A Module Compiled By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melissa Dejesus

Melissa DeJesus Mobile 646 344 2877 Website http://melissade.daportfolio.com/ Email [email protected] Passionate about motivating and inspiring children and teens in expression and critical thinking through the arts using the best in comics, animation, illustration, storytelling and design. Always looking to challenge myself, learn from others, and enjoy teaching others about self representation through art. My interests and skills extend over a vast array of genres and fields of professions. I'm looking to continue my career in education to offer the best of my experience and enthusiasm. Education The School of Visual Arts MAT Art Education 2013-2014 BFA Animation 1998-2002 Employment Harper Collins Publishing 2013-2014 Relevant Comic Illustrator Illustrated 7 page black and white comic excerpt for teen novel. Awesome Forces Productions Fall 2012 Assistant Animator Collaborated with partner in creating animation key frames for animated segments featured in TV series entitled The Aquabats! Super Show! Yen Press 2012-current Graphic Novel Illustrator Illustrated a full color chapters for a graphic novel entitled Monster Galaxy. Created and designed new characters along with existing characters in the online game franchise. Random House 2012-2013 Letterer / Retouch Artist Digitally retouched Japanese graphic novels for sub-division, Kodansha. Lettered 200+ comic pages and designed supplemental pages. Organized and prepared interior book files for print production. King Features Syndicate 2006-2010 Comic Strip Illustrator Digitally illustrated, colored and lettered daily comic strip, My Cage, for newspapers across the country from Hawaii to South Africa. Designed numerous characters on a day to day basis for growing cast. -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

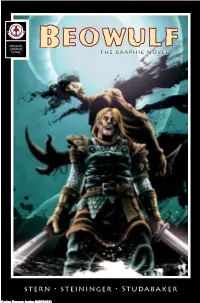

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

Mythology Crossword

Name: _____________________________________ Date: _______ Period: _______ Mythology Crossword 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Across 26. images shown in very large view, often 9. large, full page illustration that introduces a 2. objects used to contain a characters thoughts focusing on a small portion of a larger story 6. comics of non-English origin object/character 11. person who does most/all of the art duties, 10. self contained, book length form of comics 27. The space between each panel/panels implies artist is also writer 15. text labels written on characters in comics Down 12. text that speaks directly to reader 16. text / icons that represent what’s going on in 1. objects used to contain words that character 13. images that are in reverse position from the the characters head speaks previous panel 17. images that show objects fully, from top to 3. rectangles where narrator or character shares 14. One drawing on a page containing a segment bottom special info w/ reader of action 18. person who fills speech balloons and captions 4. term popularized by cartoonists, the medium 19. words that indicate a sounds that accompanies with dialogue/other words is capable of mature, non-comedic content, aswell comic panel as to emphasize hybrid nature of the medium 21. Periodical, normally thin in size and stapled 20. A singular row of panels together 5. images that run outside the border of the panel 23. scripts the work in a way that artist can 22. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

The 2000 AD Script Book Free

FREE THE 2000 AD SCRIPT BOOK PDF Pat Mills,John Wagner,Peter Milligan,Al Ewing,Rob Williams,Dan Abnett,Emma Beeby,Gordon Rennie,Ian Edginton,Alan Grant | 192 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Rebellion | 9781781084670 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The AD Script Book : Pat Mills : Original scripts by leading comics writers accompanied by the final art, taken from the pages of the world famous AD comic. Featuring original script drafts and the final published artwork for comparison, this is a must have for fans of AD and is an essential purchase for anyone interested in writing comics. Pat Mills is the creator and first editor of AD. He wrote Third World War for Crisis! John Wagner The 2000 AD Script Book been scripting for AD for more years than he cares to remember. The 2000 AD Script Book Ewing is a British novelist and American comic book writer, currently responsible for much of Marvel Comics' Avengers titles. He came to prominence with the 1 UK comic AD and then wrote a sequence of novels for Abaddon, of which the El Sombra books are the most celebrated, before becomiing the regular writer for Doctor Who: The Eleventh Doctor and a leading Marvel writer. He lives in York, England. John Reppion has been writing for thirteen years. He is tired. So tired. Will work for beer. By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices. Tell us what you like and we'll recommend books you'll love. -

Colorist Writer Title Page Design Assistant Editor

COLORIST INKER PENCILER MATT YACKEY WRITER MARK FARMER ALAN DAVIS JIM STARLIN COVER LETTERER DAVIS, FARMER & YACKEY VC’S CORY PETIT VARIANT COVER DAN MORA & JESUS ABURTOV EDITOR ASSISTANT EDITOR TOM BREVOORT TITLE PAGE DESIGN ALANNA SMITH CARLOS LAO Editor in Chief: Axel Alonso Chief Creative Officer: Joe Quesada President: Dan Buckley Executive Producer: Alan Fine GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: MOTHER ENTROPY No. 1, July 2017. Published Monthly except in May by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2017 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institu- tions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. $3.99 per copy in the U.S. (GST #R127032852) in the direct mar - ket; Canadian Agreement #40668537. Printed in the USA. Subscription rate (U.S. dollars) for 12 issues: U.S. $26.99; Canada $42.99; Foreign $42.99. POSTMASTER: SEND ALL ADDRESS CHANGES TO GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: MOTHER ENTROPY, C/O MARVEL SUBSCRIPTIONS P.O. BOX 727 NEW HYDE PARK, NY 11040. TELEPHONE # (888) 511-5480. FAX # (347) 537-2649. [email protected]. DAN BUCKLEY, President, Marvel Entertainment; JOE QUESADA, Chief Creative Officer; TOM BREVOORT, SVP of Publishing; DAVID BOGART, SVP of Business Affairs & Operations, Publishing & Partnership; C.B. CEBULSKI, VP of Brand Management & Development, Asia; DAVID GABRIEL, SVP of Sales & Marketing, Publishing; JEFF YOUNGQUIST, VP of Production & Special Projects; DAN CARR, Executive Director of Publishing Technology; ALEX MORALES, Director of Publishing Operations; SUSAN CRESPI, Production Manager; STAN LEE, Chairman Emeritus. -

PERDITIONTO S Tomem Hanksem V Hlavní Roli

Předloha k úspěšnému filmu ROAD TO PERDITION s Tomem Hanksem v hlavní roli MAX ALLAN COLLINS RICHARD PIERS RAYNER CESTA DO PEKEL www.comicscentrum.cz Kliknutím navštívíte internetové stránky Comics Centra. CESTA DO PEKEL ROAD TO PERDITION Napsal: MAX ALLAN COLLINS Nakreslil: RICHARD PIERS RAYNER VěNOVÁNÍ Tuto knihu věnuji svému synovi Nathanovi MAX ALLAN COLLINS Tuto knihu věnuji Richardovi a Jimmymu Překlad z angličtiny: Dana Krejčová – protože otcové milují své děti. Lettering, úprava dialogů, grafická úprava: Martin Trojan RICHARD PIERS RAYNER Úprava dialogů, grafická úprava: Václav Dort Jazykové korektury: Zdenka Štouračová, Eva Hartová Předtisková příprava: Comics Centrum Distribuce: ComicsCentrum NAVšTIVTE NAšE INTERNETOVÉ STRÁNKY: http://www.comicscentrum.cz NEBO NAšI prODEJNU: Štěpánská 36 (Štěpánská pasáž) Praha 1, 110 00 TELEFON: 296 302 570, 296 302 571, FAX: 296 302 573 Z anglického originálu Road to Perdition, vydaného nakladatelstvím DC Comics v roce 1998, českou verzi vydal: Martin Trojan – 3-JAN Štěpánská 36, 110 00 Praha 1 První české vydání © 2006 Vytištěno v České republice ISBN 80-86839-08-7 ROAD TO PERDITION. ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE UNITED STATES BY PARADOX PRESS. SCRIPT COPYRIGHT © 1998 Max Allan Collins. Art Copyright © 1998 Richard Piers Rayner. All rights Reserved. All characters, their distinctive likenesses and related indicia are trademarks of Max Allan Collins. Paradox Press and logo are trademarks of DC Comics. Paradox Press is an imprint of DC Comics. The stories, characters and incidents featured in this publication are entirely fictional. Od začátku 80. let minulého století jsem se syn Nate si ze mě utahoval svou nemilosrdně soustředil hlavně na detektivní řadu s Natha- dobrou náladou, přátelé Marty Greenberg a Ed nem Hellerem. -

Bobby Moore/Pele Photo to Get Artistic Makeover Thanks to Oscar Acclaimed UK Painter Submitted By: Yfppublishing.Com Wednesday, 14 April 2010

Bobby Moore/Pele photo to get artistic makeover thanks to Oscar acclaimed UK painter Submitted by: yfppublishing.com Wednesday, 14 April 2010 Press Release Wednesday 14th April 2010 Mutual Respect/Iconic 1970 Pele & Bobby Moore football photo gets artistic makeover One of the most iconic and endearing sporting photographs ever taken – of footballers Pele and Bobby Moore swapping shirts - is to get an artistic makeover thanks to a renowned artist whose previous work was made into an Oscar and BAFTA-winning film. What’s more you have the opportunity to own a limited-edition print version of the new painting. British artist Richard Piers Rayner illustrated 300-pages of the book ‘Road to Perdition’ which was adapted for the screen by Sam Mendes in 1992 and starred Tom Hanks, Paul Newman and Daniel Craig. Such was his work that Steve Spielberg, who produced the movie, said: “This is great. I don’t even need storyboards. All the work’s been done for me.” Now, football fan Rayner has turned his talent to one of the most famous sporting pictures ever taken. Stockton-born, Rayner has also worked for DC Comics in America on Hellblazer, Batman, Swamp Thing and Legion, and for Marvel illustrating Dr Who, X-Men and Captain America, has now turned to his love of football to give his unique artistry to this memorable image. Rayner says: “I loved the rare and irresistible opportunity to recreate one of sports defining images. In a brief moment at the end of the game opponents acknowledge the sportsmanship of their contest. -

Give Your Letterer a Work-Ready Script!

Presents… The Paradigm I The Paradigm The Paradigm Auteurship in Comics It's been several decades since the late Brandon Tartikoff first identified comic books as the next big thing in dramatic narrative. He was right, of course, but unfortunately too ahead of the curve for three important reasons. One, the technical facility to recreate the fantastical nature of mainstream superhero comics on film or video--and let's not kid ourselves, that's the sort of comics he was talking about--simply didn't yet exist, and two, most of his fellow executives, his senior by ten to twenty five years on average, had little interest at best, and genuine contempt for the material at worst, and were unable to see its potential value. And three, of course, is the tragedy of a very young Tartikoff dropping dead--well before the world in which the comic book would be the driving force behind a billion dollar industry he knew it would come to be. Naturally, none of those billions trickle down to those of us who actually do comics. Rather, it's the descendants of those executives who didn't share Tartikoff's vision that reap the benefits. There are actually a number of people wielding power in Hollywood with an actual lifelong familiarity with comics--but there are far more men-- and a few women, but not many--who used to beat up guys like me in High School for reading comics, now making bank off the same shit they ridiculed. Who said irony was dead, right? And then there's that slew of all too good looking men and staggeringly beautiful women, who put on horn- rimmed glasses and similar paraphernalia so as to convey their "nerdishness" or "geekdom" in order to patronize a readily flattered and easily manipulated swarm of enthusiasts. -

Comic Books: Superheroes/Heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume II: Art, Artifacts, and Material Culture Comic Books: Superheroes/heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images Curriculum Unit 80.02.03 by Patricia Flynn The idea of developing a unit on the American Comic Book grew from the interests and suggestions of middle school students in their art classes. There is a need on the middle school level for an Art History Curriculum that will appeal to young people, and at the same time introduce them to an enduring art form. The history of the American Comic Book seems appropriately qualified to satisfy that need. Art History involves the pursuit of an understanding of man in his time through the study of visual materials. It would seem reasonable to assume that the popular comic book must contain many sources that reflect the values and concerns of the culture that has supported its development and continued growth in America since its introduction in 1934 with the publication of Famous Funnies , a group of reprinted newspaper comic strips. From my informal discussions with middle school students, three distinctive styles of comic books emerged as possible themes; the superhero and the superheroine, domestic scenes, and animal images. These themes historically repeat themselves in endless variations. The superhero/heroine in the comic book can trace its ancestry back to Greek, Roman and Nordic mythology. Ancient mythologies may be considered as a way of explaining the forces of nature to man. Examples of myths may be found world-wide that describe how the universe began, how men, animals and all living things originated, along with the world’s inanimate natural forces. -

Comic Book Crime Truth, Justice, and the American Way

Comic Book Crime Truth, Justice, and the American Way INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE Superman, Batman, Daredevil, and Wonder Woman are iconic cultural figures that em- body values of order, fairness, justice, and retribution. Comic Book Crime digs deep into these and other celebrated characters, provid- ing a comprehensive understanding of crime and justice in contemporary American comic books. This is a world where justice is deliv- ered, where heroes save ordinary citizens from certain doom, where evil is easily identified and thwarted by powers far greater than mere mortals could possess. Nickie Phillips and Sta- ci Strobl explore these representations and show that comic books, as a historically im- portant American cultural medium, participate in both reflecting and shaping an American ideological identity that is often focused on ideas of the apocalypse, utopia, retribution, and nationalism. Through an analysis of approximately 200 comic books sold from 2002 to 2010, as well as several years of immersion in comic book fan culture, Phillips and Strobl reveal the kinds of themes and plots popular comics feature in a post-9/11 context. They discuss heroes’ cal- culations of “deathworthiness,” or who should be killed in meting out justice, and how these judgments have as much to do with the hero’s character as they do with the actions of the villains. This fascinating volume also analyzes how class, race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation are used to construct difference for both the heroes and the villains in ways that are both conservative and progressive. Engag- ing, sharp, and insightful, Comic Book Crime is a fresh take on the very meaning of truth, justice, and the American way.