Political Transitions in the Middle East, Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Rules Governing Assisted Living Licensure

151 1 STATE OF MINNESOTA 2 OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS 3 FOR THE 4 MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 5 6 ---------------------------------------------- 7 In the Matter of: 8 Proposed Rules Governing Assisted Living 9 Licensure and Consumer Protections for Assisted Living Residents, Minnesota Rules, 10 Chapter 4659; Revisor's ID Number R-4605 11 ---------------------------------------------- 12 13 OAH DOCKET NO. 65-9000-37175 14 15 VOLUME II 16 17 The Public Rulemaking Hearing in the 18 above-entitled matter came on via WebEx before 19 Administrative Law Judge Ann C. O'Reilly, taken 20 before Barbara F. Schoenthaler, a Notary Public in 21 and for the County of Washington, State of 22 Minnesota, taken on the 20th day of January, 2021 23 commencing at approximately 9:30 a.m. 24 25 KIRBY KENNEDY & ASSOCIATES (952) 922-1955 152 1 A PPEARANCES 2 3 AGENCY PANEL: 4 JOSH SKAAR, MDH Attorney 5 LINDSEY KRUEGER, Program Manager, Home Care and Assisted Living Program 6 AMY CHANTRY, Legal and Policy Advisor, 7 Health Regulation Division 8 AMY HYERS, Survey Supervisor, Assisted Living Licensure 9 DAPHNE PONDS, Investigator Supervisor, Office of 10 Health Facility Complaints 11 MARIA KING, Assistant Program Manager, Licensing and Certification 12 BEN HANSON, Appeals Coordinator, Background Studies 13 JERI CUMINS, Survey Supervisor, Home Care and 14 Assisted Living Program 15 RICK MICHELS, Licensing and Enforcement Supervisor, Home Care and Assisted Living Program 16 ROBERT DEHLER, Program Manager, Engineer 17 MARK SCHULZ, Legal Specialist, Health Regulation 18 Division 19 JEREMY PEICHEL, Principle/Owner, Civic Intelligence, LLC 20 21 22 23 24 25 KIRBY KENNEDY & ASSOCIATES (952) 922-1955 153 1 I NDEX 2 Page 3 PUBLIC COMMENTS: 4 5 Ms. -

Centennial Year Kicks

Welcome to the Hall NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL ousands of graduates have received an education from the Naval Postgraduate School, and countless more have impacted this university through momen- tous contributions too great to list. But of this extraordinary group of ocers, ocials and leaders, MAGAZINEMAGAZINE there are only nine that have been inducted into the IN RE IEW V JULY 2009 NPS Hall of Fame. Now there are 10. As part of the NPS Centennial Kick-O and Reunion Weekend, General Michael W. Hagee, 33rd Comman- dant of the U.S. Marine Corps and a 1969 Electrical Engineering graduate, was inducted as the tenth member of this illustrious group of inuential leaders. Centennial Year Kicks Off University Begins 100-Year Anniversary Celebration in Grand Style As head of the Marine Corps, Hagee was a tireless supporter of education for the military service. Major General Melvin Spiese, Commanding General of the Marine Corps Training and Education Command, called Hagee “a model of advanced education in the armed forces, and the value it brings to the service member and the service.” And at the Centennial Gala where he was honored, Hagee took the opportunity to reiterate his continuing support. “Today, technology and world events change so fast that we have to educate students for missions that don’t yet exist, to solve problems we don’t yet know, to respond to enemies that can adapt to our plans in seven to 10 days,” he noted during the event. “Innovation is more important than ever, and you can’t innovate without a good advanced educational foundation. -

Huie Dellmon Regular Collection

Huie Dellmon Regular Collection Item No. Subject and Description Date Place 403 Airplanes and crowd of people at airport 404 Air Circus at airport 1929 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 405 Wedell flying his butterfly in air races Baton Rouge, Louisiana 406 Crowds of people at air show 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 407 Air races at airport 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 409 Vapor trails from U. S. bombers over city Alexandria, Louisiana stand pipe 410 Vapor trails from U. S. bombers over city Alexandria, city of stand pipe 1192 Our air show with planes on port 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 1790 Jet Bomber flying at Army Day Show 35mm 8716 Pictures (very small) of a large glider overhead 5/17/1966 Pineville, Louisiana 1717 Aerial picture of aircraft carrier, Forrestal, planes on deck 376 Aerial view of upper part of town from plain farms and etc. 1861 Airplanes Jet F84 crashed in Pineville, LA. in June 1956 on or about 7:35 374 Large U. S. Airplane believed to have flown from Oklahoma camp and got lost out of Dallas, Texas, ran out of gas and landed on upper Third Street 375 Air show at airport Baton Rouge, Louisiana 386 Wrecked Ryan airplane at airport on lower Third Street, belonged to Wedell Williams Co. of Patterson, Louisiana; air service 1920's 388 Windsock for our airport on lower Third Street on Hudson property; not very successful 399 Wrecked Ryan airplane that hit a ditch on port, belongs to Weddell-Williams of Huie Dellmon Regular Collection Patterson, Louisiana 378 Two large B-50's flying low over city and river Alexandria, Louisiana 392 Old Bi-plane at airport 393 People at airport Baton Rouge, Louisiana 394 Parachute dropped at airport, in Enterprise Edition 395 People at airport 396 Large Ryan passenger plane moving on runway 397 Ryan passenger plane and pilot of Weddell Williams Company 398 Planes at airport 400 City Officials at grand opening of airport, lower Third St. -

Inner to Outer Space

Inner to Outer Space From where should NASA or the private industry select their next generation of astronauts? They need individuals with a thirst for adventure, meticulous attention to detail and unbridled enthusiasm for exploration. The best choice for new astronauts lies in the ocean depths. Astronauts and aquanauts (NAUTS) are very similar, and a relationship between the two groups already exists. On a leave of absence from NASA, U.S. Navy astronaut Scott Carpenter worked the “Man in the Sea” project as a team leader in 1965, where he directed the team of divers. Many of the same traits are required for both space and undersea explorers to be successful. From Night Stars to Sea Stars The transfer of desirable habits from using aquanauts to fulfill the role of astronauts would greatly propel space exploration by reducing required training time. Additionally, some of the safety precautions and bailouts used in rebreather and expedition / exploration diving could be useful tools for space exploration. Differences also exist between these two subcultures. Present-day astronauts ride in a large (2 thousand ton) rocket into space, orbiting the earth at 8 kilometers per second at altitudes between 180 and 650 kilometers. Aquanauts descend in a pressurized bell, as free-swimming divers or in a chamber, to depths of between 10 and 600 meters of sea water (msw) at a rate of between 3 and 40 meters per minute; they remain in that high-pressure environment until they decompress. Even the differences have similarities though. When divers descend, the partial pressure of the gases they breathe (oxygen, helium or nitrogen) increases, according to Dalton’s Law. -

Cockrell Bio Current

Biographical Data Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 National Aeronautics and Space Administration SCOTT CARPENTER NASA ASTRONAUT (FORMER) Scott Carpenter, a dynamic pioneer of modern exploration, has the unique distinction of being the first human ever to penetrate both inner and outer space, thereby acquiring the dual title, Astronaut/Aquanaut. He was born in Boulder, Colorado, on May 1, 1925, the son of research chemist Dr. M. Scott Carpenter and Florence Kelso Noxon Carpenter. He attended the University of Colorado from 1945 to 1949 and received a bachelor of science degree in Aeronautical Engineering. Carpenter was commissioned in the U.S. Navy in 1949. He was given flight training at Pensacola, Florida and Corpus Christi, Texas and designated a Naval Aviator in April, 1951. During the Korean War he served with patrol Squadron Six, flying anti-submarine, ship surveillance, and aerial mining, and ferret missions in the Yellow Sea, South China Sea, and the Formosa Straits. He attended the Navy Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, in 1954 and was subsequently assigned to the Electronics Test Division of the Naval Air Test Center, also at Patuxent. In that assignment he flew tests in every type of naval aircraft, including multi- and single-engine jet and propeller-driven fighters, attack planes, patrol bombers, transports, and seaplanes. From 1957 to 1959 he attended the Navy General Line School and the Navy Air Intelligence School and was then assigned as Air Intelligence Officer to the Aircraft Carrier, USS Hornet. Carpenter was selected as one of the original seven Mercury Astronauts on April 9, 1959. -

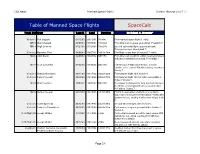

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Photographs Boxes 52 - 110.2; 92 Framed Items

Box Item Location Sub-series Description Photographs Series 10: Photographs Boxes 52 - 110.2; 92 framed items 52 1 01-7-01- Family John H. Glenn, Sr. - child, 1890s-1910s. 23-01-5-1 2 John H. Glenn, Sr. - World War I photographs, circa 1917-1918. 3 John H. Glenn, Sr., 1910s-1940s. 4 John H. Glenn, Sr., 1950s-1960s. 5 John H. Glenn, Sr., automobile accident, Winchester, Virginia., circa 1952-1953. 6 Clara Sproat Glenn, 1900s-1910s. 7 Clara Sproat and John Glenn, Sr., 1910s-1920s. 8 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., 1940s-1950s. 9 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., 1960s. 10 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., with family members, 1940s-1960s. 11 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., various events, 1960s. 12 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., 45th Anniversary Luncheon, April 12, 1962. 13 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., photograph album from the Salvation Army Ohio Service Award Ceremony, May 22, 1962. 14 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., trips, 1920s-1930s. 15 Clara and John H. Glenn, Sr., trips, 1940s. 16 Glenn family, negatives, 1920s-1980s. 17 John C. Glenn (JHG's grandfather), circa 1910s. 18 Ralph and Florence Sproat Thompson (JHG's aunt) family, circa 1930s. 52.1 1 01-7-01- Family Castor family members, 1910s-1940s. 23-01-5- 2 Castor family members, 1950s-1980s. 3 Castor family, unidentified negatives of family members, no date. 4 Homer Castor, photograph album from the American Dental Association's certificate of honor ceremony, October 29, 1962. 1 Box Item Location Sub-series Description Photographs 52.1 5 01-7-01- Family Homer Castor, scrapbook of photographs, newspaper 23-01-5-2 clippings, and correspondence from the American Dental Association's certificate of honor ceremony, October 29, 1962. -

Carpenter Replaces Slayt:On on MA-7

VOL. 1, NO. 11 MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER, LANGLEY STATION, HAMPTON, VA. MARCH 21, 1962 Carpenter Replaces Slayt:on On MA-7 DekeStill In 'ErraticHeart' Cited As Cause Program, Say MSC Officials For Substitution J "I didn'texpecttoviewthisas- 7_lanned Spacecraft Center of- signment with mixed emotions," ficials emphasized last week that - astronaut M. Scott Carpenter told the dcmion to change priors in the newsmen last week. "I hate to be propo,ed :_IA-7 fli,_ht because o[ 1 a part of something which is such Artronaut Donald K. Slaytotfs ir- _ a great disappointment to Deke." reg;dar heartbeat "'would not elimi- nate De/ee from the program." _ _ He referred to Thursday's de- in thk program; right nou ue felt "Deke" Slayton to make the next that other_ u'ho are Jounder at the _ orbital flight. Carpenter, back-up "'There are man)unknouns still _ cisiOnnotto OfallowacivilianAstronautmedicaiDonaldteamK. primoanteeent.'" Puhlicmight Affabirer mOfficerore approJohn- _7 *'- Glenn'spilot duringorbital AsflighttronautFeb.John20, wasH. Power_ lol3 newsnzen at a press Y chosen in Slayton's place "because conference Frida 3. "'When we get to the point where there are not "l the Glenn flight immediately," ac- too many unknou'ns, thi) will not , cording to Public Affairs Officer be ; .li_quali/)ing condition. " : John Powers. "'We expect to &'ep Deke /t)ing Commented Slayton, who learn- ridv ,,¢ .loun the road." ed of the decision late Thursday La&r m ;he u cd_. at ceremonies _ afternoon: "I am quite obviously honoring MSC Director Robert R. _ very disappointed . • I assumed Gilruth and the sez en astronauts in I would go . -

Scott Carpenter Is a True American Hero

Scott Carpenter Bio / Press Scott Carpenter is a true American hero. The first human being to pioneer the frontiers of both inner and outer space, he bears the dual title of Astronaut/Aquanaut. Chosen from a field of 508 military test pilots, Scott Carpenter is one of the original seven NASA Project Mercury astronauts. Commander Carpenter is the second American to orbit the Earth. His 3-orbit, 5-hour mission concluded with a spectacular manual landing after a retrofire malfunction forced a 250- mile overshoot of the planned landing zone. The result: the Aurora 7 spacecraft was outside NASA’s line-of-sight radio range, rendering communication with Cape Canaveral impossible for almost an hour. Anyone who remembers the excitement of the space race of the 1960s will recall the May 24, 1962 television and radio news reports speculating that the astronaut was lost in the Atlantic and his fate unknown. After a long and dramatic 55 minutes, the good news was heralded that Carpenter was discovered alive and well, having emerged from the nose of his spacecraft and settled into a life raft. He was recovered and safely brought aboard the USS Intrepid—two hours after splashdown. Congratulatory calls followed from President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson and the country breathed a mutual sigh of relief. Scott Carpenter was born in Boulder, Colorado on May 1, 1925. He received a bachelor of science degree in Aeronautical Engineering from the University of Colorado, and was commissioned in the U.S. Navy in 1949. This was followed by flight training and service in the Korean War. -

Idstori Diver

Historical Diver, Number 14, 1998 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 10/10/2021 22:26:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30857 IDSTORI DIVER "elf((!} a;k o( wah ,wJ" li lhli- don't du wdhoul haumg bonowEd, ;/o(w, (;u'cha><d a< mad£ a hdm£1 o{ ;o,l>, to g!,mp>< (o' gouud( thli nEw wodd 'Wif(iam 'BEEbE, "'Bwwlh 1~wpio dw/ 1928 Number 14 Winter 1998 Rouquayrol Denayrouze in America • Nick !com's Museum of Diving History • Hans and Lotte Hass • Lloyd Bridges • • Robison Bros. of Melbourne Australia • Christie's Heinke • • Lillian Kimble Patton • DEMA 98 • ADC • Torrance Parker • • Ye Olde Master Divers Locker • De Helmduiker • James Lockwood • HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA HISTORICAL DIVER MAGAZINE A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION ISSN 1094-4516 2022 CLIFF DRIVE# 119 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF SANTA BARBARA, CALIFORNIA 93109 U.S.A. THE HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY U.S.A. PHONE: 805-692-0072 FAX: 805-692-0042 DIVING HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF e-mail: [email protected] or HTTP://WWW.hds.org/ AUSTRALIA, S.E. ASIA ADVISORY BOARD Historical Diving Society Corporate Members Dr. Sylvia Earle Dick Long Dick Bonin J. Thomas Millington, M.D. DIVING SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL Scott Carpenter Bob & Bill Meistrell U.S. DIVERS CO., INC. Jean-Michel Cousteau Bev Morgan D.E.S.C.O. E.R. Cross Phil Nuytten BEST PUBLISHING Andre Galeme Sir John Rawlins MAR-VEL UNDERWATER EQUIPMENT INC. Lad Handelman Andreas B. Rechnitzer Ph.D. SKIN DIVER MAGAZINE Prof. Hans and Lotte Hass Sidney J. -

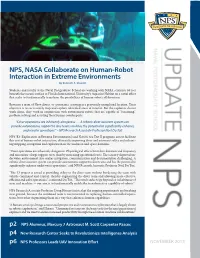

NPS, NASA Collaborate on Human-Robot Interaction in Extreme Environments by Kenneth A

Courtesy Photo NPS, NASA Collaborate on Human-Robot Interaction in Extreme Environments By Kenneth A. Stewart Students and faculty at the Naval Postgraduate School are working with NASA scientists 60 feet beneath the ocean’s surface at Florida International University’s Aquarius Habitat on a novel effort that seeks to fundamentally transform the possibilities of human-robot collaboration. Envision a team of Navy divers, or astronauts, arriving at a previously unexplored location. Their objective is to successively map and explore identified areas of interest. But the explorers do not work alone, they work in conjunction with autonomous robots that are capable of “reasoning,” problem solving and assisting their human counterparts. “Diver operations are inherently dangerous … A robotic diver assistant system can provide autonomous support to dive teams and has the potential to significantly enhance underwater operations.” – NPS Research Associate Professor Noel Du Toit NPS’ E3 (Exploration in Extreme Environments) and NASA’s Sea Test II programs aim to facilitate this sort of human-robot interaction, ultimately improving diver and astronaut safety and enhanc- ing mapping, navigation and exploration in the undersea and space domains. “Diver operations are inherently dangerous. Physiological effects limit dive duration and frequency and necessitate a large support crew, thereby increasing operational costs. The sensory-deprived un- derwater environment also makes navigation, communication and documentation challenging. A robotic diver assistant system can provide autonomous support to dive teams and has the potential to significantly enhance underwater operations,” said NPS Research Associate Professor Noel Du Toit. “The E3 project is aimed at providing utility to the diver team without burdening the team with vehicle command and control, thereby augmenting the diver team and allowing more effective, efficient and safer operations,” continued Du Toit. -

May 13, 2011 Vol

May 13, 2011 Vol. 51, No. 9 Spaceport News John F. Kennedy Space Center - America’s gateway to the universe Cape Crusaders Cabana shares perspective on current, future direction By Linda Herridge supporting NASA’s science support, strap in Spaceport News missions with expendable launch vehicles (ELVs). ennedy Space Currently, there are five Center Director shuttle crew NASA ELV launches re- Bob Cabana told maining this year, and three By Steven Siceloff Not to mention the pure K a packed audience at the Spaceport News excitement that comes with of those will launched from National Space Club Florida nearby Cape Canaveral Air getting ready to go into orbit. Committee luncheon, May he crew of space Force Station. They might not be 10, that NASA is not going shuttle Endeavour will Juno is a five-year mis- thinking so much about out of business and Kennedy climb into the crew strapping themselves into the sion to Jupiter. The Gravity T NASA/Kim Shiflett is not closing its doors after Recovery and Interior Labo- compartment shortly before seats on the shuttle. NASA astronaut Shane Kimbrough is the last space shuttle launch sunrise on Monday ahead of ratory (GRAIL) is a mission “You’ve got your mind in the White Room at Launch Pad 39A during his KSC: Framing the the scheduled liftoff at 8:56 helping the STS-134 crew strap into to the moon and NASA’s on a lot of stuff when you’re Future presentation. a.m. Heading up the launch getting into the shuttle and space shuttle Endeavour during the Mars Science Laboratory Terminal Countdown Demonstration Cabana touched on tower and getting to the getting ready to launch into (MSL) with its Curiosity Test (TCDT) on April 1, just as he will current work including hatch, they will be greeted space,” said astronaut Stan on launch day.