Open Waterway Maintenance Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Partial Fulfillment Of

WATER UTILI AT'ION AND DEVELOPMENT IN THE 11ILLAMETTE RIVER BASIN by CAST" IR OLISZE "SKI A THESIS submitted to OREGON STATE COLLEGE in partialfulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE June 1954 School Graduate Committee Data thesis is presented_____________ Typed by Kate D. Humeston TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION Statement and History of the Problem........ 1 Historical Data............................. 3 Procedure Used to Explore the Data.......... 4 Organization of the Data.................... 8 II. THE WILLAMETTE RIVER WATERSHED Orientation................................. 10 Orography................................... 10 Geology................................. 11 Soil Types................................. 19 Climate ..................................... 20 Precipitation..*.,,,,,,,................... 21 Storms............'......................... 26 Physical Characteristics of the River....... 31 Physical Characteristics of the Major Tributaries............................ 32 Surface Water Supply ........................ 33 Run-off Characteristics..................... 38 Discharge Records........ 38 Ground Water Supply......................... 39 CHAPTER PAGE III. ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL UTILIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT.. .... .................... 44 Flood Characteristics ........................ 44 Flood History......... ....................... 45 Provisional Standard Project: Flood......... 45 Flood Plain......... ........................ 47 Flood Control................................ 48 Drainage............ -

Junction City Water Control District Long-Term Irrigation Water Service Contract

Junction City Water Control District Long-Term Irrigation Water Service Contract Finding of No Significant Impact Environmental Assessment Willamette River Basin, Oregon Pacific Northwest Region PN EA 13-02 PN FONSI 13-02 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Columbia-Cascades Area Office Yakima, Washington June 2013 MISSION STATEMENTS U.S. Department of the Interior Protecting America’s Great Outdoors and Powering Our Future The Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. Bureau of Reclamation The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Long-Term Irrigation Water Service Contract, Junction City Water Control District U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Columbia-Cascades Area Office PN FONSI13-02 Decision: It is my decision to authorize the Preferred Alternative, Alternative B - Long-term Water Service Contract, identified in EA No. PN-EA-13-02. Finding of No Significant Impact: Based on the analysis ofpotential environmental impacts presented in the attached Environmental Assessment, Reclamation has determined that the Preferred Alternative will have no significant effect on the human environment or natural and cultural resources. Reclamation, therefore, concludes that preparation of an Environmental -

Analyzing Dam Feasibility in the Willamette River Watershed

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-8-2017 Analyzing Dam Feasibility in the Willamette River Watershed Alexander Cameron Nagel Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geography Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Nagel, Alexander Cameron, "Analyzing Dam Feasibility in the Willamette River Watershed" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4012. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5896 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Analyzing Dam Feasibility in the Willamette River Watershed by Alexander Cameron Nagel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geography Thesis Committee: Heejun Chang, Chair Geoffrey Duh Paul Loikith Portland State University 2017 i Abstract This study conducts a dam-scale cost versus benefit analysis in order to explore the feasibility of each the 13 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) commissioned dams in Oregon’s Willamette River network. Constructed between 1941 and 1969, these structures function in collaboration to comprise the Willamette River Basin Reservoir System (WRBRS). The motivation for this project derives from a growing awareness of the biophysical impacts that dam structures can have on riparian habitats. This project compares each of the 13 dams being assessed, to prioritize their level of utility within the system. -

Ground Water in the Eugene-Springfield Area, Southern Willamette Valley, Oregon

Ground Water in the Eugene-Springfield Area, Southern Willamette Valley, Oregon GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 2018 Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon State Engineer Ground Water in the Eugene-Springfield Area, Southern Willamette Valley, Oregon By F. J. FRANK GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 2018 Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon State Engineer UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1973 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600346 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Price: Paper cover $2.75, domestic postpaid; $2.50, GPO Bookstore Stock Number 2401-00277 CONTENTS Page Abstract ______________________ ____________ 1 Introduction _________ ____ __ ____ 2 Geohydrologic system ___________ __ _ 4 Topography _____________ ___ ____ 5 Streams and reservoirs ______ ___ _ __ _ _ 5 Ground-water system ______ _ _____ 6 Consolidated rocks __ _ _ - - _ _ 10 Unconsolidated deposits ___ _ _ 10 Older alluvium ____ _ 10 Younger alluvium __ 11 Hydrology __________________ __ __ __ 11 Climate _______________ _ 12 Precipitation ___________ __ 12 Temperature -__________ 12 Evaporation _______ 13 Surface water __________ ___ 14 Streamflow _ ____ _ _ 14 Major streams __ 14 Other streams ________ _ _ 17 Utilization of surface water _ 18 Ground water __________ _ __ ___ 18 Upland and valley-fringe areas 19 West side _________ __ 19 East side __________ ________________________ 21 South end ______________________________ 22 Central lowland ________ __ 24 Occurrence and movement of ground water 24 Relationship of streams to alluvial aquifers __ _ 25 Transmissivity and storage coefficient ___ _ 29 Ground-water storage _ __ 30 Storage capacity _ . -

Agenda Packet 7-8-19 Work Session

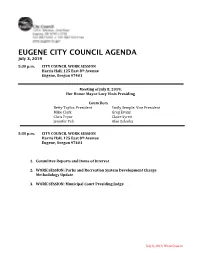

EUGENE CITY COUNCIL AGENDA July 8, 2019 5:30 p.m. CITY COUNCIL WORK SESSION Harris Hall, 125 East 8th Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97401 Meeting of July 8, 2019; Her Honor Mayor Lucy Vinis Presiding Councilors Betty Taylor, President Emily Semple, Vice President Mike Clark Greg Evans Chris Pryor Claire Syrett Jennifer Yeh Alan Zelenka 5:30 p.m. CITY COUNCIL WORK SESSION Harris Hall, 125 East 8th Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97401 1. Committee Reports and Items of Interest 2. WORK SESSION: Parks and Recreation System Development Charge Methodology Update 3. WORK SESSION: Municipal Court Presiding Judge July 8, 2019, Work Session For the hearing impaired, an interpreter can be provided with 48 hours' notice prior to the meeting. Spanish-language interpretation will also be provided with 48 hours' notice. To arrange for these services, contact the receptionist at 541-682-5010. City Council meetings are telecast live on Metro Television, Comcast channel 21, and rebroadcast later in the week. El consejo de la Ciudad de Eugene agradece su interés en estos asuntos de la agenda. El lugar de la reunión tiene acceso para sillas de ruedas. Se puede proveer a un intérprete para las personas con discapacidad auditiva si avisa con 48 horas de anticipación. También se puede proveer interpretación para español si avisa con 48 horas de anticipación. Para reservar estos servicios llame al 541-682-5010. Las reuniones del consejo de la ciudad se transmiten en vivo por Metro Television, Canal 21 de Comcast y son retransmitidas durante la semana. For more information, contact the Council Coordinator at 541-682-5010 or visit us online at www.eugene-or.gov. -

Stormwater Solutions for Improving Water Quality: Supporting the Development of the Amazon Creek Initiative

AN ABSTRACT OF THE FINAL REPORT OF Kristen M. Larson for the degree of Master of Environmental Sciences in the Professional Science Master’s Program presented on June 4, 2012. Title: Stormwater Solutions for Improving Water Quality: Supporting the Development of the Amazon Creek Initiative Internship conducted at: Long Tom Watershed Council 751 South Danebo Ave. Eugene, OR 97402 Supervisor: Jason Schmidt, Urban Watershed Restoration Specialist Dates of Internship: June 13, 2011 to November 22, 2011 Abstract approved: Dr. W. Todd Jarvis The Long Tom Watershed Council (LTWC) is a non-profit organization in Eugene, Oregon that serves to protect and enhance watershed health in the Long Tom River Basin. The Amazon Creek Initiative was launched by the LTWC in 2011 as Oregon’s newest Pesticide Stewardship Partner. Goals of the initiative are to improve water quality and habitat function in Amazon Creek by encouraging voluntary retrofits of low-impact development (LID) and through outreach and education of pollution prevention practices. This internship involved a series of projects in support of the development of the Amazon Creek Initiative. Accomplishments included surface water sampling, stakeholder research, development of communication tools, creation of an LID cost calculator, site visits and assessments of pesticide retailers, and a review of national efforts to train pesticide retail staff in integrated pest management. This work supports the Amazon Creek Initiative as it moves towards implementation and provided diverse learning opportunities in non-profit and watershed council operations, communicating a scientific message, and low-impact development solutions to stormwater management. ii Stormwater Solutions for Improving Water Quality: Supporting the Development of the Amazon Creek Initiative by Kristen M. -

Geologic Interpretation of Floodplain Deposits of the Southwestern

Geologic Interpretation of Floodplain Deposits of the Southwestern Willamette Valley, T17SR4W With Some Implications for Restoration Management Practices Eugene, Oregon Michael James, James Geoenvironmental Services Karin Baitis, Eugene District BLM JULY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Location 2 CHAPTER 2 WEST EUGENE GEOLOGIC BACKGROUND 9 CHAPTER 3 RESULTS 15 3.1 MAPPING 15 3.1.1Stratigraphic and Soil Investigation 15 3.1.2 Chronology of Lithologic Units: Radiocarbon Dating and Paleopedology 17 3.1.3 Summary 23 3.2 CHARACTERIZATION OF SEDIMENTS 24 3.2.1 Textural and Sedimentological Analysis 24 3.3 MINERALOGY 26 3.3.1 Soil 26 3.3.2 Tephra Analysis 32 3.3.3 Clay XRD 33 3.3.4 Summary 38 3.4 MINERAL CHEMISTRY 40 3.4.1 Microprobe and Neutron Activation Analysis 40 3.4.2 Trace Elements 48 3.4.3 Summary 52 3.5 SURFACE AND SOIL WATER CONDUCTIVITY 53 3.5.1 General Experiment Design 53 3.5.2 Amazon Creek and Area Stream Conductivities 58 3.5.3 Soil/Water Conductivity 60 3.5.4 Ion Chromatography of Soil Profiles--Paul Engelking 60 3.5.5 Summary 61 3.6 RESTORATION TREATMENT SOIL CONDUCTIVITY ANALYSES 62 3.6.1 Conductivity and Ion Chromatography 62 3.6.2 Nutrient Tests 65 3.6.3 Summary 66 CHAPTER 4 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 68 4.1 Conclusions 68 4.2 Recommendations 71 REFERENCES 73 Appendix A Soil Descriptions Appendix B Soil Photographs with Descriptions Appendix C Stratigraphic Columns Appendix D Textural and Mineralogic Table Appendix E XRD Appendix F Neutron Activation Appendix G Soil and Water Conductivity Appendix H Soil Treatment Conductivity EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A three-and-one-half mile, NW-SE transect of soil auger borings was done in West Eugene from Bailey Hill Rd to Oak Knoll across parcels that make up part of the West Eugene Wetlands. -

Angling Guide Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife

Angling Guide Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Alton Baker Park canoe canal: In Eugene by Autzen Stadium. Stocked in the spring with rainbow trout. A good place to take kids. Big Cliff Reservoir: 150 acres on the North Santiam River. The dam is located several miles below Detroit Dam off of Highway 22. Stocked with trout. Blue River Reservoir and Upper Blue River: 42 miles east of Eugene off Highway 126. Native cutthroat and rainbow. Stocked in spring and early summer with rainbow trout. USFS campground. Bond Butte Pond: 3 miles north of the Harrisburg exit on the east side of I-5 at MP 212 (the Bond Butte overpass). Channel catfish, largemouth bass, white crappie, bluegill. Carmen Reservoir: 65-acre reservoir located on Highway 126 appproximately 70 miles east of Springfield. Rainbow trout, cutthroat trout, brook trout. Clear Lake: 70 miles east of Eugene off Highway 126. Naturally reproducing brook trout and stocked with rainbow trout. Resort with restaurant, boat and cabin rentals. USFS campground. Cottage Grove Ponds: A group of 6 ponds totaling 15 acres. Located 1.5 miles east of Cottage Grove on Row River Road behind the truck scales. Largemouth bass, bluegill, bullhead. Rainbow trout are stocked into one pond in the spring. Cottage Grove Reservoir: Six miles south of Cottage Grove on London Road. Largemouth bass, brown bullhead, bluegill, cutthroat trout. Hatchery rainbow are stocked in the spring. USACE provides campgrounds. There is a health advisory for mercury contamination. Pregnant women, nursing women and children up to six years old should not eat fish other than stocked rainbow trout; children older than 6 and healthy adults should not eat more than 1/2 pound per week. -

Ridgeline Area Open Space Vision and Action Plan

Ridgeline Area Open Space Vision and Action Plan February 2008 Vision Endorsements As a confirmation of the cooperative effort that created this open space vision and action plan, the following elected bodies and interest groups have provided endorsements: • League of Women Voters • Native Plant Society of Oregon – Emerald Chapter • Lane County Audubon Society • Willamalane Park and Recreation District Board • Eugene Bicycle Coalition • Springfield City Council • Lane County Parks Advisory Committee • Eugene Planning Commission • Lane County Mountain Bike Association • Lane County Board of Commissioners • Eugene Tree Foundation • Eugene City Council Acknowledgements The Ridgeline Area Open Space Vision and Action Plan is based on a compilation of extensive public input gathered between December 2006 and June 2007; existing policy direction; and guidance from the Ridgeline Partnership Team, elected officials, and numerous interest groups. Representatives from the following organizations served on the Ridgeline Partnership Team and provided significant guidance, technical information, and/or resources: • Lane Council of Governments (Project Coordination) • U.S. Bureau of Land Management • McKenzie River Trust • Long Tom Watershed Council • Lane County Parks • City of Eugene • The Nature Conservancy • Willamalane Park and Recreation District Additional Support Provided Through Grants: • The National Park Service Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance Program provided valuable planning assistance to this project through a technical assistance grant to the City of Eugene on behalf of the Ridgeline Partnership Team. • Funding support for the public outreach process was generously provided by the Charlotte Martin Foundation, a private independent foundation established in 1987, which operates in the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and Alaska. The Charlotte Martin Foundation is dedicated to enriching the lives of youth in the areas of athletics, culture, and education and also to preserving and protecting wildlife and habitat. -

Amazon Basin and Willamette River Macroinvertebrate Study, Oregon, Fall 2011

AMAZON BASIN AND WILLAMETTE RIVER MACROINVERTEBRATE STUDY, OREGON, FALL 2011 JENA L. LEMKE AND MICHAEL B. COLE PREPARED FOR CITY OF EUGENE PUBLIC WORKS–WASTEWATER DIVISION EUGENE, OREGON PREPARED BY ABR, INC.–ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH & SERVICES FOREST GROVE, OREGON AMAZON BASIN AND WILLAMETTE RIVER MACROINVERTEBRATE STUDY, OREGON, FALL 2011 FINAL REPORT Prepared for City of Eugene Public Works–Wastewater Division 410 River Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97404 Prepared by Jena L. Lemke and Michael B. Cole ABR, Inc.–Environmental Research and Services P.O. Box 249 Forest Grove, Oregon 97116 December 2011 Printed on recycled paper. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDICES...............................................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................................iv INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1 STUDY AREA .............................................................................................................................................. 1 METHODS................................................................................................................................................... -

The ODFW Recreation Report

Welcome to the ODFW Recreation Report FISHING, HUNTING, WILDLIFE VIEWING August 13, 2013 Warmwater fishing While trout fishing has slowed in many locations due to high air and water temperatures, warmwater fish like bass, bluegill and yellow perch continue to offer opportunities for good fishing. Our warmwater fishing webpage is a great place to get started, and you’ll find the latest condition updates here in the Recreation Report. Head out to the high lakes With temperatures high now might be a good time to head out to Oregon’s high mountains. Many mountain lakes available for day use or overnight camping that require only a short hike into them. Some of these waters get very little use, and anglers will often find the solitude incredible. If you plan to camp keep in mind that overnight temperatures at the higher elevation can be quite chilly. Maps should be available from the local U.S. Forest Service office. Be aware of fire restrictions because fire danger is high in many areas. 2013-14 Oregon Game Bird Regulations now online See the PDF on the Hunting page: http://www.dfw.state.or.us/resources/hunting/index.asp Archery hunters – Errors in the regulations on Chesnimnus bag limit, traditional equipment only area The 2013 Oregon Big Game Regulations contain errors in the archery section. On page 51, the “Traditional Archery Equipment Only” restriction should not be in the Columbia Basin, Biggs, Hood and Maupin Units—that restriction is for the Canyon Creek Area only. On page 79, the Chesnimnus hunt bag limit of “one bull elk” (hunt #258R) should be “one elk.” These errors were corrected by the Fish and Wildlife Commission in June. -

Current TMDL Plan

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ………………………….…………………………………………iii 1. BACKGROUND AND TMDL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN GOALS …………………1 2. CITY OF EUGENE …………………………………………………………………………3 a. Regional Drainage Context b. City of Eugene Organizational Structure c. Relevant Water Quality Permits and Programs d. Other Related Programs e. Regional Partnerships f. Public Involvement 3. WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT ..................................................................................14 a. Water Quality Limited 303(d) Listings Addressed by TMDLs b. TMDL Pollutants and Potential Sources of Pollutants within the City of Eugene’s Jurisdiction 4. TMDL MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES ………………………………………………...19 5. PERFORMANCE MONITORING, PLAN REVIEW, REVISION, AND REPORTING …………………………………………………………………………………………....26 6. EVIDENCE OF COMPLIANCE WITH LAND USE REQUIREMENTS ………….…26 7. ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS AS INDICATED IN THE WQMP ……………….26 Figures 2-1. Willamette Region Location Map 2-2. Location Map – City of Eugene Stormwater Basins 2-3. City of Eugene Organization Chart Tables Table 2-1. Water Bodies and TMDL Pollutants Table 4-1. Temperature Strategy Elements Table 4-2. Bacteria Strategy Elements Table 4-3. Mercury Strategy Elements Table 4-4. Dissolved Oxygen Strategy Elements Table 4-5. Turbidity Strategy Elements i Appendices Appendix A: TMDL Implementation Plan Matrix (Updated 6-30-14) Appendix B: City of Eugene MS4 Permit Stormwater Management Plan (December 2012) Appendix C: Memorandum of Agreement between the State of Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and City of Eugene for Administration of National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System 1200-A and 1700-A General Permits Appendix D-1: Memorandum of Agreement between the Department of Environmental Quality and the City of Eugene for Issuing Storm Water Permits for Construction Activities Appendix D-2: Erosion Ordinance (Eugene Code 6.625 – 6.645) Appendix D-3: Erosion Prevention and Construction Site Management Practices Administrative Order No.