Shakespeare's Penknife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

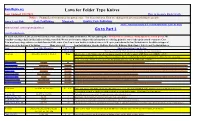

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

Ln //-----~-----__M---)~ 02-0&31 Hunting Knife

ADDISON BUILDING MATERIAL CO. INC., • 3201 S. Busse Rd., Arlington Heights, IL 60005 Order Department (847) 437-1288· Main (847) 437-1205 • FAX (847) 437-4183 91 Ka.-ba~ SKU NO. 700910 02-G603 3-5116" III Standard Barlow knife, clip and pen blades. SKU NO. 701010 02-0644 4" Stock knife; clip, coping and spey blades. SKU NO. 700920 02-0&05 3-3116" Serpentine Jackknife, clip and pen blades. I=--- SKU NO. ~_ ~-~701015 02-1l646 Closed size 3-15/16", open size 7-1/8", dark brown handle. SKU NO. 700t35 02-0&19 3-11N6" Camping knife; spear, can opener, screwdriver/ SKU NO. bottle opener, punch blades with shackle. 701037 02-0647 Closed size 3", open size 5-1/2", dark brown handle. SKU NO. 700950 02-0&29 5" Daddy Barlow, clip blade. SKU NO. c~~701039 02-0648 Closed size 4", ~ ....-...'\!t:!~~ open size 7-1/8", maroon handle. Ln_//-----~-----__m---)~ 02-0&31 Hunting knife. Bowie style, 6'" blade with sheath. Stainless steel blade, genuine hardwood handle. SKU NO. 700985 SKU NO. 70104302·1013 3%W BARLOW - Clip and pen blades. ~ SKU NO. 700195 02-0&35 3-3116" Pearlized Jackknife. Clip and pen blades. SKU NO. 701049 02-1026 3w JACK KNIFE - Clip and pen blades. SKU NO. 701000 02-0&37 2-518" Penknife. Clip and pen blades. RENTAL' BUILDING MATERIALS' HAND TOOLS· POWER TOOLS· HARDWARE· FASTENERS· PAINT· ELECTRICAL' PLUMBING· LAWN & GARDEN· JANITORIAL ADDISON BUILDING MATERIAL CO. INC., • 3201 S. Busse Rd., Arlington Heights, IL 60005 92 Order Department (847) 437-1288· Main (847) 437-1205· FAX (847) 437-4183 02-1342 43~" SHEATH - Brown Oil Finished Leather Sheath with stitched belt loop on back. -

Chapter Seven Study Questions

Chapter Seven Study Questions 2. Synonyms 1) change, alter, vary, modify mean to make or become different. Change implies making either an essential difference often amounting to a loss of original identity or a substitution of one thing for another <changed the shirt for a larger size>. Alter implies the making of a difference in some particular respect without suggesting loss of identity <slightly altered the original design>. Vary stresses a breaking away from sameness, duplication, or exact repetition <you can vary the speed of the conveyor belt>. Modify suggests a difference that limits, restricts, or adapts to a new purpose <modified the building for use by the handicapped>. 2) hate, detest, abhor, abominate, loathe mean to feel strong aversion or intense dislike for. Hate implies an emotional aversion often coupled with enmity or malice <hated his former friend with a passion>. Detest implies violent antipathy or dislike, but without active hostility or malevolence <I detest moral cowards>. Abhor implies a deep, often shuddering repugnance from or as if from fear or terror <child abuse is a crime abhorred by all>. Abominate suggests strong detestation and often moral condemnation <virtually every society abominates incest>. Loathe implies utter disgust and intolerance <loathed self-appointed moral guardians>. 3) repugnant, repellent, abhorrent, distasteful, obnoxious, invidious mean so unlikable as to arouse antagonism or aversion. Repugnant applies to something that is so alien to one’s ideas, principles, tastes as to arouse resistance or loathing <regards boxing as a repugnant sport>. Repellent suggests a generally forbidding or unpleasant quality that causes one to back away <the public display of grief was repellent to her>. -

Sir Robert Sidney's Poems Revisited

Sir Robert Sidney’s Poems Revisited: the Alternative Sequence Maria de Jesus Crespo Candeias Velez Relvas UNIVERSIDADE ABERTA DE PORTUGAL For the last five or six years, and for some different occasions, I have had the opportunity, and the pleasure, of dedicating myself to the study of Sir Robert Sidney’s poetic work. This “revisitation” is primarily motivated by the fact that, as far as I know, The Poems keep being neglected by the potential readers but also because the text keeps offering varied possibilities of analysis, further paths to be explored. After the rediscovery of the corpus in 1973 and its publication in 1984, Mr P. J. Croft’s own excellent critical edition,1 and some articles (all of them enthusiastic, I must say) by a few scholars,2 constitute the only approaches to the work. I strongly believe that this new voice from the Elizabethan golden age, that has brought new and important elements to our perspective of the time, should not be forgotten. Therefore, I cannot understand or accept the criteria adopted by the editors of a very recent anthology of poetry, who selected a wide range of works written by Elizabethan and Jacobean authors, even by some anonymous ones, and did not publish a single composition of Robert Sidney. Besides the interest of the poems, his sequence discloses relevant peculiarities: it is the longest autograph manuscript from the period discovered until now, contained in a bound notebook which survived complete and admirably preserved for four centuries, exhibiting the unity, revisions, corrections and organisation outlined by the poet himself. -

Swift's Razor

Swift's razor Article Accepted Version Bullard, P. (2016) Swift's razor. Modern Philology, 113 (3). pp. 353-372. ISSN 0013-8304 doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/684098 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/53023/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/684098 Publisher: University of Chicago Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online SWIFT’S RAZOR PADDY BULLARD University of Reading I am afraid lest such a Practitioner, with a Body so open, so foul, and so full of Sores, may fall under the Resentment of an incensed political Surgeon, who is not in much Renown for his Mercy upon great Provocation: Who, without waiting for his Death, will flay and dissect him alive; and to the View of Mankind, lay open all the disordered Cells of his Brain, the Venom of his Tongue, the Corruption of his Heart, and Spots and Flatuses of his Spleen — and all this for Three-Pence.1 The “Practitioner” described in these furious lines is a half-forgotten Irish politician of the eighteenth century called Joshua, Viscount Allen. The “incensed political Surgeon” is more easily recognized: he is Jonathan Swift, preparing with his usual relish for a familiar satirical operation. -

Transforming the Petrarchan Tradition in the Poetry of Lady Mary Wroth (1587–1631)

Prague Journal of English Studies Volume 5, No. 1, 2016 ISSN: 1804-8722 (print) '2,10.1515/pjes-2016-0001 ISSN: 2336-2685 (online) “The True Forme of Love”: Transforming the Petrarchan Tradition in the Poetry of Lady Mary Wroth (1587–1631) Tomáš Jajtner e following article deals with the transformation of the Petrachan idea of love in the work of Lady Mary Wroth (1587-1631), the fi rst woman poet to write a secular sonnet sequence in English literature, Pamphilia to Amphilanthus. e author of the article discusses the literary and historical context of the work, the position of female poets in early modern England and then focuses on the main diff erences in Wroth’s treatment of the topic of heterosexual love: the reversal of gender roles, i.e., the woman being the “active” speaker of the sonnets; the de-objectifying of the lover and the perspective of love understood not as a possessive power struggle, but as an experience of togetherness, based on the gradual interpenetration of two equal partners. Keywords Renaissance English literature; Lady Mary Wroth; Petrarchanism; concept of love; women’s poetry 1. Introduction “Since I exscribe your Sonnets, am become/A better lover, and much better Poët”. ese words written by Ben Jonson and fi rst published in his Workes (1640) point out some of the fascination, as well as a sense of the extraordinary, if not downright oddity of the poetic output of Lady Mary Wroth (1587-1631), the niece of Sir Philip Sidney and daughter of another English Renaissance poet, Sir Robert Sidney, the fi rst Earl of Leicester (1563-1626). -

For the Rigours of Modern Life

FOR THE RIGOURS OF MODERN LIFE OUTDOORS | TOOLS & GADGETS | HOME OFFICE | BARWARE | KITCHENWARE | ACCESSORIES | SUPERIOR GROOMING SS18 Born out of a passion for building superior, durable, responsible goods that equip modern gentlemen for the rigours of life. From multi-tools to gadgets, grooming accessories, outdoor enamelware, barware, kitchenware and more, our products are crafted by relentless pioneers who share an unfaltering commitment to quality, function and style. OUTDOORS 04-15 BARWARE KITCHENWARE 26-29 30-33 TOOLS & GADGETS HOME OFFICE 16-23 24-25 ACCESSORIES SUPERIOR GROOMING 34-41 42-45 From forest treks to eating alfresco, or camping under the stars, this functional and stylish range will ensure you have the tools needed in the great outdoors. OUTDOORS 4 GENTLEMEN’S HARDWARE NEW Campfi re Poker NEW Campfi re Games NEW Campfi re Survival Cards Campfi re Poker set with 52 waterproof playing Campfi re Games set with 52 waterproof 52 fully illustrated waterproof playing cards, 120 metal bottle cap poker chips and playing cards, 6 dice, score pad, pencil cards with survival facts and tips. instructions for Texas Hold’Em. and dice game instructions. Box Size: 85 x 105 x 21mm Box Size: 122 x 110 x 40mm Box Size: 122 x 110 x 40mm GEN165 English GEN173 GEN243 GEN188 French Pocket Ground Sheet Travel Towel NEW Hurricane Lamp Lightweight and compact Pocket Ground Lightweight quick-dry microfi bre Travel Towel. Vintage-inspired Hurricane Lamp in matte red Sheet made from durable ripstop. Folds up Folds to a small size. and chrome. Includes 15 energy effi cient LED into a compact bag with carabiner. -

Exploring Shakespeare's Sonnets with SPARSAR

Linguistics and Literature Studies 4(1): 61-95, 2016 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2016.040110 Exploring Shakespeare’s Sonnets with SPARSAR Rodolfo Delmonte Department of Language Studies & Department of Computer Science, Ca’ Foscari University, Italy Copyright © 2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Shakespeare’s Sonnets have been studied by rhetorical devices. Most if not all of these facets of a poem literary critics for centuries after their publication. However, are derived from the analysis of SPARSAR, the system for only recently studies made on the basis of computational poetry analysis which has been presented to a number of analyses and quantitative evaluations have started to appear international conferences [1,2,3] - and to Demo sessions in and they are not many. In our exploration of the Sonnets we its TTS “expressive reading” version [4,5,6]1. have used the output of SPARSAR which allows a Most of a poem's content can be captured considering full-fledged linguistic analysis which is structured at three three basic levels or views on the poem itself: one that covers macro levels, a Phonetic Relational Level where phonetic what can be called the overall sound pattern of the poem - and phonological features are highlighted; a Poetic and this is related to the phonetics and the phonology of the Relational Level that accounts for a poetic devices, i.e. words contained in the poem - Phonetic Relational View. -

Knives, Scouts and the Law

Knives, Scouts and the Law Criminal Justice Act 1988. The Act details what is generally deemed to be an ‘offensive’ weapon and Section 139 particularly describes what types of knives are banned, those that can be carried in public and under what circumstances. The law in a nutshell Buying/selling knives • It is illegal for any shop to sell a knife of any kind (including cutlery, kitchen knives, Swiss army knives or axes) to anyone under the age of 18 Carrying knives • In general, it is an offence to carry a knife in a public place without good reason or lawful authority for example, a good reason is a chef on their way to work and carrying their own knives). • However, it is not illegal for anyone to carry a foldable, non-locking knife, such as a Swiss army knife, in a public place, as long as the blade is shorter than three inches (7.62cms). • Flick knives, butterfly knives and any other knife where the blade is hidden are illegal • If it locks open then the entire knife including the handle must be under 3" long. Knives and Scouts • Knives should be carried to and from meetings by an adult. • Knives should be stowed in the middle of a bag/rucksack when transporting. • Knives are tools and should be treated as such: use the appropriate tool for the job (don’t use a large fixed blade for carving or a penknife for clearing brush). • Knives should be stored away until there is a need for them to be used. -

C-190.1 - Whittling Chip 101

C-190.1 - Whittling Chip 101 John Lewis November 3 ,2018 Items to Cover • Introductions • Whittling Chip for Cub Scouts • Types of Knives • Safe Handling and General Knife Safety • Caring for Your Knife • Pocket Knife Pledge • Knife Safety Quiz • Soap Carving Exercise • Carving Ideas • Supplemental / Additional Resources • Knife Safety Quiz Answers 11/14/2018 2 Introductions • Your instructors • Intent of course • Introduce yourself • Name • Scouting experience • Pocket knife experience and knowledge • Have you ever sharpened a knife on a stone before? • Have you ever carved something before? 11/14/2018 3 Whittling Chip for Cub Scouts • Earned during the Bear year • One of the key milestones during Cub Scout years that the boys look forward to completing • Requires a basic set of dexterity, maturity and understanding of safety • As responsible leaders and adults, we must properly teach and monitor our boys • Make sure the boys understand the consequences of misuse – cutting corner of Whittling Chip card for egregious violations, temporary suspension of knife privileges, 4 cut corners and you have to redo the requirements • Starting with plastic knives or using the lipstick on the blade exercise 11/14/2018 4 Types of Knives • First, a knife is a tool, not a toy! • 3 basic designs Cubs can use • Jackknife – 1-2 blades hinged at one end of knife body • Penknife – 2 or more blades hinged at both end of the knife body • Multipurpose knife – 1 or more blades along with various tools (scissors, leather punch, etc.) • Other designs, such as fixed -

STACKED DUPLEXES a Publlcation of the Net{ Haven Preservatlon Trust

STACKED DUPLEXES A Publlcation of The Net{ Haven Preservatlon Trust INTRODUCTION l.lHAT IS A STACKED DUPLEX? During the past decade, interest in older residential In its purest form, a Stacked Duplex is a large, bui ldinss in Connecticut's urban neighborhoods has gable-fronted, freestanding wooden box containing experienced a great revivai. Urban renewal programs of virtual ly identical two-room wide, four-room deep, the 1950s and 1960s, which typically ignored or cate- first- and second-story apartments, Typical iy this gorized oider buildings as obsolete Iiabilities best buiidins type has a large attic formed by a steeply dealt with through replacement, have gradually given pitched gable roof, and a two-story front porch. t,lay to revitalization programs focusing on the rehab- iiitation 0f these same buiidinss. This change in As a group, Stacked Duplexes feature a broad range of attitude has been fostered by a number of factors, variati0ns on this basic theme, Some are built of includinq an increasing recogniti0n that (a) oider brick, others of concrete block; some have cross-gable residential buiidinss make an important contributi0n roofs, others have gable r0ofs topped by iarge inter- to the special "historic" character of a city and its secting gaole dormers, some have narrow pr0jecting neishborhoods; (b) buildinss of this type often exhi- side l.iings or turrets, others have simple rectangular bit a levei of excel lence in craftsmanship whicn is overal I plans; some have projecting wlndow bays, rareiy found in modern buildings; and (c) rehabilita- others do not; some feature extensive and elaborate tion of oider residential bui ldinss is increasingiv exterior ornamentati0n, others have exteriors I4hich becoming an affordable and productive investment for are very plain. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Protestant Reformation and the English Amatory Sonnet Sequence: Seeking Salvation in Love Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/16m3x3z4 Author Shufran, Lauren Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION AND THE ENGLISH AMATORY SONNET SEQUENCE: SEEKING SALVATION IN LOVE POETRY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Lauren Shufran June 2017 The Dissertation of Shufran is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Sean Keilen, chair ____________________________________ Professor Jen Waldron ____________________________________ Professor Carla Freccero _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Lauren Shufran 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: “Till I in hand her yet halfe trembling tooke”: Justification in Edmund Spenser’s Amoretti 18 Chapter 2: Thomas Watson’s Hekatompathia: Reformed Grace and the Reason-versus-Passion Topos 76 Chapter 3: At Wit’s End: Philip Sidney and the Postlapsarian Limits of Reason and Will 105 Chapter 4: “From despaire to new election”: Predestination and Astrological Determinism in Fulke Greville’s Caelica 165 Chapter 5: Mary Wroth’s “strang labourinth” as a Predestinarian Figure in Pamphilia to Amphilanthus 212 Chapter 6: Bondage of the Will / The Bondage of Will: Theological Traces in Shake-speares Sonnets 264 iii ABSTRACT THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION AND THE ENGLISH AMATORY SONNET SEQUENCE: SEEKING SALVATION IN LOVE POETRY Lauren Shufran When he described poetry as that which should “delight to move men to take goodnesse in hand,” Philip Sidney was articulating the widely held Renaissance belief that poetry’s principal function is edification.