Port and Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Campaigners of Lndian National Congress for West Benqal

, ph .230184s2 $ t./r. --g-tv ' "''23019080 INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 24, AKBAR ROAD, NEW DELHI'110011 K.C VENUGOPAL, MP General Secretary PG-gC/ }:B U 12th March,2021 The Secretary Election Commission of lndia Nirvachan Sadan New Delhi *e Sub: Star Campaigners of lndian National Congress for West Benqal. 2 Sir, The following leaders of lndian National Congress, who would be campaigning as per Section 77(1) of Representation of People Act 1951, for the ensuing First Phase '7* of elections to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengat to be held on 2ffif M-arch br,*r% 2021. \,/ Sl.No. Campaiqners Sl.No. Campaiqners \ 1 Smt. Sonia Gandhi 16 Shri R"P.N. Sinqh 2 Dr. Manmohan Sinqh 17 Shri Naviot Sinqh Sidhu 3 Shri Rahul Gandhi 18 ShriAbdul Mannan 4 Smt. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra 19 Shri Pradip Bhattacharva w 5 Shri Mallikarjun Kharqe 20 Smt. Deepa Dasmunsi 6 ShriAshok Gehlot 21 Shri A.H. Khan Choudhary ,n.T 7 Capt. Amarinder Sinqh 22 ShriAbhiiit Mukheriee 8 Shri Bhupesh Bhaohel 23 Shri Deependra Hooda * I Shri Kamal Nath 24 Shri Akhilesh Prasad Sinqh 10 Shri Adhir Ranian Chowdhury 25 Shri Rameshwar Oraon 11 Shri B.K. Hari Prasad 26 Shri Alamqir Alam 12 Shri Salman Khurshid 27 Mohd Azharuddin '13 Shri Sachin Pilot 28 Shri Jaiveer Sherqill 14 Shri Randeep Singh Suriewala 29 Shri Pawan Khera 15 Shri Jitin Prasada 30 Shri B.P. Sinqh This is for your kind perusal and necessary action. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, IIt' I \..- l- ;i.( ..-1 )7 ,. " : si fqdq I-,. elS€ (K.C4fENUGOPAL) I t", j =\ - ,i 3o Os 'Ji:.:l{i:,iii-iliii..d'a !:.i1.ii'ji':,1 s}T ji}'iE;i:"]" tiiaA;i:i:ii-q;T') ilem€s"m} il*Eaacr:lltt,*e Ge rt r; l-;a. -

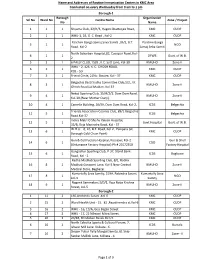

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

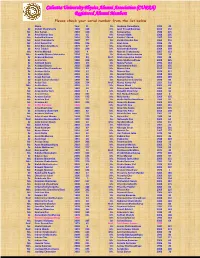

Calcutta University Physics Alumni Association (CUPAA) Registered Alumni Members Please Check Your Serial Number from the List Below Name Year Sl

Calcutta University Physics Alumni Association (CUPAA) Registered Alumni Members Please check your serial number from the list below Name Year Sl. Dr. Joydeep Chowdhury 1993 45 Dr. Abhijit Chakraborty 1990 128 Mr. Jyoti Prasad Banerjee 2010 152 Mr. Abir Sarkar 2010 150 Dr. Kalpana Das 1988 215 Dr. Amal Kumar Das 1991 15 Mr. Kartick Malik 2008 205 Ms. Ambalika Biswas 2010 176 Prof. Kartik C Ghosh 1987 109 Mr. Amit Chakraborty 2007 77 Dr. Kartik Chandra Das 1960 210 Mr. Amit Kumar Pal 2006 136 Dr. Keya Bose 1986 25 Mr. Amit Roy Chowdhury 1979 47 Ms. Keya Chanda 2006 148 Dr. Amit Tribedi 2002 228 Mr. Krishnendu Nandy 2009 209 Ms. Amrita Mandal 2005 4 Mr. Mainak Chakraborty 2007 153 Mrs. Anamika Manna Majumder 2004 95 Dr. Maitree Bhattacharyya 1983 16 Dr. Anasuya Barman 2000 84 Prof. Maitreyee Saha Sarkar 1982 48 Dr. Anima Sen 1968 212 Ms. Mala Mukhopadhyay 2008 225 Dr. Animesh Kuley 2003 29 Dr. Malay Purkait 1992 144 Dr. Anindya Biswas 2002 188 Mr. Manabendra Kuiri 2010 155 Ms. Anindya Roy Chowdhury 2003 63 Mr. Manas Saha 2010 160 Dr. Anirban Guha 2000 57 Dr. Manasi Das 1974 117 Dr. Anirban Saha 2003 51 Dr. Manik Pradhan 1998 129 Dr. Anjan Barman 1990 66 Ms. Manjari Gupta 2006 189 Dr. Anjan Kumar Chandra 1999 98 Dr. Manjusha Sinha (Bera) 1970 89 Dr. Ankan Das 2000 224 Prof. Manoj Kumar Pal 1951 218 Mrs. Ankita Bose 2003 52 Mr. Manoj Marik 2005 81 Dr. Ansuman Lahiri 1982 39 Dr. Manorama Chatterjee 1982 44 Mr. Anup Kumar Bera 2004 3 Mr. -

West Bengal Towards Change

West Bengal Towards Change Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Research Foundation Published By Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 Web :- www.spmrf.org, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone:011-23005850 Index 1. West Bengal: Towards Change 5 2. Implications of change in West Bengal 10 politics 3. BJP’s Strategy 12 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 14 Statements on West Bengal – excerpts 5. Statements of BJP National President 15 Amit Shah on West Bengal - excerpts 6. Corrupt Mamata Government 17 7. Anti-people Mamata government 28 8. Dictatorship of the Trinamool Congress 36 & Muzzling Dissent 9. Political Violence and Murder in West 40 Bengal 10. Trinamool Congress’s Undignified 49 Politics 11. Politics of Appeasement 52 12. Mamata Banerjee’s attack on India’s 59 federal structure 13. Benefits to West Bengal from Central 63 Government Schemes 14. West Bengal on the path of change 67 15. Select References 70 West Bengal: Towards Change West Bengal: Towards Change t is ironic that Bengal which was once one of the leading provinces of the country, radiating energy through its spiritual and cultural consciousness across India, is suffering today, caught in the grip Iof a vicious cycle of the politics of violence, appeasement and bad governance. Under Mamata Banerjee’s regime, unrest and distrust defines and dominates the atmosphere in the state. There is a no sphere, be it political, social or religious which is today free from violence and instability. It is well known that from this very land of Bengal, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore had given the message of peace and unity to the whole world by establishing Visva Bharati at Santiniketan. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

Alcove Flora Fountain

https://www.propertywala.com/alcove-flora-fountain-kolkata Alcove Flora Fountain - Topsia, Kolkata An embodiment of refreshing water bodies and sprawling landscaped greens Alcove Flora Fountain is presented by Alcove Realty at Tangra, Topsia, Kolkata offers residential project that hosts 2, 3 and 4 BHK apartment with good features Project ID: J289645611 Builder: Alcove Realty Location: Flora Fountain, Tangra, Topsia, Kolkata - 700046 (West Bengal) Completion Date: Dec, 2021 Status: Started Description Alcove Flora Fountain by Alcove Realty located at Tangra, Topsia, Kolkata redefines the standard of living with architectural excellence. Project spread over 899 sq. ft.-1882 sq. ft. comprising of 2,3 and 4 bhk apartments. The project is equipped with key amenities including fire safety systems, swimming pool, kids pool etc. & well connected with other parts of city and has all the basic utilities. RERA ID : HIRA/P/KOL/2018/000050 Amenities: swimming pool kids pool locker facilities an AC lounge outdoor yoga deck Alcove Reaqlty, One of the most renowned, trusted and exemplary name in the sphere of real estate - Alcove Realty, spearheaded by the legendary Mr. Amar Nath Shroff, came into existence to set an indelible benchmark with its landmark projects. With forty glorious years of experience, this ‘3 Generation’ company is beheld with distinction and respect among all the renowned builders in Kolkata, at the helm of the industry. Features Security Features Exterior Features Fire Alarm Reserved Parking Recreation Land Features Swimming Pool -

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 21.07.2021 Father/ District/PC Name PS of District/PC of Case/ GDE SL

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 21.07.2021 Father/ District/PC Name PS of District/PC of Case/ GDE SL. No Alias Sex Age Spouse Address Ps Name Name of Accused residence residence Ref. Name Accused of Purba Salbari, P.O.-Purba Kumargram Salbari, PS- PS Case No : Thagendra Ganeshrav 1 M 36 Kumargram Dist- Kumargram Alipurduar Kumargram Alipurduar 142/21 US- Rava a Alipurduar PS: 498A/304B/3 Kumargram 4 IPC Dist.: Alipurduar Alipurduar PS Ram Case No : 2 Kholaban M Not Alipurduar Alipurduar 229/21 US- Sha 448/323/379/ 506/34 IPC Alipurduar PS Case No : Bimal 3 Not Alipurduar Alipurduar 230/21 US- Singh 448/323/354/ 506/34 IPC Alipurduar PS SUBARNA PUR Case No : Rukil Lt.upen COLONY PS: 225/21 US- 4 M 59 Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Barman Barman Alipurduar Dist.: 448/323/325/ Alipurduar 307/506/34 IPC Malangi TG, Shyam Bandhana Hasimara PS: Jaigaon PS 5 M 25 Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar Lohar Lohar Jaigaon Dist.: GDE No. 569 Alipurduar Jhupripatty, Md. Sahajuddi New Hasimara Jaigaon PS 6 Sahidul M 24 Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar n Sekh PS: Jaigaon Dist.: GDE No. 569 Islam Alipurduar Beech TG, Sudhir Mangra Hasimara PS: Jaigaon PS 7 M 26 Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar Kujur Kujur Jaigaon Dist.: GDE No. 569 Alipurduar Dalsingpara, Sagar Adiman busty PS: Jaigaon PS 8 M 27 Jaigaon Alipurduar Jaigaon Alipurduar Lama Lama Jaigaon Dist.: GDE No. 569 Alipurduar PUTIMARI PS: Bisadu Lt Purbil Samuktala PS 9 M 35 Samuktala Dist.: Samuktala Alipurduar Samuktala Alipurduar Barman Barman GDE No. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 14

A Professional Journal of National Defence College Volume 14 Number 2 December 2015 National Defence College Bangladesh EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Patron Lieutenant General Chowdhury Hasan Sarwardy, BB, SBP, ndc, psc Editor-in-Chief Air Vice Marshal Mahmud Hussain, OSP, ndc, psc, GD(P) Editor Colonel Md Mahbub-ul Alam, afwc, psc Associate Editors Colonel Muhammad Wasim-ul Haq, afwc, psc Lieutenant Colonel A N M Foyezur Rahman, psc, Engrs Assistant Editors Lecturer Khadijatul Kobra Civilian Staff Officer Md Nazrul Islam DISCLAIMER The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NDC, Bangladesh Armed Forces or any other agencies of Bangladesh Government. Statement, fact or opinion appearing in NDC Journal are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the editors or publisher. INITIAL SUBMISSION Initial Submission of manuscripts and editorial correspondence should be sent to the National Defence College, Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216, Bangladesh. Tel: 88 02 9003087, Fax: 88 02 8034715, E mail : [email protected]. Authors should consult the Notes for Contributions at the back of the Journal before submitting their final draft. The editors cannot accept responsibility for any damage to or loss of manuscripts. ISSN: 1683-8475 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electrical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without -

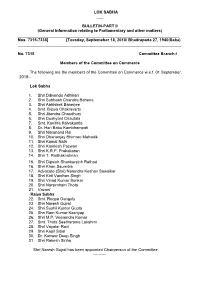

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating To

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ________________________________________________________________________ Nos. 7315-7338] [Tuesday, Septemeber 18, 2018/ Bhadrapada 27, 1940(Saka) _________________________________________________________________________ No. 7315 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Commerce The following are the members of the Committee on Commerce w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Shri Dibyendu Adhikari 2. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 3. Shri Abhishek Banerjee 4. Smt. Bijoya Chakravarty 5. Shri Jitendra Chaudhury 6. Shri Dushyant Chautala 7. Smt. Kavitha Kalvakuntla 8. Dr. Hari Babu Kambhampati 9. Shri Nityanand Rai 10. Shri Dhananjay Bhimrao Mahadik 11. Shri Kamal Nath 12. Shri Kamlesh Paswan 13. Shri K.R.P. Prabakaran 14. Shri T. Radhakrishnan 15. Shri Dipsinh Shankarsinh Rathod 16. Shri Khan Saumitra 17. Advocate (Shri) Narendra Keshav Sawaikar 18. Shri Kirti Vardhan Singh 19. Shri Vinod Kumar Sonkar 20. Shri Narsimham Thota 21. Vacant Rajya Sabha 22. Smt. Roopa Ganguly 23. Shri Naresh Gujral 24. Shri Sushil Kumar Gupta 25. Shri Ram Kumar Kashyap 26. Shri M.P. Veerendra Kumar 27. Smt. Thota Seetharama Lakshmi 28. Shri Vayalar Ravi 29. Shri Kapil Sibal 30. Dr. Kanwar Deep Singh 31. Shri Rakesh Sinha Shri Naresh Gujral has been appointed Chairperson of the Committee. ---------- No.7316 Committee Branch-I Members of the Committee on Home Affairs The following are the members of the Committee on Home Affairs w.e.f. 01 September, 2018:- Lok Sabha 1. Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Balyan 2. Shri Prem Singh Chandumajra 3. Shri Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury 4. Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar 5. Shri Ramen Deka 6. -

Consolidated Daily Arrest Report Dated 30.05.2021 Sl

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 30.05.2021 SL. No Name Alias Sex Age Father/ Address PS of residence District/PC of Ps Name District/PC Name of Case/ GDE Ref. Accused Spouse residence Accused Name 1 Babu Madan M Narayan Joluka, P.O. Kalchini Alipurduar Kalchini PS Case No : Sharma Sharma Tungidighi 06/21 US-302 IPC 2 Rabi Barman M 58 Lt DANGI COLONY PS: Samuktala Alipurduar Samuktala Alipurduar Samuktala PS Case No : Mahendra Samuktala Dist.: 52/21 US-498A/326 IPC Barman Alipurduar 3 Rabindra M 23 Samir Kanthalbari PS: Falakata Alipurduar Falakata Alipurduar Falakata PS Case No : Barman Barman Falakata Dist.: 243/21 US-498(A)/304(B) Alipurduar IPC 4 Abdul Majid M 41 Lt Abbas Chengmaritari PS: Falakata Alipurduar Falakata Alipurduar Falakata PS Case No : Ali Falakata Dist.: 242/21 US-498(A)/306 Alipurduar IPC 5 Kartick Das M 38 Lt- GHATPAR PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Sudharsha Alipurduar Dist.: 1231 n Das Alipurduar 6 Ranjan Das M 39 Lt- Upen SHILBARIHAT PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Das Alipurduar Dist.: 1231 Alipurduar 7 Biswajit Roy M 27 Haridas UTTAR SONAPUR PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Roy Alipurduar Dist.: 1231 Alipurduar 8 Parimal Roy M 37 Dwijendra UTTAR SONA[PUR Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Roy PS: Alipurduar Dist.: 1231 Alipurduar 9 Joydeb M 38 Jiban PALASHBARI PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No. Mandal Mandal Alipurduar Dist.: 1231 Alipurduar 10 Sudeb M 26 Jiban PALASHBARI PS: Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar Alipurduar PS GDE No.