Pruning Cuts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 6 Care and Handling

Chapter 6 Care and Handling The following TEKS will be addressed in this chapter: (6) The student knows the management factors of floral enterprises. The student is expected to: (A) use temperature, preservatives, and cutting techniques to increase keeping quality; (B) identify tools, chemicals, and equipment used in floral design; (C) fertilize, prune, and water tropical plants; (D) manage pests; and (E) demonstrate the technical skills for increasing the preservation of cut flowers and foliage. Care and Handling of Cut Flowers and Foliages Cut flowers, even though they have been separated from the parent plant, are living, actively metabolizing plant parts. These parts undergo the same basic aging process as the entire plant — only quicker. However, the rate of deterioration can be slowed down considerably by supplying the cut flower with its basic needs. The first and foremost need of a cut flower is water. Second is food. In addition, certain damaging factors such as exposure to ethylene gas, microbial attack and rough handling must be avoided. From a practical point of view, a controlled rate of opening is needed as well as maintenance of good color. All of these factors must be considered by everyone who handles the product. This includes growers wholesalers and retailers. In order to be competitive in the marketplace our product must be desirable to the consumer. Our flowers must be fresh for the customer to enjoy! Factors Affecting Quality There are several factors which play a part in keeping the quality of cut flowers at a high level: (1) the grower (2) moisture balance. -

CHERRY Training Systems

PNW 667 CHERRY training systems L. Long, G. Lang, S. Musacchi, M. Whiting A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY n WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY n UNIVERSITY OF IDAHO in cooperation with MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY CHERRY training systems Contents Understanding the Natural Tree....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Training System Options.......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Rootstock Options.......................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Pruning and Training Techniques.....................................................................................................................................................5 Kym Green Bush............................................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Spanish Bush.....................................................................................................................................................................................................18 Steep Leader......................................................................................................................................................................................................25 -

Dormant Tree (And Shrub) Pruning

Dormant Tree (and Shrub) Pruning By Sue Gwise, Consumer Horticulture Educator & Master Gardener Coordinator If you need to prune any of your hardwood trees, late winter is the best time for this task. Even fruit trees like apple, pear, and peach should be pruned during the dormant season, which is basically February through early April, and prior to spring bud swell. The worst time to prune hardwood trees is during or soon after their initial growth flush. Unfortunately, this is the same time of year when most people begin their landscape chores. A prune at this point is very stressful to the tree. Dormant pruning is done for several reasons: 1. Fungi and insects are not active, and this eliminates the chance of disease and infestation. 2. Pruning done before bud swell in early spring will maximize growth. 3. It minimizes the chance of cold damage which is higher if pruning is done in early winter. 4. The tree will go into a full season of active growth in which pruning wounds will close-up much quicker. 5. There are no leaves, so it is much easier to see the tree structure. Like anything, there are exceptions. Crabapples, for example, tend to sucker profusely if pruned in the winter or early spring. As a result, species prone to suckering should be pruned in the summer. Things get trickier with ornamental flowering trees and shrubs. In these cases, the timing of pruning relates to the type of wood that develops flowers. In species where blooms occur on the current season’s growth (new wood), a dormant pruning is fine. -

Developing a PREVENTIVE PRUNING PROGRAM in Your Community: Mature TREES

CHAPTER DEvElopinG A pREvEnTIVE pRUNING pRoGRAM in yoUR coMMUniTy: mature TREES PUBLICATION Nº ENH 1063 e d w a r d f. g i l m a n a m a n d a b i s s o n Introduction A preventive pruning program should be designed to create structurally sound trunk and branch architecture that will W\QZcRSRPO`Y sustain a tree for a long time. The goal Q]R][W\O\babS[a with mature trees is to develop and maintain a sound structure to minimize RSORP`O\QV hazards such as branch failure. This task is easier provided a good structure was eObS`a^`]cba established earlier in the tree’s life. When properly executed, a variety of benefits are derived from pruning. Benefits include reduced risk of branch P`]YS\P`O\QV and stem breakage, better clearance for vehicles and pedestrians, improved health and appearance, and enhanced view. When improperly performed, pruning can harm a tree’s health, stability, acQYS` and appearance. Several consequences occur when pruning is not performed q at all (Figure 1). These consequences include development of low limbs; weak, codominant stems; defects such Figure q as included bark; and accumulation of Problems that can develop on trees include codominant dead branches. Formation of codominant stems, included bark, broken and dead branches and large stems and defects such as included bark removed limbs that result in trunk decay. can lead to increased risk of breakage. The Urban Forest Hurricane Recovery Program http://treesandhurricanes.ifas.ufl.edu One of the most common defects in Figure planted trees is formation of large, w low limbs. -

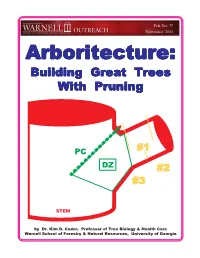

Pruning Manual Arboritecture

Pub. No. 37 November 2016 Arboritecture:Arboritecture: BuildingBuilding GreatGreat TreesTrees WithWith PruningPruning ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 #1○○○○○○○ 1234567890123456789012345 #1 1234567890123456789012345PC 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345DZ 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 #2 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345#3 1234567890123456789012345 1234567890123456789012345 STEM by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia This manual is a third revision of a popular educational product designed for helping tree health care providers and other allied professionals appreciate and understand a number of basic aspects of young to middle-aged tree pruning. This manual is a synthesis and integration of research and educa- tional concepts regarding trees and how pruning impacts tree biology, struc- ture and aesthetics. This product is for awareness building and educational development. This product does not represent young tree training specifica- tions or pruning standards. At the time it was finished, this publication -

What Makes a Tree

Trees 101 Structure, Function, Identification, Jargon Pam Zipse Outreach Coordinator, Rutgers Urban Forestry Program of NJAES urbanforestry.rutgers.edu NJ Licensed Tree Expert # 426 NJ Certified Teacher of Biological Science # 863775 Defining a Tree What is a Tree? • A woody perennial plant, typically having a single stem or trunk growing to a considerable height and bearing lateral branches at some distance from the ground. What is a Tree? • A large water pump facilitating moisture exchange for energy conversion and food production. Photosynthesis Photosynthesis • For a tree to be healthy, it must be able to carry out photosynthesis. • Carbon Dioxide + Water in the presence of light , yields Sugar + Oxygen LIGHT CO₂ + H₂O → C₆H₁₂O₆ + O₂ Photosynthesis • So what does a tree need to be able to successfully carry out photosynthesis? • Carbon Dioxide (Air) • Water • Light Photosynthesis • Anything that inhibits a tree’s ability to carry out photosynthesis… • Anything that prevents a tree from pumping water and cycling air… • is going to harm the tree! Forestry is Common Sense Elevated to a Science Structure and Function… Beginners Guide to Tree Anatomy and Physiology Anatomy & Physiology (Structure & Function) • Tree Anatomy deals with the structure of trees. – What are the parts of a tree? • Tree Physiology deals with the functions and activities of these parts. – How does a tree grow? How does a tree grow? How does a tree grow? • Trees grow from the outside out and from the top up. How does a tree grow? • The cambium is the living layer of actively dividing cells located just inside the bark that produces a new growth ring each year. -

Merritt College Landscape Horticulture Degree & Certificate

1 Merritt College Landscape Horticulture Degree & Certificate Options 2019-2021 Merritt College Landscape Horticulture now has a new Arboricul- Program Learning Outcomes: ture program offering two Certificates of Achievement & an Associate Students who complete the certificate will be able to: of Science degree. This program was designed with input from local tree • Create & maintain landscapes that provide basic human comfort and livability industry employers, and those employers are looking to hire our grads! • Create and maintain landscapes that respect and respond to regional ecology, including plant community dynamics, soil mediums, water and moisture Merritt College is home to one of the largest horticulture facilities in requirements, and sustainable potential in Bay Area environments northern California. Our 7.5-acre facility includes 10k sq. ft. of greenhouse • Communicate basic horticulture concepts to clients, contractors, public agencies. and lath house space; drafting & floral design labs; and the Emile Labadie Arboretum. Students on an associate degree track will be able to complete Certificate of Achievement Requirements: all required coursework within a two-year period, but students are free to LH 1 (day) OR 1E (eve) Intro to LANHT 3 units work at their own pace. Merritt Landscape Horticulture is a Career Education LH 23 Plant Terminology 2.5 units program, and our programs are designed to equip students with the knowledge and LH 26 Pruning .5 units experience needed to be job-ready, and to enhance/refresh the skills of those One 3 unit plant ID course: already working in the field. LH 2 or 2E; 3 or3E; 4 or 4E; 5 A, EA, B or EB; 6A, EA, B or EB; 7 or 7E; 40 or 40E 3 units One course from following: One or more certificates or degrees in Landscape Horticulture will be LH 13 (day) OR 13E eve Arboriculture 3 units awarded upon satisfactory completion of the program requirements. -

Pruning the Orchard

Pruning the Orchard Ronald H. Walser, Wilford A. Wright, Alvin R. Hamson, Extension Horticulturists, Utah State University Revised March 1994 by Dan Drost, Extension Vegetable Specialist, and Tony Hatch, Extension Horticulture Specialist March 1994 HG 363 CONTENTS Introduction ....................................... 1 Pruning Equipment .................................. 1 Apple Trees ....................................... 1 Central Leader Pruning .............................. 2 Modified Leader or Modified Central Leader Pruning ...... 3 Peach and Nectarine ................................. 5 Open Center Pruning ................................ 6 Pear Trees ......................................... 7 Sweet Cherry Trees ................................. 8 Tart Cherry Trees ................................... 8 Plums ............................................ 9 Apricot Trees ...................................... 9 Walnut and Pecan Trees ............................. 10 Espalier .......................................... 10 Pruning Neglected Trees ............................ 11 Grapes .......................................... 12 Raspberries ....................................... 13 Red Raspberries ................................... 14 Everbearing Raspberries ............................ 15 Blackberries ...................................... 15 Currants and Gooseberries ........................... 15 Glossary ......................................... 16 General Rules for Pruning ........................... 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The authors -

Tree Identification ISA Certified Arborist

Panelists: (comprised of urban foresters and certified arborists) • John Warner, Texas A&M Forest Service, Facilitator • Jordy Herrin, Texas A&M Forest Service, Chat box monitor • Mark Kroeze, Texas A&M Forest Service • Jack Hill, Burditt Consultants, LLC • Michael Gabrielse, Burditt Consultants, LLC What we will cover today in All About Trees Tree Pruning: Why prune, pruning types, pruning guidelines, wound wood, codominant stems, bad pruning habits, physiological characteristics of trees Tree Planting: Proper planting, when to plant, planting stock Tree Facts & Quiz Tree Root Architecture Small absorbing roots Lateral roots Sinker roots Taproot = Topping a tree is considered a healthy way of pruning. True or False? False! Topping, de- horning, hat-racking or what ever you want to call it is NOT recognized by any of the professional arboriculture organizations, urban forestry professionals or certified arborists as an approved method of pruning. Pruning Trees Proper pruning helps keep plants’ attractive and vigorous and will add years to the plant’s health. Many people are apprehensive about pruning, but knowing how, when and why to prune will end these fears. Basic Pruning Questions May include but are not limited to: – Three D’s – Dead, Dying or Diseased – Improve Tree Structure & Form – Crowded – Reducing risk – Potential hazards – Improving aesthetics – Satisfying a specific need Basic Pruning Guidelines •Prune first for safety, next for health, and finally for aesthetics. •Never prune trees that are touching or near utility lines; instead consult your local utility company. •Always have a reason for pruning •TREES DO NOT HEAL THEY SEAL Basic Pruning Guidelines • Remove broken or hanging limbs immediately before they fall. -

Tree Pruning: the Basics! Pruning Objectives!

1/12/15! Tree Pruning: The Basics! Pruning Objectives! Improve Plant Health! Safety! Aesthetics! Bess Bronstein! [email protected] Direct Growth! Pruning Trees Increase Flowers & Fruit! Remember-! Leaf, Bud & Branch Arrangement! ! Plants have a genetically predetermined size. Pruning cant solve all problems. So, plant the right plant in the right way in the right place.! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees 1! 1/12/15! One year old MADCap Horse, Ole!! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Internode Maple! Ash! Horsechestnut! Dogwood! Oleaceae! Node Caprifoliaceae! Most plants found in these genera and families have opposite leaf, bud and branch arrangement.! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees One year old Node & Internode! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Internode Node! • Buds, leaves and branches arise here! Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth Internode! and tree vigor! • Stem area between Node nodes! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees 2! 1/12/15! One year old Stem & Buds! Two years old Dormant Buds! Three years old Internode Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth and tree vigor! Node Latent bud - inactive lateral buds at nodes! Latent! Adventitious" Adventitious bud! - found in unexpected areas (roots, stems)! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees One year old Epicormic Growth! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Growth from dormant buds, either latent or adventitious. Internode These branches are weakly attached.! Axillary (lateral) bud - found along branches below tips! Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth and tree vigor! Node -

Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic

The Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic Stefan Sobkowiak answers questions from people like you Compiled by Hugo Deslippe Formatted by James Samuel 1 Table Of Contents Introduction 3 Tree Care 4 Types Of Trees 13 Other Plants 22 Ground Cover 24 The Soil 26 Pests and other critters 30 Animals and friendly insects 32 Orchard Patterning 34 Permaculture concepts 35 Starting an orchard 37 Business questions 45 About Stefan and the Farm 51 Profiles 59 2 Introduction In June 2014, Stefan Sobkowiak and Olivier Asselin released an incredible movie called The Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic. Subsequently, Stefan was asked many questions about permaculture, orchards, fruit trees, etc. I decided to compile the questions about the permaculture orchard and the answers here. Most of the questions are taken from the following sources: The permies.com forum, in the growies / forest garden section. Les Fermes Miracle Farms Facebook page The Permaculture Orchard: Beyond Organic’s forum section Lastly, I want to specify that I claim no authorship or any credits at all for what follows, it’s all from elsewhere and only 2 or 3 of the questions are actually mine. If you have any questions for Stefan, especially after watching the movie: The Permaculture Orchard, Beyond Organic, please post them on the movie’s website forum. This is a long thread so to find what you are looking for, you might want to do CTRL F and type the term you want in the search box. It should work in your PDF reader too. Stefan answers multiples questions everyday so not all his answers are included. -

Horticulture/Arboriculture/Landscape/Organic Farming (HOR) 1

Horticulture/Arboriculture/Landscape/Organic Farming (HOR) 1 HOR-124 Food Harvest HORTICULTURE/ 3 credits, Fall This course provides a basic knowledge of aspects of harvesting, ARBORICULTURE/ handling, storing and marketing of produce from small-scale, organic operations. Topics include: food safety laws and practices, harvest LANDSCAPE/ORGANIC and storage requirements for a variety of crops, factors that impact quality and storage ability, and post-harvest biology. Class includes a lab FARMING (HOR) component. HOR-126 Landscape Water Features Many horticulture classes will transfer as Lower Division Collegiate (LDC) 1 credits, Not Offered Every Year credits to Oregon State University. For additional information contact Methods used in building water features with emphasis placed on design, April Chastain, Horticulture Department Advisor, 503-594-3055. material selection, construction and maintenance considerations. HOR-111 Horticulture Practicum/Fall HOR-127 Landscape Lighting 2 credits, Fall 1 credits, Not Offered Every Year Practical experience with seasonal horticulture activities in the areas of Methods used with lighting in the residential landscape, with emphasis container nurseries, greenhouses, landscape management, arboriculture, placed on design, material selection, installation and maintenance and organic food production. considerations. HOR-112 Horticulture Career Exploration HOR-128 Landscape Stones & Pavers 2 credits, Spring 1 credits, Not Offered Every Year This course is a survey of the various career options available to students Methods used in building walls, patios and walkways out of stones in the horticulture industry, with emphasis on nursery and greenhouse and pavers, with an emphasis placed on design, material selection, production, retail nursery, organic fruit and vegetable production, construction and maintenance considerations.