Chris Hadfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Rules Governing Assisted Living Licensure

151 1 STATE OF MINNESOTA 2 OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS 3 FOR THE 4 MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 5 6 ---------------------------------------------- 7 In the Matter of: 8 Proposed Rules Governing Assisted Living 9 Licensure and Consumer Protections for Assisted Living Residents, Minnesota Rules, 10 Chapter 4659; Revisor's ID Number R-4605 11 ---------------------------------------------- 12 13 OAH DOCKET NO. 65-9000-37175 14 15 VOLUME II 16 17 The Public Rulemaking Hearing in the 18 above-entitled matter came on via WebEx before 19 Administrative Law Judge Ann C. O'Reilly, taken 20 before Barbara F. Schoenthaler, a Notary Public in 21 and for the County of Washington, State of 22 Minnesota, taken on the 20th day of January, 2021 23 commencing at approximately 9:30 a.m. 24 25 KIRBY KENNEDY & ASSOCIATES (952) 922-1955 152 1 A PPEARANCES 2 3 AGENCY PANEL: 4 JOSH SKAAR, MDH Attorney 5 LINDSEY KRUEGER, Program Manager, Home Care and Assisted Living Program 6 AMY CHANTRY, Legal and Policy Advisor, 7 Health Regulation Division 8 AMY HYERS, Survey Supervisor, Assisted Living Licensure 9 DAPHNE PONDS, Investigator Supervisor, Office of 10 Health Facility Complaints 11 MARIA KING, Assistant Program Manager, Licensing and Certification 12 BEN HANSON, Appeals Coordinator, Background Studies 13 JERI CUMINS, Survey Supervisor, Home Care and 14 Assisted Living Program 15 RICK MICHELS, Licensing and Enforcement Supervisor, Home Care and Assisted Living Program 16 ROBERT DEHLER, Program Manager, Engineer 17 MARK SCHULZ, Legal Specialist, Health Regulation 18 Division 19 JEREMY PEICHEL, Principle/Owner, Civic Intelligence, LLC 20 21 22 23 24 25 KIRBY KENNEDY & ASSOCIATES (952) 922-1955 153 1 I NDEX 2 Page 3 PUBLIC COMMENTS: 4 5 Ms. -

2013 Winter Newsletter

HHHHHHH LEGACY JOHN F. KENNEDY LIBRARY FOUNDATION Winter | 2013 Freedom 7 Splashes Down at JFK Presidential Library and Museum “I believe this nation should commit itself, to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” – President Kennedy, May 25, 1961 he John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Joined on September 12 by three students from Pinkerton opened a special new installation featuring Freedom 7, Academy, the alma mater of astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr., Tthe iconic space capsule that U.S. Navy Commander Kennedy Library Director Tom Putnam unveiled Freedom 7, Alan B. Shepard Jr. piloted on the first American-manned stating, “In bringing the Freedom 7 space capsule to our spaceflight. Celebrating American ingenuity and determination, Museum, the Kennedy Library hopes to inspire a new the new exhibit opened on September 12, the 50th anniversary generation of Americans to use science and technology of President Kennedy’s speech at Rice University, where he so for the betterment of our humankind.” eloquently championed America’s manned space efforts: Freedom 7 had been on display at the U.S. Naval “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the Academy in Annapolis, MD since 1998, on loan from the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. At the request of hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure Caroline Kennedy, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is the U.S. -

Centennial Year Kicks

Welcome to the Hall NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL ousands of graduates have received an education from the Naval Postgraduate School, and countless more have impacted this university through momen- tous contributions too great to list. But of this extraordinary group of ocers, ocials and leaders, MAGAZINEMAGAZINE there are only nine that have been inducted into the IN RE IEW V JULY 2009 NPS Hall of Fame. Now there are 10. As part of the NPS Centennial Kick-O and Reunion Weekend, General Michael W. Hagee, 33rd Comman- dant of the U.S. Marine Corps and a 1969 Electrical Engineering graduate, was inducted as the tenth member of this illustrious group of inuential leaders. Centennial Year Kicks Off University Begins 100-Year Anniversary Celebration in Grand Style As head of the Marine Corps, Hagee was a tireless supporter of education for the military service. Major General Melvin Spiese, Commanding General of the Marine Corps Training and Education Command, called Hagee “a model of advanced education in the armed forces, and the value it brings to the service member and the service.” And at the Centennial Gala where he was honored, Hagee took the opportunity to reiterate his continuing support. “Today, technology and world events change so fast that we have to educate students for missions that don’t yet exist, to solve problems we don’t yet know, to respond to enemies that can adapt to our plans in seven to 10 days,” he noted during the event. “Innovation is more important than ever, and you can’t innovate without a good advanced educational foundation. -

Huie Dellmon Regular Collection

Huie Dellmon Regular Collection Item No. Subject and Description Date Place 403 Airplanes and crowd of people at airport 404 Air Circus at airport 1929 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 405 Wedell flying his butterfly in air races Baton Rouge, Louisiana 406 Crowds of people at air show 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 407 Air races at airport 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 409 Vapor trails from U. S. bombers over city Alexandria, Louisiana stand pipe 410 Vapor trails from U. S. bombers over city Alexandria, city of stand pipe 1192 Our air show with planes on port 1929 Baton Rouge, city of 1790 Jet Bomber flying at Army Day Show 35mm 8716 Pictures (very small) of a large glider overhead 5/17/1966 Pineville, Louisiana 1717 Aerial picture of aircraft carrier, Forrestal, planes on deck 376 Aerial view of upper part of town from plain farms and etc. 1861 Airplanes Jet F84 crashed in Pineville, LA. in June 1956 on or about 7:35 374 Large U. S. Airplane believed to have flown from Oklahoma camp and got lost out of Dallas, Texas, ran out of gas and landed on upper Third Street 375 Air show at airport Baton Rouge, Louisiana 386 Wrecked Ryan airplane at airport on lower Third Street, belonged to Wedell Williams Co. of Patterson, Louisiana; air service 1920's 388 Windsock for our airport on lower Third Street on Hudson property; not very successful 399 Wrecked Ryan airplane that hit a ditch on port, belongs to Weddell-Williams of Huie Dellmon Regular Collection Patterson, Louisiana 378 Two large B-50's flying low over city and river Alexandria, Louisiana 392 Old Bi-plane at airport 393 People at airport Baton Rouge, Louisiana 394 Parachute dropped at airport, in Enterprise Edition 395 People at airport 396 Large Ryan passenger plane moving on runway 397 Ryan passenger plane and pilot of Weddell Williams Company 398 Planes at airport 400 City Officials at grand opening of airport, lower Third St. -

Inner to Outer Space

Inner to Outer Space From where should NASA or the private industry select their next generation of astronauts? They need individuals with a thirst for adventure, meticulous attention to detail and unbridled enthusiasm for exploration. The best choice for new astronauts lies in the ocean depths. Astronauts and aquanauts (NAUTS) are very similar, and a relationship between the two groups already exists. On a leave of absence from NASA, U.S. Navy astronaut Scott Carpenter worked the “Man in the Sea” project as a team leader in 1965, where he directed the team of divers. Many of the same traits are required for both space and undersea explorers to be successful. From Night Stars to Sea Stars The transfer of desirable habits from using aquanauts to fulfill the role of astronauts would greatly propel space exploration by reducing required training time. Additionally, some of the safety precautions and bailouts used in rebreather and expedition / exploration diving could be useful tools for space exploration. Differences also exist between these two subcultures. Present-day astronauts ride in a large (2 thousand ton) rocket into space, orbiting the earth at 8 kilometers per second at altitudes between 180 and 650 kilometers. Aquanauts descend in a pressurized bell, as free-swimming divers or in a chamber, to depths of between 10 and 600 meters of sea water (msw) at a rate of between 3 and 40 meters per minute; they remain in that high-pressure environment until they decompress. Even the differences have similarities though. When divers descend, the partial pressure of the gases they breathe (oxygen, helium or nitrogen) increases, according to Dalton’s Law. -

Info-Radio.Eu

1 WEEKLY ONLINE HAM RADIO INFORMATION NEWSPAPER EL BOLETIN SEMANAL EN LINEA SOBRE RADIOAFICION Anno 11 - N.ro 20 16 Maggio 2013 www.info-radio.eu https://twitter.com/@INFORADIO1 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEFzhKppZNo www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=80278864777 ON LINE FROM THE 2003 YEAR IN 127 COUNTRIES REALTA' O FANTASCIENZA ? - REAL OR SCIENCE FICTION ? www.centroufologiconazionale.net/ www.livestream.com/cunwebtv 2 Pag. 1 - IN COPERTINA................... L'astronomo Gian Domenico Cassini 2 - ONOMASTICI DEL GIORNO. Nomi vari 3- LEGGENDO QUA E LA......... Da LG una lavatrice che lava senz'acqua 4 - INFO-RADIO NEWS............. NOTIZIE varie 13 - MOSTRE/MERCATI............ Borgo Faiti (LT) - Caltanissetta - Cesena - Torino 18 - V-U-SHF NEWS.................... IAC - Calendari contest - Riptitori D-star 24 - CQ DX................................. INFO varie 25 - ATTIVITA' RADIANTISTICA.. Calendari contest & Classifiche 25 - E.M.E. NEWS........................ DUBUS 6 cm CW EME contest 25 - ATTIVITA' SPAZIALI............. INFO varie 30 - ASTRONOMIA....................... Occhi su Saturno 31 - U.F.O. NEWS......................... INFO varie 32 - L'ANGOLO DEL C.R.T............ INFO & Attività varie 34 - LA PAGINA DEI DIPLOMI....... 9° Diploma “C.O.T.A.” 2013 39 - AWARD NEWS....................... Attivazioni & Informazioni varie 50 - NEWS DAL C.O.T.A................ INFO varie 50 - NEWS DALL'A.R.Fo.P.I........... INFO varie 51 - NEWS DALL'A.R.M.I............... INFO varie 54 - TV CHE PASSIONE!................ Video consigliati - Info-Radio webTV 57 - INFO TECNICHE..................... Grafene bianco, la nuova arma contro le maree nere 58 - INFORMATICA........................ Come avviene il bootstrap di un PC 63 - CURIOSITA' INFORMATICHE... Windows 8.1 in preview a BUILD 2013 65 - TECNOLOGIA........................ -

Manuel De La Mission Expedition 2394 2 SOMMAIRE

Manuel de la mission Expedition 2394 2 SOMMAIRE L'EQUIPAGE La présentation Le Timeline 4 LE VAISSEAU Le vaisseau Soyuz 8 LE LANCEMENT Les horaires Le planning 10 La chronologie de lancement LA MISSION L'amarrage La présentation 16 LE RETOUR L'atterrissage 18 3 Manuel de la mission Expedition 34 L'EQUIPAGE LA PRESENTATION Kevin A. FORD (commandant de bord) Etat civil: Date de naissance: 07/07/1960 Lieu de naissance: Portland (Indiana) Statut familial: Marié et 2 enfants Etudes: Bachelier en ingénierie (University of Notre Dame), Maîtrise en relations internationales (Troy State University), Doctorat en ingénierie astronautique (Air Force Institute of Technology) Statut professionnel: Colonel à l'US Air Force retraité Nasa: Sélectionné comme astrononaute le 10/02/1999 (Groupe 18) Précédents vols : STS128 (13 jours 20:54 d'août à septembre 2009) Oleg V. NOVITSKY (ingénieur de vol) Etat civil: Date de naissance: 12/10/1971 Lieu de naissance: Cherven (Bielorussie) Statut familial: Marié et 1 enfant Etudes: Statut professionnel: Colonel à l'Armed Forces of the Russian Federation retraité Roskosmos: Sélectionné comme cosmonaute le 11/10/2006 (TsPK14) Précédents vols : Manuel de la mission Expedition 34 4 L'EQUIPAGE Yevgeni I. TARELKIN (ingénieur de vol) Etat civil: Date de naissance: 29/12/1974 Lieu de naissance: Pervomaysky (Russie) Statut familial: Marié et 1 enfant Etudes: Diplomé pilote (Vyssheye Voyennoye Aviatsionnoye Uchilishche Lyochikov et Voyenno Vozdushniye Sily) Statut professionnel: Pilote pour le compte du -

Cockrell Bio Current

Biographical Data Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 National Aeronautics and Space Administration SCOTT CARPENTER NASA ASTRONAUT (FORMER) Scott Carpenter, a dynamic pioneer of modern exploration, has the unique distinction of being the first human ever to penetrate both inner and outer space, thereby acquiring the dual title, Astronaut/Aquanaut. He was born in Boulder, Colorado, on May 1, 1925, the son of research chemist Dr. M. Scott Carpenter and Florence Kelso Noxon Carpenter. He attended the University of Colorado from 1945 to 1949 and received a bachelor of science degree in Aeronautical Engineering. Carpenter was commissioned in the U.S. Navy in 1949. He was given flight training at Pensacola, Florida and Corpus Christi, Texas and designated a Naval Aviator in April, 1951. During the Korean War he served with patrol Squadron Six, flying anti-submarine, ship surveillance, and aerial mining, and ferret missions in the Yellow Sea, South China Sea, and the Formosa Straits. He attended the Navy Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, in 1954 and was subsequently assigned to the Electronics Test Division of the Naval Air Test Center, also at Patuxent. In that assignment he flew tests in every type of naval aircraft, including multi- and single-engine jet and propeller-driven fighters, attack planes, patrol bombers, transports, and seaplanes. From 1957 to 1959 he attended the Navy General Line School and the Navy Air Intelligence School and was then assigned as Air Intelligence Officer to the Aircraft Carrier, USS Hornet. Carpenter was selected as one of the original seven Mercury Astronauts on April 9, 1959. -

Political Transitions in the Middle East, Part 1

SHIFTING SANDS: POLITICAL TRANSITIONS IN THE MIDDLE EAST, PART 1 HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE MIDDLE EAST AND SOUTH ASIA OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 13, 2011 Serial No. 112–27 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 65–796PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 16:34 Jul 05, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\MESA\041311\65796 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey HOWARD L. BERMAN, California DAN BURTON, Indiana GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ELTON GALLEGLY, California ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MIKE PENCE, Indiana RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri JOE WILSON, South Carolina ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CONNIE MACK, Florida GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DENNIS CARDOZA, California TED POE, Texas BEN CHANDLER, Kentucky GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEAN SCHMIDT, Ohio ALLYSON SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania BILL JOHNSON, Ohio CHRISTOPHER S. -

International Space Station Facilities Research in Space 2017 and Beyond Table of Contents

National Aeronautics and Space Administration International Space Station Facilities Research in Space 2017 and Beyond Table of Contents Welcome to the International Space Station 1 Program Managers 2 Program Scientists 3 Research Goals of Many Nations 4 An Orbiting Laboratory Complex 5 Knowledge and Benefits for All Humankind 6 Highlights from International Space Station 7 Benefits for Humanity, 2nd Edition What is an ISS Facility? 9 ISS Research History and Status 10 ISS Topology 11 Multipurpose Laboratory Facilities 21 Internal Multipurpose Facilities 23 External Multipurpose Facilities 37 Biological Research 47 Human Physiology and Adaptation Research 65 Physical Science Research 73 Earth and Space Science Research 87 Technology Demonstration Research 95 The ISS Facility Brochure is published by the NASA ISS Program Science Office. Acronyms 100 Executive Editor: Joseph S. Neigut Associate Editor: Judy M. Tate-Brown Index 104 Designer: Cynthia L. Bush NP-2017-04-014-A-JSC Welcome to the International Space Station The International Space Station (ISS) is an unprecedented human achievement from conception to construction, to operation and long-term utilization of a research platform on the frontier of space. Fully assembled and continuously inhabited by all space agency partners, this orbiting laboratory provides a unique environment in which to conduct multidisciplinary research and technology development that drives space exploration, basic discovery and Earth benefits. The ISS is uniquely capable of unraveling the mysteries of our universe— from the evolution of our planet and life on Earth to technology advancements and understanding the effects of spaceflight on the human body. This outpost also serves to facilitate human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit to other destinations in our solar system through continued habitation and experience. -

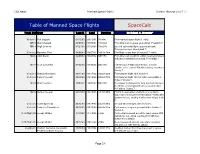

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

EXPEDITION 35 Will Become the First Canadian Commander of the International Space Station

National Aeronautics and Space Administration International Space Station MISSION SUMMARY begins March 15 and ends May 14. Chris Hadfield EXPEDITION 35 will become the first Canadian commander of the International Space Station. The next expedition aboard the orbiting laboratory will be exciting, as astronauts work with new experiments, including the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Cell Mechanosensing and the Canadian Space Agency’s Microflow experiment, the first miniaturized blood-cell counter in microgravity. THE CREW: Soyuz TMA-07M Launch: Dec. 23, 2012 Landing: May 14, 2013 Soyuz TMA-08M Launch: March 28, 2013 Landing: Sept. 11, 2013 Chris Hadfield – Commander (CSA) Pavel Vinogradov – Flight Engineer (Roscosmos) (PA-vel VIN-o-grad-ov) • Born: Sarnia, Ontario, Canada, raised in Milton, • Born: Magadan, Russia Ontario, Canada • Interests: Sports, aviation and cosmonautics history • Interests: Skiing, playing guitar, singing, running and and astronomy playing volleyball • Spaceflights: Mir-24, Exp. 13 & Exp. 35/36 • Spaceflights: STS-74, STS-100, Exp. 34/35 • Twitter: @Cmdr_Hadfield Roman Romanenko – Flight Engineer (Roscosmos) Aleksandr Misurkin – Flight Engineer (Roscosmos) (RO-man Ro-man-yenk-o) (AL-ek-san-der MI-sur-kin) • Born: Schelkovo, Moscow Region, Russia • Born: Yershichi, Smolensk Region, Russia • Interests: Underwater hunting and tennis • Interests: Badminton, basketball and downhill skiing • Spaceflights: Exps. 20/21 and 34/35 • Spaceflights: Exp. 35/36 will be his first mission Tom Marshburn – Flight Engineer (NASA) Chris Cassidy – Flight Engineer (NASA) • Born: Statesville, N.C. • Born: Salem, Mass., but considers York, Maine, • Interests: Swimming, scuba diving and snowboarding to be his hometown • Spaceflights: STS-127, Exp. 34/35 • STS-127 and Exp.