Public-Private Sector Partnerships Mutual Benefits for Business and Protected Areas Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential European Bison (Bison Bonasus) Habitat in Germany

PROJECT REPORT Potential European bison (Bison bonasus) habitat in Germany Tobias Kuemmerle Humboldt-University Berlin Benjamin Bleyhl Humboldt-University Berlin Wanda Olech University of Warsaw & European Bison Friends Society Kajetan Perzanowski Carpathian Wildlife Research Station MIZ, PAS & European Bison Friends Society 1 PROJECT REPORT CONTENTS CONTENTS ...............................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................3 HISTORIC DISTRIBUTION OF EUROPEAN BISON IN EUROPE .....................................................................................4 EUROPEAN BISON HABITAT PREFERENCES ..............................................................................................................6 HABITAT USE OF CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN BISON POPULATIONS .......................................................................................... 6 PALEO-ECOLOGICAL DATA ON EUROPEAN BISON HABITAT USE ............................................................................................... 10 MAPPING EUROPEAN BISON HABITAT IN GERMANY ............................................................................................ 10 APPROACH ................................................................................................................................................................. -

11701-19-A0558 RVH Landmarke 4 Engl

Landmark 4 Brocken ® On the 17th of November, 2015, during the 38th UNESCO General Assembly, the 195 member states of the United Nations resolved to introduce a new title. As a result, Geoparks can be distinguished as UNESCO Global Geoparks. As early as 2004, 25 European and Chinese Geoparks had founded the Global Geoparks Network (GGN). In autumn of that year Geopark Harz · Braunschweiger Land · Ostfalen became part of the network. In addition, there are various regional networks, among them the European Geoparks Network (EGN). These coordinate international cooperation. 22 Königslutter 28 ® 1 cm = 26 km 20 Oschersleben 27 18 14 Goslar Halberstadt 3 2 1 8 Quedlinburg 4 OsterodeOsterodee a.H.a.Ha H.. 9 11 5 13 15 161 6 10 17 19 7 Sangerhausen Nordhausen 12 21 In the above overview map you can see the locations of all UNESCO Global Geoparks in Europe, including UNESCO Global Geopark Harz · Braunschweiger Land · Ostfalen and the borders of its parts. UNESCO-Geoparks are clearly defi ned, unique areas, in which geosites and landscapes of international geological importance are found. The purpose of every UNESCO-Geopark is to protect the geological heritage and to promote environmental education and sustainable regional development. Actions which can infl ict considerable damage on geosites are forbidden by law. A Highlight of a Harz Visit 1 The Brocken A walk up the Brocken can begin at many of the Landmark’s Geopoints, or one can take the Brockenbahn from Wernigerode or Drei Annen-Hohne via Schierke up to the highest mountain of the Geopark (1,141 meters a.s.l.). -

Case Study Eifel Initiative Final

Eifel Initiative for the Future, Germany Urban-rural linkages enhancing European territorial competitiveness - Mini case study on business clusters Short description of the setting The Eifel region is a low mountain range in western Germany, bounded on the north, east, and south by the rivers and vineyards of the Ahr, Rhine, and Moselle, and by the forest of the Ardennes of Belgium and Luxembourg in the west. It covers an area of nearly 700.000 ha total, comprising 10 districts in two German Federal States (three districts in North Rhine-Westphalia and seven in Rhineland-Palatinate). All in all, the Eifel region gives home to about 900.000 inhabitants in 53 cities and towns. Amidst the cities of Aachen, Koblenz and Trier which mark the borders of Eifel, the region is rather lacking in infrastructure, with few industrial clusters, but mining, agriculture, viniculture, forestry and dairy farming predominating, and tourism as a growing sector. Savage beauty was and is one of the features of Eifel, and since 2004 about 110 km² of the Eifel have been protected as the nature reserve “Eifel National Park”. Vis à vis these conditions, the need for a joint strategy and co-operation for the development of Eifel as a competitive region was recognised by many actors across borders, and first implemented for the field of tourism. Innovative activity "Eifel - We are future" – with this motto, 10 Eifel districts, 53 local governments und 8 regional chambers of commerce in the two neighbouring German Federal States of Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia and the German-speaking Community of Belgium have affiliated in the association “Eifel Initiative” in 2005, and thus established a remarkable regional partnership for creation of value. -

NATURE EXPERIENCE and EDUCATION for People with Disabilities Part 1

nature without barriers NATURE EXPERIENCE AND EDUCATION for people with disabilities Part 1 Guided nature experiences and educational programmes nature without barriers Picture title page: The Eifel National Park has been a reference for inclusive nature experiences in Germany for years. Here: An excursion in the barrier-free nature experience area „Wilder Kermeter“. 2 nature without barriers CONTENT 1. Introduction 5 1.1 About the project 5 1.2 Project partners 6 1.3 Work with this brochure 7 2. Principles of accessibility 11 2.1 Legal issues 11 2.2 Accessibility 12 2.3 Barrier-free communication 13 2.4 Respectful interaction 15 3. Impaired people 19 3.1 People with motor impairments 19 3.2 Visually impaired and blind people 21 3.3 Deaf and hard of hearing people 23 3.4 People with learning difficulties 25 4. Planning and preparation 27 4.1 Accessibility check 27 4.2 Infrastructure 28 4.2.1 Accessibility of nature conservation centres/areas 28 4.2.2 Buildings 29 4.2.3 Toilets 30 4.2.4 Trails, terrain and vantage points 31 4.3 Special services and support on site 32 4.3.1 People with motor impairments 32 4.3.2 Visually impaired and blind people 33 4.3.3 Deaf and hard of hearing people 34 4.3.4 People with learning difficulties 35 4.4 Best practice examples 29 4.4.1 Eifel National Park (Germany) 39 4.4.2 Barefoot-park Beelitz-Heilstätten (Germany) 40 4.4.3 Naturpark Kaunergrat (Austria) 41 4.4.4 Herb Valley, Zánka (Hungary) 42 5. -

Aeb E Sep 2020 NAEI62 Aeb06 Offen.Qxd 15.05.2020 14:38 Seite 2 Seite 14:38 15.05.2020 2020 NAEI62 Aeb06 Offen.Qxd Aeb E Sep

5 4 3 2 more information, please see table). table). see please information, more forests for rearing its young. In total, approximately 1,000 wildcats live live wildcats 1,000 approximately total, In young. its rearing for forests ride through expansive landscapes in a horse-drawn carriage (for (for carriage horse-drawn a in landscapes expansive through ride wise benefits from the National Park. It makes use of the continuous continuous the of use makes It Park. National the from benefits wise www.nationalpark-eifel.de www.nationalpark-eifel.de born Plateau, from April to the end of October it is also possible to to possible also is it October of end the to April from Plateau, born The rare wildcat, almost exterminated during the 19th century, like- century, 19th the during exterminated almost wildcat, rare The For additional information, please see the website: website: the see please information, additional For ger tour to the deserted village of Wollseifen and back. On the Drei- the On back. and Wollseifen of village deserted the to tour ger diversity and exceptional scenery. scenery. exceptional and diversity and the Urftsee reservoir. In addition, every Sunday there is a free ran- free a is there Sunday every addition, In reservoir. Urftsee the and flowers protected by the Park. Park. the by protected flowers develop in the Eifel National Park, which is already fascinating in its its in fascinating already is which Park, National Eifel the in develop Your Eifel National Park Administration Administration Park National Eifel Your where you can enjoy a unique view of the National Park landscape landscape Park National the of view unique a enjoy can you where St Bernhard’s lily, bog bean and perennial honesty are other valuable valuable other are honesty perennial and bean bog lily, Bernhard’s St natural dominance. -

Germany Facts

Germany Facts The word for Germany in the German language is Deutschland. GTheE populatRion of GerMmany was aroAund 82 mNillion in 20Y10. The capital of Germany is Berlin; it is also the largest city. Other major cities include Munich, Hamburg, Cologne, Stuttgart and Frankfurt. Germany is a member of the European Union. Germany has had an unsettled history, including the Nazi regime and tension between East and West Germany (which were reunified in 1990). Countries that border Germany include Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Luxembourg, Poland and Switzerland. Germany has the largest economy in Europe. Large German companies include BMW, Adidas, SAP, Mercedes- Benz, Nivea, Audi, Bayer, Volkswagen and Siemens. https://www.sciencekids.co.nz/sciencefacts/countries/germany.html Germany Facts Germany has a number of important natural resources, including copper, nickel, natural gas, uranium and coal. GGEermanyR is in the pMrocess of phAasing outN nuclear Ypower plants. There are many national parks in Germany, which include the Bavarian Forest National Park, Jasmund National Park, Harz National Park, and the Wadden Sea National Parks. Over 100 Germans have been awarded the Nobel prize in their field, including Albert Einstein, who was born in Germany. Germany has been home to famous composers such as Johann Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven and Richard Wagner. The German Coat of Arms features a black eagle against a yellow shield. Football (soccer) is the most popular sport in Germany. https://www.sciencekids.co.nz/sciencefacts/countries/germany.html. -

HARZ MOUNTAINS 229 Quedlinburg Thale Gernrode © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely © Wernigerode Harz National Park Brocken Goslar (Harz Journey; 1824)

© Lonely Planet Publications 229 Harz Mountains The Harz Mountains rise picturesquely from the North German Plain, covering an area 100km long and 30km wide at the junction of Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. Although the scenery here is a far cry from the dramatic peaks and valleys of the Alps, the Harz region is a great year-round sports getaway, with plenty of opportunities for hiking, cycling and skiing (downhill and nordic) in and around the pretty Harz National Park. The regular influx of visitors in all seasons is testament to the enduring appeal of the Harz; historically, too, its status as a prime national holiday destination has never been questioned. From 1952 until reunification, the region was divided between West and East Germany, effectively becoming an uneasy political holiday camp straddling the Iron Curtain. The Brocken (1142m) is the focal point, and has had more than its fair share of illustri- ous visitors: the great Goethe was frequently seen striding the local trails and set ‘Walpur- gisnacht’, an early chapter of Faust, on the mountain, while satirical poet Heinrich Heine spent a well-oiled night here, as described in Harzreise (Harz Journey; 1824). Elsewhere the charming medieval towns of Wernigerode and Quedlinburg pull the crowds, while equally venerable steam trains pull them along between the mountain villages, spas and sports resorts that litter the region. Get out your knee socks or your ski mask and treat yourself to a taste of the active life. HIGHLIGHTS Pagan Rituals Trek to the Brocken or -

Explore Germany with Fun Facts

In this Bag: 1 sheet brown construction paper 1 piece of red cording Recipe for Traditional Ginger Bread Heart Cookies (Lebkuchenherzen) What you Need at Home: Scissors Hole puncher Markers, colored pencils or crayons Learn about Germany and craft with us by following the instructional video on our virtual hub: http://www.creativeartsguild.org/events/annual- events/festival1/childrens-hill Fun Facts about Germany: The name for Germany in the German language is Deutschland. The population of Germany was around 82 million in 2010. The capital of Germany is Berlin, it is also the largest city. Other major cities include Munich, Hamburg, Cologne, Stuttgart and Frankfurt. Germany is a member of the European Union. Germany has had an unsettled history, including the Nazi regime and tension between East and West Germany (which were reunified in 1990). Countries that border Germany include Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, the Czech Republic, France, Luxembourg, Poland and Switzerland. Germany has the largest economy in Europe. Large German companies include BMW, Adidas, SAP, Mercedes-Benz, Nivea, Audi, Bayer, Volkswagen and Siemens. Germany has a number of important natural resources, including copper, nickel, natural gas, uranium and coal. Germany is in the process of phasing out nuclear power plants. There are many national parks in Germany include the Bavarian Forest National Park, Jasmund National Park, Harz National Park, and the Wadden Sea National Parks among others. Over 100 Germans have been awarded the Nobel prize in their field, including Albert Einstein, who was born in Germany. Germany has been home to famous composers such as Johann Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven and Richard Wagner. -

Causes and Potential Solutions for Conflicts Between Protected Area Management and Local People in Germany

Causes and Potential Solutions for Conflicts between Protected Area Management and Local People in Germany Eick von Ruschkowski, Department of Environmental Planning, Leibniz University Han- nover, Herrenhäuser Strasse 2, 30419, Hannover, Germany; [email protected] hannover.de Introduction The designation of protected areas (e.g. national parks) often leads to conflicts between local communities and the area’s administration. This phenomenon exists worldwide (Pretty and Pimbert 1995) and is probably as old as the national park idea itself. These conflicts often affect both the protected areas and the local communities as strained relations bear the dan- ger of gridlock on park planning, conservation objectives or regional economic development. As national parks and surrounding communities are highly dependent on each other (Jarvis 2000), the task of managing stakeholder interests and potential use conflicts should be of high priority for park managers. National parks in Germany (as much of Central Europe’s protected areas) are often very vulnerable to such conflicts for a number of reasons. Their history is quite recent, with the oldest park having been established less than 40 years ago. On the other hand, the German landscape has been altered throughout many centuries, hence creating cultural landscapes, rather than unimpaired wilderness. Thus, the designation of national parks has caused con- flicts in the past, mainly along the lines of the continuation of traditional uses vs. future (non- )development, often additionally fuelled by management issues (local vs. state vs. federal). Additionally,a high population density puts protected areas more likely close to urban areas. Against this background, the management of stakeholder issues in order to increase support among local communities remains one of the most important sociological challenges for Ger- man park managers. -

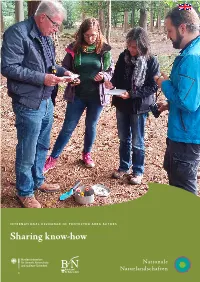

Sharing Know-How Why Is It Worth Looking at the Broader Picture?

INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE OF PROTECTED AREA ACTORS Sharing know-how Why is it worth looking at the broader picture? “Looking at the broader picture softens the boundaries in thinking, finds solutions, and clarifies alternatives, possibilities, new approaches and self-perception.„ Participant in the ANNIKA final workshop Jens Posthoff Contents Foreword 3 Project description 4 Austria Accessibility and inclusion in protected areas: Introduction to the study visit 5 Around the world in 7 days by wheelchair? or: 6 days barrier-free through Austria? 6 Developing possibilities for barrier-free nature: involve people with disabilities! 8 The service chain in barrier-free tourism – practical examples from Austria 10 Information materials for accessibility – practical example of Rolli Roadbook 12 Comparison of aids for people with reduced mobility in protected areas 14 Experience wilderness up close – opportunities for people with visual impairments 16 United Regional development and tourism in protected areas: Introduction to the study visit 18 Kingdom Regional development through trekking opportunities in national parks 19 Recreation and health in protected areas 21 Regional development, tourism and nature conservation: financing options from third-party funds 23 Anchoring protected areas in society and instruments to further strengthen them. 25 Or: how to live more successfully with numerous allies. Cooperation programmes of protected areas and businesses 27 Volunteering and management 29 Germany Regional development and tourism in protected areas: -

Introduction Day To

2-Country 7-River route - 9 dagen DUTCH BIKETOURS - EMAIL: [email protected] - TELEPHONE +31 (0)24 3244712 - WWW.DUTCH-BIKETOURS.COM 2-Country 7-River route 9 days, € 650 Introduction The water in the rivers slowly flows past…. An (international) bike ride along rivers, from wide to narrow, rippling through a wide variety of beautiful landscapes, including the Eifel National Park. This gives you as a cyclist a wonderful feeling of peace. The busy shipping traffic on the Maas and Rhine adds an extra dimension to this. Day to Day Day 1 Arrival in Venlo Travel on your own to Bilderberg Hotel De Bovenste Molen **** in Venlo; at the beautifully situated hotel on the edge of Venlo, there is ample free parking. Day 2 Venlo – Herten 50 km Follow the numbered cycling route through the quiet suburbs of Venlo and past the station to the Maas; From here, follow the Maas route in a southerly direction on the right bank of the Maas. At the Monastery village of Steyl, cross the Maas with the ferry and continue the Maas route via the castle village of Baarlo to the characteristic Maas village of Kessel. Here cross again the Maas with the ferry and then continue the Maas route via the Drakendorp Beesel to Roermond. From the center of Roermond it is still a few water-rich kilometers to the town of Herten. Day 3 Herten – Düren 79 km Follow the beautiful (numbered) cycling route through the valley of the Roer, via Sint Odiliënberg and Vlodrop, to the border with Germany. -

Joint Press Release of the Eifel National Park Forestry Office/Wald Und Holz (Forest and Wood) NRW and the North Eifel Nature Park

Joint press release of the Eifel National Park Forestry Office/Wald und Holz (Forest and Wood) NRW and the North Eifel Nature Park The Eifel National Park receives final recognition as an International Dark Sky Park State Minister for the Environment Heinen-Esser: the protection of the starry night sky serves the protection of health, species and climate and makes it possible to experience fascinating nature at night. Schleiden-Gemünd/Nettersheim, 5 April 2019. Experiencing the starry night sky with its sparkling celestial bodies is a special experience for a lot of people that is only possible in a few places in Germany. One of these places is the Eifel National Park. Since 2010, a regional initiative has successfully been campaigning to protect the night sky and preserve the natural night landscape. In 2014, it was awarded the provisional title of the first "International Dark Sky Park" in Germany. Now, this initiative can look forward to its final recognition as the International Dark Sky Park Eifel National Park. At the observatory of the astronomy workshop "Stars without Borders" in the Eifel National Park, Dr Andreas Hänel, the highest representative of the International Dark Sky Association (IDA) in Germany, presented the certificate of recognition to the Minister for the Environment, Ursula Heinen-Esser, and the Head of the Eifel National Park Administration, Michael Röös. Recognition as a protected area by the International Dark Sky Association (IDA) is an honour with which only a few regions worldwide can advertise; Germany has only four of them. For the Eifel National Park, which turned 15 this year, this honour is a nice "birthday present".