Irish Business Journal Case Study Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

451Research- a Highly Attractive Location

IRELAND A Highly Attractive Location for Hosting Digital Assets 360° Research Report SPECIAL REPORT OCTOBER 2013 451 RESEARCH: SPECIAL REPORT © 2013 451 RESEARCH, LLC AND/OR ITS AFFILIATES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ABOUT 451 RESEARCH 451 Research is a leading global analyst and data company focused on the business of enterprise IT innovation. Clients of the company — at end-user, service-provider, vendor and investor organizations — rely on 451 Research’s insight through a range of syndicated research and advisory services to support both strategic and tactical decision-making. ABOUT 451 ADVISORS 451 Advisors provides consulting services to enterprises, service providers and IT vendors, enabling them to successfully navigate the Digital Infrastructure evolution. There is a global sea change under way in IT. Digital infrastructure – the totality of datacenter facilities, IT assets, and service providers employed by enterprises to deliver business value – is being transformed. IT demand is skyrocketing, while tolerance for inefficiency is plummeting. Traditional lines between facilities and IT are blurring. The edge-to-core landscape is simultaneously erupting and being reshaped. Enterprises of all sizes need to adapt to remain competitive – and even to survive. Third-party service providers are playing an increasingly flexible and vital role, enabled by advancements in technology and the evolution of business models. IT vendors and service providers need to understand this changing landscape to remain relevant and capitalize on new opportunities. 451 Advisors addresses the gap between traditional research and management consulting through unique methodologies, proprietary tools, and a complementary base of independent analyst insight and data-driven market intelligence. 451 Research leverages a team of seasoned consulting professionals with the expertise and experience to address the strategic, planning and research challenges associated with the Digital Infrastructure evolution. -

British Journal of Nutrition (2011), 105, 1117–1132 Doi:10.1017/S0007114510004769 Q the Authors 2010

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (2011), 105, 1117–1132 doi:10.1017/S0007114510004769 q The Authors 2010 https://www.cambridge.org/core Short Communication Methodology for adding and amending glycaemic index values to a nutrition analysis package . IP address: 170.106.202.58 Sharon P. Levis1, Ciara A. McGowan2 and Fionnuala M. McAuliffe2* 1Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork, Republic of Ireland 2UCD Obstetrics and Gynaecology, School of Medicine and Medical Science, University College Dublin, National Maternity Hospital, Dublin 2, Republic of Ireland , on 01 Oct 2021 at 04:40:21 (Received 24 May 2010 – Revised 23 September 2010 – Accepted 19 October 2010 – First published online 9 December 2010) Abstract Since its introduction in 1981, the glycaemic index (GI) has been a useful tool for classifying the glycaemic effects of carbohydrate foods. , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at Consumption of a low-GI diet has been associated with a reduced risk of developing CVD, diabetes mellitus and certain cancers. WISP (Tinuviel Software, Llanfechell, Anglesey, UK) is a nutrition software package used for the analysis of food intake records and 24 h recalls. Within its database, WISP contains the GI values of foods based on the International Tables 2002. The aim of the present study is to describe in detail a methodology for adding and amending GI values to the WISP database in a clinical or research setting, using data from the updated International Tables 2008. Key words: Glycaemic index: Methodology: Food codes Carbohydrate-rich foods have been classified according to these values for each of the ten subjects is the final GI their induced glycaemic response since the 1970s(1 – 5). -

Section 177-AE Application Report Mahon Falls Car Park.Pdf

AN BORD PLEANÁLA SECTION 177AE APPLICATION FOR THE PROPOSED EXTENSION TO AN EXISTING MAHON FALLS CAR PARK & ADDITIONAL LAY BYS IN THE TOWNLAND OF COMERAGH MOUNTAIN, CO. WATERFORD. COMERAGH MOUNTAINS SAC (001952) temp March 2021 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... .2 1.2 Background ....................................................................................................................................... .2 2.0 PLANNING CONTEXT ................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Waterford County Development Plan 2011 – 2017 ............................................................... 5 2.1.1 6.1 (a) Policy with Regards to Areas Designed as Vulnerable ....................................... 5 2.1.2 6.2 (a) Policy with Regards to Areas Designated as Sensitive....................................... 5 2.1.3 Policy ENV3 ................................................................................................................ 6 2.1.4 Policy NH2 .................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.5 Policy NH6 .................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.6 -

Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 103, the Irish Bat Monitoring Programme

N A T I O N A L P A R K S A N D W I L D L I F E S ERVICE THE IRISH BAT MONITORING PROGRAMME 2015-2017 Tina Aughney, Niamh Roche and Steve Langton I R I S H W I L D L I F E M ANUAL S 103 Front cover, small photographs from top row: Coastal heath, Howth Head, Co. Dublin, Maurice Eakin; Red Squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Eddie Dunne, NPWS Image Library; Marsh Fritillary Euphydryas aurinia, Brian Nelson; Puffin Fratercula arctica, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; Long Range and Upper Lake, Killarney National Park, NPWS Image Library; Limestone pavement, Bricklieve Mountains, Co. Sligo, Andy Bleasdale; Meadow Saffron Colchicum autumnale, Lorcan Scott; Barn Owl Tyto alba, Mike Brown, NPWS Image Library; A deep water fly trap anemone Phelliactis sp., Yvonne Leahy; Violet Crystalwort Riccia huebeneriana, Robert Thompson. Main photograph: Soprano Pipistrelle Pipistrellus pygmaeus, Tina Aughney. The Irish Bat Monitoring Programme 2015-2017 Tina Aughney, Niamh Roche and Steve Langton Keywords: Bats, Monitoring, Indicators, Population trends, Survey methods. Citation: Aughney, T., Roche, N. & Langton, S. (2018) The Irish Bat Monitoring Programme 2015-2017. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 103. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Culture Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Ireland The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr Ferdia Marnell; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: David Tierney, Brian Nelson & Áine O Connor ISSN 1393 – 6670 An tSeirbhís Páirceanna Náisiúnta agus Fiadhúlra 2018 National Parks and Wildlife Service 2018 An Roinn Cultúir, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta, 90 Sráid an Rí Thuaidh, Margadh na Feirme, Baile Átha Cliath 7, D07N7CV Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 90 North King Street, Smithfield, Dublin 7, D07 N7CV Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Bunmahon Beach (2014)

Bathing Water Profile - Bunmahon Beach (2014) Bathing Water: Bunmahon Beach Bathing Water Code: IESEBWC050_0000_0200 Local Authority: Waterford County Council River Basin District: South Eastern Monitoring Point: 243400E, 98600N 1. Profile Details: Profile Id: BWPR00266 Toilets Available: No Year Of Profile: 2014 Car Parking Available: Yes Year Of Identification 1992 Disabled Access: Yes Version Number: 1 First Aid Available: Yes Sensitive Area: Yes Dogs Allowed: No Lifesaving Facilities: Yes Figure 1: Bathing Water 2. Bathing Water Details: Map 1: Bathing Water Location & Extent Bathing Water location and Bunmahon beach is located on the south coast of Ireland in county Waterford 25 km east of between extent: Dungarvan town. The beach is immediately west of the mouth of the River Mahon and it lies within the coastal body of the South East River Basin district. The designated bathing area is approximately 500 metres long and 100 metres wide (at low tide). Main features of the Bathing Type of Bathing Water: Bunmahon is a sandy beach with a gentle slope down to the low water mark and Water: variable slope below the low water mark. Currents can be very variable with sometimes challenging conditions for swimmers. The advice of lifeguards and locals should be asked for newcomers to the beach. Flora/Fauna, Riparian Zone: There is an interesting area of dunes on the road side of the beach with associated marine dune flora (plants) and fauna (animals). Above the cliffs areas of heath, improved grassland, unimproved wet and dry grassland, and woodland occur. On the beach low tide gives access to rock pools towards the western end of the beach which are home to a variety of plants and animals such as shrimp, crabs, small fish and anenomies. -

Expmlanatory Memorandum for the Quarterly Report

Irish Communications Market Quarterly Key Data Explanatory Memorandum Document No: 05/92a Date: 20th December 2005 An Coimisiún um Rialáil Cumarsáide Commission for Communications Regulation Abbey Court Irish Life Centre Lower Abbey Street Dublin 1 Ireland Telephone +353 1 804 9600 Fax +353 1 804 9680 Email [email protected] Web www.comreg.ie Contents Contents ..............................................................................................1 1 Executive Summary..........................................................................2 2 Questionnaire Issue ..........................................................................3 3 Primary Data ...................................................................................1 4 Secondary data ................................................................................5 4.1 PRICING DATA..........................................................................................5 4.2 COMPARATIVE DATA ...................................................................................6 5 Glossary..........................................................................................7 6 PPP Conversion Rates data ................................................................0 1 ComReg 05/92a 1 Executive Summary Following the publication of an annual market review in November 1999, ComReg’s predecessor- the ODTR- published its first Quarterly Review on 22nd March 2000. Since that date, ComReg has continued to collect primary statistical data from authorised operators on a quarterly -

2015 Study in Ireland Guide for Indian Students

Contact Us - Ireland: Education In Ireland Enterprise Ireland The Plaza East Point Business Park Study in Dublin 3 Ireland +353 1 7272359/ 7272967 India: Wendy Dsouza India Adviser Education in Ireland Enterprise Ireland Email: [email protected] Follow us on: @EduIreland www.facebook.com/EducationIrelandIndia www.educationinireland.com www.educationinireland.com Welcome To Introduction C O N T E N T S About Ireland 3 An English speaking country within the European Union, Ireland has a reputation for Studying In Ireland 7 natural beauty and friendliness. Ireland is home to more than 1,000 MNCs who run their Preparing For Your Irish Study Journey 11 back office operations out of the country and is just 9 hours by flight from India. Entry Into Ireland 15 Ireland has many similarities with India and Money Matters 17 an important one is that like India, Ireland is a young country with 34% of its population Settling Into Life In Ireland 19 under the age of 25 years. Staying Connected 21 Irish institutions offer a world class educational set up and offer a welcoming Access To Media Culture And Society 23 environment for Indian students. Getting Around 25 Why should you consider studying in Health Matters 29 Ireland? Working In Ireland 33 There are many reasons to consider studying in Ireland. The following are some of them. Safety Matters And The Law 36 World class institutions Returning Home 37 Extensive selection of courses High quality Universities and Technical Useful Links And Information 38 Institutions Friendly and welcoming environment Gateway into Europe Leading Global companies Technology hub Amazing art and culture scene Beautiful and scenic location 1 w w w. -

Life in the Fast Lane ONE of the Very First Community Broadband Schemes Is About to Be Switched on in Knockmore, Co Mayo

10 Digital Ireland March 2004 Broadband Ireland: Service providers BROADBAND BRIEFS No knocking Knockmore Life in the fast lane ONE of the very first community broadband schemes is about to be switched on in Knockmore, Co Mayo. The Knockmore initiative has set up a Community Network Society to bring affordable broadband By Leslie Faughnan broadband club had just biggest challenge to take up. access to the community on a non-profit basis. “We should be up 13,000 members. This year The blunt fact is that most and running in a few weeks with the first 30 or so households BROADBAND may be the the take-up speed has begun Irish business people have dominant technology topic of to accelerate at last with Ahern never personally experienced participating,” says chairman Paul Cunnane. Initial backhaul for the the day, but it’s still a fairly pointing out that there has the performance and advant- internet connection is expected to be based on a 2Mbps ADSL exclusive club that only passed been a 33pc weekly increase ages of always-on broadband. connection in Ballina relayed by wireless to the first node in the the 40,000-member mark a since broadband packages of It is confused with the simpler Knockmore region. Unlike broadcast wireless networking, needing at € few weeks ago. According to 40 per month were notions of ‘making internet least one high mast in line of sight, this project is based on a mesh introduced. Prices are contin- performance faster’ and the Minister for Commun- system where each access point is also a repeater linking to the next ications, Marine and Natural uing to inch downwards as perhaps unnecessarily fancy Resources, Dermot Ahern TD, resellers (and re-branders) of stuff such as multimedia and in a line of sight chain — neighbour passes on the signals to Ireland had a grand total of the Eircom service enter the streaming video. -

Consultation: 12/117

Internal Use Only ` Market Review Retail Access to the Public Telephone Network at a Fixed Location for Residential and Non Residential Customers All responses to this consultation should be clearly marked:- ―Reference: Submission re Market Review – Retail Access to the Public Telephone Network at a Fixed Location for Residential and Non Residential Customers, ComReg 12/117‖ and sent by post, facsimile, or e-mail, to arrive on or before 17:00 on 21 December 2012, to: Claire Kelly Commission for Communications Regulation Irish Life Centre Abbey Street Freepost Dublin 1 Ireland Ph: +353-1-8049600 Fax: +353-1-804 9680 Email: [email protected] Please note ComReg will publish all respondents‘ submissions with the Response to this Consultation, subject to the provisions of ComReg‘s guidelines on the treatment of confidential information – ComReg 05/24. Consultation and Draft Decision Reference: ComReg 12/117 Date: 26/10/2012 An Coimisiún um Rialáil Cumarsáide Commission for Communications Regulation Abbey Court Irish Life Centre Lower Abbey Street Dublin 1 Ireland Telephone +353 1 804 9600 Fax +353 1 804 9680 Email [email protected] Web www.comreg.ie Legal Disclaimer This Consultation Paper is not a binding legal document and also does not contain legal, commercial, financial, technical or other advice. The Commission for Communications Regulation (―ComReg‖) is not bound by it, nor does it necessarily set out ComReg‘s final or definitive position on particular matters. To the extent that there might be any inconsistency between the contents of this document and the due exercise by ComReg of its functions and powers, and the carrying out by it of its duties and the achievement of relevant objectives under law, such contents are without prejudice to the legal position of ComReg. -

2020 Ireland Virginmedia Fixed.Pdf

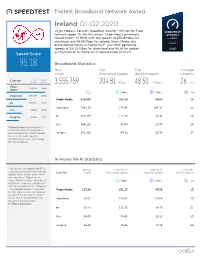

Fastest Broadband Network Award Ireland Q1-Q2 2020 Virgin Media is Ireland’s Speedtest Awards™ Winner for fixed network speed. To win this award, Virgin Media achieved a Speed Score™ of 95.18, with top speeds of 255.18 Mbps for download and 46.86 Mbps for upload. Virgin Media also achieved the fastest In-Home Wi-Fi with 90th percentile speeds of 251.23 Mbps for download and 45.36 for upload giving them an In-Home Wi-Fi Speed Score of 117.20. Speed Score 95.18 Broadband Statistics Test Top Top Average Count Download Speed: Upload Speed: Latency: Carrier User Speed Count Score 3,555,759 204.81 Mbps 48.50 Mbps 26 ms Virgin 174,762 95.18 Media Mbps Mbps ms Vodafone 138,085 48.82 Virgin Media 819,475 255.18 46.86 16 eir 163,255 39.59 Vodafone 768,153 175.95 135.14 22 Sky 43,985 36.53 eir 766,777 112.28 41.34 24 Imagine 28,895 29.78 Sky 194,226 95.33 29.73 25 Speed Score incorporates a measure of each provider’s download and upload speed Imagine 242,213 84.22 13.37 53 to rank network speed performance. See next page for more detail. In-Home Wi-Fi Statistics The fastest In-Home Wi-Fi is Speed Top Wi-Fi Top Wi-Fi Average calculated from the results of Carrier Score Download Speed Upload Speed Wi-Fi Latency speed tests taken over Wi-Fi connections. These tests come from various speedtest Mbps Mbps ms platforms and are combined into an overall Wi-Fi category. -

Volume 4 - Environmental Report

Waterford County Development Plan 2011-2017 Plean Forbartha Chontae Phort Láirge 2011-2017 Volume 4 - Environmental Report Waterford County Council STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT WATERFORD COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN REVIEW 2011 - 2017 February 2011 Waterford County Council Comhairle Chontae Port Láirge SEA Statement An Environmental Report was prepared by Waterford County Council on the potential significant environmental impacts of the Draft County Waterford Development Plan 2011-2017. Alternatives were considered for the future growth of the county that included continuing with existing amount of zoning in the County Development Plan 2005-2011 or reducing the area of zoned land in support of objectives in the Regional Planning Guidelines, Water Framework Directive and national energy policy. The preferred strategy was a reduction in zoned land to an area of 461 ha for residential development. Publication of the South East Regional Planning Guidelines 2010-2022 and provisions of the Planning Act 2000 (as amended) has stipulated the need for alignment of the Core Strategy with the Regional Planning Guidelines population thresholds and consequently a review of the Core Strategy contained in the Draft County Development Plan will commence in 2011. The Environmental Report highlighted key environmental pressures in the county that include water quality with the need to restore surface water quality in Dungarvan Bay, and Waterford Estuary, groundwaters around the River Suir, bathing waters in Ardmore and Dunmore East, continued monitoring of public water supplies and provision of sufficient capacity in waste water treatment plants and the Seven Villages Scheme. The need to maintain water quality is key to conservation of biodiversity and water dependant habitats and species. -

Broadband Telecommunications Benchmarking Study

Broadband Telecommunications Benchmarking Study January 2004 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary i 1.0. Background and Introduction 1 2.0. The Benchmarking Methodology 1 3.0. Telecommunications Sector Overview 1 4.0. Overall Benchmark Results 2 5.0. Sector-Specific Broadband Results 5 6.0. Drivers of DSL Roll-out and Take-up 8 7.0. Drivers of Fibre Optic Rollout and Take-up 11 8.0. Government Broadband Initiative 12 9.0. Demand for Broadband 12 Appendices Appendix 1: Glossary of Terms Used vii Appendix 2: Typical Business Use of Broadband viii Appendix 3: Summary of Broadband Access Technologies ix Appendix 4: Inter Platform Competition xii Broadband Benchmarking Paper Executive Summary I. Introduction This paper assesses Ireland’s competitiveness relative to 21 countries1 with a particular focus on the broadband2 telecommunications requirements of the enterprise sector. In recent months, there have been a number of positive developments in the telecommunications sector in Ireland, including: • The introduction of FRIACO3. Since June 2003, there has been strong growth in the number of flat rate narrowband subscribers and the number of households connected to the Internet. • There has been strong growth in DSL take-up4 as operators have temporarily reduced entry level prices and become more focused on marketing. • Construction of the Metropolitan Area Networks (MAN) is on schedule and expected to be operational by 2004. Selection of a Managed Services Entity (MSE) to operate these networks is at an advanced stage. Since the preparation of the statistics for this report, there have been a number of encouraging announcements by: 1.