Full Page Photo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society

Volume 28: Number 1 > Winter/Spring 2011 PalmettoThe Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society Protecting Endangered Plants in Panhandle Parks ● Native or Not? Carica papaya ● Water Science & Plants Protecting Endangered Plant Species Sweetwater slope: Bill and Pam Anderson To date, a total of 117 listed taxa have been recorded in 26 panhandle parks, making these parks a key resource for the protection of endangered plant species. 4 ● The Palmetto Volume 28:1 ● Winter/Spring 2011 in Panhandle State Parks by Gil Nelson and Tova Spector The Florida Panhandle is well known for its natural endowments, chief among which are its botanical and ecological diversity. Approximately 242 sensitive plant taxa occur in the 21 counties west of the Suwannee River. These include 15 taxa listed as endangered or threatened by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), 212 listed as endangered or threatened by the State of Florida, 191 tracked by the Florida Natural Areas Inventory, 52 candidates for federal listing, and 7 categorized by the state as commercially exploited. Since the conservation of threatened and endangered plant species depends largely on effective management of protected populations, the occurrence of such plants on publicly or privately owned conservation lands, coupled with institutional knowledge of their location and extent is essential. District 1 of the Florida Sarracenia rosea (purple pitcherplant) at Ponce de Leon Springs State Park: Park Service manages 33 state parks encompassing approximately Tova Spector, Florida Department of Environmental Protection 53,877 acres in the 18 counties from Jefferson County and the southwestern portion of Taylor County westward. -

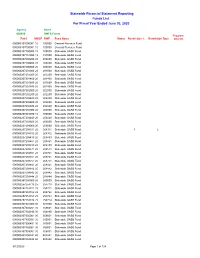

Funds List for Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020

Statewide Financial Statement Reporting Funds List For Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 Agency Name 000000 SWFS Funds Program Fund SWGF SWF Fund Name Status Restriction % Restriction Type Interest 000000101000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107000001 10 100000 General Revenue Fund 000000107100000 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000157151000 15 151000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200200 20 200200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200400 20 200400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207200800 20 200800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201000 20 201000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201200 20 201200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201400 20 201400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201600 20 201600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207201800 20 201800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202000 20 202000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202200 20 202200 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202400 20 202400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202600 20 202600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207202800 20 202800 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203000 20 203000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203200 10 100000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203400 20 203400 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207203600 20 203600 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208000 20 208000 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208311 20 208311 Statewide GASB Fund 1 L 000000207208312 20 208312 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208439 20 208439 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208461 20 208461 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208489 20 208489 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208571 20 208571 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208701 20 208701 Statewide GASB Fund 000000207208721 20 208721 -

Description of the Proposed Action

United States Department of the Interior FIS H AND WILDLIFE SERVICE South Florida Ecological Services Office 1339 20 111 Street Vero Beach. Florida 32960 Service Log Number: 41910-2011-F-0170 March 13, 2015 Alan M. Dodd, Colonel District Commander U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 701 San Marco Boulevard, Room 3 72 Jacksonville, Florida 32207-8175 Dear Colonel Dodd: This letter transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's revised Statewide Programmatic Biological Opinion (SPBO) for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) Civil Works and Regulatory sand placement activities in Florida and their effects on the following sea turtles: Northwest Atlantic Ocean distinct population segment (NW AO DPS) of loggerhead (Carella caretta) and its designated terrestrial critical habitat; green (Chelonia mydas); leatherback (Dermoche!ys coriacea); hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata); and Kemp's ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) ; and the following beach mice: southeastern (Peromyscus polionotus niveiventris); Anastasia Island (Peromyscus polionolus phasma); Choctawhatchee (Peromyscus polionotus a!lophrys); St. Andrews (Peromyscus polionotus peninsularis) ; and Perdido Key (Peromyscus polionotus trissyllepsis) and their designated critical habitat. It does not address effects of these activities on the non-breeding piping plover (Charadrius melodus) and its designated critical habitat or for the red knot (Calidris canutus rufa), a species currently proposed for listing. Effects of Corps planning and regulatory shore protection activities on the non-breeding piping plover and its designated critical habitat within the North Florida Ecological Services office area of responsibility and the South Florida Ecological Services office area of responsibility are addressed in the Service's May 22, 2013, Programmatic Piping Plover Biological Opinion. -

FLORIDA STATE PARKS FEE SCHEDULE (Fees Are Per Day Unless Otherwise Noted) 1. Statewide Fees Admission Range $1.00**

FLORIDA STATE PARKS FEE SCHEDULE (Fees are per day unless otherwise noted) 1. Statewide Fees Admission Range $1.00** - $10.00** (Does not include buses or admission to Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park or Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) Single-Occupant Vehicle or Motorcycle Admission $4.00 - $6.00** (Includes motorcycles with one or more riders and vehicles with one occupant) Per Vehicle Admission $5.00 - $10.00** (Allows admission for 2 to 8 people per vehicle; over 8 people requires additional per person fees) Pedestrians, Bicyclists, Per Passenger Exceeding 8 Per Vehicle; Per $2.00 - $5.00** Passenger In Vehicles With Holder of Annual Individual Entrance Pass Admission Economically Disadvantaged Admission One-half of base (Must be Florida resident admission fee** and currently participating in Food Stamp Program) Bus Tour Admission $2.00** per person (Does not include Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park, or $60.00 Skyway Fishing Pier State Park, or Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) whichever is less Honor Park Admission Per Vehicle $2.00 - $10.00** Pedestrians and Bicyclists $2.00 - $5.00** Sunset Admission $4.00 - $10.00** (Per vehicle, one hour before closing) Florida National Guard Admission One-half of base (Active members, spouses, and minor children; validation required) admission fee** Children, under 6 years of age Free (All parks) Annual Entrance Pass Fee Range $20.00 - $500.00 Individual Annual Entrance Pass $60.00 (Retired U. S. military, honorably discharged veterans, active-duty $45.00 U. S. military and reservists; validation required) Family Annual Entrance Pass $120.00 (maximum of 8 people in a group; only allows up to 2 people at Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park and Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) (Retired U. -

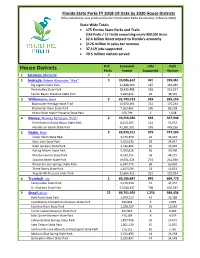

Florida State Parks Data by 2021 House District

30, Florida State Parks FY 2019-20 Data by 2021 House Districts This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation . FloridaStateParksFoundation.org Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.2 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $150 million in sales tax revenue • 31,810 jobs supported • 25 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 31,073,188 436 349,462 Big Lagoon State Park 10,336,536 145 110,254 Perdido Key State Park 17,191,206 241 198,276 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,545,446 50 40,932 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 26,651,285 416 362,492 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 18,971,114 266 218,287 Blackwater River State Park 7,101,563 99 78,680 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 578,608 51 65,525 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 41,626,278 583 469,477 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,558,966 106 83,636 Henderson Beach State Park 34,067,312 477 385,841 5 Drake, Brad 9 64,140,859 897 696,022 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 Deer Lake State Park 1,738,073 24 19,557 Eden Gardens State Park 3,235,182 45 36,128 Falling Waters State Park 5,510,029 77 58,866 Florida Caverns State Park 4,090,576 57 39,405 Grayton Beach State Park 17,072,108 239 186,686 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,911,495 97 78,277 Three Rivers State Park 2,916,005 41 30,637 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 19,533,681 273 213,693 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 45,103,015 632 504,860 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 St. -

30, House Districts

30, Florida State Parks FY 2018-19 Data by 2020 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, February 2020) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.6 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $176 million in sales tax revenue • 37,119 jobs supported • 29.5 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 35,086,662 491 399,461 Big Lagoon State Park 13,388,360 187 146,049 Perdido Key State Park 18,435,488 258 215,257 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,262,814 46 38,155 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,793,752 319 262,150 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,070,491 211 175,244 Blackwater River State Park 7,562,462 106 85,258 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 160,799 2 1,648 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 49,456,096 692 567,948 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 8,154,105 114 91,652 Henderson Beach State Park 41,301,991 578 476,296 5 Drake, Brad 9 69,939,012 979 747,560 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 Deer Lake State Park 2,102,533 29 24,057 Eden Gardens State Park 3,186,404 45 35,924 Falling Waters State Park 5,760,818 81 59,390 Florida Caverns State Park 4,532,155 63 44,215 Grayton Beach State Park 19,551,524 274 212,050 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,347,774 89 69,063 Three Rivers State Park 1,617,039 23 15,653 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 23,664,415 331 252,764 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 60,186,687 842 684,779 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 St. -

House Districts (This Compilation Was Produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019)

Florida State Parks FY 2017-18 Data by 2019 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, January 2019) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.4 billion direct economic impact • $158 million in sales tax revenue • 33,587 jobs supported • Over 28 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Hill, Walter Bryan “Mike” 0 2 Andre, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 28,135,146 393 338,807 Big Lagoon State Park 12,155,746 170 141,517 Perdido Key State Park 12,739,427 178 157,126 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,239,973 45 40,164 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,545,992 315 275,195 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,301,348 214 188,630 Blackwater River State Park 6,361,036 89 75,848 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 883,608 12 10,717 4 Ponder, Mel 2 46,877,022 657 564,936 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,896,093 111 88,633 Henderson Beach State Park 38,980,929 546 476,303 5 Drake, Brad 9 75,811,647 1062 881,589 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 Deer Lake State Park 1,654,544 23 19,939 Eden Gardens State Park 3,298,681 46 39,601 Falling Waters State Park 5,761,074 81 67,225 Florida Caverns State Park 12,217,659 171 135,677 Grayton Beach State Park 20,250,255 284 236,181 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 4,745,495 66 57,194 Three Rivers State Park 3,465,975 49 39,482 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 21,639,586 303 254,586 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 76,186,412 1,067 926,162 Camp Helen State Park 2,778,378 39 31,704 St. -

Choctawhatchee River & Bay SWIM Plan

Choctawhatchee River and Bay Surface Water Improvement and Management Plan November 2017 Program Development Series 17-05 NORTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT GOVERNING BOARD George Roberts Jerry Pate John Alter Chair, Panama City Vice Chair, Pensacola Secretary-Treasurer, Malone Gus Andrews Jon Costello Marc Dunbar DeFuniak Springs Tallahassee Tallahassee Ted Everett Nick Patronis Bo Spring Chipley Panama City Beach Port St. Joe Brett J. Cyphers Executive Director Headquarters 81 Water Management Drive Havana, Florida 32333-4712 (850) 539-5999 Crestview Econfina Milton 180 E. Redstone Avenue 6418 E. Highway 20 5453 Davisson Road Crestview, Florida 32539 Youngstown, FL 32466 Milton, FL 32583 (850) 683-5044 (850) 722-9919 (850) 626-3101 Choctawhatchee River and Bay SWIM Plan Northwest Florida Water Management District Acknowledgements This document was developed by the Northwest Florida Water Management District under the auspices of the Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) Program and in accordance with sections 373.451-459, Florida Statutes. The plan update was prepared under the supervision and oversight of Brett Cyphers, Executive Director and Carlos Herd, Director, Division of Resource Management. Funding support was provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund. The assistance and support of the NFWF is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to especially recognize members of the public, as well as agency reviewers and staff from the District and from the Ecology and Environment, Inc., team that contributed to the development of this plan. Among those that contributed considerable time and effort to assist in the development of this plan are the following. -

Florida's Coastal State Parks

The Economic Impact of Florida’s Coastal State Parks Florida Coastal State Parks Florida Keys and Coral Reef State Parks In 2019, Florida’s coastal state parks were visited In 2019, Florida’s keys and coral reef state parks were by more than 8 million visitors, who spent over visited by more than 3 million visitors, who spent over $570 million in local economies, supporting 10,196 jobs. $300 million in local economies, supporting 4,308 jobs. 2 13 1 4 3 5 6 Florida Water Management Districts Northwest Florida 14 11 Suwannee River 8 St. Johns River 7 Southwest Florida 12 South Florida 10 15 19 9 17 18 16 * Direct Economic Impact (DEI): The amount of new dollars spent in a local economy by non-local park visitors and park operations. Florida Coastal State Parks 1. Grayton Beach State Park 6. North Peninsula State Park 10. Gasparilla Island State Park (Walton County) (Volusia County) (Lee County) 212,050 park annual attendance 249,751 park annual attendance 281,241 park annual attendance $19.5 million DEI* $21.3 million DEI* $24.4 million DEI* 274 total jobs supported 299 total jobs supported 341 total jobs supported 2. Henderson Beach State Park 7. Sebastian Inlet State Park 11. Honeymoon Island State Park (Okaloosa County) (Brevard County) (Pinellas County) 476,296 park annual attendance 761,339 park annual attendance 1,610,871 park annual attendance $41.3 million DEI* $66.5 million DEI* $140.3 million DEI* 578 total jobs supported 931 total jobs supported 1,965 total jobs supported 3. -

Panhandle Birding Trail

The Great Florida Birding Trail is a project of the Florida Fish and Wildlife PANHANDLE FLORIDA Conservation Commission BIRDING TRAIL In partnership with : Wildlife Foundation of Florida U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Florida Park Service Florida Department of Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Many thanks to our generous sponsors : www.gulfpower.com The Great Florida Birding Trail www.nfwf.org www.FloridaBirdingTrail.com 05/06 Printed on recycled paper Getting Started... Ciity Locator Loaner optics are available free of charge at all Gateways, as well as at City Map City Map additional sites as marked in the site Apalachicola I Laguna Beach G descriptions! Bristol J Marianna F Carrabelle I Mexico Beach H Chattahoochee J Milton C Trail Tips Chipley F Panama City G When birding: Crawfordville M Pensacola B Crestview C Port St. Joe H • Take sunscreen, water and bug spray. De Funiak Springs E Quincy K • Make reservations in advance for "by-appointment Destin D Sopchoppy M only" sites. Ft. Walton Beach D St. Marks M • Check seasonality of site; are you visiting at the Grayton Beach D Sumatra I right time of year? Gulf Beach A Tallahassee L Gulf Breeze B Birder Vocabulary Some words used in this guide are specific to bird- How were these sites selected? ers and birdwatching. Bone-up on the following lingo Each of the sites in this guide was chosen for its bird- so you’ll blend in at your next birding dinner party! watching characteristics, accessibility and ability to Birding by ear: the ability to identify birds by their withstand birder use. -

A History of the Florida State Parks Foundation by Don Philpott

A H I S T O R Y O F T H E F L O R I D A S T A T E P A R K S F O U N D A T I O N B Y D O N P H I L P O T T A History of the Florida State Parks Foundation By Don Philpott 1 Contents Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................4 Tracing and preserving the Cracker Culture and all of Florida’s other cultures .....................................................4 Historical Perspective .............................................................................................................................................4 Friends of Florida State Parks (FFSP)/Florida State Parks Foundation (FSPF) Presidents ......................................7 Florida State Park Directors ....................................................................................................................................8 ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF THE FRIENDS OF FLORIDA STATE PARKS, INC. ................................................................8 In the beginning… .................................................................................................................................................... 10 The Florida Park Service, National Park Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps ........................................ 13 Everglades National Park and John D. Pennekamp Coral Reef Park ....................................................................... 39 1950s to 1990s ....................................................................................................................................................... -

1 Appendix 1C: the Status Of

APPENDIX 1C: THE STATUS OF SANDY, OCEANFRONT BEACH HABITAT IN THE COASTAL MIGRATION AND WINTERING RANGE OF THE PIPING PLOVER (Charadrius melodus)1 Tracy Monegan Rice Terwilliger Consulting, Inc. May 2012 The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS’s) 5-Year Review for the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) recommends developing a state-by-state atlas for wintering and migration habitat for the overlapping coastal migration and wintering ranges of the federally listed (endangered) Great Lakes, (threatened) Atlantic Coast and Northern Great Plains piping plover populations (USFWS 2009). The atlas should include data on the abundance, distribution and condition of currently existing habitat. This assessment addresses this recommendation by providing this data for one habitat type – sandy, oceanfront beaches within the migration and wintering range of the southeastern continental United States (U.S.). Sandy beaches are a valuable habitat for piping plovers, other shorebirds and waterbirds for foraging, loafing, and roosting. METHODS In order to evaluate the status of sandy, oceanfront beaches along the coastlines of North Carolina (NC), South Carolina (SC), Georgia (GA), Florida (FL), Alabama (AL), Mississippi (MS), Louisiana (LA) and Texas (TX), several methods were used. Non-sandy oceanfront areas were excluded since they do not currently provide this habitat; these areas occur along marshy sections of coast in Louisiana, the Big Bend Marsh coast of northwest Florida, the Ten Thousand Island Mangrove coast of southwest Florida, and the Florida Keys. The status of sandy, oceanfront beaches were evaluated through an estimation of the length and proportions of shoreline that were developed, undeveloped, preserved, armored and receiving beach fill or dredge spoil placement.