Handling of Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS Veterinarians Are the Doctors Specializing in the Health of Animals

SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS Veterinarians are the doctors specializing in the health of animals. They do the necessary surgical operations and care for the well-being of the animal creatures. The very basic thing they need in a certain operation and care are the veterinary instruments. This will serve as the main allay of every veterinarian in providing care. (1) What are surgical instruments? Surgical instruments are essentially gadgets planned in an uncommon manner to perform particular capacities amid a surgical operation to improve viability and accomplishment of the surgery. (1) 4 Basic types of surgical instruments Surgical instruments are specially designed tools that assist health care professionals car- ry out specific actions during an operation. Most instruments crafted from the early 19th century on are made from durable stainless steel. Some are designed for general use, and others for spe- cific procedures. There are many surgical instruments available for almost any specialization in medicine. There are precision instruments used in microsurgery, ophthalmology and otology. Most surgical instruments can be classified into these 4 basic types: Cutting and Dissecting – these instruments usually have sharp edges or tips to cut through skin, tissue and suture material. Surgeons need to cut and dissect tissue to explore irregular growths and to remove dangerous or damaged tissue. These instruments have single or double razor- sharp edges or blades. Nurses need to be very careful to avoid injuries, and regularly inspect these instruments before using, for re-sharpening or replacement. 11 Iris Scissors 2016 – 1 – LV01-KA202 – 022652 This project is funded by the European Union Clamping and Occluding – are used in many surgical procedures for compressing blood vessels or hollow organs, to prevent their contents from leaking. -

The Introductory Guide/Basic Course #1 Chapter I About Sklar for 123 Years, Sklar Has Set the Standard for Surgical Instrumentation

Surgical Instruments: The Introductory Guide/Basic Course #1 Chapter I About Sklar For 123 years, Sklar has set the standard for surgical instrumentation. In 1892, German born instrument maker John Sklar, founded the company to fill a need for American made surgical instruments and the rest is history. Sklar rose to prominence during World Wars I and II and was awarded the principal contract as the surgical instrument provider for the United States military. This contract established Sklar as the industry leader and placed it on the forefront of the surgical marketplace, where it went on to receive Certificates of Merit and Achievement from the U.S. Navy and six Army Navy “E” Production Awards. During the 1930s, Sklar’s research department helped to develop a stainless steel alloy especially suited to the manufacture of surgical instruments. The company’s investment in research was justified long-term; most surgical instruments are still made of long-lasting, rust resistant, stainless steel. Today, Sklar is headquartered in West Chester, Pennsylvania where it remains the authority on the manufacture of high quality surgical instruments to medical professionals in 75 countries worldwide. Throughout its history, Sklar has collaborated with leading surgeons and medical facilities to develop thousands of unique surgical instrument patterns. In recent years, Sklar has expanded its product line to include more than 19,000 precision crafted, stainless steel instruments: the largest offering of surgical instruments in the world. Specialty practices include: OB/GYN, Orthopedic, ENT, Cardiovascular, Endoscopic, Dermatology, Podiatry, Veterinary, Dental, etc. The prevention and reduction of healthcare associated infection (HAI) is a top priority in medical facilities today. -

The World of SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS

Textbook Preview The World of SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS The Definitive Inspection Textbook 501 full color pages 1,198 high resolution photos Glossy, hard cover Lay flat design by RICK SCHULTZ SCISSORS Frequently Asked Questions Q: Do all scissors go dull? A: Yes. Every scissor goes dull no matter what size, specialty, manufacturer, or design. Q: Does sterilization dull a scissor? A: Generally, no. However, when old autoclaves produce dirty steam, the scissor blade edges can become stained, which can cause the scissor not to cut. Q: Can all scissors be resharpened? A: Yes. Every scissor can be resharpened. Make sure the repair vendor is properly trained, especially on SuperCut scissors (black-handled). Q: How often should scissors be tested? A: Scissors should be tested 1 to 2 times per week. The proactive approach is picking 2 days per week as scissor testing days. Using an instrument tracking system will allow the facility to track sharpening frequency. Eventually, a large percentage of scissors will be sharp. Q: Is the scissor testing standard red and yellow scissor test material? A: Yes. The industry standard is to use red scissor test material for scissors longer than 41⁄2" in overall length and yellow scissor test material for scissors that measure 41⁄2" and shorter. Yellow scissor test material is used on 41⁄2" scissors. Q: Do all repair technicians know how to sharpen scissors? A: No. Experience and proper training is key, and many times repair technicians are learning on your expensive instrument inventory. The hospital should verify how many months of training/employment the repair technician has. -

The Basic Surgery Kit

GLOBAL EXCLUSIVE > SURGERY > PEER REVIEWED The Basic Surgery Kit Jan Janovec, MVDr, MRCVS VRCC Veterinary Referrals Laurent Findji, DMV, MS, MRCVS, DECVS Fitzpatrick Referrals Considering the virtually limitless range of surgical instruments, it can be difficult to assemble a cost-effective basic surgery kit. Some instruments may misleadingly appear multipurpose, but their misuse may damage them, leading to unnecessary replacement costs or, worse, intraoperative accidents putting the patient’s safety at risk. Many instru- ments are available in different qualities and materials (eg, tungsten carbide instruments— more expensive but much more resistant to wear and corrosion than stainless steel) and Minimal Basic Surgery Kit varied sizes to match the purpose of their use as well as the size of the surgeon’s hand. n 1 instrument case Cutting Instruments n 1 scalpel handle Scalpel n 1 pair Mayo scissors The scalpel is an indispensible item in a surgical kit designed to make sharp incisions. Scalpel incision is the least traumatic way of dissection, but provides no hemostasis. n 1 pair Metzenbaum scissors Scalpel handles come in various sizes, each accommodating a range of disposable n 1 pair suture scissors blades (Figure 1). Entirely disposable scalpels are also available. n 1 pair Mayo-Hegar needle holder Scissors n 1 pair Brown-Adson tissue forceps Scissors are used for cutting, albeit with some crushing effect, and for blunt dissection. n 1 pair DeBakey tissue forceps Fine scissors, such as Metzenbaum scissors (Figure 2), should be reserved for cutting n 4 pairs mosquito hemostatic forceps and dissecting delicate tissues. Sturdier scissors, such as Mayo or suture scissors, are designed for use on denser tissues (eg, fascia) or inanimate objects (eg, sutures, drapes). -

Vitreo Retina Surgical Instruments Catalog 2014

BR554-14 General Information Vitreo Retina Instruments: Trocar Set WARRANTY/GUARANTEE All ASICO ophthalmic instruments are unconditionally guaranteed for life against manufacturing defects in material and workmanship when used for their intended surgical purpose and cared for in accordance with recommended procedure. In the event any ASICO instrument should fail as a result of a manufacturing defect in material or workmanship, it will be replaced or repaired at no charge. TERMS OF PAYMENT Invoices are payable on receipt. If payment is received after the initial 30-day period, a finance charge of 1.5% for an annual rate of 18% will be charged. SHIPPING Shipments of surgical instruments are made via FedEx Second Day Air. Shipment can also be made via UPS or DHL upon customer request, with a valid shipping account number for requested shipping vendor. If customer uses their shipping account number a handling fee will still apply to the order. ORDERS Orders can be placed through our toll-free customer service line, 1-800-628-2879, by fax, by calling 1-630-986-8032 or by emailing [email protected]. PRICES Prices are in US Dollars and are subject to change without notice. RETURN POLICY All products returned to ASICO must be accompanied by a return authorization number. This number can be obtained by contacting ASICO by phone or email. Merchandise should be carefully packaged, shipped prepaid, insured and mailed to the Westmont office. Each shipment must be accompanied by a document showing the full name and address of a sender, list of items, and the reason for return. -

Laparoscopic Instruments

Laparoscopic Instruments Product Catalog Aesculap Laparoscopy 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4-5 Ligation 101-107 Advanced Energy 7-9 DS Clips 102-105 Caiman® Vessel Sealers 8-9 Challenger™ Ti-P 106-107 Monopolar Instruments 11-69 Access & Closure 109-123 Advanced Energy Single Use 12-15 Access Instruments 110 Reposable 16-17 Insufflation 111 Reusable 18-73 Rigid Trocars 112-113 3.5 mm mini 20-23 3.5 mm 113 Scissors 24-29 5 mm 114 Dissecting Forceps 30-35 10 mm 115 Monopolar Instruments Grasping Forceps 36-57 12 mm 116 Biopsy Forceps 58-61 HASSON 117 Spare parts 3.5 mm, 5 mm & 10 mm 62-63 Accessories & Spare Parts 118 Assembly/Disassembly 64-66 Additional Instruments 119 Electrodes 68-69 Flexible Trocars 120-121 Bipolar Instruments Bipolar Instruments 70-74 7 mm & 13 mm 120 Single use 70-71 Accessories & Spare Parts 121 Reusable 72-74 Closure 122-123 Assembly/Disassembly 74 Instruments 123 Specialty Instruments 75-100 Endoscopes 125-127 Slide Lock Graspers 76 Specialty Instruments Endoscopes 126 Bulldog Clips 77 Light Cables 127 Video-Assisted Thorascopic Surgery (VATS) 78-89 Care & Storage 129-138 Advanced Urology 90-91 Services 139-143 Needle Holders & Suturing 92-93 Ligation Index 144-151 Retractors 94-95 Nathanson Retractors 96-97 Suction/Irrigation 98 Suction/Irrigation with Monopolar 99 Closure & Miscellaneous Instruments 100 Access Endoscopes Storage & Care 3 History Blending Old World Craftsmanship with Modern Technology Aesculap AG World Headquarters in Tuttlingen, Germany Our founding father: Aesculap Gottfried Jetter As the -

Forceps & Hemostats

Forceps & Hemostats Dumont Pages 63 – 72 See page 189 for alloy and additional information. Fine Pages 73 – 80 Moria Page 74 S&T Pages 75, 77 Standard Pages 81 – 91 Hemostats Pages 92 – 97 DUMONT® FORCEPS Dumont #5SF Dumont #5 Dumont #5 Dumont #5CO The finest tips ever Fine Tips Ceramic Coated These forceps have been produced by Dumont. Finished under magnification and These forceps are non-reflective. honed down to make this the polished on the inside, the tips The scratch and corrosion resistant lightest and most precise close flat to 3 mm and are less likely coating guarantees durability. Dumont forceps available. to open under excess pressure. FORCEPS For information on Dumont alloys and tip styles, see page 189. Super fine tip Biology tip Biology tip Biology tip 0.025 x 0.005 mm 0.05 x 0.01 mm 0.05 x 0.01 mm 0.05 x 0.01 mm Inox Inox Ceramic coated inox Dumostar 11 cm 11 cm 11 cm 11 cm No. 11252-00 No. 11254-20 No. 11252-50 No. 11295-20 63 FINESCIENCE.COM · MOST ITEMS SHOWN ACTUAL SIZE DUMONT® FORCEPS Dumont Micro-Blunted, Atraumatic Tipped Forceps The sides of these forceps are distinctively ribbed to provide a better holding surface for maximum control of the instrument. The shanks are arched toward each other to transmit more holding strength to the points. The smooth inside surfaces at the tips will close flat to 5 mm with gentle pressure, increasing the total holding area considerably. The microscopically matched tips are gently blunted to prevent tissue puncture and are recommended as micro needle holders. -

Directions for Use Euro-Med®

Directions for Use Euro-Med® LEEP Non-Conductive Rose-Coated Instruments Non-Sterile: Sterilize Before Use. (Non-conductive, fully autoclavable LEEP instruments offer a variety of styles to facilitate cervical tissue excision and removal) Distributed by: 37838 • Rev. B • 11/13 Available Models (LEEP Coated): Standard Specula Retractors Graves Jackson F205 Medium F235 Medium F200 Large F234 Large Pederson Truview F223 Small F317 Lateral Wall F221 Medium F220 Large Cer-View™ Collin F410 Lateral Wall - Medium F420 Lateral Wall - Large F225 Medium F227 Large F400 Lateral Vaginal Retractor Auvard F230 Medium F232 Large Forceps ™ Snowman F700 LEEP Tissue Forceps F107 Graves Blade F920 LEEP Ring Forceps F117 Pederson Blade F925 LEEP Campion Forceps F127 Set: One of each: Graves & Pederson Vu-More™ Hooks Graves Blade F800 LEEP Iris Hook (263 mm) F250 Mini F802 LEEP 2-Prong Hook (260 mm) F217 Medium F803 LEEP 3-Prong Hook (260 mm) F215 Large F810 LEEP Straight Hook (250 mm) F812 LEEP Left Angle Hook Vu-Max™ F813 LEEP Right Angle Hook Graves Blade F218 Medium F219 Large Tenaculums F805 LEEP Emmett Tenaculum Pederson Blade F900 LEEP Single Tooth Tenaculum F222 Medium F224 Large Open-Sided – Graves Rulers F210 Open Sided F600 LEEP Depth Ruler (240 mm) F610 LEEP Width Ruler (210 mm) Endocervical F510 Medium F500 Large 37838 • Rev. B • 11/13 Euro-Med® LEEP Instruments Specula, Retractors, Forceps, Hooks, Tenaculums, Rulers Directions for Use DESCRIPTION Euro-Med® LEEP instruments allow use in almost any situation. Rose-coated LEEP electrosurgical instruments are used for general office or operating room use. All of the rose-coated LEEP instruments are non-conductive and can be sterilized in an autoclave. -

LAPAROSCOPIC SUTURING SYSTEM with the SZABO-BERCI NEEDLE DRIVER SET Including an Illustrated Slip Knot Demonstration

® LAPAROSCOPIC SUTURING SYSTEM WITH THE SZABO-BERCI NEEDLE DRIVER SET including an Illustrated Slip Knot Demonstration Zoltán SZABÓ LAPAROSCOPIC SUTURING SYSTEM WITH THE SZABO-BERCI NEEDLE DRIVER SET including an Illustrated Slip Knot Demonstration Zoltán SZABO, Ph.D., F.I.C.S San Francisco, California, U.S.A. 4 Laparoscopic Suturing System with the SZABO-BERCI Needle Driver Set Clinical cases: Laparoscopic Suturing System with the Barry N. Gardiner, M.D. SZABO-BERCI Needle Driver Set San Ramon, California, U.S.A. including an Illustrated Slip Knot Demonstration and Zoltán Szabó, Ph.D., F.I.C.S Steven A. Stanten, M.D. San Francisco, California, U.S.A Oakland, California, U.S.A. Correspondence address of the author: Zoltán Szabó, Ph.D., F.I.C.S., M.O.E.T. Institute Microsurgery & Operative Endoscopy Training Director: Zoltán Szabó 153, States Street San Francisco, CA 94114, U.S.A. Phone: 001 (415) 626-34 00 Fax: 001 (415) 626-34 44 E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. 1st edition 1993 © 2015 GmbH P.O. Box, 78503 Tuttlingen, Germany Important notes: Phone: +49 (0) 74 61/1 45 90 Medical knowledge is ever changing. As new research and clinical Fax: +49 (0) 74 61/708-529 experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and therapy E-Mail: [email protected] may be required. The authors and editors of the material herein have consulted sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide No part of this publication may be translated, reprinted information that is complete and in accord with the standards or reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, accept ed at the time of publication. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,652,450 B2 Neisz Et Al

USOO665245OB2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,652,450 B2 Neisz et al. (45) Date of Patent: Nov. 25, 2003 (54) IMPLANTABLE ARTICLE AND METHOD FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS FOR TREATING URINARY INCONTINENCE USING MEANS FOR REPOSITONING THE RE 5, c. 33. IMPLANTABLE ARTICLE EP O470308 A1 2/1992 EP O 650 703 A1 6/1994 (75) Inventors: Johann J. Neisz, Coon Rapids, MN (US); John W. Westrum, Jr., Prior (List continued on next page.) Lake, MN (US); Christopher H. Porter, Woodinville, WA (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS Beck, Peter R. et al., Treatment of Urinary Stress Inconti (73) ASSignee: η Mystems Inc., nence With Anterior Colporrhaphy, Obstetrics and Gynecol InnelOn Ka, ogy, vol 59 (No. 3), pp. 269-274 (Mar. 1982). (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Es ES, MD, A Modified Play t atent is extended or adjusted under 35 patient Bladder Neck Suspension System, Journal of Urol C. 154(b) by 0 days ogy, vol. 152, pp. 23.16-2320 (Dec. 1994). a -- y yS. Benderev, Theodore V., MD, Anchor Fixation and Other Modifications of Endoscopic Bladder Neck Suspension, (21) Appl. No.: 09/917,562 Urology, vol 40, No. 5, pp. 409–418 (Nov. 1992). (22) Filed: Jul. 27, 2001 Das, Sakti et al., Laparoscopic Colpo-Suspension, The O O Journal of Urology, vol. 154, pp. 1119-1121 (Sep. 1995). (65) Prior Publication Data Gilja, Ivan et al., A Modified Raz Bladder Neck Suspension US 2002/0107430 A1 Aug. 8, 2002 Operation (Transvaginal Burch), The Journal of Urology, vol. 153, pp. 1455–1457 (May 1995). -

STILLE Surgical Instruments

Selected Models STILLE Surgical Instruments Quality tools behind the talent Surgical Perfection ”The world’s best instruments, for the world’s best surgeons” STILLE Surgical Instruments For over 175 years, we have developed and manufactured the best surgical In this catalogue you will find a wide selection of instruments, Including the instruments for the world’s most demanding surgeons. We would like to original supercut scissor developed in 1984 and our new Diamond supercut extend a sincere thank you to all our current customers and welcome our design. Quality goes into our STILLE forceps, needle holders, clamps, rongeurs, future customers to experience the STILLE difference. In this catalog we curettes and retractors, as well as, a fine selection of stainless and titanium present a selection of STILLE original surgical instruments. micro instruments. Common to all of our instruments is that they are smooth and consistently perform to your expectations. Our outstanding balance, Precision, durability and feel are characteristic qualities of all STILLE solid design and ergonomics provides the surgeon with a reliable instrument instruments. The majority are handcrafted by our highly skilled artisans in throughout long and complex procedures. Eskilstuna, Sweden. Our instrument manufacturing process from melting steel rods to finished product is a long one, involving multiple stages of We at STILLE are proud to have developed the world’s first double-action development. Our method of crafting STILLE instruments involves only bone ronguer. We also developed the world’s first osteotome with the classic the highest-grade steel, which provides a unique feel and reliability to the 8-sided handle. -

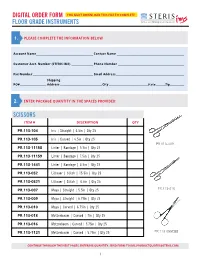

Floor Grade Instruments

DIGITAL ORDER FORM YOU MUST DOWNLOAD THIS FILE TO COMPLETE FLOOR GRADE INSTRUMENTS 1. PLEASE COMPLETE THE INFORMATION BELOW Account Name__________________________________________________ Contact Name ___________________________________________________________ Customer Acct. Number (STERIS IMS) ___________________ Phone Number __________________________________________________________ Fax Number _____________________________________________________ Email Address ____________________________________________________________ Shipping PO# _______________________ Address _____________________________________City __________________________________State ________ Zip_____________ 2. ENTER PACKAGE QUANTITY IN THE SPACES PROVIDED: SCISSORS ITEM # DESCRIPTION QTY PR.113-104 Iris | Straight | 4.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-105 Iris | Curved | 4.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-009 PR.113-11158 Lister | Bandage | 5.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-11159 Lister | Bandage | 7.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-1441 Lister | Bandage | 4.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-052 Littauer | Stitch | 15.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-0521 Littauer | Stitch | 4.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-007 Mayo | Straight | 5.5in | Qty 25 PR.113-010 PR.113-009 Mayo | Straight | 6.75in | Qty 25 PR.113-010 Mayo | Curved | 6.75in | Qty 25 PR.113-018 Metzenbaum | Curved | 7in | Qty 25 PR.113-016 Metzenbaum | Curved | 5.75in | Qty 25 PR.113-1121 Metzenbaum | Curved | 5.75in | Qty 25 PR.113-055CBB CONTINUE THROUGH THE NEXT PAGES, ENTERING QUANTITY. SEND FORM TO [email protected]. 1 SCISSORS ITEM # DESCRIPTION QTY PR.113-0063 Voper | Blunt | Straight