Contemporary British Television Crime Drama: Cops on the Box

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINE of DUTY 2 EP2 2013-06-02 Cherry.Fdx Script

LINE OF DUTY 2 Written by Jed Mercurio Episode 2 Pink Shooting Script Dated: 18 April 2013 Blue revisions: 19 April 2013 Yellow revisions: 29 April 2013 Green revisions: 30 April 2013 Gold revisions: 12 May 2013 Buff revisions: 20 May 2013 Salmon revisions: 22 May 2013 Cherry revisions: 2 June 2013 World Productions 101 Finsbury Pavement London EC2A 1RS T. 020 3002 3113 Line of Duty #2.2 02/06/2013 CHERRY revisions 1. PREVIOUSLY ... Mallick tells Lindsay what he thinks of her. MALLICK I’ve got a room full of detectives getting 4’s and 5’s. You’re a 2 at best. CUT TO: Lindsay assaults her next-door-neighbour. LINDSAY I’m. Not. Going. To. Take. It. Any. More. CUT TO: O’Neill comes to grab Lindsay. O’NEILL Call for the Duty Inspector. CUT TO: Lindsay picks up the phone. LINDSAY DI Denton. INTERCUT: CAST CREDIT INTERCUT: Hastings introduces Steve to Georgia. HASTINGS DC Trotman. CUT TO: Steve and Georgia get drunk together. CUT TO: Steve and Georgia snog. INTERCUT: CAST CREDIT INTERCUT: (CONTINUED) Line of Duty #2.2 02/06/2013 CHERRY revisions 2. CONTINUED: Akers hurries the Witness under a blanket from the safe house to the waiting car. CUT TO: Lindsay drives the lead vehicle; Akers’ vehicle follows. CUT TO: The ambush vehicle smashes into the vehicles. Gunmen spray bullets. They set fire to Akers’ vehicle. They’re clearly established wearing thick black jackets and motorcycle helmets. INTERCUT: CAST CREDIT INTERCUT: Hastings briefs Steve and Kate at the Witness’s bedside. HASTINGS He was in Witness Protection. -

'Line of Duty,' Is Unique Cop Show

ARAB TIMES, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Books ‘A Writer Prepares’ Block’s memoir recalls colorful writing career NEW YORK, June 1, (AP): Lawrence Block has fol- lowed many paths during his long career. “With not a few dead end roads among them,” notes the mystery novelist. Best known for his Matthew Scudder and Bernie Rhodenbarr series, Block has released dozens of pop- ular works through Harper Collins and Dutton among other mainstream publishers. He has received multiple Edgar Awards and Anthony Awards for outstanding fi ction, and his lifetime achievement honors include the Diamond Dagger from the British Crime Writers’ Association and Grand Master status in the Mystery Writers of America. But he has also completed dozens of works under other names, by publishers and publications long since forgotten, and, in some cases, of questionable legality. More recently, he has been publish- ing the books himself, includ- ing “Dead Girl Blues” and the Rhodenbarr novel “The Bur- glar In Short Order,” which both came out in 2020, and his current work, the memoir “A Writer Prepares.” “One big plus of self-pub- lishing is how quickly it can be managed. I can reduce waiting Block time by a minimum of a year if I publish something myself,” he explains. “The downside is not to be shrugged off. Self-pub- lished books rarely get reviewed and hardly ever show up in bookstores. ‘Dead Girl Blues’ didn’t make me This image released by BritBox shows Vicky McClure, (left), and Kelly Macdonald in a scene from the BBC police drama series ‘Line of Duty.’ (AP) rich, and neither will ‘A Writer Prepares.’ But nothing I write is going to do that, no matter who publishes it, and whatever I self-publish stays forever available in electronic and print editions, and probably fi nds what- ever audience it deserves to have.” Television Block is a longtime Greenwich Village resident, fully vaccinated and back outside, enjoying a nice big plate of Brussels sprouts during a recent afternoon in- terview at a favorite cafe. -

Falco Mexico and Amazon

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RED ARROW STUDIOS INTERNATIONAL’S HIT SCRIPTED CRIME FORMAT FALCO TO STREAM EXCLUSIVELY ON AMAZON PRIME VIDEO ACROSS LATIN AMERICA Spiral International has signed an agreement with Amazon Prime Video to be the exclusive streaming home in Latin America for new Mexican crime series “FALCO” – an adaptation of Red Arrow Studios International’s hit international crime format “The Last Cop” MUNICH / MIAMI. MARCH 22, 2018: Spiral International, the leading Latin American distributor for Red Arrow Studios International, has signed an agreement with Amazon Prime Video to bring the Mexican adaptation of “FALCO”, based on the acclaimed scripted format “The Last Cop”, exclusively to its streaming service in Latin America. Red Arrow Studios International will also launch the 15 x 1 hour finished tape of “FALCO” (Mexico) at MIPTV 2018. “FALCO” is produced by Spiral International and production powerhouse Dynamo (“Narcos”, “American Made”), and features Michel Brown, star of the International Emmy® award winning series “Sr. Ávila”, in the lead role. The series is showrun and directed by acclaimed Mexican filmmaker, director and screenwriter Ernesto Contreras (“Blue Eyelids”, “I Dream in Another Language”, “The Obscure Spring”, “El Chapo”), who has a total of 19 International Film Festival Wins and 9 Nominations. In “FALCO”, it’s 1994 in Mexico City, and Alejandro Falco is a reputable policeman with a promising future and a young family. However, his perfect world is shattered when he is shot by a mysterious attacker in the line of duty. With a bullet lodged in his head, Falco falls into a coma – for the next 24 years. -

Gender Dynamics in TV Series the Fall: Whose Fall Is It? Adriana Saboviková, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovakia1

Gender Dynamics in TV Series The Fall: Whose fall is it? Adriana Saboviková, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovakia1 Abstract This paper examines gender dynamics in the contemporary TV series The Fall (BBC 2013 - 2016). This TV series, through its genre of crime fiction, represents yet another way of introducing a strong female character in today’s postfeminist culture. Gillian Anderson’s Stella Gibson, a Brit and a woman, finds herself in the men’s world of the Police Service in Belfast, where the long shadow of the Troubles is still present. The paper proposes that the answer to the raised question - who the eponymous fall (implied in the name of the series) should be attributed to - might not be that obvious, while also discussing The Fall’s take on feminism embodied in its female lead. Keywords: female detectives, The Fall, TV crime drama, postfeminism Introduction Troubled history is often considered to be the reason for Northern Ireland being described as a nation of borderlines - not only obvious physical ones but also imagined. This stems from the conflict that has been described most commonly in terms of identities - based on culture, religion, and even geography. The conflict that has not yet been completely forgotten as the long shadow of the Troubles (local name, internationally known as the Northern Ireland conflict) is still present in the area. Nolan and Hughes (2017) describe Northern Ireland as “living apart together” separated by physical barriers. These locally called peace walls had to be erected to separate and, at the same time, protect the communities. -

Michael Keillor Writer/Director

Michael Keillor Writer/Director Michael’s passion for bold and ambitious projects has drawn him to work with a talented mix of writers who share his appetite for pushing boundaries while entertaining audiences. Most recently Michael directed David Hare’s four-part political drama ROADKILL, which captured the world-weary mood of 2020, charting the rise of a corrupt and self-serving politician played with ruthless charisma and impeccable charm by Hugh Laurie. Agents Michelle Archer Assistant Grace Baxter [email protected] 020 3214 0991 Credits Television Production Company Notes ROADKILL The Forge/PBS/BBC 1 Director and Executive Producer 2020 4-part Drama. Writer: David Hare. Producer: Andy Litvin Exec Producers: George Faber, Mark Pybus, Lucy Richer, David Hare, Michael Keillor. Starring: Hugh Laurie, Helen McCrory, Pippa Bennett Warner, Sarah Greene, Sidse Babett Knudsen, Iain De Caestecker. Popular and charismatic politician Peter Laurence is shamelessly untroubled by guilt or remorse as his public and private life fall apart. *Winner, Original Music Bafta Craft Awards 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes CHIMERICA Playground Director 2018 - 2019 Entertainment/Channel 4 4-part Drama. Writer: Lucy Kirkwood. Producer: Adrian Sturges. Executive Producers: Lucy Kirkwood, Sophie Gardiner, Colin Callender. Starring: Alessandro Nivola and Cherry Jones A photojournalist travels to China with the hopes of finding out who the mysterious man was who was photographed standing defiantly in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square twenty years ago. Adaptation of the Olivier award-winning play. -

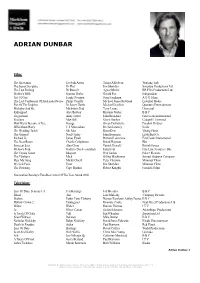

Adrian Dunbar

ADRIAN DUNBAR Film: The Snowman Frederik Aasen Tomas Alfredson Working Title The Secret Scripture Dr Hart Jim Sheridan Scripture Productions Ltd The Last Furlong Dr Russell Agnes Merlet RR Film Productions Ltd Mother's Milk Seamus Dorke Gerald Fox Independent Act Of God Frank O'connor Sean Faughnan A O G Films The Last Confession Of Alexander Pearce Philip Conolly Michael James Rowland Essential Media Eye Of The Dolphin Dr James Hawk Michael D.sellers Quantum Entertainment Mickybo And Me Mickybo's Dad Terry Loane Universal Kidnapped Alex Balfour Brendan Maher B B C Triggerman Andy Jarrett John Bradshaw First Look International Shooters Max Bell Glenn Durfort Catapult / Universal How Harry Became A Tree George Goran Paskaljevic Paradox Pictures Wild About Harry J. J. Macmohan Declan Lowney Scala The Wedding Tackle Mr. Mac Rami Dvir Viking Films The General Noel Curley John Boorman Little Bird Co. Richard Iii James Tyrell Richard Loncraine First Look International The Near Room Charlie Colquhoun David Hayman Bbc Innocent Lies Alan Cross Patrick Dewolf British Screen Widow's Peak Godfrey Doyle-counihan John Irvin Fine Line Features / Bbc The Crying Game Maguire Neil Jordan Palace Pictures The Playboys Mick Gillies Mackinnon Samuel Godwyn Company Hear My Song Micky O'neill Peter Chelsom Miramax Films My Left Foot Peter Jim Sheridan Miramax Films The Dawning Capt. Rankin Robert Knights Ferndale Films Nomination Barclay's Tma Best Actor Of The Year Award 2002 Television: Line Of Duty, Seasons 1-5 Ted Hastings Jed Mecurio B B C Blood Jim Lisa -

ITV on Track to Deliver

Interim Results 2017 ITV plc ITV on track to deliver Interim results for the six months to 30 June 2017 Peter Bazalgette, ITV Executive Chairman, said: “ITV’s performance in the first six months of the year is very much as we anticipated and our guidance for the full year remains unchanged. “Total external revenue was down 3% with the decline in NAR partly offset by continued good growth in non-advertising revenues, which is a clear indication that our strategy of rebalancing the business is working. We are confident in the underlying strength of the business as we continue to invest both organically and through acquisitions. “ITV Studios total revenues grew 7% to £697m including currency benefit. ITV Studios adjusted EBITA was down 9% at £110m. This was impacted by our ongoing investment in our US scripted business and the fact that the prior year includes the full benefit of the four year license deal for The Voice of China. We have a very strong pipeline of new and returning drama and formats and we are building momentum in our US scripted business. We continue to grow our global family of production companies and in H1 we further strengthened our international drama and format business with the acquisition of Line of Duty producer World Productions in the UK, Tetra Media Studio in France and Elk Production in Sweden. “The Broadcast business remains robust despite the 8% decline in NAR caused by ongoing economic and political uncertainty with Broadcast & Online adjusted EBITA down 8% at £293m. On-screen we are performing well. -

Britbox Stars Talk About What Tv Moved, Amused and Inspired Them

BRITBOX STARS TALK ABOUT WHAT TV MOVED, AMUSED AND INSPIRED THEM JAMES NESBITT The Cold Feet actor’s top picks on BritBox: ● Cracker ● Prime Suspect ● Boys From The Blackstuff ● Black Adder ● Fawlty Towers ● The Good Life ● The Two Ronnies ● The Young Ones “The notion of being part of a new platform that really does try and bring different genres together but all underscored by a certain quality is very exciting.” Is there anything you watched growing up that you have great memories of? I first really recall, in terms of drama, Boys From The Blackstuff. I thought it was just extraordinary. And The Monocled Mutineer. A lot of those programmes really gripped me. I also grew up watching a lot of comedy with my mum actually. Fawlty Towers was must see. I was quite young for that but I immediately understood the absurdity, the pain of it, the farce. The Two Ronnies I used to love. My mum actually looked a bit like Ronnie Corbett which was a bit odd! I also grew up watching sport and still love Match of The Day. To grow up on all those dramas and now to be part of it has been one of the great journeys to be honest. Can you tell us why you were interested in getting involved in the launch of BritBox? Television has been very, very good to me. I’ve been working for a long time now. I’m one of those people who people think is the youngest on set but I’m by far the oldest! I’ve been working since I left drama school in 1988. -

K7 UK Scripted Report Thursday 24 June 2021 2

K7 UK Scripted Report Thursday 24 June 2021 A comprehensive weekly overview of comedy and drama programming in the UK. The North Water Produced by See-Saw Films. Rhombus Media are co-producing K7.Media K7 UK Scripted Report Thursday 24 June 2021 New Commissions and In Development DRAMA • Playground Entertainment has acquired the rights to George Simenon’s Inspector Maigret detective stories. The Colin Callender-owned indie will co-develop a premium returning drama series based on the stories along with Red Arrow Studios International. Updates DRAMA • Filming has begun on Amazon's six-part thriller The Devil's Hour, with Jessica Raine (Patrick Melrose) and Peter Capaldi (Doctor Who) leading the cast. Produced by Hartswood Flims. • Peaky Blinders director Otto Bathurst has come on board to direct BlackBox Multimedia and Stone Village's new adaptation of Frankenstein, with his company One Big Picture co-producing. • BBC2 has released first look images for its adaptation of Ian McGuire's thriller The North Water. Produced by See-Saw Films. Rhombus Media are co-producing. • ITV has released a series of first-look images for its six-part thriller Trigger Point which follows the Metropolitan Police Service’s Bomb Disposal Squad. The series hails from Line Of Duty creator Jed Mercurio and will star Vicky McClure (Line Of Duty). Produced by HTM Television and Hat Trick Productions. COMEDY • Further casting has been announced for ITV's comedy drama The Larkins which is based on H.E. Bates’ novel The Darling Buds of May. Produced by Objective Fiction, Genial Productions and Objective Media Group Scotland in association with All3Media International. -

GO357 Line of Duty Death

GREELEY POLICE DEPARTMENT General Order 357.00 Reviewed: 01/19 357.00 LINE OF DUTY DEATH 357.01 Definitions: Line-of-Duty Death: Any action, felonious, accidental or natural, which claims the life of a Greeley Police Officer who is performing work-related functions either while on or off duty. Survivors: Immediate family members of the deceased officer: spouse, children, parents, siblings, fiancée, and/or significant others. Beneficiary: Those designated by the officer as recipient(s) of specific death benefits. Benefits: Financial payments made to the family to insure financial stability following the loss of a loved one. Funeral Payments: Financial payments made to the surviving family of an officer killed in the line-of-duty, which are specifically earmarked for funeral expenses. 357.02 Procedures and Responsibilities: It shall be the responsibility of the Chief of Police or a Deputy Chief (NOTIFICATION OFFICER) in cooperation with the Coroner’s Office to properly notify the next of kin of an officer who has suffered severe injuries or died. The name of the deceased officer must NEVER be released by the department before the survivors are notified. If there is knowledge of a medical problem with an immediate survivor, medical personnel should be available at the residence to coincide with the death notification. The family should learn of the death from the department first and not from the press or other sources. If there is an opportunity to get to the hospital prior to the demise of the officer, DO NOT wait. If the family requests to visit the hospital, they should be transported by police department vehicle. -

Best Shows Streaming Right

The best shows streaming right now Including WandaVision Succession I Hate Suzie Staged Normal People Small Axe Fantastic shows at your fingertips THERE HAS NEVER been a better time to find your new favourite show, with more content available at the press of a button or the swipe of a screen than ever before. Traditional broadcasters continue to add more shows to their catch-up services every day while a raft of new subscription streaming services has flooded the TV market, bringing us a wealth of gripping dramas, out-of-this-world sci-fi, insightful docs and exciting entertainment formats. But with such a vast choice available, it can sometimes feel overwhelming. But never fear, our expert editors have done the hard work for you, selecting 50 of the very best shows designed to suit every taste that you can watch right now. So sit back, stop scrolling and start watching great TV… Tim Glanfield Editorial Director RadioTimes.com The Last Kingdom FOR HALF A decade fans have been gripped by The Last Kingdom, an epic drama that follows noble warrior Uhtred of Bebbanburg in the dangerous years prior to the formation of England. Based on the novels by Bernard Cornwell (Sharpe), this series blends fact and fiction to create an action-packed medieval saga that rivals Game of Thrones. Alexander Dreymon is electric in the lead role and the series is at its strongest when his fierce fighter shares the screen with David Dawson’s pious King Alfred (later to be known as “the Great”). With a brisk pace across four seasons, it boasts shocking twists and bitter rivalries. -

Mary Finlay- Film Editor

AMANDA McALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44 (0) 207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] MARY FINLAY- FILM EDITOR www.maryfinlay.com FEATURE CREDITS INCLUDE: MY SALINGER YEAR Director Philippe Falardeau Coming of Age Memoir Producers Ruth Coady, Luc Déry, Kim McCraw, Sue Mullen Locations: Ireland, Montreal Featuring Sigourney Weaver, Margaret Qualley Production Co. micro_scope, Parallel Films OPENING BERLIN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2020 ON WINDMILL LANE Director Alan Moloney Historical Music Feature Documentary Producer Ruth Coady Location: Ireland Production Co. Animo TV SNAP Director Carmel Winters Drama Producer Martina Niland, Exec Producer David Collins Featuring Aisling O’Sullivan, Eileen Walsh Production Co. Samson Films THE WEDDING DATE Director Clare Kilner Comedy Romance Producers Paul Brooks, Mairi Brett Featuring Debra Messing, Dermot Mulroney Production Co. Gold Circle Films / Universal Pictures ABOUT ADAM Director Gerard Stembridge Comedy Romance Producers Anna Devlin, Marina Hughes Featuring Kate Hudson, Stuart Townsend, Frances O’Connor Production Co. BBC Films / Miramax GRAND THEFT PARSONS Director David Caffrey Adventure Comedy Drama Producer Frank Mannion Featuring Johnny Knoxville, Michael Shannon Production Co. Swipe Films I REALLY HATE MY JOB Director Oliver Parker Drama Producers Andrew Higgie, Matthew Justice Featuring Neve Campbell, Anna Maxwell-Martin, Danny Huston Production Co. 3DD Productions JANICE BEARD: 45WPM Director Clare Kilner, Producer Judy Counihan Comedy Exec. Producer Jonathan Olsberg Featuring Eileen Walsh, Rhys Ifans Production Co. Dakota Films / The Film Consortium NINA’S HEAVENLY DELIGHTS Director Pratibha Parmar Drama Producers Chris Atkins, Marion Pilowsky Exec. Producers Margaret Matheson, Claire Chapman, Scott Meek Featuring Laura Fraser, Shelley Conn, Art Malik Production Co.