Mall För Sammanläggningsavhandlingar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listeriose Und Toxoplasmose Sicher Essen in Der Schwangerschaft

Listeriose und Toxoplasmose Sicher essen in der Schwangerschaft Lebensmittelinfektionen durch Listerien und Toxoplasmoseerreger sind Backen und bei der industriellen Erhitzung werden die Erreger zerstört, für die meisten Menschen harmlos. In der Schwangerschaft sind sie wenn das Lebensmittel auch im Inneren mindestens zwei Minuten über selten. Sie können aber dem ungeborenen Kind schaden. Deshalb gibt es 70 Grad heiß war. Listerien können sich auch in gekühlten Lebensmitteln für Schwangere einige besondere Empfehlungen. Die wichtigste lautet: vermehren. Daher am besten nur kleine Mengen kaufen und die Produkte Essen Sie keine rohen Lebensmittel vom Tier, vor allem keine Produkte rasch verbrauchen. aus Rohmilch, kein rohes Fleisch oder rohen Fisch! Beim Kochen, Braten, Hier können Sie zugreifen: Diese Lebensmittel besser nicht essen oder vor dem Tipps für Auswahl, Einkauf, Lagerung und Zubereitung Essen ausreichend erhitzen. Hier kommen manchmal Listerien oder Toxoplasmoseerreger vor. Milch, Milchprodukte und Käse Milch und Milchprodukte aus pasteurisierter oder • Rohmilch und alles was daraus hergestellt wärmebehandelter Milch sind die richtige Wahl. wurde. Sie erkennen die Produkte an dem m o c Verbrauchen Sie die Produkte nach dem Öffnen Hinweis „Rohmilch“ oder „Vorzugsmilch“. a li o in 2--3 Tagen. Nur lange gereifter Hartkäse aus Rohmilch t o F / t ist unproblematisch. u c Essen Sie harte und feste Käsesorten und : o t o F schneiden Sie die Rinde vor dem Essen sorgfältig • halbfester Käse mit Blauschimmel, F o to : Pe ab. Kaufen Sie Käse am besten am Stück. Wenn es z. B. Gorgonzola te r M ey Käseaufschnitt sein soll, dann lassen Sie sich kleine er, aid • Käsesorten mit klebriger rot-gelber Rinde Mengen frisch aufschneiden. -

Chapter 18 : Sausage the Casing

CHAPTER 18 : SAUSAGE Sausage is any meat that has been comminuted and seasoned. Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means. A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ In simplest terms, sausage is ground meat that has been salted for preservation and seasoned to taste. Sausage is one of the oldest forms of charcuterie, and is made almost all over the world in some form or the other. Many sausage recipes and concepts have brought fame to cities and their people. Frankfurters from Frankfurt in Germany, Weiner from Vienna in Austria and Bologna from the town of Bologna in Italy. are all very famous. There are over 1200 varieties world wide Sausage consists of two parts: - the casing - the filling THE CASING Casings are of vital importance in sausage making. Their primary function is that of a holder for the meat mixture. They also have a major effect on the mouth feel (if edible) and appearance. The variety of casings available is broad. These include: natural, collagen, fibrous cellulose and protein lined fibrous cellulose. Some casings are edible and are meant to be eaten with the sausage. Other casings are non edible and are peeled away before eating. 1 NATURAL CASINGS: These are made from the intestines of animals such as hogs, pigs, wild boar, cattle and sheep. The intestine is a very long organ and is ideal for a casing of the sausage. -

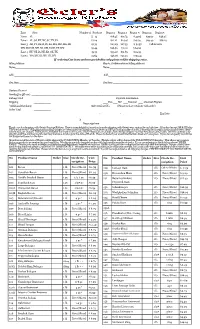

Zone State Number of Products Region 1

Zone State Number of Products Region 1 Region 2 Region 3 Region 4 Region 5 Zone 1 FL 5—14 $18.45 $19.74 $ 33.05 $39.99 $46.25 Zone 2 AL, GA, KY, NC, SC, TN, VA 15-24 $21.15 $23.45 $ 41.39 $49.99 $56.23 Zone 3 AR, CT, DE, Il, IN, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI 25-34 $24.29 $27.55 $ 54.95 Call for rates MN, MO MS, NH, NJ, OH, PA RI, VT, WV 35-44 $26.95 $31.25 $ 64.85 Zone 4 NY, WI, IA, NE, KS, OK, TX 45-54 $45.20 $51.85 $ 99.55 Zone 5 WA, MT, ID, NV, UT, WY 55-64 $46.70 $55.95 $109.45 If ordering Can items and non-perishables only please call for shipping rates . Billing Address Ship to: (If different from billing address) Name________________________________________________ Name _______________________________________________ Add. _________________________________________________ Add.________________________________________________ City, State _____________________________________________ City State _____________________________________________ Daytime Phone # _______________________________ Greeting for gift card : __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Package Total ___________ Payment Information Shipping ___________ ___ Visa ___ MC ___Discover ___ American Express *Additional Surcharge ___________ Gift Certificate No. ____ ( Please enclose certificate with order) Order Total ___________ ___ ___ ___ ___-___ ___ ___ ___-___ ___ ___ ___-___ ____ ___ Exp Date __________ X____________________________________________________ Please sign here Thank you for shopping with Geier’s Sausage Kitchen. Here is some helpful information to make shipping with Geier’s easy, enjoyable and risk free. All orders (except AK & HI) ship UPS 1-3 day service. Shipping and handling charges are determined by (A) region—your State and (B ) product quantity of order. -

WIBERG Corporation PRODUCT LIST Effective: January 1, 2011 BLENDED PRODUCTS - SAUSAGES SMOKED AND/OR COOKED

WIBERG Corporation PRODUCT LIST Effective: January 1, 2011 BLENDED PRODUCTS - SAUSAGES SMOKED AND/OR COOKED DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION ALPENWURST FRANKFURTER - SPECIAL ANDOUILLE FRANKFURTER - SUPER AUFSCHNITT GARLIC BACON GARLIC & CHEESE BACON CHEDDAR GELBWURST BANGER GOETTINGER BARESSE GRISSWUERTEL BEER HAM BIERSCHINKEN HAM - BEER BIERWURST HAM - NIAGARA BLOOD HAUSMACHER LEBERWURST BOCKWURST HEADCHEESE BOEREWORS HOT DOG BOLOGNA HUNGARIAN BRATWURST HUNTER BRATWURST - BAUERN (FARMER) ITALIAN BRATWURST - BEER JAGDWURST BRATWURST - COARSE KABANOSSY BRATWURST - FINE KALBLEBERWURST BRATWURST - GERMAN KANTWURST BRATWURST - NUERNBERG KNACKER BRATWURST - OCTOBER STYLE KNACKER - EXTRA FINE BRATWURST - ROAST KNACKWURST BRATWURST - ROAST - FLAX SEED KOLBASSA BRATWURST - ROAST GARLIC KOLBASSA - HAM BRATWURST - THUERINGER KOREAN BBQ BRAUNSCHWEIGER KRAKAUER BREAKFAST LANDJAGER BREAKFAST - REDUCED SODIUM LINGUICA CAPICOLLA LUNCHEON MEAT CEVAPCICI LYONER CHABAY MEATLOAF CHORIZO MEATLOAF - BAVARIAN CHORIZO & LONGANIZA MENNONITE COCKTAIL SAUSAGES MERGUEZ DEBRECZINER METTWURST DEBRECZINER - CHABAY METTWURST - ONION DOMACA METTWURST - WESTFALIAN DUTCH ROOKWURST MEUNCHNER WIESSWURST EL PASTOR MORTADELLA EXTRAWURST KOENGLICH OCTOBERFEST FARMER PEPPERWURST FLEISCHWURST POLISH We can make a seasoning, or we can add binder and/or cure to make a complete easy to use unit! WIBERG Corporation PRODUCT LIST Effective: January 1, 2011 BLENDED PRODUCTS - SAUSAGES SMOKED AND/OR COOKED DESCRIPTION DESCRIPTION PORCHETTA PRESSWURST RUEGENWALDER TEEWURST SAHNELEBERWURST SCHINKENSPECK SCHINKENWURST SCHLACKWURST SEJ - WITH ONION SMOKIE - BAVARIAN SREMSKA - HOT SREMSKA - SWEET SUJUK - HOT SUJUK - MILD SUJUK - TURKISH SULMTALER KRAINER SUMMER THURINGER ROTTWURST TONGUE TYROLER WEINER WEINER - CONEY ISLAND WEINER - REDUCED SODIUM WEINER - TOFU WIESSWURST WIESSWURST - MUENCHNER ZWIEBELMETTWURST We can make a seasoning, or we can add binder and/or cure to make a complete easy to use unit! . -

Imported Food Risk Statement Uncooked Ready-To-Eat Spreadable Sausages and Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli

Imported food risk statement Uncooked ready-to-eat spreadable sausages and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli Commodity: Uncooked spreadable sausages that are ready-to-eat (RTE). An example of this type of product includes some varieties of teewurst. Ambient stable sealed packages are not covered by this risk statement. Microorganism: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) Recommendation and rationale Is STEC in uncooked RTE spreadable sausages a medium or high risk to public health: Yes No Uncertain, further scientific assessment required Rationale: • Consumption of uncooked RTE spreadable sausages has been epidemiologically associated with human illness due to STEC and infections can have severe consequences • Ruminants are the main animal reservoir for STEC, however, STEC can also be found in other animals and birds • International surveillance data have shown detections of STEC in uncooked RTE spreadable sausages General description Nature of the microorganism: E. coli are facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria. They are found in warm-blooded animals and humans as part of the normal intestinal flora (FSANZ 2013). The majority of E. coli are harmless, however some have acquired specific virulence attributes, such as Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), which can cause severe diarrheal disease in humans (FDA 2012). Major foodborne pathogenic STEC strains include O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, O157 (FDA 2012) and O104 (ECDC/EFSA 2011). The major animal reservoir of STEC is ruminants. STEC can also colonise other animals and birds, although the incidence of STEC is lower than in ruminants (FSANZ 2013; Meng et al. 2013). Growth of E. coli can occur at temperatures between 7 – 46°C, pH of 4.4 – 10.0 and a minimum water activity of 0.95 when other conditions are near optimum. -

Raw Sausage & Raw Cured Meat Products

RAW SAUSAGE & RAW CURED MEAT PRODUCTS PRODUCT CATALOGUE RAW SAUSAGE & CONTENTS RAW CURED MEAT PRODUCTS Naturally ripened raw sausages and raw cured meat products that are fermented over long periods of time are among the most sophisticated meat products around. Statistics published by the German RAW SAUSAGE 04 Butchers’ Association show that the average German eats five kilograms of raw sausage a year – and prefers salami, mettwurst and teewurst. Seasoning 05 Firm or spreadable, cold-smoked or air-dried, with or without edible mould – RAPS develops all Raw sausage – firm 06 solutions needed for every end product. Originally created because of their long shelf-life, these Raw sausage – spreadable 08 products are today enjoyed primarily for their fine flavour and aroma. Production methods have been Raw sausage – thin-calibre 10 refined over time, but raw sausage production remains the ultimate discipline of the butcher’s trade. Raw sausage production technology 12 What matters is the balance between raw materials, additives and the maturing process – we at RAPS take care of the rest. Starter cultures 14 TRADITION AND TECHNOLOGY FOR THE ULTIMATE QUALITY Technical aids 17 Modern raw sausage and raw cured meat production is based on traditional craftsmanship and Sausage casings 18 sophisticated technology. Our years of expertise in raw sausage production has enabled us to develop a wide range of products for making raw sausages. We constantly evolve and are always developing new raw sausage innovations. From specially designed starter cultures which we RAW CURED MEAT PRODUCTS 20 purchase from our own technology development centre in Austria, to exceptional seasoning blends, to high-quality sausage casings that give the product its final shape – this comprehensive product Seasoning 21 catalogue focusing on raw sausage and raw cured meat products contains everything you need to make manufacturing these meat products easy and safe, helping you to create flagship products Starter cultures 21 that look, taste and smell superb. -

Raps Van Hees Gewürzmüller Product List

PRODUCT LIST RAPS▪ VAN HEES ▪ GEWÜRZMÜLLER March 2020 CBS Foodtech Pty Ltd 2/7 Jubilee Avenue Warriewood NSW 2102 . P - 02 9979 6722 F - 02 9979 6511 E - [email protected] W - www.cbsfoodtech.com.au RAPS SEASONINGS & ADDITIVES Simmer Sausage Type Products Code Description Function UOM R39610 Alpini 1kg Pure line no MSG kg R0130 Cabanossi 1kg Kabanos kg R1859 Cooked Pepperoni 1kg kg R0254 Debreziner 1kg kg R39366 Meat Loaf 1kg Pure line no MSG kg R39364 Senator Gold 1kg Pure line no MSG kg R0277 Vienna Gold 1kg Wiener, Frankfurter kg R0287 Vienna Red 1kg Wiener, Frankfurter kg Fresh Sausage Type Products Code Description Function UOM R0541 Bavarian Weisswurst 1kg Weisswurst sausage kg R0547 Cevapcici 1kg kg R39722 Chorizo 1kg no MSG kg R0520 Fresh Bratwurst 1kg fresh & frying sausage kg R0533 Merguez Bratwurst 1kg French style sausage kg R0554 Minced Meat Mix 1kg Mix for Rissoles & Crumb production kg R0530 Nürnberger Bratwurst 1kg fresh & simmer sausage kg R0532 Thüringer Bratwurst 1kg fresh & frying sausage kg Cooked Sausage Type Products Code Description Function UOM R39609 Bloodwurst 1kg Black Pudding no MSG kg R0325 Cristallfix 1.5kg Seasoned Gelatine kg R93875 Cristal Spice 1kg Pureline - Brawn, Presswurst seasoning no MSG kg R94811 Leberwurst NG 1kg Pureline no MSG kg Fermented Sausage Type Products Code Description Function UOM R0010387 Biostart Sprint 25g Starter Culture each R00174 Onion Mettwurst-Soft 1kg Spreadable Onion Mettwurst kg R0170 Pfefferjager 1kg Dry Salami, Green Pepper taste kg R0117 Salami Quick 1kg Dry Salami -

Development of Beef Sausages Through Bovine Blood Utilization As Fat Replacer to Reduce Slaughterhouse By-Product Losses

DEVELOPMENT OF BEEF SAUSAGES THROUGH BOVINE BLOOD UTILIZATION AS FAT REPLACER TO REDUCE SLAUGHTERHOUSE BY-PRODUCT LOSSES By Pius Mathi (B.Sc. FST, University of Nairobi) A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI. DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE, NUTRITION AND TECHNOLOGY November, 2016. Declaration This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. Signed: ___________________________ Date: ______________________________ Pius Mathi A56/71580/2014 Department of Food Science, Nutrition and Technology This thesis has been submitted with our approval as university supervisors. Signed: ___________________________ Date: ____________________________________ Dr. Catherine N. Kunyanga (PhD) Department of Food Science, Nutrition and Technology Signed: __________________________ Date: _____________________________________ Prof. Jasper K. Imungi (PhD) Department of Food Science, Nutrition and Technology ii UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI PLAGIARISM DECLARATION FORM NAME OF STUDENT : PIUS MATHI REGISTRATION NUMBER: A56/71580/2014 COLLEGE: COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND VETERINARY SCIENCES FACULTY/SCHOOL/INSTITUTE: AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT: FOOD SCIENCE NUTRITION AND TECHNOLOGY COURSE NAME: M.Sc. FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY TITLE OF THE WORK: DEVELOPMENT OF BEEF SAUSAGES THROUGH BOVINE BLOOD UTILIZATION AS FAT REPLACER TO REDUCE SLAUGHTERHOUSE BY- PRODUCT LOSSES DECLARATION 1. I understand what Plagiarism is and I am aware of the University’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been submitted elsewhere for examination, award of a degree or publication. Where other people’s work or my own work has been used, this has properly been acknowledged and referenced in accordance with the University of Nairobi’s requirements. -

The European Sausage Industry

THE EUROPEAN SAUSAGE INDUSTRY by John Schut* I. HISTORY another, e.g. cookc d sausage, became more and more known and popular in the northern and eastern Regular meat supply to man began with the domes- countries. But it was not until the beginning of the tication of the mammalian species sheep, cattle and 20th century that - due to the development of cli- pigs. The sheep was domesticated with the aid of mate chambers - acceptable raw and dry sausage dogs before a settled agriculture was established could be produced all over Europe and the whole (7000 B.C. ). By 3500-3000 B.C. several breeds of year around. domestic sheep were known in Mesopotamia and Egypt. The domestication of cattle followed the estab- A second period of spreading happened after lishment of settled agriculture about 5000-4000 B.C. World War I1 when, as a consequence of extensive Evidence is found that about 3000 B.C. cows were business, but, above all, holiday traveling, the pro- milked, and cattle fattened by forced feeding in Egypt duction of cooked sausage got under way in the south at that time. It is assumed that the domestication of European countries. pigs is from a later date. However, in an area of However, the mechanism behind the distribution Europe, now known as Hungary, pigs were domesti- was a different one. In north and middle Europe raw cated by about 2500 B.C. In the Greco-Roman period and dry sausage production grew rapidly because the the animal became of great importance, when hams people liked them. -

German Sausages

German Sausages Blood Sausage - Blutwurst Blutwurst, or blood sausage, is made with congealed pig or cow blood and also contains fillers like meat, fat, bread or oatmeal. It is sliced and eaten cold, on bread. Bockwurst Traditionally consumed with — you guessed it — bock beer, bockwurst is made with a mixture of ground veal and pork, with the addition of cream and eggs. It's flavored with grassy, mild parsley as opposed to the stronger herbal flavors of marjoram and thyme that season other kinds of sausage. Serve it with sharp, piquant yellow mustard to bring out its subtle flavor. Bratwurst Bratwurst and Rostbratwurst is a sausage made from finely minced pork and beef and usually grilled and served with sweet German mustard and a piece of bread or hard roll. It can be sliced and made into Currywurst by slathering it in a catchup-curry sauce. Bregenwurst Bregenwurst comes from Lower Saxony and is made of pork, pork belly, and pig or cattle brain. It is often stewed and served with kale. It is about the size and color of Knackwurst. Nowadays, Bregenwurst does not contain brain as an ingredient. Currywurst Currywurst is a fast food dish of German origin consisting of steamed, then fried pork sausage whole or less often cut into slices and seasoned with curry ketchup, regularly consisting of ketchup or tomato paste topped with curry powder, or a ready-made ketchup seasoned with curry and other spices. The dish is often served with French fries. Frankfurter It Also known as wienerwurst, a long, thin sausage that is flavorful pork and beef finely chopped with salt and spices. -

S You Favorite Cold Cuts Sandwich?

What’s You Favorite Cold Cuts Sandwich? A cold cut are those yummy, chilled slices of meat you get at the deli. You might pop them in sandwiches, you might have them drizzled with oil and with a few slices of cheese – whatever way you like them, Cold Cuts Day is all about celebrating all the tasty meats that are somehow even tastier when served up in slices. You might know cold cuts as luncheon meat, sliced meats, smallgoods, Colton or simply cold meats. You can usually buy them packaged up and ready to eat at the grocery store or at your local deli, and depending on where you go you might be able to get them sliced to order. Because meat like this is pre-coooked, usually into sausage shapes or loaves, once it’s sliced its ready to eat right away. Perfect for getting your savoury fix in a hurry! The History of Cold Cuts Day Dagwood Bumstead holding a Dagwood sandwich in a handscrew clamp Luncheon meats have been around for generations. Their simple preparation and ease of use has led to them being a favorite sandwich filling, and these days its not uncommon to find them served alone or with bread in swanky restaurants and bars. Cold cuts can be simply slices of meat straight from a cooked joint, which is then packaged and served up. These are known as whole cuts, where the meat is solid muscle and no other meats were added to the product. However, other cold cuts like salamis and sausages are processed with other meat proteins to make a super tasty, usually quite tidy-looking block of meat. -

12019 Viscofan Plastic Casing

PLASTIC CASINGS AND PACKAGING SOLUTIONS The plastic range from Viscofan is unbeatable in variety. Whether you are looking for “shrink bags“, casings which are “permeable“ to smoke or “barrier“ casings, in straight or a round version, Viscofan offers the right casings for your applications. These environmentally-friendly products guarantee easy handling and an immaculate finished product. Our wide range of colours and convertings cover every customer demand. Black Pudding Bologna Beef Jelly Meat Deli Hams Ham Sausage Liver Sausage Lyoner Pork Loaf Hot Dog Knackwurst Teewurst Wiener Bockwurst Frankfurter Suçuk Smoked hams Melted cheese Sauces Soups Skin-on frankfurters Chorizo Cheese sausages Mini sausages Boneless deli meats Chilled meat Relleno Mortadella Tuna Ham Chopped Pork Viscofan plastic casings are available in many converting presentations to suit any production process efficiently. Whether in ready to use or long shirring lengths materials our variety of tailor-made presentations make your production easier and more efficient. The casing company VISCOFAN PLASTIC CASINGS Tailor casing solutions designed to bring cost-efficiency, safety and better quality to the food industry. ü Superior barrier properties to maximize product shelf-life and cooking yields. ü Tailored mechanical properties eliminating breakage in the plant and through distribution. ü Purpose-designed stretch ratio to get uniform sizing and appealing final products. ü Excellent meat adhesion with no purge and options to modulate peeling processes. ü Smoke-permeable versions giving smoke colour, flavour and aroma to the products. ü Large variety of casing colours and high quality printing technology for brand differentiation. ü Ready to use sticks, resulting in improved hygiene and increased efficiency.