including undocumented immigrants 17 Conclusion 18 About the author 19 Methodological appendix 29 Endnotes Introduction and summary Across the United States, Americans continue to face the harsh reality of life amid a global pandemic and the ensuing economic fallout. More than 7 million people have lost their jobs since February 2020.1 Americans are worrying about whether and when their children can safely return to school; they have watched their favor- ite restaurants close, first temporarily and then permanently; and they have been forced to spend holidays without their families and loved ones. And with cases continuing to rise, this public health crisis is far from over. Among those Americans bearing the brunt of the pandemic and its economic fall- out are 10.4 million undocumented immigrants.2 At the same time, over the past nine months, millions of these immigrants have worked alongside their neighbors to keep the country functioning and safe. They have worked as doctors and nurses caring for loved ones and fighting this pandemic, but these unique times have also highlighted their crucial work as agricultural workers harvesting Americans’ food; clerks stocking grocery shelves; and delivery drivers bringing food to the safety of people’s homes. -

CHALLENGING ETHNIC PROFILING in EUROPE a Guide for Campaigners and Organizers

CHALLENGING ETHNIC PROFILING IN EUROPE A Guide for Campaigners and Organizers — 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This guide was written by Zsolt Bobis, Rebekah Delsol, Maryam H’madoun, Lanna Hollo, A tremendous appreciation is also expressed for the countless and often invisible yet critical Susheela Math, and Rachel Neild of the Fair and Effective Policing team at the Open Society efforts and contributions of other OSF colleagues and the many local actors involved in Justice Initiative (OSJI). Open Society Foundations Communications Officer Brooke Havlik litigation, mobilizing and organizing, and advocacy and campaigning against ethnic profiling made significant contributions, and further assistance was provided by OSF Aryeh Neier in different EU countries. The work described here would not have been possible without Fellow Michèle Eken. them, and reflects the collective efforts of all. Examples and case studies were included from key organizations tackling ethnic profiling and The report was reviewed and edited by David Berry, Erika Dailey, James A. Goldston, and police abuse in Europe and the US, including StopWatch, Controle Alt Delete, Amnesty Robert O. Varenik. International Netherlands, the French platform En finir avec les contrôles au faciès, Eclore, Maison Communautaire pour un Développement Solidaire (MCDS, Paris 12), WeSignIt, Plataforma por la Gestión Policial de la Diversidad, Rights International Spain, SOS Racisme Catalunya, Hungarian Helsinki Committee, Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU), the Belgian platform Stop Ethnic Profiling,