Third Party Liability of the Private Space Industry: to Pay What No One Has Paid Before

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astra Space, Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): August 27, 2021 Astra Space, Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 001-39426 14-1916687 (State or Other Jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of Incorporation) Identification No.) 1900 Skyhawk Street Alameda, California 94501 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (866) 278-7217 Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trading Title of each class Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Class A common stock, par value $0.0001 per share ASTR NASDAQ Global Select Market Warrants to purchase one share of common stock, each at ASTRW NASDAQ Global Select Market an exercise price of $11.50 Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§ 230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§ 240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

GB-ASTRA 3B-Comsatbw-21Mai V

A BOOST FOR SPACE COMMUNICATIONS SATELLITES For its first launch of the year, Arianespace will orbit two communications satellites: ASTRA 3B for the Luxembourg-based operator SES ASTRA, and COMSATBw-2 for Astrium as part of a contract with the German Ministry of Defense. The choice of Arianespace by leading space communications operators and manufacturers is clear international recognition of the company’s excellence in launch services. Because of its reliability and availability, the Arianespace launch system continues to set the global standard. Ariane 5 is the only commercial satellite launcher now on the market capable of simultaneously launching two payloads. Over the last two decades, Arianespace and SES have developed an exceptional relationship. ASTRA 3B will be the 33rd satellite from the SES group (Euronext Paris and Luxembourg Bourse: SESG) to have chosen the European launcher. SES ASTRA operates the leading direct-to-home TV broadcast system in Europe, serving more than 125 million households via DTH and cable networks. ASTRA 3B was built by Astrium using a Eurostar E 3000 platform, and will weigh approximately 5,500 kg at launch. Fitted with 60 active Ku-band transponders and four Ka-band transponders, ASTRA 3B will be positioned at 23.5 degrees East. It will deliver high-power broadcast services across all of Europe, and offers a design life of 15 years. Astrium chose Arianespace for the launch of two military communications satellites, COMSATBw-1 and COMSATBw-2, as part of a satellite communications system supplied to the German Ministry of Defense. The first satellite in this family, COMSATBw-1, was launched by Arianespace in October 2009. -

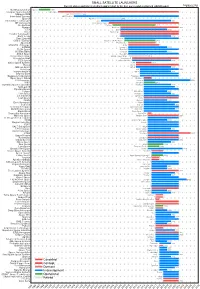

Small Satellite Launchers

SMALL SATELLITE LAUNCHERS NewSpace Index 2020/04/20 Current status and time from development start to the first successful or planned orbital launch NEWSPACE.IM Northrop Grumman Pegasus 1990 Scorpius Space Launch Demi-Sprite ? Makeyev OKB Shtil 1998 Interorbital Systems NEPTUNE N1 ? SpaceX Falcon 1e 2008 Interstellar Technologies Zero 2021 MT Aerospace MTA, WARR, Daneo ? Rocket Lab Electron 2017 Nammo North Star 2020 CTA VLM 2020 Acrux Montenegro ? Frontier Astronautics ? ? Earth to Sky ? 2021 Zero 2 Infinity Bloostar ? CASIC / ExPace Kuaizhou-1A (Fei Tian 1) 2017 SpaceLS Prometheus-1 ? MISHAAL Aerospace M-OV ? CONAE Tronador II 2020 TLON Space Aventura I ? Rocketcrafters Intrepid-1 2020 ARCA Space Haas 2CA ? Aerojet Rocketdyne SPARK / Super Strypi 2015 Generation Orbit GoLauncher 2 ? PLD Space Miura 5 (Arion 2) 2021 Swiss Space Systems SOAR 2018 Heliaq ALV-2 ? Gilmour Space Eris-S 2021 Roketsan UFS 2023 Independence-X DNLV 2021 Beyond Earth ? ? Bagaveev Corporation Bagaveev ? Open Space Orbital Neutrino I ? LIA Aerospace Procyon 2026 JAXA SS-520-4 2017 Swedish Space Corporation Rainbow 2021 SpinLaunch ? 2022 Pipeline2Space ? ? Perigee Blue Whale 2020 Link Space New Line 1 2021 Lin Industrial Taymyr-1A ? Leaf Space Primo ? Firefly 2020 Exos Aerospace Jaguar ? Cubecab Cab-3A 2022 Celestia Aerospace Space Arrow CM ? bluShift Aerospace Red Dwarf 2022 Black Arrow Black Arrow 2 ? Tranquility Aerospace Devon Two ? Masterra Space MINSAT-2000 2021 LEO Launcher & Logistics ? ? ISRO SSLV (PSLV Light) 2020 Wagner Industries Konshu ? VSAT ? ? VALT -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY HAER FL-8-B BUILDING AE HAER FL-8-B (John F. Kennedy Space Center, Hanger AE) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY BUILDING AE (Hangar AE) HAER NO. FL-8-B Location: Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Industrial Area, Brevard County, Florida. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: E 540610 N 3151547, Zone 17, NAD 1983. Date of Construction: 1959 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Present Use: Home to NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) and the Launch Vehicle Data Center (LVDC). The LVDC allows engineers to monitor telemetry data during unmanned rocket launches. Significance: Missile Assembly Building AE, commonly called Hangar AE, is nationally significant as the telemetry station for NASA KSC’s unmanned Expendable Launch Vehicle (ELV) program. Since 1961, the building has been the principal facility for monitoring telemetry communications data during ELV launches and until 1995 it processed scientifically significant ELV satellite payloads. Still in operation, Hangar AE is essential to the continuing mission and success of NASA’s unmanned rocket launch program at KSC. It is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration as Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) original Mission Control Center for its program of unmanned launch missions and under Criterion C as a contributing resource in the CCAFS Industrial Area Historic District. -

INVESTOR PRESENTATION JANUARY 2021 February 2, 2021

INVESTOR PRESENTATION JANUARY 2021 February 2, 2021 PROPRIETARY & CONFIDENTIAL – DO NOT REDISTRIBUTE DISCLAIMER AND FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS This presentation (this “Presentation”) was prepared for informational purposes only to assist interested parties in making their own evaluation of the proposed transaction (the “Transaction”) between Holicity Inc. (“HOL”, “we”, or “our”) and Astra Space, Inc. (“Astra”). By accepting this Presentation, each recipient agrees: (i) to maintain the confidentiality of all information that is contained in this Presentation and not already in the public domain; and (ii) to use this Presentation for the sole purpose of evaluating Astra. This Presentation is for strategic discussion purposes only and does not constitute an offer to purchase nor a solicitation of an offer to sell shares of HOL, Astra or any successor entity of the Transaction. This presentation is incomplete without reference to, and should be viewed solely in conjunction with, the oral briefing provided by HOL. This Presentation is not intended to form the basis of any investment decision by the recipient and does not constitute investment, tax or legal advice. No representation, express or implied, is or will be given by HOL, Astra or their respective affiliates and advisors as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, or any other written or oral information made available in the course of an evaluation of the Transaction. This Presentation and the oral briefing provided by HOL or Astra may contain certain “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, Section 27A of the Securities Act and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, including statements regarding HOL’s, Astra’s on their management teams’ expectations, hopes, beliefs, intentions or strategies regarding the future. -

Space Transportation Atlas V / Auxiliary Payload Overview Space

SpaceSpace TransportationTransportation AtlasAtlas VV // AuxiliaryAuxiliary PayloadPayload OverviewOverview LockheedLockheed MartinMartin SpaceSpace SystemsSystems CompanyCompany JimJim EnglandEngland (303)(303) 977-0861977-0861 ProgramProgram Manager,Manager, AtlasAtlas GovernmentGovernment ProgramsPrograms BusinessBusiness DevelDevelopmentopment andand AdvancedAdvanced ProgramsPrograms 33 AugustAugust 20062006 1 Video – Take a Ride 2 ReliableReliable && VersatileVersatile LaunchLaunch VehicleVehicle FamilyFamily RReettiirreedd RReettiirreedd Atlas I AC-69 RReettiirreedd Jul 1990 Atlas II AC-102 RReettiirreedd 8/11 Dec 1991 Atlas IIA 10/10 AC-105 RReettiirreedd Jun 1992 • Consecutive Successful Atlas CentaurAtlas Flights: IIAS 79 Retired • First Flight Successes: 823/23 of 8 AC-108 Retired • Mission Success: 100% Atlas II, IIA, IIAS,Dec 1993 IIIA, IIIB, and V Families Atlas IIIA First Flight • Retired Variants: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H,30/30 I, II, IIA, IIAS,AC-201 IIIA, IIIB May 2000 Atlas IIIB X/Y AC-204 2/2 X Successes / Y FlightsFeb 2002 Atlas V-400 AV-001 4/4 Mission Success: One Launch at a Time 4/4 Aug 2002 Atlas V-500 AV-003 4/4 Jul 2003 3/3 3 RecentRecent AtlasAtlas // CentaurCentaur EvolutionEvolution Atlas I / II Family Atlas III Family Atlas V Family dd dd iirree iirree eett eett RR RR 5-m PLF 30 GSO Kit 26 Single Avionics Engine Common Upgrade 22 Centaur Centaur 3.8-m 18 Common LO2 Core Tank Booster Stretch 14 10 Liquid SRBs Strap-ons RD-180 SRBs 6 Engine Atlas I Atlas IIAS Atlas IIIA Atlas IIIB Atlas V Atlas V Atlas V 407 -

State of the Space Industrial Base 2020 Report

STATE OF THE SPACE INDUSTRIAL BASE 2020 A Time for Action to Sustain US Economic & Military Leadership in Space Summary Report by: Brigadier General Steven J. Butow, Defense Innovation Unit Dr. Thomas Cooley, Air Force Research Laboratory Colonel Eric Felt, Air Force Research Laboratory Dr. Joel B. Mozer, United States Space Force July 2020 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this report reflect those of the workshop attendees, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the US government, the Department of Defense, the US Air Force, or the US Space Force. Use of NASA photos in this report does not state or imply the endorsement by NASA or by any NASA employee of a commercial product, service, or activity. USSF-DIU-AFRL | July 2020 i ABOUT THE AUTHORS Brigadier General Steven J. Butow, USAF Colonel Eric Felt, USAF Brig. Gen. Butow is the Director of the Space Portfolio at Col. Felt is the Director of the Air Force Research the Defense Innovation Unit. Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate. Dr. Thomas Cooley Dr. Joel B. Mozer Dr. Cooley is the Chief Scientist of the Air Force Research Dr. Mozer is the Chief Scientist at the US Space Force. Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS FROM THE EDITORS Dr. David A. Hardy & Peter Garretson The authors wish to express their deep gratitude and appreciation to New Space New Mexico for hosting the State of the Space Industrial Base 2020 Virtual Solutions Workshop; and to all the attendees, especially those from the commercial space sector, who spent valuable time under COVID-19 shelter-in-place restrictions contributing their observations and insights to each of the six working groups. -

Atlas 5 Data Sheet

2/12/2018 Atlas 5 Data Sheet Space Launch Report: Atlas 5 Data Sheet Home On the Pad Space Logs Library Links Atlas 5 Vehicle Configurations Vehicle Components Atlas 5 Launch Record Atlas 5 was Lockheed Martin's Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) design for the U.S. Air Force. The United Launch Alliance consortium, a new company spun off by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, took over the Delta IV and Atlas V EELV programs in December 2006. The rocket, available in several variants, is built around a LOX/RP1 Common Core Booster (CCB) first stage and a LOX/LH2 Centaur second stage powered by one or two RL10 engines. Up to five solid rocket boosters (SRBs) can augment first stage thrust. A threedigit designator identifies Atlas V configurations. The first digit signifies the vehicle's payload fairing diameter in meters. The second digit tells the number of SRBs. The third digit provides the number of Centaur second stage RL10 engines (1 or 2). The Atlas V 400 series, with a 4 meter payload fairing and up to three SRBs, can boost up to 7.7 metric tons to a 28.7 deg geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO) or 15.26 tonnes to a 28.7 deg low earth orbit (LEO) from Cape Canaveral. Atlas V 500, with a 5 meter diameter payload fairing and up to five SRBs, can put up to 8.9 tonnes to a 28.7 deg GTO or 18.85 tonnes into a 28.7 deg LEO. A 2.5 stage, Atlas 5 Heavy that uses three parallel burn CCBs, has been designed but not developed. -

2013 Commercial Space Transportation Forecasts

Federal Aviation Administration 2013 Commercial Space Transportation Forecasts May 2013 FAA Commercial Space Transportation (AST) and the Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC) • i • 2013 Commercial Space Transportation Forecasts About the FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation The Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA AST) licenses and regulates U.S. commercial space launch and reentry activity, as well as the operation of non-federal launch and reentry sites, as authorized by Executive Order 12465 and Title 51 United States Code, Subtitle V, Chapter 509 (formerly the Commercial Space Launch Act). FAA AST’s mission is to ensure public health and safety and the safety of property while protecting the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States during commercial launch and reentry operations. In addition, FAA AST is directed to encourage, facilitate, and promote commercial space launches and reentries. Additional information concerning commercial space transportation can be found on FAA AST’s website: http://www.faa.gov/go/ast Cover: The Orbital Sciences Corporation’s Antares rocket is seen as it launches from Pad-0A of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport at the NASA Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, Sunday, April 21, 2013. Image Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls NOTICE Use of trade names or names of manufacturers in this document does not constitute an official endorsement of such products or manufacturers, either expressed or implied, by the Federal Aviation Administration. • i • Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 1 COMSTAC 2013 COMMERCIAL GEOSYNCHRONOUS ORBIT LAUNCH DEMAND FORECAST . -

Space Is Open for Business

Rocket Lab USA SPACE IS OPEN FOR BUSINESS Investor Presentation March 2021 rocketlabusa.com DISCLAIMER AND FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS This presentation (this “Presentation”) was based on Vector’s and Rocket Lab’s current are not undertaking any obligation to update and unanticipated events may occur that non-GAAP measures to compare Rocket statement, the proxy statement/prospectus prepared for informational purposes only expectations and beliefs concerning future or revise any forward-looking statements could affect results. Therefore, actual results Lab’s performance to that of prior periods and all other relevant documents filed or that to assist interested parties in making their developments and their potential effects on whether as a result of new information, future achieved during the periods covered by the for trend analyses and for budgeting and will be filed with the SEC by Rocket Lab and own evaluation of the proposed transaction Vector, Rocket Lab or any successor entity events or otherwise. projections may vary and may vary materially planning purposes. Not all of the information Vector through the website maintained by (the “Transaction”) between Vector of the Transaction. Many factors could cause All rights to the trademarks, copyrights, from the projected results. Inclusion of the necessary for a quantitative reconciliation the SEC at www.sec.gov. Acquisition Corporation Inc. (“Vector”, “we”, actual future events to differ materially logos and other intellectual property listed prospective financial information in this of these forward-looking non-GAAP The documents filed by Vector with the or “our”) and Rocket Lab USA, Inc. (“Rocket from the forward-looking statements in herein belong to their respective owners and presentation should not be regarded as financial measures to the most directly SEC also may be obtained free of charge Lab”). -

Technical Report on Different RLV Return Modes' Performances

Formation flight for in-Air Launcher 1st stage Capturing demonstration Technical Report on different RLV return modes’ Performances Deliverable D2.1 EC project number 821953 Research and Innovation action Space Research Topic: SPACE-16-TEC-2018 – Access to space FALCon Formation flight for in-Air Launcher 1st stage Capturing demonstration Technical Report on different RLV return modes’ Performances Deliverable Reference Number: D2.1 Due date of deliverable: 30th November 2019 Actual submission date (draft): 15th December 2019 Actual submission date (final version): 19th October 2020 Start date of FALCon project: 1st of March 2019 Duration: 36 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: DLR Revision #: 2 Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) APPROVAL Title issue revision Technical Report on different RLV return modes’ 2 1 performances Author(s) date Sven Stappert 19.10.2020 Madalin Simioana 21.07.2020 Martin Sippel Approved by Date Sven Stappert 19.10.2020 Martin Sippel FALCon D2.1: RLV Return Mode Performances vers. 19-Oct-20 Page i Contents List of Tables iii List of Figures iii Nomenclature vi 1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Scope of the deliverable ............................................................................................ -

Quarterly Launch Report

Commercial Space Transportation QUARTERLY LAUNCH REPORT Featuring the launch results from the previous quarter and forecasts for the next two quarters. 1st Quarter 1996 United States Department of Transportation • Federal Aviation Administration Office of Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation Quarterly Launch Report 1 1st QUARTER REPORT Objectives This report summarizes recent and scheduled worldwide commercial, civil, and military orbital space launch events. Scheduled launches listed in this report are vehicle/payload combinations that have been identified in open sources including industry references, company manifests, periodicals, and government documents. Note that such dates are subject to change. The report highlights commercial launch activities, classifying commercial launches as one or more of the following: • internationally competed launch events (i.e. launch opportunities considered available in principle to competitors in the international launch services market), • any launches licensed by the Office of the Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation of the Federal Aviation Administration under U.S. Code Title 49, Subsection 9, Section 701 (previously known as the Commercial Space Launch Act), and • certain European launches of Post, Telegraph and Telecommunications payloads on Ariane vehicles. Photo credit: Lockheed Martin Corporation (1995). Image is of the Atlas 2A launch on December 15, 1995. It successfully orbited a Galaxy 3R commercial communications satellite for Hughes Communications,