Article 15 Communication to the Icc Office of the Prosecutor Regarding the Targeting of the Pro-Biafran Independence Movement in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Secession of Biafra, 1967–1970

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2020-06 Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa Thomas, Charles G.; Falola, Toyin University of Calgary Press Thomas, C. G., & Falola, T. (2020). Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112216 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca SECESSION AND SEPARATIST CONFLICTS IN POSTCOLONIAL AFRICA By Charles G. Thomas and Toyin Falola ISBN 978-1-77385-127-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Civil War 1968-1970

Copyright by Roy Samuel Doron 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Roy Samuel Doron Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Forging a Nation while losing a Country: Igbo Nationalism, Ethnicity and Propaganda in the Nigerian Civil War 1968-1970 Committee: Toyin Falola, Supervisor Okpeh Okpeh Catherine Boone Juliet Walker H.W. Brands Forging a Nation while losing a Country: Igbo Nationalism, Ethnicity and Propaganda in the Nigerian Civil War 1968-1970 by Roy Samuel Doron B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2011 Forging a Nation while losing a Country: Igbo Nationalism, Ethnicity and Propaganda in the Nigerian Civil War 1968-1970 Roy Samuel Doron, PhD The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Toyin Falola This project looks at the ways the Biafran Government maintained their war machine in spite of the hopeless situation that emerged in the summer of 1968. Ojukwu’s government looked certain to topple at the beginning of the summer of 1968, yet Biafra held on and did not capitulate until nearly two years later, on 15 January 1970. The Ojukwu regime found itself in a serious predicament; how to maintain support for a war that was increasingly costly to the Igbo people, both in military terms and in the menacing face of the starvation of the civilian population. Further, the Biafran government had to not only mobilize a global public opinion campaign against the “genocidal” campaign waged against them, but also convince the world that the only option for Igbo survival was an independent Biafra. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

Geology and Economic Evaluation of Odobola, Ogodo Feldspar Mineral Deposit, Ajaokuta Local Government Area, Kogi State, Nigeria

Earth Science Research; Vol. 2, No. 1; 2013 ISSN 1927-0542 E-ISSN 1927-0550 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Geology and Economic Evaluation of Odobola, Ogodo Feldspar Mineral Deposit, Ajaokuta Local Government Area, Kogi State, Nigeria Ako Thomas Agbor1 & Onoduku Usman Shehu1 1 Department of Geology, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria Correspondence: Ako Thomas Agbor, Department of Geology, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria. Tel: 234-806-757-3526. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 27, 2012 Accepted: August 10, 2012 Online Published: September 6, 2012 doi:10.5539/esr.v2n1p52 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/esr.v2n1p52 Abstract The Odobola, Ogodo area is part of the basement complex of Nigeria and is underlain mainly by schists and intrusive granitic and pegmatitic rocks along with sediments weathered from these rocks. The granitic and pegmatitic intrusives are source of feldspar with a significant K2O component (k-feldspar). A study of the area reveals the occurrence of feldspar deposit hosted by granitic and pegmatitic intrusives. Geochemical data for the feldspar samples show average Si2O, Al2O, K2O, Na2O, CaO, Fe2O3, MgO and TiO2 contents of 65.81wt%, 16.67wt%, 10.67wt%, 5.83wt%, 0.02wt%, 0.26wt%, 0.5wt% and < 0.001wt% respectively while mineralogical results reveals average anorthite, orthoclase and albite contents of 0.42%, 85.40% and 14.06% respectively. The results of the analyses compared with those of the British international Standard (BIS) shows that the feldspar deposit can be used in industries such as glass, ceramic tiles, sanitary wares and insulators. -

Growth of the Catholic Church in the Onitsha Province Op Eastern Nigeria 1905-1983 V 14

THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OP EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 V 14 - I BY REV. FATHER VINCENT NWOSU : ! I i A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY , DEGREE (EXTERNAL), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1988 ProQuest Number: 11015885 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015885 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 s THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OF EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 By Rev. Father Vincent NWOSU ABSTRACT Recent studies in African church historiography have increasingly shown that the generally acknowledged successful planting of Christian Churches in parts of Africa, especially the East and West, from the nineteenth century was not entirely the work of foreign missionaries alone. Africans themselves participated actively in p la n tin g , sustaining and propagating the faith. These Africans can clearly be grouped into two: first, those who were ordained ministers of the church, and secondly, the lay members. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

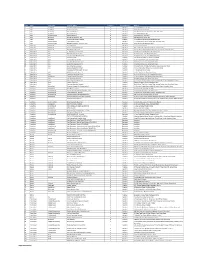

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Household Water Demand in the Peri-Urban Communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria

Vol. 6(6), pp. 237-243, August, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/JGRP2013.0385 Journal of Geography and Regional Planning ISSN 2070-1845 © 2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP Full Length Research Paper Household water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria E. E. Ezenwaji1*, P.O. Phil-Eze2, V. I. Otti3 and B. M. Eduputa4 1Department of Geography and Meteorology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. 2Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. 3Civil Engineering Department, Federal Polytechnic, Oko, Nigeria. 4Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. Accepted 22 July, 2013 The aim of this paper is to determine relevant factors contributing to the water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka capital city. Towards achieving this aim, questionnaire were developed and served on the households in various communities to collect relevant data on the 13 physical and socio- economic factors we earlier identified as influencing water demand in the area. Water quality was ascertained through microbiological analysis of water samples. The major analytical techniques used were multiple correlations, the result of which was subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Principal Component Regression. Result shows that the 13 variables combined to contribute 90.0% of water demand in the area. Furthermore, the low standard error of estimates of 0.029 litres shows that water demand in the communities could be predicted using the 13 variables. Policy and planning measures to improve the water supply situation of the area were suggested. Key words: Capital, communities, factors, peri-urban, water demand. -

Company Profile

COMPANY PROFILE Environment & Monitoring • Coastal & Port Engineering • Hydraulics 03/2018 We invite you for an inside view into our consulting company’s experience and expertise in environment & water resource management, coastal & port engineering, hydraulics & numerical modelling and environmental monitoring. We are committed to the code of best practice and environmental sustainability to provide optimal solutions for our clients. Therefore, we operate high-end equipment for measurements and compute numerical simulations on a flexible and powerful UNIX cluster for a suite of established simulation packages (2D and 3D) for coastal engineering, hydrodynamics and sediment transport. With our 15 years of experience with partners and clients in the industry and in the public sector we can offer tailor-made solutions for your problems. Just take a look at our projects! Since 2007 we are located in our new office building in Wettmar near Hannover. The 120 sqm of office, 30 sqm for presentation & training and the 120 sqm of work shop provide the ideal infrastructure for our work. For more information visit our website: www.matheja-consult.de Curriculum Vitae – Dr. Andreas Matheja: Education 1984 – 1991 Technical University of Hannover, Civil Engineering, Specialization: Water Resources Management, Coastal Engineering, Hydraulics Degree: Diploma 1991 – 1995 PHD-Thesis on "Long-term Management of Conjunctive Use Systems by Embed- ding Groundwater Quality into the Multi- objective Decision Making Process " Degree: Dr.-Ing. Professional Life -

Component Analysis of Design and Construction As Housing Acceptability Factor of Public Housing Estates in Anambra State, Nigeria by Architect Dr

Global Journal of Researches in Engineering: E Civil And Structural Engineering Volume 15 Issue 2 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4596 & Print ISSN: 0975-5861 Component Analysis of Design and Construction as Housing Acceptability factor of Public Housing Estates in Anambra State, Nigeria By Architect Dr. Chikadibia Michael Eni Federal Polytechnic, Nigeria Abstract- The thrust of this study was to evaluate the design and construction as a housing acceptability factor of nine public housing estates in Awka and five others in Onitsha towns in Anambra State using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) method. The universe of the study consisted of 2,805 housing units in Awka and Onitsha by house type and 2,955 occupants including 50 persons each from Anambra State Housing Development Corporation/Anambra Homeownership Company Limited (ASHDC/ AHOCOL), Non Estate Occupiers (NEOs) and Private Estate Developers (PEDs) involved. The sample size for the study was 899 which represented 30% of the total population which were drawn using proportionate cluster sampling technique, while 887 were complete responses. One research question and one hypothesis were formulated for the study. An 18-item structured questionnaire (QAHPH) was developed; face and content validated and reliability test was done using Cronbach Alpha Technique index value of 0.90 and pre-tested on a sample of 30 respondents/residents of another housing estate. Keywords: housing acceptability, public housing and Principal component. GJRE-E Classification : FOR Code: 290804 ComponentAnalysisofDesignandConstructionasHousingAcceptabilityfactorofPublicHousingEstatesinAnambraStateNigeria Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of : © 2015. Architect Dr. -

Annual Reports 2014 and Financial Statements

Annual Reports 2014 and Financial Statements construct concept operate ELEVATIONCROSS NORTH SECTION EAST - NORTH procure maintain engineer Holistic Services Julius Berger Nigeria Plc, together with its subsidiaries, offers clients integrated construction solutions. From the initial concept to operation and maintenance, includ- ing design, engineering, procurement and construction, expert staff deliver distinct solutions that meet clients’ individual require ments. The Group’s competitive edge lies in its vertically integrated operations and expansive logistics network. This self-reliant operational strategy provides a strong foundation for ensuring high standards are met and project schedules are achieved, no matter the challenge. Julius Berger Nigeria Plc and its subsidiaries approach each project with a strong spirit of partnership and responsibility. Across its whole value chain, quality and innovation are prioritised to deliver tangible benefits to customers. ELEVATION NORTH Julius Berger Nigeria Plc AR & FS 2014 | Table of Contents Contents Highlights Notes to the Financial Statements Corporate Information 5 General Information 66 Results at a Glance 6 Application of IFRS Standards 67 Notice of Annual General Meeting 8 Significant Accounting Policies 71 Notes 9 Explanatory Notes 89 Corporate Profile 10 Chairman’s Statement 12 Additional Information Board of Directors 20 Statement of Value Added 128 Directors’ Profiles 22 Four-Year Financial Summary 130 Share Capital History 132 Reports to Shareholders Staff Strength 133 Directors’ -

LCSH Section V

V (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) V2 Class (Steam locomotives) Vaca family UF Ryan, Valerie (Fictitious character) USE Class V2 (Steam locomotives) USE Baca family Valerie Ryan (Fictitious character) V838 Mon (Astronomy) Vaca Island (Haiti) V-1 bomb (Not Subd Geog) USE V838 Monocerotis (Astronomy) USE Vache Island (Haiti) UF Buzz bomb V838 Monocerotis (Astronomy) Vaca Muerta Formation (Argentina) Flying bomb This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Formations (Geology)—Argentina FZG-76 (Bomb) subdivision. Geology, Stratigraphic—Cretaceous Revenge Weapon One UF V838 Mon (Astronomy) Geology, Stratigraphic—Jurassic Robot bombs Variable star V838 Monocerotis Vacada Rockshelter (Spain) V-1 rocket BT Variable stars UF Abrigo de La Vacada (Spain) Vergeltungswaffe Eins V1343 Aquilae (Astronomy) BT Caves—Spain BT Surface-to-surface missiles USE SS433 (Astronomy) Spain—Antiquities NT A-5 rocket VA hospitals Vacamwe (African people) Fieseler Fi 103R (Piloted flying bomb) USE Veterans' hospitals—United States USE Kamwe (African people) V-1 rocket VA mycorrhizas Vacamwe language USE V-1 bomb USE Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizas USE Kamwe language V-2 bomb Va Ngangela (African people) Vacanas USE V-2 rocket USE Ngangela (African people) USE Epigrams, Kannada V-2 rocket (Not Subd Geog) Vaaga family Vacancy of the Holy See UF A-4 rocket USE Waaga family UF Popes—Vacancy of the Holy See Revenge Weapon Two Vaagd family Sede vacante Robot bombs USE Voget family BT Papacy V-2 bomb Vaagn (Armenian deity) Vacant family (Not Subd Geog) Vergeltungswaffe Zwei USE Vahagn (Armenian deity) UF De Wacquant family BT Rockets (Ordnance) Vaago (Faroe Islands) Wacquant family NT A-5 rocket USE Vágar (Faroe Islands) Vacant land — Testing Vaagri (Indic people) USE Vacant lands NT Operation Sandy, 1947 USE Yerukala (Indic people) Vacant lands (May Subd Geog) V-12 (Helicopter) (Not Subd Geog) Vaagri Boli language (May Subd Geog) Here are entered works on urban land without UF Homer (Helicopter) [PK2893] buildings, and not currently being used.