Counselors' Understanding of Process Addiction: a Blind Spot in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exercise Addiction – Cases, Possible Indicators and Open Questions

Review Sport & Exercise Medicine Switzerland, 68 (3), 54–58, 2020 Exercise addiction – cases, possible indicators and open questions Colledge Flora University of Basel Abstract Zusammenfassung While addictive disorders involving substances are well re- Substanzgebundene Suchterkrankungen sind gut recher- searched, the field of behavioral addictions, including exer- chiert; im Gegensatz dazu ist die Forschung hinsichtlich Ver- cise addiction, is in its infancy. Although exercise addiction haltenssüchte, unter anderem auch Bewegungssucht, noch is not yet recognized as a psychiatric disorder, evidence for nicht etabliert. Bewegungssucht wurde noch nicht als psychi- the burden it imposes has gained attention in the last decade. sche Störung eingestuft, die belastenden Symptome haben Characterised by a rigid exercise schedule, the prioritization allerdings in den letzten zehn Jahren viel Aufmerksamkeit of exercise over one’s own health, family and professional generiert. Die Symptome ähneln denjenigen von substanzge- life, and mental wellbeing, and extreme distress when exer- bundenen Süchten; ein rigides Konsummuster, die Vernach- cise is halted, the phenomenon shares many feature with sub- lässigung von Familie, Beruf und der eigenen Gesundheit, stance use disorders. While prevalence is thought to be low, und ein starkes psychisches Leid, wenn die Aktivität oder die affecting one in every 1000 exercisers, current research sug- Bewegung unterbrochen werden muss. Die Prävalenz ist ge- gests that the symptoms are extremely burdensome, and may mäss Einschätzungen gering; vermutlich ist jede tausendste often be accompanied by other psychiatric disorders. It is no sporttreibende Person betroffen. Jedoch sind die Symptome longer thought to be the case that only endurance athletes are für den Betroffenen schwerwiegend, und andere psychische at risk. -

Substance Use to Exercise: Are We Moving 3/17/2021 from One Addiction to Another?

Substance Use to Exercise: Are We Moving 3/17/2021 from One Addiction to Another? Wellness and Recovery in the Addiction Profession Part Two: Substance Use to Exercise: Are We Moving from One Addiction to Another? Presented by: Stephanie F. Rose, DSW, LCSW, AADC, CS and Duston Morris, PhD, MS, CHES 1 Jessica O’Brien, LCSW, CASAC Training Organizer • Training & Professional Development Content Manager • NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals • www.naadac.org • [email protected] 2 2 PRODUCED BY NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals 3 3 Presented by: Stephanie F. Rose, DSW, LCSW, AADC, CS and Duston Morris, PhD, MS, CHES 1 Substance Use to Exercise: Are We Moving 3/17/2021 from One Addiction to Another? www.naadac.org/certificate-for-wellness-and-recovery- online-training-series 4 4 4 www.naadac.org/substance-use-to-exercise-webinar CE Hours Available: 1.5 CEs CE Certificate : $25 If you complete all six parts in the series, you can apply for the Certificate of Achievement for Wellness & Recovery in the Addiction Profession 5 5 Using GoToWebinar (Live participants only) Control Panel Asking Questions Handouts Audio (phone option) Polling Questions 6 6 Presented by: Stephanie F. Rose, DSW, LCSW, AADC, CS and Duston Morris, PhD, MS, CHES 2 Substance Use to Exercise: Are We Moving 3/17/2021 from One Addiction to Another? Training Presenter • Duston Morris, PhD, MS, CHES • University of Central Arkansas 7 7 Training Presenter • Stephanie F. Rose, DSW, LCSW, AADC, CS • University of Central Arkansas 8 8 Substance Use to Exercise: Are We Moving From One Addiction to Another? STEPHANIE ROSE, DSW, LCSW, AADC, CS, DCC, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DUSTON MORRIS, PHD, MS, CHES, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 9 Presented by: Stephanie F. -

Process Addictions

Defining, Identifying and Treating Process Addictions PRESENTED BY SUSAN L. ANDERSON, LMHC, NCC, CSAT - C Definitions Process addictions – a group of disorders that are characterized by an inability to resist the urge to engage in a particular activity. Behavioral addiction is a form of addiction that involves a compulsion to repeatedly perform a rewarding non-drug-related behavior – sometimes called a natural reward – despite any negative consequences to the person's physical, mental, social, and/or financial well-being. Behavior persisting in spite of these consequences can be taken as a sign of addiction. Stein, D.J., Hollander, E., Rothbaum, B.O. (2009). Textbook of Anxiety Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishers. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) As of 2011 ASAM recognizes process addictions in its formal addiction definition: Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of pain reward, motivation, memory, and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social, and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addictive Personality? An addictive personality may be defined as a psychological setback that makes a person more susceptible to addictions. This can include anything from drug and alcohol abuse to pornography addiction, gambling addiction, Internet addiction, addiction to video games, overeating, exercise addiction, workaholism and even relationships with others (Mason, 2009). Experts describe the spectrum of behaviors designated as addictive in terms of five interrelated concepts which include: patterns habits compulsions impulse control disorders physiological addiction Such a person may switch from one addiction to another, or even sustain multiple overlapping addictions at different times (Holtzman, 2012). -

Pilot Study of Endurance Runners and Brain Responses Associated with Delay Discounting

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior: Papers & Publications Brain, Biology and Behavior, Center for 2017 Pilot Study of Endurance Runners and Brain Responses Associated with Delay Discounting Laura E. Martin University of Kansas Medical Center, [email protected] Jason-Flor V. Sisante Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science David R. Wilson Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science Angela A. Moody Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science Cary R. Savage Banner Health, [email protected] SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /digitalcommons.unl.edu/cbbbpapers Part of the Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons, Nervous System Commons, Other Analytical, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Techniques and Equipment Commons, Other Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons, Other Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons, and the Sports Sciences Commons Martin, Laura E.; Sisante, Jason-Flor V.; Wilson, David R.; Moody, Angela A.; Savage, Cary R.; and Billinger, Sandra A., "Pilot Study of Endurance Runners and Brain Responses Associated with Delay Discounting" (2017). Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior: Papers & Publications. 41. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cbbbpapers/41 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brain, Biology and Behavior, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior: Papers & Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Laura E. Martin, Jason-Flor V. Sisante, David R. Wilson, Angela A. Moody, Cary R. Savage, and Sandra A. Billinger This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ cbbbpapers/41 Original Research Pilot Study of Endurance Runners and Brain Responses Associated with Delay Discounting LAURA E. -

Exercise Pills for Drug Addiction

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Exercise Pills for Drug Addiction: Forced Moderate Endurance Exercise Inhibits Methamphetamine-Induced Hyperactivity through the Striatal Glutamatergic Signaling Pathway in Male Sprague Dawley Rats Suryun Jung , Youjeong Kim, Mingyu Kim , Minjae Seo, Suji Kim, Seungju Kim and Sooyeun Lee * College of Pharmacy, Keimyung University, 1095 Dalgubeoldaero, Dalseo-gu, Daegu 42601, Korea; [email protected] (S.J.); [email protected] (Y.K.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (S.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-53-580-6651; Fax: +82-53-580-5164 Abstract: Physical exercise reduces the extent, duration, and frequency of drug use in drug addicts during the drug initiation phase, as well as during prolonged addiction, withdrawal, and recurrence. However, information about exercise-induced neurobiological changes is limited. This study aimed to investigate the effects of forced moderate endurance exercise training on methamphetamine (METH)-induced behavior and the associated neurobiological changes. Male Sprague Dawley rats were subjected to the administration of METH (1 mg/kg/day, i.p.) and/or forced moderate endurance exercise (treadmill running, 21 m/min, 60 min/day) for 2 weeks. Over the two weeks, Citation: Jung, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; endurance exercise training significantly reduced METH-induced hyperactivity. METH and/or Seo, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. exercise treatment increased striatal dopamine (DA) levels, decreased p(Thr308)-Akt expression, Exercise Pills for Drug Addiction: and increased p(Tyr216)-GSK-3β expression. However, the phosphorylation levels of Ser9-GSK-3β Forced Moderate Endurance Exercise were significantly increased in the exercise group. -

Benefits & Downsides of Physical Activity Physical Activity Is

Benefits & Downsides of Physical Activity Physical Activity is Antidepressant & Addictive. Leroy Neiman, ‘Olympic Runner' Sept ‘10 - Jan ‘11 P.K. Diederix Master thesis Sept ‘10 - Feb ‘11 Master Neuroscience and Cognition, ECN-track Physical Exercise is Antidepressant & Addictive. Neuroscience and Pharmacology, Rudolf Magnus Institute, Utrecht University, the Netherlands P.K. Diederix 3157210 Supervisor Prof. Dr. L.J.M.J. Vanderschuren Second supervisor Dr. G. van der Plasse 1 Abstract Physical activity has been found generally as pleasant and good for one’s health. It is known to have a positive impact on nearly every system in the body. Regular exercise will improve the cardiovascular system, facilitates weight control, will create greater bone mineral density and it will decrease the risk for cancer, stroke and diabetes. Regular exercise can enhance and protect brain function and it has been found to have an antidepressant effect. Therefore physical activity is investigated to be used as a potential treatment for depression. It was found that physical activity can increase transmission of monoamines in the brain thereby correcting any imbalances seen in depressed patients. It also has an effect on the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis to reduce the effects of daily stressors which can be a cause of depression. In addition, it can increase the expression of BDNF in the hippocampus to facilitate neuronal growth and dendritic sprouting. Many other genes are activated important for regulating plasticity, metabolism, immune function and degeneration processes. Physical activity and anti-depressant drugs seem to have most prominent effect when used together. However, physical activity has traditionally been seen as having only positive influence for all people, but when taken to extremes, physical activity can become addictive and compulsive-like behaviour. -

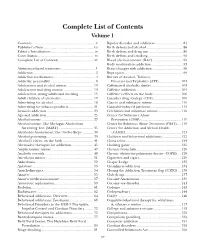

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents .....................................................................v Bipolar disorder and addiction .............................. 84 Publisher’s Note .......................................................vii Birth defects and alcohol ....................................... 86 Editor’s Introduction ............................................... ix Birth defects and drug use ..................................... 89 Contributors ............................................................. xi Birth defects and smoking ...................................... 90 Complete List of Contents ......................................xv Blood alcohol content (BAC) ................................ 92 Body modification addiction .................................. 93 Abstinence-based treatment ..................................... 1 Brain changes with addiction ................................. 96 Addiction ................................................................... 2 Bupropion ............................................................... 99 Addiction medications .............................................. 4 Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Addictive personality ................................................ 8 Firearms and Explosives (ATF) ....................... 101 Adolescents and alcohol misuse............................. 10 Caffeinated alcoholic drinks ................................ 103 Adolescents and drug misuse ................................. 13 Caffeine addiction ............................................... -

Naadac Wellness and Recovery in the Addiction

NAADAC WELLNESS AND RECOVERY IN THE ADDICTION PROFESSION PART THREE 2:00 PM – 3:00 PM CENTRAL MARCH 17, 2021 CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: CAPTIONACCESS [email protected] www.captionaccess.com >> Hi, everyone. And welcome to part three of six of the Specialty Online Training Series on Wellness and Recovery. Also happy St. Patrick's Day for those who celebrate. I wore my green. If not, happy March 17. And glad you are all here. Today's topic is Substance Use to Exercise - Are We Moving from One Addiction to Another? presented by Dr. Stephanie Rose and Dr. Duston Morris. My name is Jessica O’Brien and I am the training and professional developer content manager at NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals. And I am going to be the organizer of this training experience. This online training is produced by NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals. Closed caption the close captioning is provided by CaptionAccess so check your most recent confirmation e-mails or our Q&A box and checkbox for the link to use closed captioning today. Just so you know, every NAADAC online specialty series has its own webpage that houses everything you need to know about that particular series. If you missed a part of that series and decide to pursue the church certificate of achievement, you can take the training missed on-demand at wrong place, make the payment to quiz. You must be registered for any NAADAC training, live or recorded, in order to receive the certificate. So GoToWebinar provides us with a tool that tracking tool that for those who pass the CE quiz not only registered but watched the entire training. -

The Exercise Paradox: an Interactional Model for a Clearer Conceptualization of Exercise Addiction

Journal of Behavioral Addictions 2(4), pp. 199–208 (2013) DOI: 10.1556/JBA.2.2013.4.2 The exercise paradox: An interactional model for a clearer conceptualization of exercise addiction ALEXEI Y. EGOROV1,2,3 and ATTILA SZABO4,5* 1Department of Psychiatry and Addictions, Faculty of Medicine, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg, Russia 2Department of Psychiatry and Addictions, Mechnikov North-West Medical University, St. Petersburg, Russia 3Laboratory of Behaviour Neurophysiology, and Pathology, Sechenov Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry, St. Petersburg, Russia 4Institute for Health Promotion and Sport Sciences, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary 5Institutional Group on Addiction Research, Institute for Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary (Received: May 22, 2013; revised manuscript received: September 12, 2013; accepted: October 13, 2013) Background and aims: Exercise addiction receives substantial attention in the field of behavioral addictions. It is a unique form of addiction because in contrast to other addictive disorders it is carried out with major physical-effort and high energy expenditure. Methods: A critical literature review was performed. Results: The literature evaluation shows that most published accounts report the levels of risk for exercise addiction rather than actual cases or morbidi- ties. The inconsistent prevalence of exercise addiction, ranging from 0.3% to 77.0%, reported in the literature may be ascribed to incomplete conceptual models for the morbidity. Current explanations of exercise addiction may suggest that the disorder is progressive from healthy to unhealthy exercise pattern. This approach drives research into the wrong direction. Discussion: An interactional model is offered accounting for the adoption, maintenance, and trans- formation of exercise behavior. -

Long-Term Effect of Post-Traumatic Stress in Adolescence on Dendrite Development and H3k9me2/BDNF Expression in Male Rat Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex

fcell-08-00682 July 30, 2020 Time: 18:28 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 31 July 2020 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00682 Long-Term Effect of Post-traumatic Stress in Adolescence on Dendrite Development and H3K9me2/BDNF Expression in Male Rat Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex Mingyue Zhao, Wei Wang, Zhijun Jiang, Zemeng Zhu, Dexiang Liu and Fang Pan* Department of Medical Psychology and Medical Ethics, School of Basic Medicine Sciences, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China Edited by: Exposure to a harsh environment in early life increases in the risk of post-traumatic Fushun Wang, stress disorder (PTSD) of an individual. Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays Nanjing University of Chinese an important role in neurodevelopment in developmental stages. Both chronic and Medicine, China traumatic stresses induce a decrease in the level of BDNF and reduce neural plasticity, Reviewed by: Jung Goo Lee, which is linked to the pathogenesis of PTSD. Also, studies have shown that stress alters Inje University Haeundae Paik the epigenetic marker H3K9me2, which can bind to the promoter region of the Bdnf Hospital, South Korea Ruiyuan Guan, gene and reduce BDNF protein level. However, the long-term effects of traumatic stress Peking University, China during adolescence on H3K9me2, BDNF expression and dendrite development are not *Correspondence: well-known. The present study established a model of PTSD in adolescent rats using Fang Pan an inescapable foot shock (IFS) procedure. Anxiety-like behaviors, social interaction [email protected] behavior and memory function were assessed by the open field test, elevated plus maze Specialty section: test, three-chamber sociability test and Morris water maze test. -

Addictive Behaviors Reports 7 (2018) 26–31

Addictive Behaviors Reports 7 (2018) 26–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Addictive Behaviors Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/abrep Drug, nicotine, and alcohol use among exercisers: Does substance addiction ☆ ☆☆ T co-occur with exercise addiction? , ⁎ Attila Szaboa,b, , Mark D. Griffithsc, Rikke Aarhus Høglida, Zsolt Demetrovicsa a Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary b Institute of Health Promotion and Sport Sciences, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary c Department of Psychology, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Scholastic works suggest that those at risk for exercise addiction are also often addicted to illicit Alcohol drinking drugs, nicotine, and/or alcohol, but empirical evidence is lacking. Cigarette smoking Aims: The aim of the present work was to examine the co-occurrence of illicit drug, nicotine, and alcohol use Exercise dependence frequency (prevalence of users) and severity (level of problem in users) among exercisers classified at three levels Illicit substance use of risk for exercise addiction: (i) asymptomatic, (ii) symptomatic, and (iii) at-risk. Physical activity Methods: A sample of 538 regular exercisers were surveyed via the Qualtrics research platform. They completed Sport the (i) Drug Use Disorder Identification Test, (ii) Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, (iii) Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, and (iv) Exercise Addition Inventory. Results: A large proportion (n = 59; 10.97%) of the sample was found to be at risk for exercise addiction. The proportion of drug and alcohol users among these participants did not differ from the rest of the sample. However, the incidence of nicotine consumption was lowest among them. -

Exercise Dependence

Central Annals of Sports Medicine and Research Review Article *Corresponding author William F. Gayton, Department of Psychology, University of Southern Maine, Portland, Maine 04103, Exercise Dependence: The Dark USA, Tel: 207-780-4251; Email: Submitted: 19 July 2016 Accepted: 16 August 2016 Side of Exercise Published: 18 August 2016 ISSN: 2379-0571 William F. Gayton*, Andrew C. Loignon, and Will Porta Copyright Department of Psychology, University of Southern Maine, USA © 2016 Gayton et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS Along with the considerable health benefits regular exercise confers, it also Keywords carries inherent risk if pursued compulsively or to an extreme. Exercise addiction, also • Exercise often referred to as exercise dependence, remains a topic of study, but one without • Health risks a universally accepted definition. Researchers in the field have suggested utilizing the • Physical activity DSM criteria for Substance Use Disorder as they have found similar symptomatology in • Exercise dependence exercise addiction. This includes compulsion, withdrawal symptoms, and negative social consequences, as well as an array of unique health risks. An individual experiencing exercise addiction is much more likely to ignore signals from their body, such as pain and injury, and thus put themselves at risk of serious physical trauma. Sports medicine professionals are in a unique position to diagnose exercise dependence among the athletes they encounter in treatment. Once the diagnosis is made they must work to either avert full blown dependence, or assist those already further along in managing their symptoms and coming to grips with the addictive nature of their physical activity. This review provides an introduction to exercise dependence, as well as management and prevention recommendations for sports medicine professionals to utilize.