Immortal's Medicine: Daoist Healers and Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Usage of the Chinese Traditional “Yun Wen”

Research on Symbol Expression for Eye Image in Product Design: The Usage of the Chinese Traditional “Yun Wen” Chi-Chang Lu1 and Po-Hsien Lin2 1 Crafts and Design Department, National Taiwan University of Arts Ban Ciao City, Taipei 22058, Taiwan 2 Graduate School of Creative Industry Design, National Taiwan University of ArtsBan Ciao City, Taipei 22058, Taiwan {t0134,t0131}@ntua.edu.tw Abstract. In visual arts, using the eyes to deliver the message of life and emo- tion of a living thing has always been emphasized. The expression of the eyes is usually a combination of the eyeballs, pupils, eyelids, and eyelashes, etc. Among these, the pupil is of a crucial character. It completes the image of an eye and shows the direction of the line of sight. In this article, the authors wish to create a new way to show the symbols of eyes based on the Chinese tradi- tional cloud pattern- Yun Wen in the area of the product design. The design will combine the features of both the traditional cultural style and the vogue. It will also present the eastern aesthetics difference between visual similarity and visu- al dissimilarity. Keywords: Clouds pattern (Yun Wen), Chinese traditional pattern, decoration, eye image, cultural implication, product design. 1 Introduction At a product design event, the first author exhibited a teapot based on the form of the Chinese Prehistoric Pottery Gui-tripod. The Chinese traditional clouds pattern - Yun Wen- was selected for the symbolic decoration of a bird’s crest and wing to incorpo- rate extra traditional cultural elements into the design. -

Chinese Models for Chōgen's Pure Land Buddhist Network

Chinese Models for Chōgen’s Pure Land Buddhist Network Evan S. Ingram Chinese University of Hong Kong The medieval Japanese monk Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206), who so- journed at several prominent religious institutions in China during the Southern Song, used his knowledge of Chinese religious social or- ganizations to assist with the reconstruction of Tōdaiji 東大寺 after its destruction in the Gempei 源平 Civil War. Chōgen modeled the Buddhist societies at his bessho 別所 “satellite temples,” located on estates that raised funds and provided raw materials for the Tōdaiji reconstruction, upon the Pure Land societies that financed Tiantai天 台 temples in Ningbo 寧波 and Hangzhou 杭州. Both types of societ- ies formed as responses to catastrophes, encouraged diverse mem- berships of lay disciples and monastics, constituted geographical networks, and relied on a two-tiered structure. Also, Chōgen devel- oped Amidabutsu 阿弥陀仏 affiliation names similar in structure and function to those used by the “People of the Way” (daomin 道民) and other lay religious groups in southern China. These names created a collective identity for Chōgen’s devotees and established Chōgen’s place within a lineage of important Tōdaiji persons with the help of the Hishō 祕鈔, written by a Chōgen disciple. Chōgen’s use of religious social models from China were crucial for his fundraising and leader- ship of the managers, architects, sculptors, and workmen who helped rebuild Tōdaiji. Keywords: Chogen, Todaiji, Song Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, Pure Land society he medieval Japanese monk Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206) earned Trenown in his middle years as “the monk who traveled to China on three occasions,” sojourning at several of the most prominent religious institutions of the Southern Song (1127–1279), including Tiantaishan 天台山 and Ayuwangshan 阿育王山. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 11 2013 Contents In Memoriam ........................................................................................................................................................... [iii] Langdon Warner at Dunhuang: What Really Happened? by Justin M. Jacobs ............................................................................................................................ 1 Metallurgy and Technology of the Hunnic Gold Hoard from Nagyszéksós, by Alessandra Giumlia-Mair ......................................................................................................... 12 New Discoveries of Rock Art in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor and Pamir: A Preliminary Study, by John Mock .................................................................................................................................. 36 On the Interpretation of Certain Images on Deer Stones, by Sergei S. Miniaev ....................................................................................................................... 54 Tamgas, a Code of the Steppes. Identity Marks and Writing among the Ancient Iranians, by Niccolò Manassero .................................................................................................................... 60 Some Observations on Depictions of Early Turkic Costume, by Sergey A. Yatsenko .................................................................................................................... 70 The Relations between China and India -

The Nianfo in ºbaku Zen: a Look at the Teachings of the Three Founding Masters

James BASKIND * The Nianfo in ºbaku Zen: A Look at the Teachings of the Three Founding Masters To the Edo-period Japanese Zen monks, one of the most striking aspects of the ºbaku school was the practice of reciting the Buddha’s name (nianfo 念仏) within their teaching and training practices. For an accurate assessment of the ºbaku school’s true stance on the practice of the nianfo, however, it is necessary to investigate the writings and teachings of the school’s founding masters, the very figures who established and codified what came to be seen as standard practice: Yinyuan Longqi 隠元隆琦 (J. Ingen RyØki, 1592-1673), Muan Xingtao 木庵性瑫 (J. Mokuan ShØtØ, 1611-1684), and Jifei Ruyi 即非如一 (J. Sokuhi Nyoitsu, 1616-1671). It was the Japanese reaction to this practice that led to the accusation that the ºbaku monks were practicing an adulterated form of Zen that was contaminated by Pure Land elements. It remains, however, that much of the misunderstanding regarding nianfo practice can be assigned to the Japanese unfamiliarity with the doctrinal underpinnings of the Ming Buddhist models that the ºbaku monks brought to Japan. (Mohr 1994: 348, 364) This paper will attempt to clarify the nianfo teachings of these three foundational ºbaku masters. Chan and Pure Land Practices in China One thing that should be kept in mind when considering the Zen style of the ºbaku monks is that they were steeped in the Buddhist culture of the Ming period, replete with conspicuous Pure Land aspects. (Hirakubo 1962: 197) What appeared to the Japanese Zen community of the mid-seventeenth century as the incongruous marriage of Pure Land devotional elements within more traditional forms of Chan practice had already undergone a long courtship in China that had resulted in what seemed to the Chinese monks as a natural and legitimate union. -

Luxury Product Design for the Chinese Market

Luxury Product Design for the Chinese Market A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Design in the School of Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2012 By Gaoyan Shi MFA Zhejiang University of Technology, Zhejiang, P.R. China, 2009 Thesis Committee: Craig M. Vogel, Chair Peter A. Chamberlain Phyllis Borcherding Abstract China has become the world's largest consumer of luxury goods. The noticeable market performance has led to many luxury companies establishing their presence in China and setting expectations for strong growth. In such a competitive environment, the companies that can build their reputation and compete against others in the Chinese market will be those who clearly understand Chinese culture. Among the numerous factors that connect to the performance of business, design is playing an important part that cannot be ignored. However, although there are indeed much research of the Chinese luxury market, most of them are from the economic angle, seldom mention the design aspect. This project studies the design strategy of luxury products for Chinese market. It is based on the research on the current overall market situation of luxury product in China and application of Chinese culture in product design, in order to explore the appropriate design principles. One popular and effective way to attract Chinese consumers is to design culture- relative goods, nevertheless, because Chinese culture is complex and subtle, ii foreign companies inevitably have some misunderstandings and some of their corresponding designs become confusing and undesirable. -

Women Rulers in Imperial China

NAN N Ü Keith McMahonNan Nü 15-2/ Nan (2013) Nü 15 179-218(2013) 179-218 www.brill.com/nanu179 ISSN 1387-6805 (print version) ISSN 1568-5268 (online version) NANU Women Rulers in Imperial China Keith McMahon (University of Kansas) [email protected] Abstract “Women Rulers in Imperial China”is about the history and characteristics of rule by women in China from the Han dynasty to the Qing, especially focusing on the Tang dynasty ruler Wu Zetian (625-705) and the Song dynasty Empress Liu. The usual reason that allowed a woman to rule was the illness, incapacity, or death of her emperor-husband and the extreme youth of his son the successor. In such situations, the precedent was for a woman to govern temporarily as regent and, when the heir apparent became old enough, hand power to him. But many women ruled without being recognized as regent, and many did not hand power to the son once he was old enough, or even if they did, still continued to exert power. In the most extreme case, Wu Zetian declared herself emperor of her own dynasty. She was the climax of the long history of women rulers. Women after her avoided being compared to her but retained many of her methods of legitimization, such as the patronage of art and religion, the use of cosmic titles and vocabulary, and occasional gestures of impersonating a male emperor. When women ruled, it was an in-between time when notions and language about something that was not supposed to be nevertheless took shape and tested the limits of what could be made acceptable. -

Research on the Application of Chinese Traditional Pattern "Ruyi Pattern" in Buckle Design Jun Han1 Yangyang Jiang1,* Jun Li1

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 572 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021) Research on the Application of Chinese Traditional Pattern "Ruyi Pattern" in Buckle Design Jun Han1 Yangyang Jiang1,* Jun Li1 1 School of Art and Design, Wuhan Institute of Technology, Wuhan, Hubei 430205, China *Corresponding author. Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT Ruyi pattern is an important symbol of traditional Chinese auspicious patterns. With the development of the times, Ruyi pattern has flexibility and versatility in the process of application and has become an inexhaustible source of humanistic elements in contemporary art design. This article takes Ruyi pattern as the research object, starting from the meaning, origin, development history and types of Ruyi pattern, to understand and analyze, refine and simplify the modeling characteristics of traditional Ruyi pattern. By combining the specific design practice of Ruyi pattern in the buckle, the application of traditional Ruyi pattern in art design and its aesthetic value in real life can be made clear. Keywords: Ruyi pattern, Buckle design, Art design, Aesthetic value. 1. INTRODUCTION Therefore, the Ruyi patterns extracted from Ruyi also have beautiful meanings and symbols, and then Since the appearance of the Ruyi pattern, it has materialized into people's daily life, playing the role gone through the changes of the times. As one of of decoration and wishing on many utensils. the auspicious patterns, the Ruyi pattern is still popular today. The implied meaning of Ruyi 2.2 The Origin of Ruyi Pattern pattern is auspicious and wishful, which has rich emotional connotation; it has a variety of shapes, From the perspective of the development and beautiful and flexible lines, and it is beautiful, and evolution of Ruyi pattern’s modeling, it is itself it can be decorated with many kinds of utensils. -

Learning Resource Contents

Buddhism In e Chester Beatty Library A Learning Resource Contents Introduction 1 1 e ree Jewels of Buddhism 2 2 e Life of the Buddha 2 3 Samsara 3 4 eravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism 3 5 Buddhism in China 4-6 6 Buddhism in Japan 7-10 7 Buddhism in Tibet & Mongolia 11-13 8 Buddhism in South and South East Asia 14-18 9 Buddhist Symbols 19 Suggested Activities in the Chester Beatty Library 20 or in School Introduction The Buddhist collection in the Chester Beatty Library offers visitors the opportunity to explore the ‘Story of Buddhism’ from its origins with the life and teachings of the historical Buddha in India in the 6th century BC to its development as it spread through the countries of Asia. Students and educators are encouraged to explore a number of themes as presented in the exhibition on display in the Sacred Traditions Gallery. Aims Objectives • to support educators and students with a • to provide an understanding of symbolism in Buddhism comprehensive resource about Buddhism as reflected in • to provide the meanings of Buddhist art as found in the the Chester Beatty Library collections Chester Beatty Library collections • to lend to the Department of Education and Skill’s • to provide the opportunity for students and teachers to Intercultural Education Strategy 2010-2015 for schools, discuss and evaluate Buddhist art in the Chester Beatty with particular reference to cultural diversity in Irish Library collections schools 1 BUDDHISM IN THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY A LEARNING RESOURCE 1 e ree Jewels of Buddhism Key Words: The Three Jewels, The Buddha, the Dharma, the The Dharma Sangha, the Four Noble Truths, Nirvana, Siddhartha Gautama, The Buddha’s teachings are known as the Dharma. -

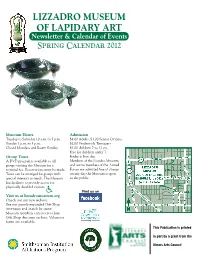

LIZZADRO MUSEUM of LAPIDARY ART Newsletter & Calendar Of

[email protected]. Russian jewelry. 45 minute video. minute 45 jewelry. Russian gemstones uniquely Scottish in design. in Scottish uniquely gemstones access for physically disabled visitors. disabled physically for access The Museum has facilities to provide provide to facilities has Museum The are located and see Tsar treasures and modern and treasures Tsar see and located are Please direct questions or comments to comments or questions direct Please etrsatqepee aeo ivrand silver of made pieces antique Features and palaces. Learn where major gem deposits deposits gem major where Learn palaces. and January 27 to May 10, 2009 10, May to 27 January We would like to hear from you. you. from hear to like would We Russia to explore the mineral wonders, museums, wonders, mineral the explore to Russia special interests or needs. or interests special Scottish Jewelry Scottish Exhibit Special Renowned lapidary writer, Bob Jones, travels to travels Jones, Bob writer, lapidary Renowned be made. Tours can be arranged for groups with with groups for arranged be can Tours made. be Visit us at www.lizzadromuseum.org at us Visit “Russian Gem Treasures” Gem “Russian the Museum for a nominal fee. Reservations must must Reservations fee. nominal a for Museum the Reservations Required: (630) 833-1616 (630) Required: Reservations A video program is available to all groups visiting visiting groups all to available is program video A Every Sunday Afternoon at 3 p.m. p.m. 3 at Afternoon Sunday Every Group Tours Group $30.00 per person, Museum Members $25.00 Members Museum person, per $30.00 Field Trip - 8 yrs.