Putting a Check on Police Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Rights Complaint

Case: 1:19-cv-04082 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/18/19 Page 1 of 28 PageID #:1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION MARCEL BROWN, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) CITY OF CHICAGO; Chicago Police ) Detectives MICHAEL MANCUSO, ) Case No. 19-cv-4082 KEVIN McDONALD, GARRICK ) TURNER, RUBIN WEBER, STEVE ) CZABLEWSKI, and WILLIAM ) BURKE; COUNTY OF COOK, ) ILLINOIS; Assistant State’s Attorney ) MICHELLE SPIZZIRRI, ) ) Defendants. ) CIVIL RIGHTS COMPLAINT Plaintiff, MARCEL BROWN, by his undersigned attorneys, complains of Defendants, CITY OF CHICAGO; Chicago Police Detectives MICHAEL MANCUSO, KEVIN McDONALD, GARRICK TURNER, RUBIN WEBER, STEVE CZABLEWSKI, and WILLIAM BURKE; COUNTY OF COOK, ILLINOIS; and Assistant State’s Attorney MICHELLE SPIZZIRRI, as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. In 2011, Marcel Brown was convicted on an accountability theory of the murder of Paris Jackson in Amundsen Park in the City of Chicago on the night of August 30, 2008, a crime he did not commit. Arrested at the age of 18, he spent nearly a decade in prison before ultimately being exonerated and certified innocent. 2. Marcel Brown’s wrongful conviction was no accident. Determined to close a murder case, the Defendantsthe Defendant Officers and Defendant Assistant State’s Attorney Case: 1:19-cv-04082 Document #: 1 Filed: 06/18/19 Page 2 of 28 PageID #:2 Michelle Spizzirricoerced false and inculpatory statements from Plaintiff. The Defendant Officers also fabricated evidence and withheld exculpatory evidence from the trial prosecutor and from the defense that would have prevented Plaintiff’s conviction. 3. As a result of the Defendants’ misconduct, Marcel Brown was charged and wrongfully convicted, and sentenced to 35 years in prison. -

Submission to the Un Committee Against Torture List of Issues Prior to Reporting, 7 November-7 December 2016

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: SUBMISSION TO THE UN COMMITTEE AGAINST TORTURE LIST OF ISSUES PRIOR TO REPORTING, 7 NOVEMBER-7 DECEMBER 2016 Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non- commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Index: AMR 51/4387/2016 Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Original language: English Street Printed by Amnesty International, London WC1X 0DW, UK International Secretariat, UK a mnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. IMPUNITY FOR TORTURE 4 3. BLOCKING OF REMEDY 4 4. GUANTÁNAMO 4 5. US DETAINEE TRANSFERS IN IRAQ, SYRIA AND OTHER PLACES 5 6. TASERS 5 7. POLICE TORTURE 6 8. POLICE USE OF LETHAL FORCE 6 9. LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE SENTENCES FOR JUVENILE OFFENDERS 6 10. -

Name Street City State Zip Code 1 Academic Tutoring 2550 Corporate Place Suite C108,Adriana L

NAME STREET CITY STATE ZIP CODE 1 ACADEMIC TUTORING 2550 CORPORATE PLACE SUITE C108,ADRIANA L. FLORES MONTEREY PARK CA 91754 1 TO 1 TUTOR PO BOX 3428 PALOS VERDES CA 90274 1 WORLD GLOBES AND MAPS 1605 SOUTH JACKSON ST., SEATTLE WA 98144 1:1 ONLINE TUTORING SERVICES 37303 CAROUSEL CIR, PALMDALE CA 93552 1060 TECHNOLOGIES 1406 77TH STREET, DARIEN IL 60561 10-S TENNIS SUPPLY 1400 NW 13TH AVE, POMPANO BEACH FL 33069 1st AYD CORP P.O. BOX 5298, ELGIN IL 60121-5298 1ST IN PADLOCKS 100 FACTORY ST,SECTION E 1 3RD FLOOR NASHUA NH 3060 1STOP CLARINET & SAX SHOP 11186 SPRING HILL DRIVE,UNIT #325 SPRING HILL FL 34609 24 HOUR TUTORING LLC 2637 E ATLANTIC BLVD #20686, POMPANO BEACH FL 33062 24/7 ONLINE EDUCATION PO BOX 10431, CANOGA PARK CA 91309 2ND WIND EXERCISE, INC. 4412 A/B EAST NEW YORK ST., AURORA IL 60504 3M CENTER 2807 PAYSPHERE CIR, CHICAGO IL 60674-0000 4IMPRINT 25303 NETWORK PLACE, CHICAGO IL 60673-1253 4MD MEDICAL SOLUTIONS 15 AMERICA AVE. SUITE 207, LAKEWOOD NJ 8701 4N6 FANATICS 253 WREN RIDGE DRIVE, EAGLE POINT 94 97524 5- MINUTE KIDS 3580 CRESTWOOD DRIVE, LAPEER MI 48446 59 AUTO REPAIR 24010 WEST RENWICK , PLANIFIELD IL 60544 8 to 18 MEDIA, INC. 1801 S. MEYERS RD. SUITE 300, OAKBROOK IL 60181 9TH PLANET, LLC 5865 NEAL AVENUE NORTH, NO 214, STILLWATER MN 55082 A & E HOME VIDEO P.O. BOX 18753,P.O. BOX 18753 NEWARK NJ 7191 A & E TELEVISION NETWORKS 235 EAST 45TH ST., NEW YORK NY 10017 A & M PHOTO WORLD 337 E. -

Application 1/2/2018

ig-oci OR IC! ILLINOIS HEALTH FACILITIES AND SERVICES REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR PERMIT- 02/2017 Edition ILLINOIS HEALTH FACILITIES AND SERVICES REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR PERMIT SECTION I. IDENTIFICATION, GENERAL INFORMATION, AND CERTIFICATION This Section must be completed for all projects. Facility/Project Identification Facility Name: Garfield Kidney Center Street Address: 408 — 418 North Homan Avenue City and Zip Code: Chicago, Illinois 60624 County: Cook Health Service Area: 6 Health Planning Area: 6 licant (refer to Part 1130.220 Exact Legal Name: DaVita Inc. Street Address: 2000 16m Street City and Zip Code: Denver, CO 80202 Name of Registered Agent: Illinois Corporation Service Company _f_tegistered Agent Street Address: 801 Adlai Stevenson Drive Registered Agent City and Zip Code: Springfield, Illinois 62703 Name of Chief Executive Officer: Kent Thiry CEO Street Address: 2000 16m Street CEO City and Zip Code: Denver, CO 80202 CEO Telephone Number: 303-405-2100 _Type of Ownership of Applicants • Non-profit Corporation • Partnership • For-profit Corporation O Governmental ▪ Limited Liability Company o Sole Proprietorship P Other o Corporations and limited liability companies must provide an Illinois certificate of good standing. o Partnerships must provide the name of the state in which they are organized and the name and address of each partner specifying whether each is a general or limited partner. APPEND DOCUMENTATION AS ATTACHMENT 1 IN NUMERIC SEQUENTIAL ORDER AFTER THE LAST PAGE OF THE APPLICATION FORM. ontact IPerson to receive ALL correspondence or in uiries Name: Tim Tincknell Title: Administrator Company Name: DaVita Inc. Address: 2484 North Elston Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60647 Telephone Number: 773-278-4403 E-mail Address: [email protected] Fax Number: 866-586-3214 Additional Contact Person who is also authorized to discuss the application for permit Name: Brent Habitz Title: Regional Operations Director Company Name: DaVita Inc. -

BTOP CCI Community Anchor Institutions Detail

BTOP CCI Community Anchor Institutions Detail Title: Illinois Broadband Opportunity Partnerhsip East Central Easy Grants ID: 4243 Facility Name Organization Address Line 1 City State Zip Facility Type A F Ames Elementary School Riverside SD 96 86 Southcote Rd Riverside IL 60546 School (K-12) Abraham Lincoln Elementary School Belleville SD 118 820 Royal Heights Rd Belleville IL 62223 School (K-12) Academy of Our Lady Academy of Our Lady 510 10Th St Waukegan IL 60085 School (K-12) Academy of Scholastic Achievement Academy of Scholastic Achievement 4651 W. Madison St Chicago IL 60644 School (K-12) Academy Of St. Benedict The African - Laflin Archdiocese of Chicago 6020 S. Laflin St Chicago IL 60636 School (K-12) Academy Of St. Benedict The African - Stewart Archdiocese of Chicago 6547 S. Stewart St Chicago IL 60621 School (K-12) Acorn Public Library District Acorn Public Library District 15624 S Central Avenue Oak Forest IL 60452 Library Adams Elementary School Lincoln Elementary Schools Dist 27 1311 Nicholson Rd Lincoln IL 62656 School (K-12) Addison Public Library Addison Public Library 4 Friendship Plaza Addison IL 60101 Library Adlai E Stevenson High School Adlai E Stevenson HSD 125 1 Stevenson Dr Lincolnshire IL 60069 School (K-12) Adler Planetarium And Astronomy Museum Adler Planetarium 1300 S Lake Shore Dr Chicago IL 60605 Other Community Support Organization Adler School Of Professional Psychology Adler School Of Professional Psychology 65 East Wacker Pl Chicago IL 60601 Other Institution of Higher Education Administration Center - Grundy County Of Grundy 1320 Union Street Morris IL 60450 Other Government Facility Aero Special Education Coop A E R O Special Education Coop 7600 S Mason Ave Burbank IL 60459 School (K-12) AGR - 801 E. -

CLASSACTIONREPORTER Wednesday, March 4, 2020, Vol. 22

C L A S S A C T I O N R E P O R T E R Wednesday, March 4, 2020, Vol. 22, No. 46 Headlines 3M CO: Bid to Transfer Firefighter's Class Suit Denied 3M CO: Consolidated Class Action Suit Ongoing in Michigan 3M CO: Discovery Ongoing in Parchment Resident's Class Suit 3M CO: King Class Action Remains Pending in Alabama ALC & CO. LLC: Website Not Accessible to Blind, Hedges Claims ALLAKOS INC: Rosen Law Firm Investigating Securities Claims ALTICE USA: Federman & Sherwood Files Action Over Data Breach AMERICAN FREIGHT: Eldridge Sues Over Unsolicited Text Message Ads ANIXTER INT'L: WESCO Merger Deal Lacks Info, Kent Claims AT&T MOBILITY: Pomales Suit Removed to District of Massachusetts AT&T SERVICES: Misclassifies Security Staff, Boteler Claims AUTOMILE PARENT: Coraccio Seeks OT Pay for Service Advisors B.C. LOTTERY: Class Action Suit Filed Over "Dangerous" Video Slots BALTIMORE LIFE: Griffin Sues over Unwanted Telemarketing Calls BECTON DICKINSON: Kabak Sues Over 12% Drop in Share Price BENELUX CORP: Wilder Sues over Overtime Pay, Illegal Kickbacks BEYOND MEAT: Robbins Geller Reminds of March 30 Plaintiff Deadline BJ SERVICES: Fails to Pay Overtime Wages, Shetter Claims BOTTLED BLONDE CHICAGO: Mitchell Balks at Collection of Biometrics CALYX ENERGY: Strong Seeks to Recover Unpaid Overtime Wages CAPITAL ACCOUNTS: Hawkins Sues over Unlawful Debt Collection CARDINAL AUTISM: Fields Seeks OT Pay for Behavioral Therapists CARDINAL LOGISTICS: Underpays Truck Drivers, Pavloff Claims CARE MATTERS: Fails to Pay Overtime Compensation, Campbell Claims CARLAY -

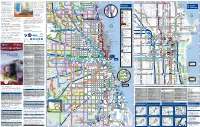

RTA Spanish System Map.Pdf

Stone Amtrak brinda servicios ferroviarios 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scott 13 14 Regional Transportation Sheridan r LaSalle desde Chicago Union Station a las er D 270 s C ent 421 Division Division Authority es 619 272 Edens Plaza Lake 213 sin ood u D 423 422 422 ciudades a través de Illinois y de los w B Clark/Division La Autoridad Regional de Transporte e Forest y Central 423 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie n r 422 800W 600W 200W 0 E/W P w GLENVIEW sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware Estados Unidos. Muchas de estas Preserve 620 C 421Union Pacific/North Line3rd 143 eeha l Forest Wilmette e La Baha’i Temple Elm F oll a D Green Bay 4th Green (RTA) se ocupa de la supervisión Antioch hasta v Glenview y Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T Glenview hasta Waukegan, Kenosha i Elm lo n r 210 Preserve 626 bard Linden Evanston sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware rutas, combinadas con autobuses de e Dewes b 421 146 financiera, del financiamiento y s Dea Mil Wilmette Foster 221 vice y Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) R Glenview Rd 94 Hi w 422 Thruway, están conectadas con 35 i i-State Chicago Cedar El Centro 221 Rand v r 270 au Emerson sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware Oakton T Central Hill de la planificación del transporte e National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena 70 147 r k Cook Co y Marine/Foster (5200N) ciudades de Illinois. Para obtener Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central 213 Courts k Central 213 Maple 93 Sheridan sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware regional para las tres operaciones de College S Presence 422 Gross 201 Hobbie 148 206 C Hooker y Marine/Irving -

2019 Inventory of Other Healthcare Services

Inventory of Health Care Facilities and Services and Need Determinations Illinois Health Facilities and Services Review Board 9/1/2019 Illinois Department of Public Health INVENTORY OF HEALTH CARE FACILITIES AND SERVICES AND NEED DETERMINATIONS 2019 OTHER HEALTH SERVICES Inventory of Health Care Facilities and Services and Need Determinations Illinois Health Facilities and Services Review Board 9/1/2019 Illinois Department of Public Health INVENTORY OF OTHER HEALTH SERVICES TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A. IN-CENTER HEMODIALYSIS A-1 – A-21 Section B. NON-HOSPITAL AMBULATORY SURGERY B-1 – B-13 Section C. ALTERNATIVE HEALTH CARE MODELS C-1 – C-9 Post-Surgical Recovery Care Center Models C-2 – C-4 Children’s Respite Care Models C-5 – C-7 Community-Based Residential Care Models C-8 – C-9 Inventory of Health Care Facilities and Services and Need Determinations Illinois Health Facilities and Services Review Board 9/1/2019 Illinois Department of Public Health Page A - 1 SECTION A IN-CENTER HEMODIALYSIS Category of Service Inventory of Health Care Facilities and Services and Need Determinations Illinois Health Facilities and Services Review Board 9/1/2019 Illinois Department of Public Health Page A - 2 Planning Process for In-Center Hemodialysis Category of Service For the In-Center Hemodialysis category of service: 1. The planning areas are the designated Health Service Areas 2. The utilization standard is a facility must operate at a minimum of 80 percent utilization rate, assuming three patient shifts per day per renal dialysis station operating six days a week. Inventory of Health Care Facilities and Services and Need Determinations Illinois Health Facilities and Services Review Board 9/1/2019 Illinois Department of Public Health Page A - 3 3. -

Chicago Police Department THIS AGAIN… DEMONSTRATIVE STRUCTURAL CHANGES NEED in POLICING See Page 9

MUSLIMPublished Continuously SinceJOURNAL October 1975! www.MuslimJournal.net Vol. 45, No. 42, July 3, 2020 BRINGING HUMANITY TOGETHER IN MORAL EXCELLENCE WITH TRUTH AND UNDERSTANDING $1.75 - $2.00 outside U.S. INSIDE THIS ISSUE MUSLIM JOURNAL, ONE OF 24 NEWSROOMS TO RECEIVE KNIGHT FOUNDATION GRANT See Page 3 MAY WE NEVER WITNESS Example #1: Chicago Police Department THIS AGAIN… DEMONSTRATIVE STRUCTURAL CHANGES NEED IN POLICING See Page 9 Administration after the mur- der of Laquan McDonald by CPD office Jason Van Dyke. When the Trump admin- istration came to power in 2016, Attorney General Ses- sions scuttled all of the police department investigations, including the one in Chicago. Then State Attorney Gener- CMSEF’S GRADUATES’ al Lisa Madigan filed a law- RECOGNITION & VIRTUAL suit in August 2017 to keep SALUTE the five-year court-ordered See Page 13 consent decree in place. Mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPD Superintendent Brown gave a joint response to this lack of progress, which was to By Bill Chambers ers with Martin Luther King Jr.; 82 percent of which are Black, say the report “illustrates how CHICAGO, Ill. – Chicago is rioting at the Democratic Nation- secretly interrogated at the the level of transformational the only large city in America al Convention in 1968; helping CPD’s Homan Square facility; change and reform that we are with a police force with a “his- murder Fred Hampton Jr. in his Murder and cover-up working towards cannot be tory of racism, surveillance of bed in early morning hours of the of Black men like Laquan achieved overnight.” activists, torture, murder and Black Panther Party; McDonald shot 16 times by Their response reflects a other forms of police violence” The torture of over 200 sus- out of control cop; and most long history of resistance to that have never been reformed. -

Reclaiming a City from Neoliberalism

1 EPICENTER: CHICAGO reclaiming a city from neoliberalism Andrea J. Ritchie in collaboration with Black Lives Matter Chicago INTRODUCTION2 In many ways, all eyes are on Chicago. The city increasingly finds itself at the epicenter of multiple discourses of violence and safety – from hubristic Presidential tweets claiming federal intervention is necessary to address Chicago’s murder rate, to hand-wringing national headlines calling the city the “gang capital” of the United States,1 to threats to send migrants seeking refuge at the border to Sanctuary Cities like Chicago, to everyday corner conversations about the latest shooting, whether by a police officer or community member. Chicago is also a hub of resistance, fighting back against a number of national trends, including racial profiling, police violence, discriminatory “stop and frisk” programs, intensified gang enforcement and surveillance, crimi- nalization of poverty, targeting of migrants, continuing residential segregation, gentrification, attrition of public housing, and privatization of public education and public services. Movements across the country are looking to Chicago’s uniquely intersectional organizing and recent wins on several fronts, including: • securing reparations for survivors of police violence, • re-establishment of a trauma center on the city’s South Side, • Dante Servin's forced resignation two days before a termination hearing. Unfortunately, by allowing Servin to resign the Chicago Police Department preserved his right to receive a full pension. This became -

Money and Punishment, Circa 2020

Money and Punishment, Circa 2020 The Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale Law School Fines & Fees Justice Center Policy Advocacy Clinic at UC Berkeley School of Law Money and Punishment, Circa 2020 Co-Editors Anna VanCleave Director, Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale Law School Brian Highsmith Senior Research Affiliate Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale Law School Judith Resnik Arthur Liman Professor of Law at Yale Law School Jeff Selbin Faculty Director and Clinical Law Professor, Policy Advocacy Clinic at UC Berkeley School of Law Lisa Foster Co-Director, Fines & Fees Justice Center Associate Editors Hannah Duncan, Yale Law School Class of 2021 Stephanie Garlock, Yale Law School Class of 2020 Molly Petchenik, Yale Law School Class of 2021 prepared in conjunction with the 23rd Annual Liman Colloquium Yale Law School, Fall 2020 The Editors appreciate the support of Arnold Ventures, the Vital Projects Fund, and Yale Law School’s Class Action Litigation Fund and its Robert H. Preiskel & Leon Silverman Fund Preface Money has a long history of being used as punishment, and punishment has a long history of being used discriminatorily and violently against communities of color. This volume surveys the many misuses of money as punishment and the range of efforts underway to undo the webs of fines, fees, assessments, charges, and surcharges that undergird so much of state and local funding. Whether in domains that are denominated “civil,” “criminal,” or “administrative,” and whether the needs are about law, health care, employment, housing, education, or safety services, racism intersects with the criminalization of poverty in all of life’s sectors to impose harms felt disproportionately by people of color. -

Envisioning Abolition Democracy

ENVISIONING ABOLITION DEMOCRACY Allegra M. McLeod∗ What is, so to speak, the object of abolition? Not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons, that could have slavery, that could have the wage, and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society. — Fred Moten & Stefano Harney, The University and the Undercommons1 INTRODUCTION For decades, police in Chicago chained people in their custody to the wall in dark, windowless rooms and subjected their captives to beatings, electric shocks, anal rape, and racial abuse.2 In July 2016, members of the #LetUsBreathe Collective, created in the aftermath of numerous police killings in Chicago and elsewhere, occupied vacant lots adjacent to the Chicago Police Department’s Homan Square facility — one of the locations where such abuse occurred.3 The Collective sought justice, not through recourse to the criminal courts or civil litigation, but instead by reconceptualizing justice in connection with efforts to end reliance on ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ∗ Professor, Georgetown University Law Center. I am grateful to Amna Akbar, Geoff Gilbert, Sora Han, Stephen Lee, and Alexandra Natapoff for their careful engagement with this Essay and to workshop participants at the University of California, Irvine School of Law. I owe thanks also to the editors of the Harvard Law Review and to librarians at Georgetown Law for their outstanding work. And I am most grateful to Sherally Munshi for her brilliant ideas and editorial guidance, steadfast support, and inspiration. This Essay is dedicated to our son, Kiran Bayard, with the hope he lives to see a world that comes closer to realizing abolition democracy.