The Geoweb Slope Protection System Technical Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I/ General Description and Characterization of the NBS Entity

Objects/shapes/ physical projects > On the ground > system for erosion control “vegetation engineering systems for slope erosion control” STRONG SLOPE REVEGETATION (Steeper than 2:1) I/ General description and characterization of the NBS entity I.1 Definition and different variants existing Definition • Stabilizing soils structure on steepened slopes through revegetation in order to minimize or prevent the erosion of soil by wind or rain and landslides, avoiding sedimentation problems Smart slope-vegetated-retaining-wall, Dakota. Furbish 2013. © United Themes. When the slope is really steeped, the most common slope stabilization and erosion prevention method is some kind of retaining slopes method joined with revegetation. The origin of unstable slopes can be natural because of the soil geotechnical properties, or as consequence of human activities that create new cutting slopes or embankments during construction works. When soil is disturbed at a construction site, or the natural vegetation cover is retired, the erosion rate may increase significantly. Proper planning and use of erosion control prevention and mitigation measures can reduce the impact of human-caused erosion. In order to stabilize steepened slopes, some kind of soil retention method is nevertheless needed; joining it with a well-established vegetative cover is one of the most effective methods of reducing erosion in unstable slopes steeper than 2H:1V. The retention method keeps the soil meanwhile vegetation protects soil surfaces from rain generated splash erosion and can help to slow runoff flows across a disturbed ground. 1 / 11 In addition, plant roots hold their soil in place, keeping it from washing away during rainstorms. Lastly, trees help to prevent high winds from blowing away top soil because the trees provide windbreaks, which can prevent high winds. -

Alternative Bottom Liner System

Engineering Report: Appendix C Volume 2 Alternative Bottom Liner System COWLITZ COUNTY HEADQUARTERS LANDFILL PROJECT COWLITZ COUNTY, WASHINGTON Alternative Bottom Liner System COWLITZ COUNTY HEADQUARTERS LANDFILL PROJECT COWLITZ COUNTY, WASHINGTON Prepared for COWLITZ COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS November 2012 Prepared by Thiel Engineering P.O. Box 1010 Oregon House, CA 95962 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose and Scope ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Proposed Alternative ..................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Description of GCLs ...................................................................................................................... 3 2 TECHNICAL EQUIVALENCY AND PERFORMANCE ................................................. 5 2.1 The Theory of Composite Liners with Reference to GCLs ....................................................... 5 2.2 Technical Equivalency Issues ....................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Hydraulic Issues ........................................................................................................................... -

Interface Friction Performance

CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1.0 Introduction 1.1 PVC and HDPE 2.0 Testing Program 2.1 Materials 2.1.1 Geomembranes 2.1.2 Soil 2.1.2.1 Sand 2.1.2.2 Sandy Loam 2.1.2.3 Silty Clay 2.1.3 Geotextile 2.2 Equipment 2.3 Procedure 3.0 Results 3.1 Sand vs Smooth PVC 3.2 Sand vs the Other geomembranes 3.3 Influence of Soil type 3.4 Geomembrane vs Geotextile 4.0 Summary of Results 12 5.0 Discussion 5.1 Failure Modes 5.2 General Observations 5.3 Comparison with existing knowledge 6.0 Conclusions 2 1 References 2 1 APPENDIX A 23 APPENDIX B 29 APPENDIX C 35 APPENDIX D 41 FIGURES Typical cross-sections of modem landfills Schematic representation of stress-strain behaviour of HDPE & PVC Grain-size distribution of Sand, Sandy Loam and Silty clay Reproducibility of test data Sand vs Smooth PVC : Test results Sand vs Smooth HDPE Sandy Loam vs Smooth PVC Silty Clay vs Smooth PVC Non-woven Geotextile vs Smooth PVC Appendix A : Fine Sand vs various Geomembranes Al. Sand vs Smooth PVC A2. Sand vs Textured PVC A3. Sand vs File-finish PVC A4. Sand vs Smooth HDPE A5. Sand vs Textured HDPE Appendix B : Sandy Loam vs various Geomembranes B 1. Sandy Loam vs Smooth PVC B2. Sandy Loam vs Textured PVC B3. Sandy Loam vs File-finish PVC B4. Sandy Loam vs Smooth-HDPE B5. Sandy Loam vs Textured HDPE Appendix C : Silty Clay vs various Geomembranes C1. Silty Clay vs Smooth PVC C2. -

Guidance on the Design and Construction of Leak-Resistant Geomembrane Boots and Attachments to Structures

Guidance on the Design and Construction of Leak-Resistant Geomembrane Boots and Attachments to Structures R. Thiel, Vector Engineering, Grass Valley, CA, USA G. DeJarnett, Envirocon, Houston, TX, USA ABSTRACT Experience in reviewing, designing, performing field inspections, and installing of geomembrane boots and connections to structures has revealed a widely diverse practice of standards and approaches. The execution of these details is very much an art in workmanship, and depends a great deal on the experience and understanding of the installer. There is very little guidance in the literature regarding the fine points of specifying and installing these critical details. The typical manufacturers’ details and guidelines are not much more than concepts that have been repeated for two decades. Thus, there is a big difference between what we assume and expect versus what is constructed in terms of leak resistance of geomembrane penetrations and attachments to structures. The goal of this paper is to touch upon some of the detailed and critical aspects that should be addressed when specifying and constructing geomembrane seals around penetrating pipes (referred to as “boots”) and attachments to structures. 1. INTRODUCTION While much attention has been paid in the last 30 years to many other containment issues related to geomembranes (such as chemical compatibility, aging and durability, manufacturing, seaming, subgrade preparation, covering), there is surprisingly little technical discussion related to the design and construction of leak-resistant penetrations and attachments to structures. This subject has largely been relegated to a few simple details, mostly generated by the manufacturers and included in their standard literature. The content of this paper is derived from the authors’ field observations, experience, and deductive reasoning. -

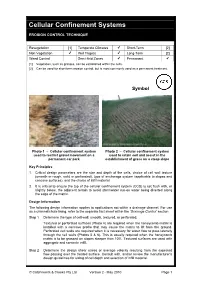

Cellular Confinement Systems

Cellular Confinement Systems EROSION CONTROL TECHNIQUE Revegetation [1] Temperate Climates ✔ Short-Term [2] Non Vegetation ✔ Wet Tropics ✔ Long-Term [2] Weed Control Semi-Arid Zones ✔ Permanent ✔ [1] Vegetation, such as grasses, can be established within the cells. [2] Can be used for short-term erosion control, but is most commonly used as a permanent treatment. Symbol Photo 1 – Cellular confinement system Photo 2 – Cellular confinement system used to restrict gravel movement on a used to retain soil and assist in the permanent car park establishment of grass on a steep slope Key Principles 1. Critical design parameters are the size and depth of the cells, choice of cell wall texture (smooth or rough, solid or perforated), type of anchorage system (applicable to slopes and concave surfaces), and the choice of infill material. 2. It is critical to ensure the top of the cellular confinement system (CCS) is set flush with, or slightly below, the adjacent terrain to avoid stormwater run-on water being diverted along the edge of the matrix. Design Information The following design information applies to applications not within a drainage channel. For use as a channel/chute lining, refer to the separate fact sheet within the ‘Drainage Control’ section. Step 1 Determine the type of cell wall: smooth, textured, or perforated. Textured or perforated surfaces (Photo 4) are required when the honeycomb matrix is installed with a concave profile that may cause the matrix to lift from the ground. Perforated cell walls are required when it is necessary for water flow to pass laterally through the cell walls (Photos 5 & 6). -

Geomembrane Puncture Potential and Hydraulic Performance in Mining Applications

GEOMEMBRANE PUNCTURE POTENTIAL AND HYDRAULIC PERFORMANCE IN MINING APPLICATIONS Lining systems in mining applications often consist of a geomembrane underlain by either a soil liner or a geosynthetic clay liner (GCL). When under load, geomembranes are vulnerable to damage from large stones both in the compacted soil subgrade and in the overlying drainage layer. Although guidance has been developed for minimizing geomembrane puncture, this past work has focused on subgrade protrusions in municipal solid waste applications. There has been limited information regarding puncture performance in mining applications, where extreme loads are encountered and angular, large-diameter crushed ore is often used as the drainage medium above the geomembrane. The attached paper discusses a laboratory puncture testing program involving various geomembranes placed in direct contact with different drainage media under high loads, both with and without underlying GCLs. Variables being examined include: geomembrane type and thickness, GCL type, normal load, and drainage stone size. Preliminary test results have shown that geomembrane/GCL composite liners are subject to less puncture damage (i.e., lower defect frequency and/or smaller puncture sizes) than geomembrane liners alone. The paper also presents a feasibility study of two lining alternatives, geomembrane/compacted soil and geomembrane/GCL composites. The feasibility study compares technical effectiveness and cost effectiveness based on cost savings associated with improved metal recovery rates afforded by improved containment. This information is intended for mining companies and engineers in evaluating lining options and allowable stone sizes. This paper was presented at the Tailings and Mine Waste ’08 Conference. TR 260 11/08 800.527.9948 Fax 847.577.5566 For the most up-to-date product information, please visit our website, www.cetco.com. -

Geomembrane Lifetime Prediction: Geosynthetic Institute

Geosynthetic Institute GRI 475 Kedron Avenue GEI GII Folsom, PA 19033-1208 USA GSI TEL (610) 522-8440 FAX (610) 522-8441 GAI GCI GRI White Paper #6 - on - Geomembrane Lifetime Prediction: Unexposed and Exposed Conditions by Robert M. Koerner, Y. Grace Hsuan and George R. Koerner Geosynthetic Institute 475 Kedron Avenue Folsom, PA 19033 USA Phone (610) 522-8440 Fax (610) 522-8441 E-mails: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Original: June 7, 2005 Updated: February 8, 2011 Geomembrane Lifetime Prediction: Unexposed and Exposed Conditions 1.0 Introduction Without any hesitation the most frequently asked question we have had over the past thirty years’ is “how long will a particular geomembrane last”.* The two-part answer to the question, largely depends on whether the geomembrane is covered in a timely manner or left exposed to the site-specific environment. Before starting, however, recognize that the answer to either covered or exposed geomembrane lifetime prediction is neither easy, nor quick, to obtain. Further complicating the answer is the fact that all geomembranes are formulated materials consisting of (at the minimum), (i) the resin from which the name derives, (ii) carbon black or colorants, (iii) short-term processing stabilizers, and (iv) long-term antioxidants. If the formulation changes (particularly the additives), the predicted lifetime will also change. See Table 1 for the most common types of geomembranes and their approximate formulations. Table 1 - Types of commonly used geomembranes -

Water Content–Density Criteria for Determining Geomembrane–Fly Ash Interface Shear Strength

MATEC Web of Conferences 262, 04005 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201926204005 KRYNICA 2018 Water Content–Density Criteria for Determining Geomembrane–Fly Ash Interface Shear Strength Katarzyna Zabielska-Adamska1,* 1 Bialystok Technical University, Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Wiejska Street 45E, 15-351 Bialystok, Poland Abstract. The aim of the present paper was to determine shear strength at the interface between fly ash, as a material underlying artificial sealing layer of storage yards, and HDPE geomembranes. The fly ash was compacted at moisture contents ranging over optimum water contents ± 5% using the standard Proctor test. The shear strength and interaction tests were conducted in classic direct shear apparatus with a cylindrical shear box. For interface strength tests the bottom box frame was equipped with a polycarbonate platen, which enabled geomembrane fixing. The shear strength of the interface contact of fly ash–smooth HDPE geomembrane did not greatly depend on moisture at compaction; however, it was important for textured geomembrane. The lowest interface strength was obtained at the highest moisture w= wopt + 5%, and the greatest values at moistures w ≥ wopt, for both geomembranes. 1 Introduction of compacted non-cohesive fly ash and fly ash/bottom ash mixture are dependent on moisture content during Mineral soil liners and covers are most often single, compaction, w, as are properties of cohesive mineral double or multilayer complex sealing, consisting of soils [14]. Consequently, different values are obtained compacted cohesive soil layers, with coefficient of for w on either side of the wopt on a compaction curve, –9 permeability, k, lower than 10 m/s, characterised by a for the same dry densities, ρd. -

Geomembranes and Seams

Geomembranes and Seams Ian D. Peggs I-CORP INTERNATIONAL, Inc., USA [email protected] ABSTRACT: Geomembranes and their seams have been destructively tested the same way for many years. However, it is still not appreciated that only shear elongation and peel separation provide useful information on weld integrity. It would be desirable to preclude seam destructive testing and to replace it with nondestructive testing (NDT) methods. Electrical methods are now available for locating leaks anywhere in liners whether covered or exposed. On landfill caps infrared spectroscopy can locate leaks much faster. Unfortunately, these methods will not assess the bond efficiency of a weld. However, ultrasonic (UT) methods, both pulse-echo and pitch-catch techniques are being developed to evaluate bond quality and the presence of internal flaws that may become leaks in service. The most promising method for the NDT evaluation of seam bond strength is infrared thermography (IRT) that even appears capable of identifying variations in weld zone microstructure due to cycling of the welder wedge temperature. 1 INTRODUCTION Geomembrane seams have been nondestructively and destructively tested the same way for many years. Only the acceptance criteria for destructively tested samples have been updated, but not far enough. However, seams are only a very small fraction of the total area of the liner which, until the development of electrical methods, could only be monitored visually It is past time that these test methods were reviewed and updated to take advantage of new technologies and the statistics generated over many years of testing. If this is not done we are wasting much time and are not achieving the highest quality lining systems. -

GEOMEMBRANE OR GEOSYNTHETIC CLAY LINER Code 521A (Ft2)

PA521-1 CONSERVATION PRACTICE STANDARD POND SEALING OR LINING - GEOMEMBRANE OR GEOSYNTHETIC CLAY LINER Code 521A (Ft2) DEFINITION A liner for an impoundment constructed using a geomembrane or a geosynthetic clay material. PURPOSE This practice is to: Reduce seepage losses from an impoundment for water conservation. Protect soil and water from contaminants. CONDITIONS WHERE PRACTICE APPLIES This practice applies where in-place natural soils have excessive seepage rates. CRITERIA General Criteria Applicable to Purposes. Design. The structure to be lined must meet all applicable NRCS standards. All inlets, outlets, ramps, and other appurtenances may be installed before, during, or after the liner placement, but must be done in a manner that does not damage or impair the proper operation of the liner. Flexible membrane liners must be planned, designed, and installed in conformance with all applicable federal, state, and local laws and regulations. Design and install the liner in accordance with manufacturer recommendations. The installer or manufacturer must certify that the liner installation meets the material and installation requirements of the plans and specifications. Follow manufacturer’s recommendations with regard to protection from weather and ultraviolet exposure. Materials. Geomembrane materials must meet the criteria in NRCS National Engineering Handbook (NEH), Part 642, Chapter 3, “Material Specification 594 – Geomembrane Liner.” GCL materials must meet the criteria in NRCS NEH, Part 642, Chapter 3, “Material Specification -

Technical Specifications, Special Provisions and Supplemental Terms and Conditions HALDEMAN CREEK WEIR REPLACEMENT

Technical Specifications, Special Provisions and Supplemental Terms and Conditions For HALDEMAN CREEK WEIR REPLACEMENT Collier Co. Project No.: 60103 Collier Co. Work Order No.: 4500158645 Atkins Project No.: 100045545 Date: October 20, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS ..........................................................1 ADDITIONAL TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS ..................................................................... 2 SECTION 101 - MOBILIZATION ..............................................................................3 SECTION 110 - CLEARING AND GRUBBING ......................................................6 SECTION 120-SPECIAL – DITCH FINISH GRADING .........................................7 SECTION 400.1-SPECIAL – DEWATERING .........................................................8 SECTION 425 - INLETS, MANHOLES, AND JUNCTION BOXES .....................9 SECTION 515 – PEDESTRIAN/BICYLE RAILINGS, GUIDERAILS, AND HANDRAILS ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 570 - PERFORMANCE TURF .............................................................13 SECTION CF-SPECIAL – COCONUT FIBER EROSION CONTROL FABRIC ...........................................................................................................14 SECTION ELEC-SPECIAL – ELECTRICAL WORK ...........................................18 SECTION GATE-SPECIAL – HINGED CREST GATES ....................................24 SECTION GW-SPECIAL – GEOWEB STABILIZATION ....................................36 -

Triple Crown Line Development Inc

Triple Crown Line Development Inc. Revised Slope Stability Analysis Triple Crown Line Residential Development Airport Road and Cranston Drive City of Caledon East, Ontario Project Number BRM-00235186-G0 Prepared By: EXP Services Inc. 56 Clark Boulevard Brampton, Ontario, Canada L6T 4V1 Date Submitted September 11, 2018 Slope Stability Analysis Update BRM-00235186-G0 Triple Crown Line Residential Development Caledon East, Ontario TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 2 Site Visit 4 3 Slope Conditions 5 4 Subsurface Conditions 6 4.1 Subsoil ................................................................................................................. 6 4.1.1 Section 2 (Borehole 14) ............................................................................ 6 4.1.2 Section 9 (Borehole 61) ............................................................................ 7 4.1.3 Section 10 (Borehole 62) .......................................................................... 8 4.1.4 Section 12 (Boreholes 64 and 65) ............................................................ 9 5 General Slope Stability Analyses 11 5.1 Methodology ...................................................................................................... 11 5.2 Results of Stability Analyses .............................................................................. 13 5.2.1 Section 2 (Figures 1 and 2) .................................................................... 13 5.2.2 Section 9 (Figures 3 and 4) ...................................................................