Blue Crab Updated June 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RI Marine Fisheries Statutes and Regulations

Summary of Changes 8.1.9(I) Lobster and Cancer Crab pots: (A1) Maximum size: 22,950 cubic inches. (B2) Escape vents: Each and every lobster and Cancer crab pot, set, kept, or maintained or caused to be set, kept, or maintained in any of the waters in the jurisdiction of this State by any person properly licensed, shall contain an escape vent in accordance with the following specifications: (20-7-11(a)) (gvii) Lobster and Cancer crab traps not constructed entirely of wood must contain a ghost panel with the following specifications: 8.1.13(M) Commercial lobster trap tags: (A1) No person shall have on board a vessel or set, deploy, place, keep, maintain, lift, or raise; from, in, or upon the waters under the jurisdiction of the State of Rhode Island any lobster pot for taking of American lobster or Cancer crab without the pot having a valid State of Rhode Island lobster trap tag. (LN) For persons possessing a valid RI commercial fishing license (licensee) for the catching, taking, or landing of American lobster or Cancer Crab, and who also own or are incorporated/partnered in a vessel(s) holding a Federal Limited Access Lobster Permit (Federal Lobster Permit), the following shall apply: (1) No harvesting of lobsters or Cancer Crab may occur in any LCMA by means of any lobster trap for which a trap tag has not been issued. All vessels owned/incorporated/partnered by said licensee which hold a Federal Lobster Permit shall annually declare all LCMA(s) in which the licensee intends to fish during the fishery year. -

Impact of “Ghost Fishing“ Via Derelict Fishing Gear

2015 NOAA Marine Debris Program Report Impact of “Ghost Fishing“ via Derelict Fishing Gear 2015 MARINE DEBRIS GHOST FISHING REPORT March 2015 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science – Center for Coastal Environmental Health and Biomolecular Research 219 Ft. Johnson Rd. Charleston, South Carolina 29412 Office of Response and Restoration NOAA Marine Debris Program 1305 East-West Hwy, SSMC4, Room 10239 Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 Cover photo courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration For citation purposes, please use: NOAA Marine Debris Program. 2015 Report on the impacts of “ghost fishing” via derelict fishing gear. Silver Spring, MD. 25 pp For more information, please contact: NOAA Marine Debris Program Office of Response and Restoration National Ocean Service 1305 East West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 301-713-2989 Acknowledgements The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program would like to acknowledge Jennifer Maucher Fuquay (NOAA National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science) for conducting this research, and Courtney Arthur (NOAA National Ocean Service, Marine Debris Program) and Jason Paul Landrum (NOAA National Ocean Service, Marine Debris Program) for providing guidance and support throughout this process. Special thanks go to Ariana Sutton-Grier (NOAA National Ocean Science) and Peter Murphy (NOAA National Ocean Service, Marine Debris Program) for reviewing this paper and providing helpful comments. Special thanks also go to John Hayes (NOAA National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science) and Dianna Parker (NOAA National Ocean Science, Marine Debris Program) for a copy/edit review of this report and Leah L. -

Commercial Fishing Guide |

Texas Commercial Fishing regulations summary 2021 2022 SEPTEMBER 1, 2021 – AUGUST 31, 2022 Subject to updates by Texas Legislature or Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission TEXAS COMMERCIAL FISHING REGULATIONS SUMMARY This publication is a summary of current regulations that govern commercial fishing, meaning any activity involving taking or handling fresh or saltwater aquatic products for pay or for barter, sale or exchange. Recreational fishing regulations can be found at OutdoorAnnual.com or on the mobile app (download available at OutdoorAnnual.com). LIMITED-ENTRY AND BUYBACK PROGRAMS .......................................................................... 3 COMMERCIAL FISHERMAN LICENSE TYPES ........................................................................... 3 COMMERCIAL FISHING BOAT LICENSE TYPES ........................................................................ 6 BAIT DEALER LICENSE TYPES LICENCIAS PARA VENDER CARNADA .................................................................................... 7 WHOLESALE, RETAIL AND OTHER BUSINESS LICENSES AND PERMITS LICENCIAS Y PERMISOS COMERCIALES PARA NEGOCIOS MAYORISTAS Y MINORISTAS .......... 8 NONGAME FRESHWATER FISH (PERMIT) PERMISO PARA PESCADOS NO DEPORTIVOS EN AGUA DULCE ................................................ 12 BUYING AND SELLING AQUATIC PRODUCTS TAKEN FROM PUBLIC WATERS ............................. 13 FRESHWATER FISH ................................................................................................... 13 SALTWATER FISH ..................................................................................................... -

2021 Louisiana Recreational Fishing Regulations

2021 LOUISIANA RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS www.wlf.louisiana.gov 1 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO CONTENTS 6. LICENSING 9. DEFINITIONS DON’T 11. GENERAL FISHING INFORMATION General Regulations.............................................11 Saltwater/Freshwater Line...................................12 LITTER 13. FRESHWATER FISHING SPORTSMEN ARE REMINDED TO: General Information.............................................13 • Clean out truck beds and refrain from throwing Freshwater State Creel & Size Limits....................16 cigarette butts or other trash out of the car or watercraft. 18. SALTWATER FISHING • Carry a trash bag in your car or boat. General Information.............................................18 • Securely cover trash containers to prevent Saltwater State Creel & Size Limits.......................21 animals from spreading litter. 26. OTHER RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES Call the state’s “Litterbug Hotline” to report any Recreational Shrimping........................................26 potential littering violations including dumpsites Recreational Oystering.........................................27 and littering in public. Those convicted of littering Recreational Crabbing..........................................28 Recreational Crawfishing......................................29 face hefty fines and litter abatement work. -

Derelict Blue Crab Trap Removal Manual for Florida

DERELICT BLUE CRAB TRAP REMOVAL MANUAL FOR FLORIDA Prepared by Ocean Conservancy Based on Document Developed by Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Derelict Trap Task Force February 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................3 Introduction and Background...........................................................................................................4 Blue Crab Trap Fishery and Derelict Traps ...............................................................................4 Trap Retrieval Efforts ................................................................................................................4 Trap Retrieval Rules ........................................................................................................................8 Planning Derelict Blue Crap Trap Retrieval ..................................................................................12 Site Identification.....................................................................................................................12 Contact FWC Liaison ..............................................................................................................13 Appropriate Vessels .................................................................................................................13 Identify/Contact Local Partner Organizations..........................................................................14 Budget/Funding/Sponsorship...................................................................................................15 -

Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop

Special Report No. 75 of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop October 2002 Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop October 2002 Edited by Heather M. Stirratt Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Convened by: Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission August 26, 2002 Washington, DC Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop ii Preface This document was prepared in cooperation with the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s American Lobster Management Board, Technical Committee, Plan Development Team, Stock Assessment Subcommittee and the Advisory Panel. A report of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA17FG2205. Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop iii Acknowledgments This report is the result of a Workshop on transferable trap programs for American lobster which was held on August 26, 2002, in Washington, DC. The workshop was convened and organized by a Workshop Steering Committee composed of: David Spencer (Advisory Panel, Chair), George Doll (New York Commercial Lobsterman, Advisory Panel Member), John Sorlien (Rhode Island Commercial Lobsterman, Advisory Panel Member), Todd Jesse (Massachusetts Commercial Lobsterman, Advisory Panel Member), Ernie Beckwith (Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection), Mark Gibson (Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management), -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 159/Friday, August 16, 2019/Notices

41966 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 159 / Friday, August 16, 2019 / Notices Dated: August 13, 2019. • Instructions: Comments sent by any traps to target lionfish. Because FWC Tracey L. Thompson, other method, to any other address or requested that the amended EFP remove Acting Deputy Director, Office of Sustainable individual, or received after the end of the requirement that research traps have Fisheries, National Marine Fisheries Service. the comment period, may not be a current endorsement, stamp, or [FR Doc. 2019–17626 Filed 8–15–19; 8:45 am] considered by NMFS. All comments certification and allow sampling during BILLING CODE 3510–22–P received are a part of the public record the spiny lobster closed season, the EFP and will generally be posted for public would exempt research traps from the viewing on www.regulations.gov gear identification requirements at 50 DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE without change. All personal identifying CFR 622.402(a) and exempt the information (e.g., name, address), activities from the seasonal closures at National Oceanic and Atmospheric confidential business information, or 50 CFR 622.403. The amended EFP Administration otherwise sensitive information would also exempt the project activities RIN 0648–XS004 submitted voluntarily by the sender will from the closed seasons, size limits, and be publicly accessible. NMFS will bag limits at 50 CFR 622.34, 622.37, and Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of accept anonymous comments (enter ‘‘N/ 622.38 to allow FWC to retain other fish Mexico, and South Atlantic; Exempted A’’ in the required fields if you wish to for species identification verification Fishing Permits remain anonymous). -

Effect of Seismic Energy on Snow Crab (Chionoecetes Opilio)

Effect of Seismic Energy on Snow Crab (Chionoecetes opilio) By and For Environmental Studies Research Fund 444-7th Avenue S.W. Calgary, AB T2P 0X8 File No.: CAL-1-00364 7 November 2003 SA694 Effect of Seismic Energy on Snow Crab (Chionoecetes opilio) by John R. Christiana, Anne Mathieub, Denis H. Thomsonc, David Whiteb and Robert A. Buchanana a LGL Ltd., environmental research associates 388 Kenmount Rd., P.O. Box 13248, Stn. A, St. John’s, NL A1B 4A5 (709) 754-1992 bOceans Ltd. 31 Temperance Street St. John’s, NL A1C 3J3 (709) 753-5788 c LGL Ltd., environmental research associates 22 Fisher St., P.O. Box 280, King City, Ont. L7B 1A6 (905) 833-1244 for Environmental Studies Research Fund 444-7th Avenue S.W. Calgary, AB T2P 0X8 File No.: CAL-1-00364 7 November 2003 SA694 Effect of Seismic Energy on Snow Crab The correct citation for this report is: John R. Christian, Anne Mathieu, Denis H. Thomson, David White and Robert A. Buchanan Effect of Seismic Energy on Snow Crab (Chionoecetes opilio) 7 November 2003. Environmental Research Funds Report No. 144. Calgary. 106 p. The Environmental Studies Research Funds are financed from special levies on the oil and gas industry and administered by the National Energy Board for The Minister of Natural Resources Canada and The Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Environmental Studies Research Funds and any person acting on their behalf assume no liability arising from the use of the information contained in this document. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Environmental Studies Research Funds agencies. -

SEDAR7-DW-39 Florida Marine Research Institute Fishery Dependent Monitoring

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission SEDAR7-DW-39 Florida Marine Research Institute Fishery Dependent Monitoring Marine Information System • To conserve and manage Florida’s marine Fisheries • Established by Florida Statute (F.S.) Chapter 370 in 1983 • Requires wholesale dealers to report each purchase of saltwater products from licensed commercial fishers • Requires wholesale and retail dealers who produce (i.e., catch) saltwater products themselves to report amounts produced • Monthly reporting required (weekly for quota-managed species) • F.S. 370.07(6)(a) and Florid Administrative Code (FAC) 68E-5 specifies that records are to be kept by the dealers, the contents of these records, and reporting requirements Marine Fisheries Trip Ticket • Trip tickets are used to quantify commercial landings (pounds and value) of fish and shellfish. Annually, about 110 million pounds worth an estimated $190 million are reported on approximately 260,000 trip tickets. • Provides resource managers with a measure of fishing effort (trips) and trends in fisheries • Allows comparison of trip information (e.g., which species are caught, gears used on trips, participants in a fishery, levels of landings from trips). • Provides fishers with a record of sales of fish and invertebrates, and participation in fisheries • Four types of tickets: FWC issued, other approved dealer forms, oyster tally sheets, and digital records (see Attachments A1, A2) Trip ticket data collected • From 1985-1989, the marine fisheries trip ticket required the following information: Saltwater Products License (SPL; fisher license), dealer license, unloading date, time fished (usually time away from dock), county landed (where product came ashore), number of sets (nets, long lines), traps pulled (trap fisheries), soak time, species code, and amount of catch (usually in pounds). -

Mississippi Department of Marine Resources Part 4

TITLE 22 – MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF MARINE RESOURCES PART 4 RULES AND REGULATIONS FOR THE TAKING OF CRABS IN THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI Chapter 01 Introduction Purpose 100 This Part provides for the regulations of the commercial and recreational taking of crabs. Chapter 02 Justification and Authority 100 The Mississippi Commission on Marine Resources (MCMR) has determined that there is a continuing need for maintaining a sanctuary for sponge crabs. 101 There exists a need to prohibit the taking of crabs by unlicensed crab vessels. 102 In the case of licensed vessels fishing for crabs by means of crab traps or crab pots, that it is necessary for said traps or pots to be identifiable to enforcement personnel. 103 The MCMR is authorized to enact all regulations necessary for the protection, conservation or propagation of all seafood in the waters under the territorial jurisdiction of the State of Mississippi as provided for in § 49-15-15, of the Mississippi Code Ann. of 1972, as amended. Chapter 03 Possession Regulations 100 It is unlawful to catch, have or have in possession any female sponge crab or any female crab bearing visible eggs at any time. It is not unlawful to catch those crabs unintentionally, if the crabs are immediately returned to the water. 101 Any person, firm or corporation harvesting or possessing peeler or buster crabs which are under the five (5) inch minimum size requirement, must after removing the crabs from the traps or pots place them into a separate container. Undersize peeler or buster crabs are allowed in a single cull box (not to exceed 32” long by 19” wide by 12” high). -

Fishing Methods List

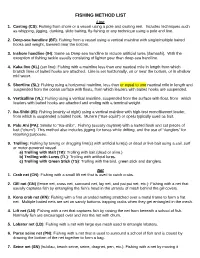

FISHING METHOD LIST Line 1. Casting (CS): Fishing from shore or a vessel using a pole and casting reel. Includes techniques such as whipping, jigging, dunking, slide baiting, fly-fishing or any technique using a pole and line. 2. Deep-sea handline (BF): Fishing from a vessel using a vertical mainline with single/multiple baited hooks and weight, lowered near the bottom. 3. Inshore handline (IH): Same as Deep-sea handline to include artificial lures (damashi). With the exception of fishing tackle usually consisting of lighter gear than deep-sea handline. 4. Kaka line (KL) (set line): Fishing with a mainline less than one nautical mile in length from which branch lines of baited hooks are attached. Line is set horizontally, on or near the bottom, or in shallow mid water. 5. Shortline (SL): Fishing using a horizontal mainline, less than or equal to one nautical mile in length and suspended from the ocean surface with floats, from which leaders with baited hooks are suspended. 6. Verticalline (VL): Fishing using a vertical mainline, suspended from the surface with float, from which leaders with baited hooks are attached and ending with a terminal weight. 7. Ika-Shibi (IS): Fishing (mainly at night) using a vertical mainline with high-test monofilament leader, from which is suspended a baited hook. Muhe’e (“true squid”) or opelu typically used as bait. 8. Palu Ahi (PA): Similar to “Ika-shibi”. Fishing (usually daytime) with a baited hook and cut pieces of bait (“chum”). This method also includes jigging for tunas while drifting, and the use of “danglers” for reporting purposes. -

Fixed Gear Guide: California, Oregon, and Washington Commercial Fisheries Trap/Pot, Gillnet, and Longline/Set Line

Fixed Gear Guide: California, Oregon, and Washington Commercial Fisheries Trap/pot, gillnet, and longline/set line Table of Contents Quick reference guide.................................................... 3 Introduction & Definitions............................................ 4 Gear configuration basics.............................................. 5 Buoys and Floats................................................................... 7 Special Buoy Markings........................................................... 8 Trap Key................................................................................. 9 Net Key................................................................................... 13 Gillnets .................................................................................. 14 Line....................................................................................................... 16 Fishery reference sheets Trap: California Nearshore Live Fish..............................18 Trap: Coonstripe Shrimp.................................................. 20 Trap: Dungeness Crab ..................................................... 22 Trap: Hagfish................................................................... 24 Trap: Rock Crab............................................................... 26 Trap: Sablefish................................................................. 28 Trap: Spiny Lobster.......................................................... 30 Trap: Spot Prawn............................................................