Commuting in London and the South East – Some Background Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in Stroke Mortality in Greater London and South East England

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1997;51:121-126 121 Trends in stroke mortality in Greater London J Epidemiol Community Health: first published as 10.1136/jech.51.2.121 on 1 April 1997. Downloaded from and south east England-evidence for a cohort effect? Ravi Maheswaran, David P Strachan, Paul Elliott, Martin J Shipley Abstract to London to work in the domestic services Objective and setting - To examine time where they generally had a nutritious diet. A trends in stroke mortality in Greater Lon- study of proportional mortality from stroke don compared with the surrounding South suggested that persons born in London retained East Region of England. their lower risk of stroke when they moved Design - Age-cohort analysis based on elsewhere,3 but another study which used routine mortality data. standardised mortality ratios suggested the op- Subjects - Resident population aged 45 posite - people who moved to London acquired years or more. a lower risk of fatal stroke.4 Main outcome measure - Age specific While standardised mortality ratios for stroke stroke mortality rates, 1951-92. for all ages in Greater London are low, Health Main results - In 1951, stroke mortality of the Nation indicators for district health au- was lower in Greater London than the sur- thorities suggest that stroke mortality for rounding South East Region in all age Greater London relative to other areas may bands over 45. It has been declining in vary with age.5 both areas but the rate ofdecline has been The aim of this study was to examine time significantly slower in Greater London trends for stroke mortality in Greater London (p<0.0001). -

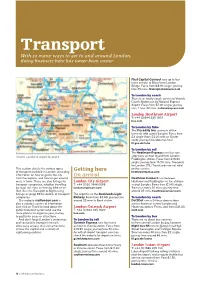

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

South East Greater London Wales East of England West

2021 REVALUATION: REGIONAL WINNERS & LOSERS Roll over the region titles below to find out These figures have been extracted from CoStar and are based on the anticipated changes in rateable values within each individual Administrative area across England and Wales. The extent of your change in rateable value will depend on the exact location of your property. Even if you are in an area where rateable values are predicted to fall, it is important to have your assessment verified, as there may still be opportunities to secure further reductions. For a detailed analysis of the likely impact of the 2021 revaluation and advice on what to do next, please contact a member of our Business Rates team. Email us at [email protected] or visit us at lsh.co.uk INDUSTRIAL REGION AVERAGE GROWTH MIN GROWTH MIN LOCATION MAX GROWTH MAX LOCATION WALES 27% 17% Blaenau Gwent 50% Neath Port Talbot GREATER LONDON 38% 34% Hackney 44% Harrow SOUTH EAST 27% 14% Dover 44% Milton Keynes EAST OF ENGLAND 31% 18% South Norfolk 44% Brentwood EAST MIDLANDS 27% 16% Derby 36% Hinckley NORTH WEST 25% 15% Barrow-In-Furness 35% Liverpool SOUTH WEST 19% 14% West Devon 27% Swindon WEST MIDLANDS 19% 14% Tamworth 26% Solihull NORTH EAST 18% 14% South Tyneside 26% Darlington YORKSHIRE 16% 11% Doncaster 21% Hull & THE HUMBER ALL UK AVG 25% OFFICE REGION AVERAGE GROWTH MIN GROWTH MIN LOCATION MAX GROWTH MAX LOCATION EAST OF ENGLAND 23% 9% Norwich 44% Watford SOUTH WEST 18% 7% Devon 41% Bristol Core GREATER LONDON 20% 5% Covent Garden 37% Sutton SOUTH EAST 25% 17% Reading Central 33% -

Airport Surface Access Strategy 2012-2017

Airport Surface Access Strategy 2012-2017 Contents 1 Introduction 4 APPENDIX A – LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT SERVICES 36 2 Vision 6 APPENDIX B – TRAFFIC FLOWS 40 3 Policy Context 8 APPENDIX C – PASSENGER SURFACE ACCESS 41 3.2 National 8 C.1 Passenger Numbers 41 3.3 Local 8 C.2 Passenger Journeys by time of day 41 C.3 CAA Passenger Survey 43 4 London Luton Airport Today 10 C.4 Passenger Mode Shares 44 4.2 Bus and Coach 10 C.5 Passenger Mode Shares – by journey purpose and UK/non-UK origin 44 4.3 Rail 12 C.6 Passenger Catchment 46 4.4 On-site Bus Services 14 C.7 Passenger Mode Shares – by catchment 48 4.5 Road Access 14 C.8 Car and Taxi Use – by catchment 52 4.6 Car Parking 17 4.7 Taxis 18 APPENDIX D – STAFF SURFACE ACCESS 54 4.8 Walking and Cycling 18 D.1 Introduction 54 4.9 Accessibility 18 D.2 Staff Journeys – by time of day 54 4.10 Central Terminal Area 18 D.3 Staff Mode Shares 55 4.11 Onward Travel Centre 18 D.4 Staff Catchment 57 4.12 Staff Travelcard Scheme 19 D.5 Staff Mode Shares – by catchment 58 4.13 Employee Car Share Scheme 19 APPENDIX E – DfT ASAS GUIDANCE (1999) 59 5 Travel Patterns Today 20 5.1 Passenger Numbers 20 5.2 Passenger Mode Shares 20 5.3 Comparative Performance 22 5.4 Passenger Catchment 23 5.5 Achieving Mode Shift 24 5.6 Staff Travel 24 6 Objectives and Action Plans 26 6.2 Passengers 26 6.3 Staff 30 7 Stakeholder Engagement, Consultation and Monitoring 32 7.1 Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation 32 7.2 Airport Transport Forum 32 7.3 Monitoring 32 7.4 Reporting on Progress 34 2 Airport Surface Access Strategy 2012-2017 Contents 3 London Luton Airport is the fi fth busiest “passenger airport in the UK, with excellent transport links connecting it to London, the South East, the East of“ England Introduction and the South Midlands 11.1.1 London Luton Airport is the fi fth 1.1.3 This ASAS sets out challenging 1.1.5 The Strategy is divided into the busiest passenger airport in the new targets, with a view to building on following sections: UK, with excellent transport links this success. -

Land Use United Kingdom

The Governance of Land Use United Kingdom The planning system Levels of government and their responsibilities The United Kingdom is a unitary state with three devolved governments in Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland, respectively. At the local level, 389 local authorities with varying status and powers exist. Among them are 27 county councils, which exist in parts of England and are strictly speaking an intermediate level of government because they operate above other local authorities, except where they are unitary authorities. The UK government is responsible for allocating funds to local authorities and for preparing the National Planning Policy Framework in England. It can also facilitate important infrastructure projects through specific legislation or by placing them under direct ministerial control. The Welsh and Scottish governments have been granted far reaching powers regarding land-use policies. They enact national spatial planning frameworks that structure the planning system in their territories. The Scottish government also prepares a Scottish Land Use Strategy, the only such document in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, both governments decide about appeals against local planning decisions and have the power to fast track infrastructure project in their territories. Local authorities are responsible for local land-use planning and public housing. They also decide on planning applications. Some local authorities have contracted land-use planning out to the private sector. County councils as an intermediate level of government are – where they exist – responsible for strategic planning and for planning applications related to waste disposal sites, mineral extraction and county owned land. In London, the Greater London Authority has a distinct legal status as a metropolitan authority and is among other issues responsible for transport and for the preparation of the London Plan, a strategic plan that provides binding guidelines to local authorities in the greater London area. -

Greater London Authority

GREATER LONDON AUTHORITY NOTICE OF ELECTION ELECTION OF MAYOR OF LONDON AND LONDON-WIDE MEMBERS OF THE LONDON ASSEMBLY DATE OF THE POLL 1. In the event of a contest, the date of the poll will be Thursday, 6 May 2021. NOMINATION PAPERS 2. Nomination papers to stand in the elections for the Mayor of London and the 11 London-wide Members (party list and individual) of the London Assembly may be obtained from the office of the Greater London Returning Officer, City Hall, The Queen’s Walk, More London, London SE1 2AA on working days between 9am and 4.30pm. Nomination packs can be downloaded at: https://www.londonelects.org.uk/im-candidate/nominations DELIVERY OF NOMINATION PAPERS 3. Completed nomination papers must be delivered in person and hardcopy (not by email) to the Greater London Returning Officer, Committee Room 1, Lower Ground Floor, City Hall, The Queen’s Walk, More London, London SE1 2AA, on any weekday from the date of this notice between 9am and 4.30pm, but by no later than 4pm on Tuesday 30 March 2021. PAYMENT OF DEPOSITS 4. The deposit for each Mayoral candidate is £10,000. The deposit for each party list or individual candidate in the election of London-wide Members is £5,000. Payment should be made by electronic transfer into the GLA Income Account (Royal Bank of Scotland; sort code 16-00-38; account number 00780445). Payment can also be made by cash or bankers draft (banks operating in the UK only). Cleared funds must be received by 4pm on Tuesday 30 March 2021. -

A Mayor and Assembly for London: 10 Years On

2 July 2010 A Mayor and Assembly for London: 10 years on Tony Travers and Christine Whitehead A brief history… It is 10 years since the Greater London Authority was created as a metropolitan or regional tier of government for London. There have been five different arrangements of ‘upper tier’ government in the capital since the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was created in 1855 to build infrastructure. The MBW was succeeded by the London County Council (LCC), a powerful authority for the inner part of the contemporary city. Within this area 28 metropolitan boroughs and the City of London delivered ‘local’ services. Two factors were particularly important in influencing the progress of London’s government. First, the physical expansion of the city created demands for provision across a wider area than the City of London’s original and long-evolved ‘square mile’. The Metropolitan Police Service was created by the government in 1829 to meet the law and order requirements of a fast-growing city. The squalor and chaos of the London of the 1850s prompted Parliament to legislate for London’s first-ever metropolitan government, an indirectly-elected entity. Further physical expansion between the end of the 19 th century and 1939 generated a debate about the need for a ‘Greater London’ government 1. The second important factor in determining the kinds of institutions that emerged was the local power and parochialism of both the City of London and the parish-based or ad hoc bodies that developed to deliver services in the absence of a city-wide government. -

The Planning Game—English Style Or the Greater London Development Plan, 7 Urb

Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law Volume 7 January 1974 The lP anning game—English Style or the Greater London Development Plan Victor Moore Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Victor Moore, The Planning game—English Style or the Greater London Development Plan, 7 Urb. L. Ann. 57 (1974) Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLANNING GAME-ENGLISH STYLE OR THE GREATER LONDON DEVELOPMENT PLAN VICTOR MOORE* Anglophiles will be aware that since the statute Quia Emptores in the year 1290, no single piece of legislation has made as great an im- pact on English land law as that brought about by the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947.1 The lynchpin of that legislation, which gave to England its first comprehensive statutory machinery for controlling land use, was that no landowner could develop his land without first obtaining permission from the local planning authority.2 The content of the development plan which local plan- ning authorities were required to prepare for their areas determined whether permission would be granted, or granted subject to condi- tions, or whether the planning authority would begin cease and desist proceedings if development commenced without permission.' The history of these development plans is well known. -

The Greater London (Restriction of Goods Vehicles) Traffic Order 1985

GREATER LONDON COUNCIL TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT ORDER 1985 No. 343 The Greater London (Restriction of Goods Vehicles) Traffic Order 1985 Made 15 July 1985 Coming into operation 16 December 1985 As amended to January 2010 by 9 Amendment Orders The Greater London Council (hereinafter called ‘the Council’), after consulting the Commissioner of City of London Police, the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, the Common Council of the City of London, and the Councils of all the London Boroughs, in exercise of the powers conferred by section 6 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, and of all other powers thereunto enabling hereby make the following Order:- 1. This Order shall come into operation on 16 December 1985 and may be cited as the Greater London (Restriction of Goods Vehicles) Traffic Order 1985. 2.– (1) In this Order:– “Blackwall Tunnel Northern Approach” has the same meaning as in the Tower Hamlets (Prescribed Routes) (No. 5) Traffic Order 1979; “East Cross Route” has the same meaning as in the Hackney and Tower Hamlets (Various Prohibitions and Restrictions) (No. 1) Traffic Order 1979; “Enactment” means any enactment, whether public, general or local, and includes any order, byelaw, rule, regulation, scheme or other instrument having effect by virtue of an enactment and any reference in this Order to any enactment shall be construed as a reference to that enactment as amended, applied, consolidated, re-enacted by or as having effect by virtue of any subsequent enactment; “Highway Maintainable at the Public Expense” has the same -

UNITED KINGDOM Europe UNITARY COUNTRY

UNITED KINGDOM EUROPe UNITARY COUNTRY Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - HIGH INCOME: OECD Local currency - Pound Sterling (GBP) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 242 509 km2 GDP: 2 597.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 40 210 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), 64.597 REAL GDP GROWTH: 2.9% (2014 vs 2013) an increase of 0.7% per year (2010-14) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 6.1% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 266 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 45 457 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 82.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 17% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: London (16% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.907 (very high), rank 14 Sources: OECD, Eurostat, World Bank, UNDP, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSABILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 389 27 3 419 local authorities County councils and Greater Devolved nations Average municipal size: London Authority 166 060 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The United Kingdom is a unitary state composed of four constituent countries (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales) and three devolved administrations (Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales), having their own elected assembly and government since the devolution process in 1998. The project of devolution of limited political powers to elected regional assemblies in England has been suspended indefinitely following the rejection of the first referendum held in the North-East of England in 2004. The territorial organisation is highly complex and differs greatly between the different countries. -

RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN a Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran

A PORTRAIT OF MODERN BRITAIN RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN A Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), Richard Ehrman (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Virginia Fraser, David Frum, Edward Heathcoat Amory, David Meller, Krishna Rao, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Charles Stewart-Smith and Simon Wolfson About the Authors Rishi Sunak is Head of Policy Exchange’s new Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Research Unit. Prior to joining Policy Exchange, Rishi worked for over a decade in business, co-founding a firm that invests in the UK and abroad. He is currently a director of Catamaran Ventures, a family-run firm, backing and serving on the boards of various British SMEs. He worked with the Los Angeles Fund for Public Education to use new technology to raise standards in schools. He is a Board Member of the Boys and Girls Club in Santa Monica, California and a Governor of the East London Science School, a new free school based in Newham. -

United Kingdom

Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020 provides a comprehensive assessment of how regions and cities across the OECD are progressing in a number of aspects connected to economic development, health, well-being and net zero-carbon transition. In the light of the health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the report analyses outcomes and drivers of social, economic and environmental resilience. Consult the full publication here. OECD REGIONS AND CITIES AT A GLANCE - COUNTRY NOTE UNITED KINGDOM A. Resilient regional societies B. Regional economic disparities and trends in productivity C. Well-being in regions D. Industrial transition in regions E. Transitioning to clean energy in regions F. Metropolitan trends in growth and sustainability The data in this note reflect different subnational geographic levels in OECD countries: • Regions are classified on two territorial levels reflecting the administrative organisation of countries: large regions (TL2) and small regions (TL3). Small regions are classified according to their access to metropolitan areas (see https://doi.org/10.1787/b902cc00-en). • Functional urban areas consists of cities – defined as densely populated local units with at least 50 000 inhabitants – and adjacent local units connected to the city (commuting zones) in terms of commuting flows (see https://doi.org/10.1787/d58cb34d-en). Metropolitan areas refer to functional urban areas above 250 000 inhabitants. Disclaimer: https://oecdcode.org/disclaimers/territories.html Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020 Austria country note 2 A. Resilient regional societies Greater London and South East England have the highest potential for remote working A1. Share of jobs amenable to remote working, 2018 Large regions (TL2, map) LUX GBR AUS SWE CHE NLD ISL DNK FRA FIN NOR BEL LTU EST IRL GRC DEU AUT LVA SVN OECD30 PRT HRV POL ITA USA CZE HUN CAN ESP ROU SVK BGR TUR COL 0 10 20 30 40 50 % The share of jobs amenable to remote working ranges from close to 54% in Greater London to less than 36% in North-East England (Figure A1).