“Memories Seeded in Longings”: an Interview with Bernice Eisenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 New York

CANADA NOW BEST NEW FILMS FROM CANADA 2017 APRIL 6 – 9 AT THE IFC CENTER, NEW YORK From the recent numerous international successes of Canadian directors such as Xavier Dolan (Mommy, It’s Only the End of the World), Denis Villeneuve (Arrival, and the forthcoming Blade Runner sequel), Philippe Falardeau (The Bleeder, The Good Lie) and Jean-Marc Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club, Wild, Demolition), you might be thinking that there must be something special in that clean, cool drinking water north of the 49th parallel. As this year’s selection of impressive new Canadian films reveals, you would not be wrong. With works from new talents as well as from Canada’s accomplished veteran directors, this series will transport you from the Arctic Circle to western Asia, from downtown Montreal to small town Nova Scotia. And yes, there will be hockey. Get ready to travel across the daring and dramatic contemporary Canadian cinematic landscape. Have a look at what’s now and what’s next in those cinematic lights in the northern North American skies. Thursday, April 6, 7:00PM RUMBLE: THE INDIANS WHO ROCKED THE WORLD CANADA 2017 | 97 MINUTES DIRECTOR: CATHERINE BAINBRIDGE, CO-DIRECTOR: ALFONSO MAIORANA Artfully weaving North American musicology and the devastating historical experiences of Native Americans, Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked The World reveals the deep connections between Native American and African American peoples and their musical forms. A Sundance 2017 sensation, Bainbridge’s and co-director Maiorana’s documentary charts the rhythms and notes we now know as rock, blues, and jazz, and unveils their surprising origins in Native American culture. -

DOXA Festival 2004

2 table of contents General Festival Information - Tickets, Venues 3 The Documentary Media Society 5 Acknowledgements 6 Partnership Opportunities 7 Greetings 9 Welcome from DOXA 11 Opening Night - The Take 13 Gals of the Great White North: Movies by Canadian Women 14 Inheritance: A Fisherman’s Story 15 Mumbai, India. January, 2004. The World Social Forum. by Arlene Ami 16 Activist Documentaries 18 Personal Politics by Ann Marie Fleming 19 Sherman’s March 20 NFB Master Class with Alanis Obomsawin 21 Festival Schedule 23 Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel 24 Born Into Brothels 25 The Cucumber Incident 26 No Place Called Home 27 Word Wars 29 Trouble in the Image by Alex MacKenzie 30 The Exhibitionists 31 Haack: The King of Techno + Sid Vision 33 A Night Out with the Guys (Reeking of Humanity) 34 Illustrating the Point: The Use of Animation in Documentary 36 Closing Night - Screaming Men 39 Sources 43 3 4 general festival information Tickets Venues Opening Night Fundraising Gala: The Vogue Theatre (VT) 918 Granville Street $20 regular / $10 low income (plus $1.50 venue fee) Pacific Cinémathèque (PC) 1131 Howe Street low income tickets ONLY available at DOXA office (M-F, 10-5pm) All programs take place at Pacific Cinémathèque except Tuesday May Matinee (before 6 pm) screenings: $7 25 - The Take, which is at the Vogue Theatre. Evening (after 6 pm) screenings: $9 Closing Night: $15 screening & reception The Vogue Theatre and Pacific Cinémathèque are Festival Pass: $69 includes closing gala screening & wheelchair accessible. reception (pass excludes Opening Gala) Master Class: Free admission Festival Information www.doxafestival.ca Festival passes are available at Ticketmaster only (pass 604.646.3200 excludes opening night). -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Published by Strategic Planning and Government Relations P.O. Box 6100, Station Centre-ville Montreal, Quebec H3C 3H5 Internet: onf-nfb.gc.ca/en E-mail: [email protected] Cover page: ANGRY INUK, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril © 2017 National Film Board of Canada ISBN 0-7722-1278-3 2nd Quarter 2017 Printed in Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016–2017 IN NUMBERS MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNMENT FILM COMMISSIONER FOREWORD HIGHLIGHTS 1. THE NFB: A CENTRE FOR CREATIVITY AND EXCELLENCE 2. INCLUSION 3. WORKS THAT REACH EVER LARGER AUDIENCES, RAISE QUESTIONS AND ENGAGE 4. AN ORGANIZATION FOCUSED ON THE FUTURE AWARDS AND HONOURS GOVERNANCE MANAGEMENT SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES IN 2016–2017 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNEX I: THE NFB ACROSS CANADA ANNEX II: PRODUCTIONS ANNEX III: INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS SUPPORTED BY ACIC AND FAP AS THE CROW FLIES Tess Girard August 1, 2017 The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Canadian Heritage Ottawa, Ontario Minister: I have the honour of submitting to you, in accordance with the provisions of section 20(1) of the National Film Act, the Annual Report of the National Film Board of Canada for the period ended March 31, 2017. The report also provides highlights of noteworthy events of this fiscal year. Yours respectfully, Claude Joli-Coeur Government Film Commissioner and Chairperson of the National Film Board of Canada ANTHEM Image from Canada 150 video 6 | 2016-2017 2016–2017 IN NUMBERS 1 VIRTUAL REALITY WORK 2 INSTALLATIONS 2 INTERACTIVE WEBSITES 67 ORIGINAL FILMS AND CO-PRODUCTIONS 74 INDEPENDENT FILM PROJECTS -

Window Horses the Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming Des Mots, Des Couleurs Et Du Son Julie Demers

Document généré le 23 sept. 2021 20:56 Séquences : la revue de cinéma Window Horses The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming Des mots, des couleurs et du son Julie Demers On the beach At night Alone Numéro 308, juin 2017 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/86037ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (imprimé) 1923-5100 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Demers, J. (2017). Compte rendu de [Window Horses : the Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming / Des mots, des couleurs et du son]. Séquences : la revue de cinéma, (308), 35–35. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2017 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ ANN MARIE FLEMING | 35 Window Horses The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming Des mots, des couleurs et du son Le Canada : deux solitudes. Alors que le cinéma québécois est projeté sur écran partout au pays, trop peu de films canadiens traversent les frontières du Québec. Mis à part les Guy Maddin, Atom Egoyan, David Cronenberg et James Cameron, combien de réalisateurs canadiens sont connus et célébrés au Québec ? JULIE DEMERS t pourtant, le cinéma canadien est foisonnant et inventif. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Rocío G

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Rocío G. Davis (December 2013) Degrees: Ph. D. in Literature. University of Navarra, 1991. Received cum laude for Doctoral Dissertation. M.A. in Literature. University of Navarra, 1987. Received cum laude for Master’s Thesis. B.A. in Literature (English). College of Arts and Letters, Ateneo de Manila University, 1985. Academic Appointments (since 2000): March 2010: Acredited as a Catedrático de Universidad in English Philology by the ANECA. March 2010-August 2013: Professor of English, City University of Hong Kong 2000-2001: Visiting Professor of Asian American Literature. University of Illinois, Chicago. 1997 to 2010: Associate Professor of English and American Literature, University of Navarra. June-July 2006: Visiting Scholar at the Centre for the Study of Autobiography, Gender, and Age, University of British Columbia April 2004: Visiting Scholar at the Centre for Research in Women’s Studies and Gender Relations, University of British Columbia Participation in Funded Research Projects: As PI of the Research Group: Title: “’A Noble Duty, Wisely Planned’: An Analysis of Life Writing by the Thomasites, American Teachers Sent to the Philippines in 1901” Funding Organization: College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Grant Dates: March 1, 2011-February 29, 2013 Amount: HK$100,000 (10.000 euros) __________________________________ Title: Autobiografía académica en el siglo xx como historia intelectual y memoria cultural Funding Organization: Gobierno de Navarra Dates: 2008-2010 Amount: 24.000 euros Number of Members: 5 __________________________________ Title: Autobiografía académica en el siglo xx como historia intelectual y memoria cultural Funding Organization: Fundación Universitaria de Navarra Dates: 2007-2008 Amount: 13.500 euros Number of Members: 5 __________________________________________________ 2 Title: Autobiography, History, Literature: Discourse Strategies (La auto/biografía entre la literatura e historia: estrategias del discurso). -

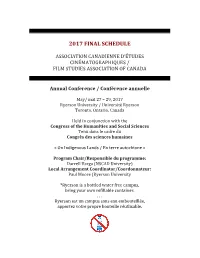

2017 Final Schedule

_________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 FINAL SCHEDULE ASSOCIATION CANADIENNE D’ÉTUDES CINÉMATOGRAPHIQUES / FILM STUDIES ASSOCIATION OF CANADA _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Annual Conference / Conférence annuelle May/ mai 27 – 29, 2017 Ryerson University / Université Ryerson Toronto, Ontario, Canada HeLd in conjunction with the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences Tenu dans Le cadre du Congrès des sciences humaines « On Indigenous Lands / En terre autochtone » Program Chair/Responsible du programme: DarreLL Varga (NSCAD University) Local Arrangement Coordinator/Coordonnateur: Paul Moore (Ryerson University *Ryerson is a bottled water free campus, bring your own refiLLable container. Ryerson est un campus sans eau embouteiLLée, apportez votre propre bouteiLLe réutLisable. ___________________________________________May 26 mai________________________________________ Welcome Gathering / Rassemblement de bienvenue Doors open at 7:00 p.m. Film Screening / Projection CFMDC50: Where Do You Come From? Screening begins at 8pm, running time: 60 mins 2017 marks the Canadian FiLmmakers Distribution Centre’s 50th anniversary, coinciding with Canada’s 150th. Taking a critical pause, Where Do You Come From? considers what this question poses in doing and/or undoing connections to place, Land, home, history, generationaL memory and trauma. The program brings into question CFMDC’s institutional role in the representation -

To Refer to Asian Canadian Film and Video As a Hyphenated Cinema

Being a one-and-a-half-generation Chinese Canadian, you have one foot in and one foot out and no strong sense of belonging. —Julia Kwan It will take a few generations to melt that barrier and, hopefully, that word ‘Asian’ will drop out of the lexicon and we will be identifi ed as Canadians and not as hyphenated ones. —Cheuk Kwan I think a lot about the transitory space that I exist in, the journeyman in me—here, but not here. —Ho Tam NOTES ON HYPHENATION To refer to Asian Canadian fi lm and video as a hyphenated cinema might seem an obvious or unnecessarily controversial move, worrying the exis- tence or non-existence of punctuation marks perhaps a bit like scratching at dissolving stitches aft er they have already been absorbed by the skin. Debates in Asian North American cultural studies over the signifi cance and appropriate use of the hyphen have undoubtedly suff ered from a certain banality—a banality also apparent in the increasingly routine obser- vation that all North Americans are in some sense ‘hyphenated.’ Yet the crux of the discussion has been and remains germane to those situated in, not in and/or between racial and national entities such as ‘Asia’ and ‘Canada’ or ‘Asia’ and ‘America,’ and who continue to seek means to artic- ulate the contradictions and negotiations that bind these categories in their unsett led and mutually unsett ling dynamics. For its multiple charges, and for simply occupying the gaps between identifi ers at once coextensive (or equal), and subordinate and super-ordinate (or unequal), the hyphen still marks a contentious spot on our cultural-political maps; it serves to punctuate an otherwise awkwardly or deceptively empty space.1 Th is mediary space or interval—indeed, in the above quotations from Julia Kwan and Ho Tam, it would seem both a time and a place—has been both easy to overlook and prone to co-optation. -

“Maybe It's Time for a Little History Lesson Here” (P

NOTE: Draft for discussion at HKU Asian American Graphic Narratives Symposium NOT FOR CITATION/CIRCULATION NOTE: Illustrations/photos will be available during the presentation of the paper “Maybe it’s time for a little history lesson here…” Visual Knowledge in The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam Staci Ford (History/American Studies Program, HKU: [email protected]) My paper will be of a slightly different nature than others presented in this symposium as my background is in women’s history/cultural history. Over the past several years I have noticed that my students have come to rely more readily on various graphic narrative‐type representations of history. The “cartoonification” of multiple interpretations of the past has become a way for my students to distill large amounts of information into “chewable bites” as well as to help them remember facts and ideas that they might forget without a visual reminder of meanings. Texts ranging from America: A Cartoon History, and Addicted to War: Why the U.S. Can’t Kick Militarism to Understanding Postfeminism (and in between a host of general histories focusing on various events and time periods) are used not only as shortcuts and time savers, but as ways to cut through what students see as unnecessary jargon, complicated chronological narratives or elaborate historiographical exegesis. As one particularly enthusiastic fan of this genre succinctly put it: “I’d like to have the time to complex‐ify but I have to simplify.” Students also appreciate the ways in which graphic narratives are also often revisionist histories where text and image labor together to make visible that which was previously ignored or marginalized. -

“Memories Seeded in Longings”: an Interview with Bernice Eisenstein Ruth Panofsky

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 04:24 Studies in Canadian Literature Études en littérature canadienne “Memories Seeded in Longings”: An Interview with Bernice Eisenstein Ruth Panofsky Volume 43, numéro 1, 2018 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1058071ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1058071ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) University of New Brunswick, Dept. of English ISSN 0380-6995 (imprimé) 1718-7850 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Panofsky, R. (2018). “Memories Seeded in Longings”: An Interview with Bernice Eisenstein. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, 43(1). https://doi.org/10.7202/1058071ar All Rights Reserved ©, 2019 Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des littérature canadienne services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ “Memories Seeded in Longings”: An Interview with Bernice Eisenstein Ruth Panofsky rtist and writer Bernice Eisenstein (1949- ) was born in Toronto to Polish Holocaust survivors. Her father, Barek (Beryl or Ben) Eisenstein, was from Miechow and her mother, ReginaA Oksenhendler, was from Bedzin; both survived Auschwitz. They immigrated to Canada in 1948 and settled in Toronto’s Kensington Market neighbourhood, where Ben Eisenstein opened a kosher butcher shop. -

News Release for Immediate Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE National Film Board of Canada brings a wealth of BC stories to VIFF 2019 Local perspectives lead the way as nine NFB films and a new augmented reality work debut September 4, 2019 – Vancouver – National Film Board of Canada Powerful stories from across British Columbia and beyond are featured in a selection of 10 new works at the 2019 Vancouver International Film Festival, September 26 to October 11. As a new liquefied natural gas plant in Kitimat promises to bring increasing tanker traffic, VIFF is presenting the North American premiere of Mirjam Leuze’s The Whale and the Raven (Busse & Halberschmidt/Cedar Island Films/NFB/ZDF/ARTE/TOPOS Film/Vizion), illuminating the issues that have drawn whale researchers, the Gitga’at First Nation and the BC government into conflict. Making its Vancouver premiere in VIFF Immersed is East of the Rockies, an augmented reality story from acclaimed Vancouver author Joy Kogawa, produced by Jam3 and the NFB, which follows the experiences of a 17-year-old girl forced to live in BC’s Slocan Japanese internment camp. Three local short works make their BC debuts: Christopher Auchter’s Now Is the Time revisits a day 50 years ago that signalled a cultural rebirth on Haida Gwaii, while Sandra Ignagni’s Highway to Heaven: A Mosaic in One Mile is a poetic look at an utterly unique place of multifaith worship on Richmond’s No. 5 Road. Vancouver director Ann Marie Fleming, whose 2016 Window Horses was named Best BC Film and Canadian Feature at VIFF, is back at the festival with her short Question Period, in which recently settled Syrian refugee women in Vancouver have questions about life in their new home. -

Canada's Top Ten Film Festival

March/ April 2017 special Events Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival Canadian & International Features Toni Erdmann shorts & artist talks Mike Hoolboom & Alex MacKenzie www.winnipegcinematheque.com March 2017 WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 4 5 Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Circus Without Borders / Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Angry Inuk / 7 pm Maliglutit / 7 pm 7 pm & 9 pm Maliglutit / 3 pm & 7 pm Angry Inuk / 3 pm Angry Inuk / 9 pm Angry Inuk / 9:15 pm Maliglutit / 7 pm 8 9 10 11 12 Toni Erdmann / 7 pm Toni Erdmann / 7 pm Architecture+Film: Saturday Morning All-You-Can-Eat Canada’s Top Ten: A Little Chaos / 7 pm Cereal Cartoon Party! / 10 am Hello Destroyer / 3 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Toni Erdmann / 3 pm & 7 pm Toni Erdmann / 7 pm Hello Destroyer / 9 pm 15 16 17 18 19 Toni Erdmann / 7 pm Toni Erdmann / 7 pm Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: canada’s Top Ten: Those Who Make Revolution Halfway, Those Who Make Revolution Halfway, Those Who Make Revolution Halfway, Only Dig Their Own Graves / 7 pm Only Dig Their Own Graves / 3 pm Only Dig Their Own Graves / 3 pm It’s Only the End of the World / 7 pm It’s Only the End of the World / 7 pm Toni Erdmann / 9 pm 22 23 24 25 26 French Film Festival: French Film Festival: French Film Festival: Canada’s Top Ten: Canada’s Top Ten: Daguerreotype / 7 pm Neither Heaven Nor Earth / 7 pm The Wages of Fear / 7 pm Shorts: Part One / 3 pm Shorts: Part Two / 3 pm Oh La La Pauline! / 9 pm Eyes Without a Face / 9:30 pm French Film Festival: Toni Erdmann / 7 pm Diabolique / 7 pm The Stopover -

That's How the Light Gets in As This Long Pandemic

FOLLOW US | SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTER | WWW.CANADANOW.US That’s How The Light Gets In As this long pandemic period is finally starting to lift, we hope you’ll be pleased to know that Canada Now is bringing you a fresh selection of cinematic northern lights to add even more to the gathering brightness. It may not be a perfect solution, but we promise it will help. As our late, great poet Leonard Cohen once wrote, “Forget your perfect offering/There is a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in. And so, let’s let that light in. Sign-up to continue receiving your CANADA NOW newsletter! LONG LIFE, HAPPINESS AND PROSPERITY ► WINDOW HORSES ► THE DEFECTOR ► VENUS ► As part of this annual celebration of the amazing contributions of Asian Canadians to our cultural mosaic, Canada Now is proud to present these impressive films by these filmmakers. Ranging from comedy to drama, animation to documentary, these films reflect experiences and heritages from Central, South, and East Asia through a distinctively Canadian perspective: Sandra Oh stars as a struggling single mother whose daughter decides that Taoist magic will make everything better, in Mina Shum’s LONG LIFE, HAPPINESS AND PROSPERITY; Oh’s voice can also be heard as Rosie, a Chinese Persian Canadian poet invited to a life-altering poetry festival in Iran, in Ann Marie Fleming’s animated marvel, WINDOW HORSES; in Eisha Marjara’s witty comic drama of identity, VENUS, transitioning woman Sid is surprised to learn that 14 years ago she became a father and now her son wants to get to know his lost parent; Ann Shin’s intense documentary, THE DEFECTOR: ESCAPE FROM NORTH KOREA, moves us through the shadowy worlds of human smuggling along the dangerous Chinese-North Korean border.