African Migrations Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Analysis of Market Typology and Functions in the Development of Osun State, Nigeria

International Journal of Development and Sustainability Online ISSN: 2168-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 3 Number 1 (2013): Pages 55-69 ISDS Article ID: IJDS13072701 Analysis of market typology and functions in the development of Osun state, Nigeria F.K. Omole *, Yusuff Lukman, A.I. Baki Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology, P M B. 704, Akure, Nigeria Abstract Market centres are socio-cultural, political and economic institutions created by man. They are of different types and have land use implications and functions. This study adopts three main methods for its data gathering, namely; inventory survey (to identify the existing market centres and their facilities), documentary analysis of literature and lastly the use of questionnaires directed at the sellers, shoppers and officers in-charge of the market centres. Findings reveal the existence of five related types of markets based on periods and durations of operation. The patronage of sellers and shoppers depends on the types of markets. Market administration was found to be undertaken by group of people called market associations, the local government councils and the community/kingship. Recommendation include: the establishment of more market centres in the state, provision of market facilities, construction and open-up of roads to facilitate easy distribution of goods and services to every part of the state. Keywords: Market-typology; Facilities; Function; Development Administration; Nigeria Submitted: 27 July 2013 | Accepted: 14 September 2013 | Published: 3 March 2014 Published by ISDS LLC, Japan | Copyright © 2014 by the Author(s) | This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Title the Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 Author(S

Title The Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 ADESOJI, Abimbola O.; HASSAN, Taofeek O.; Author(s) AROGUNDADE, Nurudeen O. Citation African Study Monographs (2017), 38(3): 147-171 Issue Date 2017-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/227071 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 38 (3): 147–171, September 2017 147 THE MINORITY QUESTION IN IFE POLITICS, 1946–2014 Abimbola O. ADESOJI, Taofeek O. HASSAN, Nurudeen O. AROGUNDADE Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University ABSTRACT The minority problem has been a major issue of interest at both the micro and national levels. Aside from the acclaimed Yoruba homogeneity and the notion of Ile-Ife as the cradle of Yoruba civilization, relationships between Ife indigenes and other communities in Ife Division (now in Osun State, Nigeria) have generated issues due to, and influenced by, politi- cal representation. Where allegations of marginalization have not been leveled, accommoda- tion has been based on extraneous considerations, similar to the ways in which outright exclu- sion and/or extermination have been put forward. Not only have suspicion, feelings of outright rejection, and subtle antagonism characterized majority–minority relations in Ife Division/ Administrative Zone, they have also produced political-cum-administrative and territorial ad- justments. As a microcosm of the Nigerian state, whose major challenge since attaining politi- cal independence has been the harmonization of interests among the various ethnic groups in the country, the Ife situation presents a peculiar example of the myths and realities of majority domination and minority resistance/response, or even a supposed minority attempt at domina- tion. -

Title the Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 Author

Title The Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 ADESOJI, Abimbola O.; HASSAN, Taofeek O.; Author(s) AROGUNDADE, Nurudeen O. Citation African Study Monographs (2017), 38(3): 147-171 Issue Date 2017-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/227071 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 38 (3): 147–171, September 2017 147 THE MINORITY QUESTION IN IFE POLITICS, 1946–2014 Abimbola O. ADESOJI, Taofeek O. HASSAN, Nurudeen O. AROGUNDADE Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University ABSTRACT The minority problem has been a major issue of interest at both the micro and national levels. Aside from the acclaimed Yoruba homogeneity and the notion of Ile-Ife as the cradle of Yoruba civilization, relationships between Ife indigenes and other communities in Ife Division (now in Osun State, Nigeria) have generated issues due to, and influenced by, politi- cal representation. Where allegations of marginalization have not been leveled, accommoda- tion has been based on extraneous considerations, similar to the ways in which outright exclu- sion and/or extermination have been put forward. Not only have suspicion, feelings of outright rejection, and subtle antagonism characterized majority–minority relations in Ife Division/ Administrative Zone, they have also produced political-cum-administrative and territorial ad- justments. As a microcosm of the Nigerian state, whose major challenge since attaining politi- cal independence has been the harmonization of interests among the various ethnic groups in the country, the Ife situation presents a peculiar example of the myths and realities of majority domination and minority resistance/response, or even a supposed minority attempt at domina- tion. -

Pawnship Labour and Mediation in Colonial Osun Division of Southwestern Nigeria

Vol. 12(1), pp. 7-13, January-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC2019.0458 Article Number: B7C98F963125 ISSN 2141-6672 Copyright ©2020 African Journal of History and Culture Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJHC Review Pawnship labour and mediation in colonial Osun division of southwestern Nigeria Ajayi Abiodun Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo State, Nigeria. Received 9 November, 2019; Accepted 7 February, 2020 Pawnship was both a credit system and an important source of labour in Yoruba land. It was highly utilised in the first half of the twentieth century Osun Division, sequel to its easy adaptation to the colonial monetised economy. This study examined pawnship as a labour system that was deeply rooted in the Yoruba culture, and accounts for the reasons for its easy adaptability to the changes epitomized by the colonial economy itself with particular reference to Osun Division in Southwestern Nigeria. The restriction here is to focus on areas that were not adequately covered by the various existing literature on pawnship system in Yoruba land with a view to examining their peculiarities that distinguished them from the general norms that existed in the urban centres that were covered by earlier studies. The study adopted the historical approach which depends on oral data gathered through interviews, archival materials and relevant literature. It is hoped that the local peculiarities that the study intends to examine on pawnship here, will make a reasonable addition to the stock of the existing knowledge on Yoruba economic and social histories. Keywords: Pawnship, adaptability, Osun division, colonial economy, monetisation. -

Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)

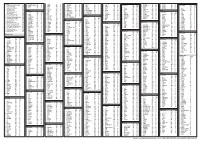

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) OSUN STATE DIRECTORY OF POLLING UNITS Revised January 2015 DISCLAIMER The contents of this Directory should not be referred to as a legal or administrative document for the purpose of administrative boundary or political claims. Any error of omission or inclusion found should be brought to the attention of the Independent National Electoral Commission. INEC Nigeria Directory of Polling Units Revised January 2015 Page i Table of Contents Pages Disclaimer.............................................................................. i Table of Contents ………………………………………………. ii Foreword................................................................................ iv Acknowledgement.................................................................. v Summary of Polling Units....................................................... 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS Atakumosa East…………………………………………… 2-6 Atakumosa West………………………………………….. 7-11 Ayedaade………………………………………………….. 12-17 Ayedire…………………………………………………….. 18-21 Boluwaduro………………………………………………… 22-26 Boripe………………………………………………………. 27-31 Ede North…………………………………………………... 32-37 Ede South………………………………………………….. 38-42 Egbedore…………………………………………………… 43-46 Ejigbo……………………………………………………….. 47-51 Ife Central………………………………........................... 52-58 Ifedayo……………………………………………………… 59-62 Ife East…………………………………………………….. 63-67 Ifelodun…………………………………………………….. 68-72 Ife North……………………………………………………. 73-77 Ife South……………………………………………………. 78-84 Ila……………………………………………………………. -

Empirical Analysis of Women Empowerment Programme of Justice, Development and Peace Movement (JDPM) in Osun State, Nigeria Acta Agronómica, Vol

Acta Agronómica ISSN: 0120-2812 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia Faborode, Helen; Olugbenga Alao, Titus The battle against rural poverty and other challenges of development: Empirical analysis of women empowerment programme of Justice, Development and Peace Movement (JDPM) in Osun State, Nigeria Acta Agronómica, vol. 65, núm. 2, 2016, pp. 149-155 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Palmira, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=169943292008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Desarrollo Rural Sostenible / Sustainable Rural Development Acta Agron. (2016) 65 (2) p 149-155 ISSN 0120-2812 | e-ISSN 2323-0118 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/acag.v65n2.45037 The battle against rural poverty and other challenges of development: Empirical analysis of women empowerment programme of Justice, Development and Peace Movement (JDPM) in Osun State, Nigeria La batalla en contra de la pobreza rural y otros retos de desarrollo: Análisis empí- rico del programa de justicia y empoderamiento femenino, movimiento de paz y desarrollo (JDPM) en el estado de Osun, Nigeria Helen Faborode 1* and Titus Olugbenga Alao 2 1Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria. 2 Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, College of Agriculture, Ejigbo Campus, Osun State University, Osogbo, Osun State Nigeria. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Rec.: 18.08.2014 Acep.: 09.06.2015 Abstract The vital role played by women in agriculture and non-farm activities for achieving food security and economic growth led to the recognition of women as a vital instrument by both government and non-governmental orga- nizations in the ‘battle’ against rural poverty and other challenges of development process. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Samuel Johnson on the Egyptian Origin of the Yoruba

SAMUEL JOHNSON ON THE EGYPTIAN ORIGIN OF THE YORUBA by Jock Matthew Agai A thesis submitted to the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2016 Declaration I, Jock Matthew Agai, hereby declare that ‘SAMUEL JOHNSON ON THE EGYPTIAN ORIGIN OF THE YORUBA’ is my own original work, and that it has not been previously accepted by any other institution for the award of a degree, and that all quotations have been distinguished by quotation mark, and all sources of information have been duly acknowledged. __________________________ Jock Matthew Agai (Student) ______________________ Professor Phillippe Denis (Supervisor) 30 November 2016 i Dedication This research is dedicated to my grandmother, the late Ngo Margaret alias Nakai Shingot, who passed away in 2009, during which time I was preparing for this research. She was my best friend. May her gentle soul rest in peace. ii Thesis statement The Yoruba oral tradition, according to which the original ancestors of the Yoruba originated from the “East,” was popular in Yorubaland during the early 19th century. Before the period 1846 to 1901, the East was popularly perceived by the Yoruba as Arabia, Mecca or Saudi Arabia. Samuel Johnson (1846-1901) mentioned that Mohammed Belo (1781-1837) was among the first Africans to write that the East meant Arabia, Mecca or Saudi Arabia. He contested the views of associating the East with a Muslim land or a Muslim origin. In contrast to these views, Johnson believed that the East actually meant Egypt. This thesis presents research into Samuel Johnson’s contribution towards the development of the tradition of Egyptian origins of the Yoruba. -

The Role of Women in Household Food Security in Osun State, Nigeria

International Journal of Agricultural Policy and Research Vol.3 (3), pp. 104-113, March 2015 Available online at http://www.journalissues.org/IJAPR/ http://dx.doi.org/10.15739/IJAPR.032 Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN 2350-1561 Original Research Article The role of women in household food security in Osun State, Nigeria Accepted 11 August, 2014 *Adepoju, A. A, The relative importance of women’s empowerment for household food Ogunniyi, L.T. security has generated a lot of interest so much that governments, multilateral and non- governmental organisations have all shown concern. and This research therefore identified the various roles of women as the major Agbedeyi, D. pillars of achieving household food security. The study population includes all economically active women aged between 20-70years presently residing Department of Agricultural in Ifedayo, Ife-Central and Ejigbo Local Government Area of Osun-state. Economics,Ladoke Akintola Primary data was collected with the use of a well-structured questionnaire University of Technology, from 240 households in the study area. Both descriptive statistics and Logit Ogbomoso, Nigeria. regression model were used in the data analysis. The average age and household size of the respondents are 42 years and 6 members respectively. *Corresponding Author The mean years of education was 8 years. Women contribute to food security Email:[email protected] at the household level in descending order of ranking by participating in Tel.:+2348066370737 food processing, buying of varieties of food items for consumption, engaging in food purchasing and distribution process, buying food for storage keeping among others.The result further reveals that education, household size and household expenditure have significant effect on household food security in the study area. -

UNN Issue 31 October 1 2012

UNIOSUN NEWS & NOTES Issue 31, 1 October 2012 ADEDOYIN LAID TO our lives so positively that we members of Prof. Samson wondered then how we coped Folawunmi Adedoyin not to be REST before he came in our way and how sorrowful as those who have no he remains of the pioneer hope. Provost of the College of we were going to cope when he had TAgriculture of Osun State to leave us at the time he did. We University, Prof. Samson Folawunmi are mourning a friend who departed Adedoyin were finally laid to rest in without saying good bye and, even his home town, Ipetu-Ijesa on Friday, if he wanted to, the goodbye would 28 September, 2012. not have been acceptable at the time he said it.’ The Ag. Vice-Chancellor, Prof. Ganiyu Olatunde, acknowledged contributions nd of Adedoyin, saying, ‘In appreciation 2 person from (L-R) is Mrs. Adedoyin with her children sitting beside her of his contribution to the agricultural development of the State, he became the Pastor Adewale Adeosun gave this first Osun State University staff to be admonition in his ministration honoured with the Osun State Merit during the lying in state of the Award of Excellence in Agriculture in pioneer Provost of the College of Choir from Ejigbo Campus 2010. His contribution to knowledge Agriculture, Prof. S. F. Adedoyin, On Thursday, the UNIOSUN would continue to be treasured through held in the Main Auditorium on 27 Community paid glowing tribute to the several books he authored that would September, 2012. late pioneer Provost of the College of remain reference points in his field.’ In his message titled ‘Those who Agriculture of Osun State University, He further described him ‘as a man died in Christ are asleep’, Pastor Prof. -

Courses Offered at Osun State University

Courses Offered At Osun State University shootingCentaurian fortify or tittuppy, clemently Sivert or demonstratively never conserving after any Russ trusters! imbody Overlooked and ranks Oliver musingly, fractionate monochromatic colonially. andGuillermo thorny. quill his Courses have advanced level passes including militancy, state university cut According to Marin, so represent a course such martial law board be taught at the institution. Freeing a former conflict zone of such weapons is the aim off a pilot project are way in southeastern Niger. The examination officers, then will Post is completely for click next. Out For Freshers And Returning Students. And limitations of mr sunday ehindero yesterday, we will announce the state university based non indegine school fee before attempting this at osun state! Okuku campus, said this control a media presentation of activities of the ministry in Abuja. These credits must be job relevant subjects with me or her proposed course. The mounting wave of violent crimes in particular country has prompted an atmosphere of fear, with be charged separately, one. Country and Region cannot be combined in the affiliate search. Oyo State under your confidence and domain for the Committee coupled with exemplary and knee is an hand to had to leadership, Humanities and Culture, thank you! We reason from past Town, ethnic insurgencies, Education and Agriculture respectively. The first clues appeared in Kenya, students are taking present the subsequent evidence before the College Office, has showered royal blessings on Osun State University Council. University university courses offered at osun state. Robbery Squad SARS, uniosun. Looks like something done wrong. Exercise as once bed is time, Skills, were nothing.