London Parks and Open Spaces Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

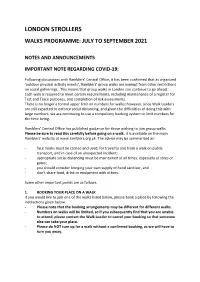

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

210 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

210 bus time schedule & line map 210 Brent Cross, Shopping Centre View In Website Mode The 210 bus line (Brent Cross, Shopping Centre) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Brent Cross, Shopping Centre: 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM (2) Finsbury Park Station: 12:01 AM - 11:49 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 210 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 210 bus arriving. Direction: Brent Cross, Shopping Centre 210 bus Time Schedule 36 stops Brent Cross, Shopping Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM Monday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM Finsbury Park Station (C) Tuesday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM Tollington Park (W) 126 Stroud Green Road, London Wednesday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM Hanley Road / Stapleton Hall Road (CS) Thursday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM 171 Stroud Green Road, London Friday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM Crouch Hill Station / Hanley Road (CP) Saturday 12:05 AM - 11:53 PM Almington Street (E) Hanley Road, London Hornsey Road (F) 210 bus Info 2A Hanley Road, London Direction: Brent Cross, Shopping Centre Stops: 36 Fairbridge Road (N) Trip Duration: 45 min 467 Hornsey Road, London Line Summary: Finsbury Park Station (C), Tollington Park (W), Hanley Road / Stapleton Hall Road (CS), Beaumont Rise (E) Crouch Hill Station / Hanley Road (CP), Almington 6,8 Hillrise Road, London Street (E), Hornsey Road (F), Fairbridge Road (N), Beaumont Rise (E), Mulkern Road, Cressida Road, Mulkern Road Archway Road, Archway Station (W), Whittington 131P St John's Way, London Hospital / Magdala Avenue (A), Waterlow Park -

The Villas 2 FORBURY 3

The Villas 2 FORBURY 3 INSPIRED BY HISTORY, DESIGNED FOR TODAY Located in Blackheath, one of London’s last remaining villages, just over 7 miles* from central London, Forbury is an intimate collection of just twenty, 1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments and ten, 4 bedroom villas in the peaceful setting of Lee Terrace. Set over four floors, the villas feature a spacious, open plan kitchen, dining and family room, a striking master bedroom, en suite bathrooms, light filled living spaces, a rooftop terrace to some homes and private gardens that combine period style with present-day design. The beautiful and vibrant village of Blackheath lies just half a mile* away with excellent connections to London Bridge in just 13 minutes*. The result is a perfectly placed collection of apartments created with modern life in mind. *Distances taken from Google maps and are approximate only. Train times based on an estimated average time. Source: trainline.com Built by Berkeley. Designed for life. 4 FORBURY 5 PERFECTLY LOCATED WITH SPACE TO BREATHE Blackheath Station Canary Wharf University of Greenwich The 02 Greenwich Park Blackheath Common Cutty Sark National Maritime Museum Royal Observatory Greenwich Blackheath Village < Lewisham DLR* Computer enhanced image of Forbury. * Lewisham DLR Station is only 0.8 miles from Forbury. Distances taken from Google maps and are approximate only. Chapter 01 DESIGNED FOR TODAY Visionary homes with every detail carefully considered 8 N SITE PLAN The approach to Forbury from Lee Terrace is defined by a private porte-cochère entrance on the side of the four storey apartment building, which sits above a new concept BMW boutique showroom at street level. -

5. Hampstead Ridge

5. Hampstead Ridge Key plan Description The Hampstead Ridge Natural Landscape Area extends north east from Ealing towards Finsbury and West Green in Tottenham, comprising areas of North Acton, Shepherd’s Bush, Paddington, Hampstead, Camden Town and Hornsey. A series of summits at Hanger Lane (65m AOD), Willesden Green Cemetery (55m AOD) and Parliament Hill (95m AOD) build the ridge, which is bordered by the Brent River to the north and the west, and the Grand Union Canal to the south. The dominant bedrock within the Landscape Area is London Clay. The ENGLAND 100046223 2009 RESERVED ALL RIGHTS NATURAL CROWN COPYRIGHT. © OS BASE MAP key exception to this is the area around Hampstead Heath, an area 5. Hampstead Ridge 5. Hampstead Ridge Hampstead 5. of loam over sandstone which lies over an outcrop of the Bagshot Formation and the Claygate Member. The majority of the urban framework comprises Victorian terracing surrounding the conserved historic cores of Stonebridge, Willesden, Bowes Park and Camden which date from Saxon times and are recorded in the Domesday Book (1086). There is extensive industrial and modern residential development (most notably at Park Royal) along the main rail and road infrastructure. The principal open spaces extend across the summits of the ridge, with large parks at Wormwood Scrubs, Regents Park and Hampstead Heath and numerous cemeteries. The open space matrix is a combination of semi-natural woodland habitats, open grassland, scrub and linear corridors along railway lines and the Grand Union Canal. 50 London’s Natural Signatures: The London Landscape Framework / January 2011 Alan Baxter Natural Signature and natural landscape features Natural Signature: Hampstead Ridge – A mosaic of ancient woodland, scrub and acid grasslands along ridgetop summits with panoramic views. -

Green Linkslinks –– a a Walkingwalking && Cyclingcycling Networknetwork Forfor Southwsouthwarkark

GreenGreen LinksLinks –– A A WalkingWalking && CyclingCycling NetworkNetwork forfor SouthwSouthwarkark www.southwarklivingstreets.org.uk 31st31st MarchMarch 20102010 www.southwarkcyclists.org.uk Contents. Proposed Green Links - Overview Page Introduction 3 What is a Green Link? 4 Objectives of the Project 5 The Nature of the Network 6 The Routes in Detail 7 Funding 18 Appendix – Map of the Green Links Network 19 2 (c) Crown Cop yright. All rights reserved ((0)100019252) 2009 Introduction. • Southwark Living Streets and Southwark Cyclists have developed a proposal for a network of safe walking and cycling routes in Southwark. • This has been discussed in broad outline with Southwark officers and elements of it have been presented to some Community Councils. • This paper sets out the proposal, proposes next steps and invites comments. 3 What is a Green Link? Planting & Greenery Biodiverse Connects Local Safe & Attractive Amenities Cycle Friendly Pedestrian Friendly Surrey Canal Path – Peckham Town Centre to Burgess Park 4 Objectives. • The purpose of the network is to create an alternative to streets that are dominated by vehicles for residents to get about the borough in a healthy, safe and pleasant environment in their day-to-day journeys for work, school shopping and leisure. • The routes are intended to provide direct benefits… - To people’s physical and mental health. - In improving the environment in terms of both air and noise. - By contributing to the Council meeting its climate change obligations, by offering credible and attractive alternatives to short car journeys. - Encouraging people make a far greater number and range of journeys by walking and cycling. • More specifically the network is designed to: - Take advantage of Southwark’s many large and small parks and open spaces, linking them by routes which are safe, and perceived to be safe, for walking and cycling. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

The Park Keeper

The Park Keeper 1 ‘Most of us remember the park keeper of the past. More often than not a man, uniformed, close to retirement age, and – in the mind’s eye at least – carrying a pointed stick for collecting litter. It is almost impossible to find such an individual ...over the last twenty years or so, these individuals have disappeared from our parks and in many circumstances their role has not been replaced.’ [Nick Burton1] CONTENTS training as key factors in any parks rebirth. Despite a consensus that the old-fashioned park keeper and his Overview 2 authoritarian ‘keep off the grass’ image were out of place A note on nomenclature 4 in the 21st century, the matter of his disappearance crept back constantly in discussions.The press have published The work of the park keeper 5 articles4, 5, 6 highlighting the need for safer public open Park keepers and gardening skills 6 spaces, and in particular for a rebirth of the park keeper’s role. The provision of park-keeping services 7 English Heritage, as the government’s advisor on the Uniforms 8 historic environment, has joined forces with other agencies Wages and status 9 to research the skills shortage in public parks.These efforts Staffing levels at London parks 10 have contributed to the government’s ‘Cleaner, Safer, Greener’ agenda,7 with its emphasis on tackling crime and The park keeper and the community 12 safety, vandalism and graffiti, litter, dog fouling and related issues, and on broader targets such as the enhancement of children’s access to culture and sport in our parks The demise of the park keeper 13 and green spaces. -

Superstar Barista Dulwich.Docx

Superstar Barista // Colicci // Dulwich Salary: 9.75 per hour Full time/Shift and rota setup Colicci has been working in partnership with the Royal Parks for over 20 years. We operate stunning catering kiosks and cafes in Kensington Gardens, Hyde Park, Green Park, St James’ Park, Battersea Park, Richmond Park, Bushy Park, Dulwich Park and Peckham Rye Common. We are now looking for a talented Barista to join our busy cafe 'The Dulwich Clock' situated inside Dulwich Park. Searching for a well presented, enthusiastic people with great attitudes who can thrive under pressure, keep a cool head and deliver outstanding customer service at all times. Benefits: beautiful settings to work amongst, reward for top work with high street vouchers, full training academy, career progression, staff food, staff socials Required skills: • Tamping pressure • Ability to make quality expressos • Extraction time • Dialling in the grinder based on changing humidity, temp, and coffee beans. • Ability to operate espresso machine and monitor boiler and dispensing pressure. Ability to steam Milk: • Making microfoam • Steaming to the correct temperature • Altering microfoam for each drink • Dealing with non dairy milk • Sharp latte art You must have minimum 2-3 years experience working as a barista in a similar high volume, fast paced environment! You will be using the La Marzocco Linea PB AV (3 group) Coffee Machine alongside the Mythos 1 grinder. It is not unusual to do 1000+ Coffee/Hot Drinks per day. If you think you have what it takes to be part of this fun, passionate, hard working team then we would love to hear from you! please send us your CV, we'd love to hear from you.. -

101 DALSTON LANE a Boutique of Nine Newly Built Apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN

101 DALSTON LANE A boutique of nine newly built apartments HACKNEY, E8 101 DLSTN 101 DLSTN is a boutique collection of just 9 newly built apartments, perfectly located within the heart of London’s trendy East End. The spaces have been designed to create a selection of well- appointed homes with high quality finishes and functional living in mind. Located on the corner of Cecilia Road & Dalston Lane the apartments are extremely well connected, allowing you to discover the best that East London has to offer. This purpose built development boasts a collection of 1, 2 and 3 bed apartments all benefitting from their own private outside space. Each apartment has been meticulously planned with no detail spared, benefitting from clean contemporary aesthetics in a handsome brick external. The development is perfectly located for a work/life balance with great transport links and an endless choice of fantastic restaurants, bars, shops and green spaces to visit on your weekends. Located just a short walk from Dalston Junction, Dalston Kingsland & Hackney Downs stations there are also fantastic bus and cycle routes to reach Shoreditch and further afield. The beautiful green spaces of London Fields and Hackney Downs are all within walking distance from the development as well as weekend attractions such as Broadway Market, Columbia Road Market and Victoria Park. • 10 year building warranty • 250 year leases • Registered with Help to Buy • Boutique development • Private outside space • Underfloor heating APARTMENT SPECIFICATIONS KITCHEN COMMON AREAS -

Woodwarde Road, Dulwich Village SE22

Woodwarde Road, Dulwich Village SE22 Internal Page 4 Pic Inset Retaining a wealth of period features this property boasts high ceilings, large windows, cornicing and feature fireplaces. The welcoming entrance hall leads to a generous front aspect living room and through to a central further reception/dining room Firstand rear paragraph, kitchen entertainingeditorial style, area short, opening considered on to the headline pretty rear benefitsgarden. The of living ground here. floor One also or offerstwo sentences a handy utility that conveyroom and what youshower would room. say in person. SecondThe upper paragraph, floors provide additional four welldetails proportioned, of note about bright the and airy property.bedrooms Wording and a family to add bathroom. value and Theresupport is alsoimage a homeselection. office/ Temstudy volum on the is first solor floor. si aliquation rempore puditiunto qui utatis adit, animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. Third paragraph, additional details of note about the property. Wording to add value and support image selection. Tem volum is solor si aliquation rempore puditiunto qui utatis adit, animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. XXX X GreatA highly Missenden attractive 1.5 five miles, bedroom London Victorian Marlebone family 39 minutes,home set in a Amershampopular Dulwich 6.5 miles, Village M40 position. J4 10 miles, Beaconsfield 11 miles, M25 j18 13 miles, Central London 36 miles (all distances and times are approximate). Location Woodwarde Road is ideally situated for local transport links. There are excellent connections to the City, Canary Wharf, West End and central London via London Bridge, Victoria, Blackfriars, City Thameslink, Kings Cross/St Pancras either from North Dulwich (0.7 miles) or Herne Hill (1.3 miles). -

The Unification of London

THE RT. HON. G. J. GOSCHEN, M.P., SAYS CHAOS AREA A OF _o_ AND _)w»___x_;_»wH RATES, OF «-uCA__, AUTHORITIES, OF. fa. f<i<fn-r/r f(£sKnyca __"OUR REMEDIEsI OFT WITHIN OURSELVES DO LIE." THE UNIFICATION OF LONDON: THE NEED AND THE REMEDY. BY JOHN LEIGHTON, F.S.A. ' LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT IS A CHAOS OF AUTHORITIES,OF RATES, — and of areas." G. jf. Goscheu London: ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, CITY 1895. To The Right Hon. SIR JOHN LUBBOCK, P.C., M.P., HON. LL.D. (CAMB., EDIN., AND DUB.), F.R.S., F.S.A., F.G.S., M.R.I., V.P.E.S., Trustee of the British Museum,Commissioner of Lieutenancy for London, THIS BOOK is dedicated by CONTENTS. PAGE Chapter — I.— The Need 7 II. The Remedy ... — ... n III.— Local Government ... 17 IV. Conclusion 23 INDEX PAGE PAGE Abattoirs ... 21 Champion Hill 52 Address Card 64 Chelsea ... ... ... 56 Aldermen iS City 26 Aldermen, of Court ... 19 Clapham ... ... ... 54 AsylumsBoard ig Clapton 42 Clerkenwell 26 Barnsbury ... ... ... 29 Clissold Park 4U Battersea ... ... ... 54 Coroner's Court 21 Battersea Park 56 County Council . ... 18 Bayswater 58 County Court ... ... 21 Bermondsey 32 BethnalGreen 30 Bloomsbury 38 Dalston ... ... ... 42 Borough 34 Deptford 48 Borough Council 20 Dulwich 52 Bow 44 Brixton 52 Finsbury Park 40 Bromley ... 46 Fulham 56 Cab Fares ... ... ... 14 Gospel Oak 02 Camberwell 52 Green Park Camden Town 3S Greenwich ... Canonbury 28 Guardians, ... Board of ... 20 PAGE PAGE Hackney ... ... ... 42 Omnibus Routes ... ... 15 Hampstead... ... ... Co Hatcham ... 50 Paddington 58 Haverstock Hill .. -

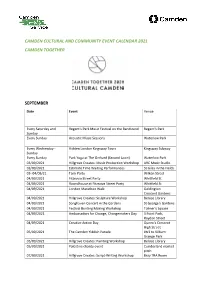

Camden Cultural and Community Event Calendar 2021 Camden Together

CAMDEN CULTURAL AND COMMUNITY EVENT CALENDAR 2021 CAMDEN TOGETHER SEPTEMBER Date Event Venue Every Saturday and Regent's Park Music Festival on the Bandstand Regent's Park Sunday Every Sunday Acoustic Music Sessions Waterlow Park Every Wednesday - Hidden London Kingsway Tours Kingsway Subway Sunday Every Sunday Park Yoga at The Orchard (Second Lawn) Waterlow Park 03/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 03/09/2021 Estimate Time Waiting Performances St Giles in the Fields 03- 04/09/21 Tank Party Wilken Street 04/09/2021 Fitzrovia Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 Roundhouse at Fitzroiva Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 London Marathon Walk Goldington Crescent Gardens 04/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Sculpture Workshop Belsize Library 04/09/2021 Songhaven Concert in the Gardens St George's Gardens 04/09/2021 Festival Bunting Making Workshop Tolmer's Square 04/09/2021 Ambassadors for Change, Changemakers Day 3 Point Park, Raydon Street 04/09/2021 Creative Action Day Queen's Crescent High Street 05/09/2021 The Camden Yiddish Parade JW3 to Kilburn Grange Park 05/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Painting Workshop Belsize Library 05/09/2021 Palestine charity event Cumberland market pitch 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Script-Writing Workshop Bray TRA Room 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 08/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Theatre Performance Belsize Library Workshop 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production