South China Sea Issue in China-ASEAN Relations: an Alternative Approach to Ease the Tension+

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Long Littoral Project: South China Sea a Maritime Perspective on Indo-Pacific Security

The Long Littoral Project: South China Sea A Maritime Perspective on Indo-Pacific Security Michael A. McDevitt • M. Taylor Fravel • Lewis M. Stern Cleared for Public Release IRP-2012-U-002321-Final March 2013 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “problem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Administrative Order No. 29 Naming the West Philippine Sea of The

MALACAÑAN PALACE MANILA BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE PHILIPPINES ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER NO. 29 NAMING THE WEST PHILIPPINE SEA OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES WHEREAS, Presidential Decree No. 1599 (1978) established the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the Philippines extending to a distance of two hundred nautical miles from the baselines of the Philippine archipelago; WHEREAS, Republic Act No. 9522 (2009), or the Baselines Law, specifically defined and described the baselines of the Philippine archipelago; WHEREAS, the Philippines exercises sovereign rights under the principles of international law, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to explore and exploit, conserve and manage the natural resources, whether living or non-living, both renewable and non-renewable, of the sea-bed, including the subsoil and the adjacent waters, and to conduct other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of its maritime domain, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds; WHEREAS, the Philippines exercises sovereign jurisdiction in its EEZ with regard to the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures; marine scientific research; protection and preservation of the marine environment; and other rights and duties provided for in UNCLOS; and WHEREAS, in the exercise of sovereign jurisdiction, the Philippines has the inherent power and right to designate its maritime areas with appropriate nomenclature for purposes of the national mapping system. NOW, THEREFORE, I, BENIGNO S. AQUINO III, President of the Philippines, by virtue of the powers vested in me by the Constitution and by law, do hereby order: Section 1. -

The South China Sea Arbitration Case Filed by the Philippines Against China: Arguments Concerning Low Tide Elevations, Rocks, and Islands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Xiamen University Institutional Repository 322 China Oceans Law Review (Vol. 2015 No. 1) The South China Sea Arbitration Case Filed by the Philippines against China: Arguments concerning Low Tide Elevations, Rocks, and Islands Yann-huei SONG* Abstract: On March 30, 2014, the Philippines submitted its Memorial to the Arbitral Tribunal, which presents the country’s case on the jurisdiction of the Tribunal and the merits of its claims. In the Memorial, the Philippines argues that Mischief Reef, Second Thomas Shoal, Subi Reef, Gaven Reef, McKennan Reef, Hughes Reef are low-tide elevations, and that Scarborough Shoal, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Fiery Cross Reef are “rocks”, therefore these land features cannot generate entitlement to a 200-nautical-mile EEZ or continental shelf. This paper discusses if the claims made by the Philippines are well founded in fact and law. It concludes that it would be difficult for the Tribunal to rule in favor of the Philippines’ claims. Key Words: Arbitration; South China Sea; China; The Philippines; Low tide elevation; Island; Rock; UNCLOS I. Introduction On January 22, 2013, the Republic of the Philippines (hereinafter “the Philippines”) initiated arbitral proceedings against the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter “China” or “PRC”) when it presented a Note Verbale1 to the Chinese * Yann-huie Song, Professor, Institute of Marine Affairs, College of Marine Sciences, Sun- yet Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan and Research Fellow, Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected]. -

Tides of Change: Taiwan's Evolving Position in the South China

EAST ASIA POLICY PAPER 5 M AY 2015 Tides of Change: Taiwan’s evolving position in the South China Sea And why other actors should take notice Lynn Kuok Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment, and the analysis and recommendations of the Institution’s scholars are not determined by any donation. Executive Summary aiwan, along with China and four Southeast The People’s Republic of China (PRC) inherited its Asian countries, is a claimant in the South claims from the Republic of China (ROC) after the TChina Sea, though this fact is sometimes Chinese civil war. Thus, the ROC’s interpretation overlooked. On paper, Taiwan and China share of its claims is relevant to the PRC’s claims. No- the same claims. The dashed or U-shaped line en- tably, a more limited reading of the claims would capsulating much of the South China Sea appears not be inconsistent with China’s official position on both Taiwanese and Chinese maps. as set out in its 2009 and 2011 statements to the United Nations. Neither China nor Taiwan has officially clarified the meaning of the dashed line which could be Taiwan’s overtures have largely, however, been ig- seen as making a claim to the wide expanse of wa- nored. At the root of this is China’s “one-China” ter enclosed within the dashed line or (merely) to principle, which has cast a long shadow over Tai- the land features contained therein and to mari- wan. -

US-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas

U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42784 U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas Summary Over the past several years, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island-building and base- construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan- administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere. Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. -

Bill No. ___ an ACT IDENTIFYING the PHILIPPINE MARITIME

Bill No. ___ AN ACT IDENTIFYING THE PHILIPPINE MARITIME FEATURES OF THE WEST PHILIPPINE SEA, DEFINING THEIR RESPECTIVE APPLICABLE BASELINES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES* EXPLANATORY NOTE In a few weeks, the country will mark the 5th year of the Philippines’ victory against China in the South China Sea (SCS) Arbitration. The Arbitral Award declared that China's Nine-Dash Line claim violates the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).1 It declared that the Philippines has an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and Continental Shelf (CS) in the areas of Panganiban (Mischief) Reef, Ayungin (Second Thomas) Shoal and Recto (Reed) Bank, and that Filipino fishermen have traditional fishing rights, in common with Chinese and Vietnamese fishermen, in the Territorial Sea (TS) of Bajo de Masinloc. Yet, the Philippines has remained unable to translate its victory into actual exercise of exclusive sovereign rights over fishing and resource exploitation in its recognized EEZ and CS and traditional fishing rights in the TS of Bajo de Masinloc. This proposed new baselines law seeks to break that impasse Firstly, it identifies by name and coordinates at least 100 features being claimed and occupied by the Philippines. This is an exercise of acts of sovereignty pertaining to each and every feature, consistent with the requirements of international law on the establishment and maintenance of territorial title. Secondly, it adopts normal baselines around each feature that qualifies as a high- tide elevation. This is to delineate the TS of each of said feature. Thirdly, it reiterates continuing Philippine sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction, as appropriate, over these features. -

Mutating Philippine Foreign Policy on the South China Sea: Tracing Continuity and Breaks*

Mutating Philippine Foreign Policy on the South China Sea: Tracing Continuity and Breaks* Rhisan Mae E. Morales, MAIS Assistant Professor I International Studies Department Social Science Cluster Ateneo de Davao University Philippines +629995133922, (082)221-2411 loc 8322 _______________________________________________________________ Abstract Keywords: South China Sea, Scarborough Standoff, Philippine Foreign Policy, The approaches of Philippines claims in the South China Sea depend on the policies of different administration since Ferdinand Marcos. Given the political and security landscape of the country resulting to various interests that influenced the foreign policy, responses of each administration has degree of variations. Philippine foreign policy consistently adheres to the principles of national interest and territorial integrity as articulated by the Constitution. However, it failed to establish a long term approach that pursues an ensuring and continuous mechanism that will fortify our sovereign claims over the area. This paper will provide a historical development of the Philippine claims in the South China Sea from the administrations of Ferdinand Marcos to Benigno “Pnoy” Aquino. Additionally, this paper will identify the foreign policies and the different approaches acted upon by each administration to assert claims in the South China Sea. Findings of this study proved that the Philippines outlined several approaches to address territorial concerns in the South China Sea. There has been a continuity of policies but not articulated as law; hence it depends on the serving administration. One of the identified long term policy since 1994 was the National Marine Policy but was dormant until the Scarborough Standoff in 2012. *A summary of a chapter from a thesis entitled Philippine Foreign Policy in the West Philippine Sea After the Scarborough Standoff: Implications for National Security. -

SBN-376 (As Filed)

EIGHTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE ) ■?, cT- ( f . i v ; ■■ REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) ' T; ■ c f!; k .. ct.'-r * First Regular Session ) '19 JUL 11 P 2 :4 2 SENATE S. No. 3 7 6 Introduced by SENATOR LEILA M. DE LIMA AN ACT DECLAIUNG JULY 12 OI EVERY YEAR AS A SPECIAL WORKING HOLIDAY IN THE ENTIRE COUNTRY TO COMMEMMORATE THE HISTORIC DECISION OE THE PERMANENT COURT OF ARBITRATION (PCA) IN FAVOR OF PHILIPPINE SOVEREIGNTY OVER THE WEST PHILIPPINE SEA EXPLANATORY NOTE The South China Sea has been one of the most strategic waterways in the world with decades-long history of maritime dispute among seven (7) claimant countries, including the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China. One of the persistent issues over this disputed territory is China’s controversial "historical" claim, outlined by a 9-dash line affecting almost 90 percent of the contested waters. The said line runs as far as 2,000 kilometers from the Chinese mainland to within a few hundred kilometers from territories of other claimant countries, such as the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam. The People’s Republic of China maintains their stand that it owns any land or features contained within that line1. China’s sabre-rattling in the disputed maritime territory aggravated the situation with reported harassments by Chinese patrol boats in 2011 and China’s take-over of Scarborough Shoal (which forms part of the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone) in 20122. Amid the heightening conflict, the Philippines has 1 Zhen L. (12 July 2016) What’ s China' s ‘ nine-dash line ’ and why has it created so much tension in the South China Sea?. -

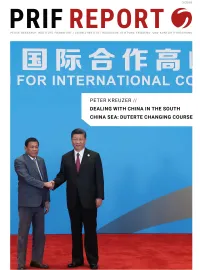

Dealing with China in the South China Sea. Duterte Changing Course

PRIF Report 3/2018 DEALING WITH CHINA IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA DUTERTE CHANGING COURSE PETER KREUZER // ImprInt LEIBNIZ-INSTITUT HESSISCHE STIFTUNG FRIEDENS- UND KONFLIKTFORSCHUNG (HSFK) PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE FRANKFURT (PRIF) Cover: Chinese President Xi Jinping welcomes Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte before the Leaders’ Roundtable Summit of the Belt and Road Forum (BRF) for International Cooperation at Yanqi Lake; © picture alliance / Photoshot. Text license: Creative Commons CC-BY-ND (Attribution/NoDerivatives/4.0 International). The images used are subject to their own licenses. Correspondence to: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt Baseler Straße 27–31 D-60329 Frankfurt am Main Telephone: +49 69 95 91 04-0 E-Mail: [email protected] https://www.prif.org ISBN: 978-3-946459-31-6 Summary Recapitulating the developments of the past years of escalation and the surprisingly successful de-escalation of Sino-Philippine relations since mid-2016, this report ponders the broader question of how to deal prudently with an assertive China in the South China Sea. From 2011 to 2016 the multilateral conflict over territorial sovereignty and maritime rights in the South China Sea intensified dramatically. At its core are China and the Philippines, since the latter took the unprecedented step of bringing a case before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) against China in early 2013, against the express desire of its opponent. The aftermath of this step was that bilateral relations chilled to an all-time-low, with China retali- ating by escalating its activity in the disputed areas: small low-tide elevations were transformed into huge artificial islands and equipped with fortified harbors and airports that massively extend the op- erational capacity of the Chinese Navy and Airforce. -

Managing Tensions in the South China Sea” Conference Held by CSIS on June 5-6, 2013

This paper was submitted by the author for the “Managing Tensions in the South China Sea” conference held by CSIS on June 5-6, 2013. The views expressed are solely those of the author, and have not been edited or endorsed by CSIS or the Sumitro Chair for Southeast Asia Studies. 2 Recent Developments in the South China Sea: Taiwan’s Policy, Response, Challenges and Opportunities Yann-huei Song* “Just as German soil constituted the military front line of the Cold War, the waters of the South China Sea may constitute the military front line of the coming decades.” “The 21st century's defining battleground is going to be on water” and “the South China Sea is the Future of Conflict.” – Robert D. Kaplan1 “Governance of the South China Sea presents challenges. The countries of the region as well as those with interests in these regions must work together to manage and protect these shared ocean spaces for the benefit of present and future generations.” – Jon M. Van Dyke2 Introduction In the light of recent developments in the South China Sea, there is an urgent need for the governments and policy makers of the countries that border this important body of water and other countries that are considered “outsiders” in the South China Sea dispute to take note seriously of the warning and recommendation made by Kaplan and Van Dyke, respectively, in 2011. If not managed well, the possibility for the territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea to be erupted into serious armed conflicts cannot be ruled out. -

Great Power Conflict in the Western Pacific: Reprise of the First World War Scenario?

Expert Analysis January 2014 Great power conflict in the western Pacific: reprise of the First World War scenario? By Walden Bello Executive summary The Asia-Pacific region has entered a period of destabilising conflict. In the last few weeks, China’s unilateral imposition of an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over a large part of the East China Sea has been the centre of controversy. Beijing’s ADIZ declaration came in the wake of worsening relations with Japan owing to rival claims over the Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands. Further south, the attention of geopolitical analysts has focused on the Philippines, which is quickly becoming a frontline state in the U.S. strategy to contain China, the central thrust of the so-called pivot to Asia promoted by the Obama administration. In the most recent development, the Philippine government has offered the United States greater access to its military bases.1 Serving as a convenient excuse for a heightened U.S. it claims belongs to China. Among these are the Spratly military presence in the region have been China’s contro- Islands, nine of which are claimed and occupied by the versial moves in the western Pacific. In particular, Beijing’s Philippines, along with Scarborough Shoal, Ayungin Shoal, claiming the whole South China Sea, or West Philippine Panganiban Reef and Recto Bank, all of which are claimed Sea as Chinese territory has allowed the United States to by the Philippines. The last few months have seen a series come in and appear an indispensable actor to protect the of provocative Chinese moves, including occupation of region’s smaller countries against Chinese hegemony. -

Concrete Solutions to the Maritime Disputes Between the Philippines and China Prof

Concrete Solutions to the Maritime Disputes between the Philippines and China Prof. dr. Jay L. Batongbacal University of the Philippines Institute for Maritime Affairs & Law of the Sea Introduction Ladies and gentlemen, good morning. Thank you for inviting me to this conference in Oxford on what remains the most complicated territorial and maritime disputes in the world, the South China Sea disputes. I hope that this discussion will enable us to see our way forward on some, if not all, the varied practical, legal, political, environmental, and regional relations issues that we have been hearing about since yesterday. I have been asked to discuss concrete solutions to the maritime disputes particularly between the Philippines and China. This is daunting task, but I will try to encapsulate years of observations about the reasons behind the two countries’ disputes, and try to make realistic recommendations. Interests at Stake I begin with describing broadly the competing interests at stake for each party. First, the Philippines The Philippines remains a developing country with a growing population of over 100 Million, scattered across 7,500 islands in a compact marine region rich with marine resources directly accessed by coastal communities. Its principal interests in the SCS, or more specifically its EEZ that is referred to as the West Philippine Sea, are best described, in order of priority more or less, as (1) energy security,, (2) food security, and (3) maritime security. Energy security appears to be the primary driver of the Philippines decision to throw its hat into the SCS disputes in the late 1960s.