STUDY TOUR to DUTCH NEW COMMUNITIES July 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

180329 Geitenhouderij En Gezondheid-Adviesggd Regio Utrecht

Geitenhouderij en gezondheid – Advies GGD regio Utrecht 29 maart 2018 Aanleiding In het RIVM rapport “Veehouderij en gezondheid omwonenden (aanvullende studies)” 1 (VGO2) van juni 2017 is een statistisch significante relatie gevonden tussen het wonen nabij een geitenhouderij (variërend van 1,5 tot 2 kilometer) en een verhoogd risico op het krijgen van longontsteking. Deze verhoging wordt gezien in alle jaren in de onderzochte periode van 2009 tot en met 2013, waardoor de kans dat dit op toeval berust klein is. Het is niet duidelijk wat de oorzaak is van dit verhoogde risico. Naar aanleiding van het VGO2 rapport hebben de provincies Noord-Brabant en Gelderland besloten om voorlopig geen nieuwvestiging of uitbreiding van geitenhouderijen toe te staan. In het verlengde daarvan heeft de provincie Utrecht aan de GGD regio Utrecht verzocht om een duiding te geven van het gezondheidsrisico rondom geitenhouderijen voor de bewoners van de provincie Utrecht. Conclusie aanvullende studies Er wordt een consistent verband gevonden tussen de aanwezigheid van (melk)geitenhouderijen op woonafstanden van 1,5 tot 2 kilometer en een verhoogd risico op longontsteking, in alle jaren 2009 tot en met 2013. Ook rondom pluimveehouderijen zijn in het onderzoek meer longontstekingen gevonden (tot een afstand van 1,5 kilometer). Er zijn geen consistente verbanden gevonden tussen het optreden van longontsteking en de aanwezigheid van nertsen-, rundvee-, schapen- en varkensbedrijven. De onderzoekers concluderen dat deze verhogingen geen relatie met Q-koorts hebben. Het is op dit moment nog onduidelijk wat de precieze oor zaak is van het hogere risico op longontsteking in de omgeving van geitenhouderijen. Advies De GGD regio Utrecht onderschrijft de conclusie uit het VGO onderzoek dat het verhoogd voorkomen van longontsteking rondom geitenhouderijen zorgelijk is, mede omdat niet duidelijk is waardoor dit wordt veroorzaakt. -

Utrecht CRFS Boundaries Options

City Region Food System Toolkit Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems CITY REGION FOOD SYSTEM TOOLKIT TOOL/EXAMPLE Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and RUAF Foundation and Wilfrid Laurier University, Centre for Sustainable Food Systems May 2018 City Region Food System Toolkit Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems Tool/Example: Utrecht CRFS Boundaries Options Author(s): Henk Renting, RUAF Foundation Project: RUAF CityFoodTools project Introduction to the joint programme This tool is part of the City Region Food Systems (CRFS) toolkit to assess and plan sustainable city region food systems. The toolkit has been developed by FAO, RUAF Foundation and Wilfrid Laurier University with the financial support of the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Daniel and Nina Carasso Foundation. Link to programme website and toolbox http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/overview/what-we-do/en/ http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/toolkit/introduction/en/ http://www.ruaf.org/projects/developing-tools-mapping-and-assessing-sustainable-city- region-food-systems-cityfoodtools Tool summary: Brief description This tool compares the various options and considerations that define the boundaries for the City Region Food System of Utrecht. Expected outcome Definition of the CRFS boundaries for a specific city region Expected Output Comparison of different CRFS boundary options Scale of application City region Expertise required for Understanding of the local context, existing data availability and administrative application boundaries and mandates Examples of Utrecht (The Netherlands) application Year of development 2016 References - Tool description: This document compares the various options and considerations that define the boundaries for the Utrecht City Region. -

Gebiedsdossier Waterwinning Leidsche Rijn

Naarden Huizerhoogt! Amstelveen Aalsmeer Abcoude Nigtevecht! Bussum ! Hilversumse! Crailo Blaricum Meent TITEL Eempolder ! 0 2,5 km Nederhorst! Ankeveen den Berg DOMEIN LEEFOMGEVING, TEAM GIS | ONDERGROND: 2020, KADASTER | 06-1 1 -20 | 1 234501 | A0 Nes ! aan de Amstel Putten Grondwaterbescherming Eemnes Laren Eemdijk! Boringsvrije zone 100-jaarsaandachtsgebied Baambrugge! Uithoorn Waterwingebied 's-Graveland! Bunschoten-Spakenburg Grondwaterbeschermingsgebied ! Kortenhoef WaterwingebiedKrachtighuizen (bijz. regels) Amstelhoek! ! Loenersloot! Vreeland ! Waverveen! Kerklaan! Hilversum Huinen Nijkerk Baarn Loenen! aan de Vecht Vinkeveen Oud-Loosdrecht! Mijdrecht De Hoef! ! Nieuw-Loosdrecht Holkerveen Wilnis Nieuwersluis! Nijkerkerveen! Nieuwer! Ter Aa Boomhoek! Hoogland Muyeveld! Voorthuizen ! Breukelen Scheendijk Lage Vuursche! Zwartebroek! Breukeleveen! Hollandsche! Rading Hoevelaken ! Tienhoven Soest ! ! Amersfoort Terschuur Noorden GEBIEDSDOSSIER Amersfoort-Koedijkerweg ! Portengensebrug Bethunepolder Oud-Maarsseveen! Maartensdijk! ! WATERWINNING Woerdense Verlaat Stoutenburg! LEIDSCHE RIJN Westbroek! Kockengen! ! Maarsseveen! Molenpolder Soestduinen Amersfoort-Berg ! Den Dolder Barneveld ! Maarssen Achterveld Leusden Groenekan Bilthoven Oud Zuilen! Kanis! ! Haarzuilens Groenekan! ! Beukbergen De Glind! ! Huis! ter Soesterberg Leusden-Zuid Heide ! Kamerik! Sterrenberg Zegveld! Beerschoten De Bilt Leidsche Rijn Vleuten Zeist Woerden Zeist Harmelen Utrecht De Meern Lunteren Woudenberg Scherpenzeel ! Nieuwerbrug! Austerlitz aan den Rijn -

Annex 3, Case Study Randstad

RISE Regional Integrated Strategies in Europe Targeted Analysis 2013/2/11 ANNEX 3 Randstad Case Study | 15/7/2012 ESPON 2013 This report presents the final results a Targeted Analysis conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2013 Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The partnership behind the ESPON Programme consists of the EU Commission and the Member States of the EU27, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Each partner is represented in the ESPON Monitoring Committee. This report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the Monitoring Committee. Information on the ESPON Programme and projects can be found on www.espon.eu The web site provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. This basic report exists only in an electronic version. © ESPON & University of Birmingham, 2012. Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON Coordination Unit in Luxembourg. ESPON 2013 ANNEX 3 Randstad Case Study: The making of Integrative Territorial Strategies in a multi-level and multi-actor policy environment ESPON 2013 List of authors Marjolein Spaans Delft University of Technology – OTB Research Institute for the Built Environment (The Netherlands) Bas Waterhout Delft University of Technology – OTB Research Institute for the Built Environment (The Netherlands) Wil Zonneveld Delft University of Technology – OTB Research Institute for the Built Environment (The Netherlands) 2 ESPON 2013 Table of contents 1.0 Setting the scene for RISE in the Randstad ............................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 1.2 Governance in the Randstad ........................................................... -

Vestingstad Ijsselstein

V estingstad IJsselstein ADVIESGROEP BB+W VESTINGSTAD IJSSELSTEIN 1 HISTORISCHE KRING IJSSELSTEIN Dit plan 'Vestingstad IJsselstein' is tot stand gekomen in samenwerking met Stichting Historische Kring IJsselstein (HKIJ). De HKIJ beijvert zich o.a. voor het behoud van de zichtbare en immateriële cultuurhistorische identiteit van IJsselstein en omgeving. Het plan Vestingstad IJsselstein is een doorontwikkeling van eerdere initiatieven van de HKIJ die in het recente verleden tot beeldbepalende resultaten hebben geleid daar waar het de oorspronkelijke vestingwerken betreft. Meer info over het werk van de HKIJ: www.hkij.nl. Inspiratiedocument met als doel: MUSEUM IJSSELSTEIN Museum IJsselstein (MIJ) vertelt het verhaal aanwijzing van verleden, heden en toekomst van IJsselstein en de wereld. Hoe duidelijker het verhaal van Gemeentelijk Monument Vestingstad IJsselstein ‘Vestingstad IJsselstein’ in de binnenstad zichtbaar is hoe beter onze veelzijdige IJsselsteinse geschiedenis voor de eigentijdse mens tot leven en komt. YSELVAERT realisatie Yselvaert vaart al vele jaren door de prachtige stads gracht van IJsselstein. ‘Vestingstad IJsselstein’ van een aaneengesloten reeks markeringen, laat de middeleeuwse gracht, de verhalen in en reconstructies en visualiseringen over Kasteel IJsselstein en onze rijke geschiedenis nog meer tot de verbeelding spreken. die herinneren aan de middeleeuwse vestingwerken STADSMARKETING van Vestingstad IJsselstein. De historische binnenstad is voor Stadsmarketing IJsselstein een van de belangrijkste kernwaarden. Realisatie van ‘Vestingstad IJsselstein’ zal een positieve impuls geven om IJsselstein in stad, regio en in het land nog prominenter op de kaart te zetten. Dat is goed voor de economie, de bewoners en het culturele leven van de stad. ‘UIT in IJsselstein’ zet zich in om bezoekers en toeristen uit het hele land de leukste en mooiste plekjes van onze stad te laten ervaren. -

Gemeentepagina Week 30

Gemeentenieuws Nieuws over Corona Nieuws over corona voor inwoners en ondernemers De gemeente informeert u over de ontwikkelingen rondom het coronavirus en steunmaatregelen voor ondernemers. Kijk hiervoor op www.derondevenen.nl/corona Vragen over het coronavirus of vaccinatie? U kunt terecht bij ▪ het RIVM: www.rivm.nl/coronavirus ▪ de GGD regio Utrecht: www.ggdru.nl/corona of 030 - 630 54 00 (doordeweeks tussen 8.30 en 17.00 uur, in het weekend tussen 9.00 en 16.00 uur) ▪ het landelijk informatienummer: 0800 - 13 51 (tussen 8.00 en 20.00 uur). ▪ www.rijksoverheid.nl/corona Werkzaamheden Vinkeveen, verkeershinder Herenweg De Herenweg is ter hoogte van huisnummer 71 van 2 augustus 7.00 uur tot en met 3 augustus 16.00 uur gedeeltelijk afgesloten. Het verkeer zal worden geregeld met verkeersregelaars en winkels en bedrijven zijn gewoon bereikbaar. Deze maatregel is nodig voor het repareren van de waterleiding naar aanleiding van de calamiteit enige weken geleden. Er is geprobeerd de werkzaamheden gelijktijdig op 29 en 30 juli met Volker Wessels Telecom te laten uitvoeren maar dit was helaas door de beperkte ruimte niet mogelijk. Het verkeer kan passeren maar houd u rekening met een langere reistijd en uiteraard proberen wij de verkeershinder tot een minimum te beperken. Heeft u nog vragen? Op werkdagen kunt u tussen 8.00 en 16.30 uur contact opnemen met de heer T. Bosch van Vitens via 06 51 08 24 47. Officiële bekendmakingen en mededelingen De officiële bekendmakingen en mededelingen zijn een publicatie van de gemeente De Ronde Venen. In deze rubriek staan officiële bekendmakingen en mededelingen die voor u van belang kunnen zijn. -

Utrecht, the Netherlands

city document Utrecht, The Netherlands traffic, transport and the bicycle in Utrecht URB-AL R8-P10-01 'Integration of bicycles in the traffic enginering of Latin American and European medium sized cities. An interactive program for education and distribution of knowledge' European Commission EuropeAid Co-operation Office A study of the city of Utrecht, the Netherlands The tower of the Dom church and the Oudegracht canal form the medieval heart of Utrecht. 1 Introduction 1.1 General characteristics of the city Utrecht is, after Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, the fourth largest city in the Netherlands, with a population of approximately 258,000. Utrecht is the capital city of the province of Utrecht. The city lies in the heart of the Netherlands, at an intersection of roads, railways and waterways. The city is very old: it was founded by the Romans in around 47 AD. The city was at that time situated on the Rhine, which formed the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. The city is located in flat country, surrounded by satellite towns with grassland to the west and forested areas to the east. Utrecht forms part of “Randstad Holland”, the conurbation in the west of the Netherlands that is formed by the four large cities of the Netherlands and their satellite towns. Symbols for old Utrecht: Dom church and the Oudegracht canal. 1 The Netherlands is densely populated, with a total population of around 16 million. The population density is 457 inhabitants per km2. A closely-knit network of motorways and railways connects the most important cities and regions in the Netherlands. -

Vernieuwing Regionale Tramlijn 2020

VERNIEUWING REGIONALE TRAMLIJN 2020 Overvecht Reizigers in de regio Utrecht kunnen vanaf het tweede kwartaal 2021 zonder overstap vanuit Tuindorp Nieuwegein en IJsselstein doorreizen in de nieuwe trams en over vernieuwd spoor naar Utrecht Science Park Tweede Daalsebuurt Wittevrouwen (De Uithof). Vanaf dat moment is er één doorgaande verbinding met nieuwe trams over het gehele traject. Tracé X UTRECHT Rijnsweerd Noord P+R De Uithof Utrecht Centraal Utrecht Centraal Jaarbeursplein Centrumzijde De Uithof WKZ Graadt van Roggenweg Oog in Al Padualaan UMCU Utrecht Centraal Nieuwe trams, nieuwe trambaan, aangepaste haltes en een nieuwe verbinding Kromme Rijn Heidelberglaan Vaartsche Rijn 24 Oktober Galgenwaard plein-Zuid Dichterswijk 5 Meiplein Tracé Z De tramlijn in Utrecht, Nieuwegein en IJsselstein is na ruim dertig jaar gebruik aan vervanging toe. Om onze reizigers Rivierenwijk Papendorp Vasco da Tracé A een veilige en comfortabele reis te blijven bieden, vernieuwen we de tramlijn. We hebben daarom nieuwe trams Gamalaan Kanalen- besteld met meer zitplaatsen en meer comfort. Alle perrons van de haltes tussen Utrecht Centraal Jaarbeursplein en eiland Zuid Lunetten P+R Westraven Nieuwegein-Zuid en IJsselstein-Zuid worden verlaagd (0,5 meter) en verlengd (15 meter). Dit is nodig om de perrons Remise passend te maken voor de nieuwe trams. Verder vernieuwen we het tramsysteem dat zorgt voor de aansturing van de Zuilenstein Amsterdam - Rijnkanaal seinen en wissels. Ook vernieuwen we delen van de trambaan in Nieuwegein-Zuid en IJsselstein. Ten slotte testen we de Batau Noord opgebouwde haltes, nieuwe trams en nieuwe systemen. Dit werk wordt uitgevoerd door BAM Infra Rail bv in opdracht Tracé B Wijkersloot van het trambedrijf van de provincie Utrecht. -

Woonvisie 2013-2020

Woonvisie 2013-2020 Definitieve versie Inhoudsopgave Inhoud 0. Samenvatting 7 1. Inleiding 9 1.1 Aanleiding 9 1.2 Leeswijzer 10 2. Bestuurlijke ambities 11 3. Beleidskeuzes 15 4. De Biltse situatie 20 4.1 De Biltse samenleving 20 4.1.1 Demografische ontwikkelingen 20 4.1.2 Economische ontwikkelingen 21 4.2 De Biltse woningmarkt 21 4.2.1 De Bilt in de regio 21 4.2.2 Huidige woningvoorraad 21 4.2.3 Lokale en regionale woningbehoeften 22 5. Sturingsinstrumenten 24 5.1 Nieuwbouw 24 5.1.1 Woningaanbod afstemmen op de vraag 24 5.1.2 Woningen specifiek labelen voor doelgroepen 24 5.1.3 Haalbaarheid starterslening onderzoeken 25 5.1.4 Koop- goedkoop constructie inzetten 26 5.1.5 Haalbaarheid en animo onderzoeken voor woon- werkpanden in De Bilt. 26 5.1.6 Collectief particulier opdrachtgeverschap stimuleren 27 5.1.7 Doorstroming stimuleren 27 5.1.8 Levensloopbestendig en duurzaam bouwen 27 5.2 Bestaande bouw 28 5.2.1 Mensen met een zorgvraag langer zelfstandig thuis laten wonen 28 5.2.2 Levensloop bestendige aanpassingen aan de woning stimuleren 28 5.2.3 Onderzoek naar levensloopbestendige woonwijken 29 5.2.4 Doorstroming stimuleren 29 5.2.5 Doorzon scan uitvoeren 30 5.2.6 Verduurzamen bestaande woningvoorraad 30 5.3 Sturingsmatrix 31 6. Samenwerken met partners 33 6.1 Samenwerkende partners 33 6.2 Rollen en verantwoordelijkheden van partners 34 6.3 Prestatieafspraken corporatie 35 7. Evaluatie en actualisatie Woonvisie 2013-2020 36 4 GEMEENTE DE BILT, WOONVISIE 2012-2020 Bijlagen 37 Bijlage 1 Evaluatie Woonvisie 2006-2015 39 Bijlage 2 Beleidskaders 52 Bijlage 3 De Biltse situatie 60 Bijlage 4 Indicatief woningbouwprogramma 68 Bijlage 5 Woningbouwprogramma 2013- 2020 70 5 GEMEENTE DE BILT, WOONVISIE 2012-2020 0. -

Living with Rivers Netherland Plain Polder Farmers' Migration to and Through the River Flatlands of the States of New York and New Jersey Part I

Living with Rivers Netherland Plain Polder Farmers' Migration to and through the River Flatlands of the states of New York and New Jersey Part I 1 Foreword Esopus, Kinderhook, Mahwah, the summer of 2013 showed my wife and me US farms linked to 1700s. The key? The founding dates of the Dutch Reformed Churches. We followed the trail of the descendants of the farmers from the Netherlands plain. An exci- ting entrance into a world of historic heritage with a distinct Dutch flavor followed, not mentioned in the tourist brochures. Could I replicate this experience in the Netherlands by setting out an itinerary along the family names mentioned in the early documents in New Netherlands? This particular key opened a door to the iconic world of rectangular plots cultivated a thousand year ago. The trail led to the first stone farms laid out in ribbons along canals and dikes, as they started to be built around the turn of the 15th to the 16th century. The old villages mostly on higher grounds, on cross roads, the oldest churches. As a sideline in a bit of fieldwork around the émigré villages, family names literally fell into place like Koeymans and van de Water in Schoonrewoerd or Cool in Vianen, or ten Eyck in Huinen. Some place names also fell into place, like Bern or Kortgericht, not Swiss, not Belgian, but Dutch situated in the Netherlands plain. The plain part of a centuries old network, as landscaped in the historic bishopric of Utrecht, where Gelder Valley polder villages like Huinen, Hell, Voorthuizen and Wekerom were part of. -

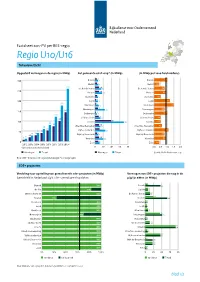

Factsheet Zon-PV U10-U16 PDF Document

Factsheet zon-PV per RES-regio Regio U10/U16 Totaaloverzicht Opgesteld vermogen in de regio (in MWp) Per gemeente eind 2019* (in MWp) (In MWp per 1000 huishoudens) 4 Bunnik 7 Bunnik 1,0 5 De Bilt 8 De Bilt 0,4 258 10 De Ronde Venen 15 De Ronde Venen 0,8 10 Houten 17 Houten 0,9 5 IJsselstein 7 IJsselstein 0,5 3 Lopik 7 Lopik 1,2 176 3 Montfoort 9 Montfoort 1,5 7 Nieuwegein 24 Nieuwegein 0,8 142 Oudewater 2 Oudewater 1,0 120 5 Stichtse Vecht 9 Stichtse Vecht 0,5 100 13 Utrecht 39 Utrecht 0,5 80 70 74 10 0,6 60 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 13 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 53 11 Vijeerenlanden 25 Vijeerenlanden 1,1 41 41 28 29 5 0,8 20 Wijk bij Duurstede 8 Wijk bij Duurstede 8 12 10 Woerden 20 Woerden 0,9 8 Zeist 11 Zeist 0,4 * *(per einde van het kalenderjaar) , , , , , Woningen Totaal Woningen Totaal Gemiddeld in Nederland: 0,9 Bron: CBS – Zonnestroom: opgesteld vermogen *voorlopige cijfers SDE+ projecten Verdeling naar opstelling van gerealiseerde sde+ projecten (in MWp) Vermogen van SDE+ projecten die nog in de Gemiddeld in Nederland: 63% SDE+ gerealiseerd op daken pijplijn zitten (in MWp) 6 Bunnik 100% Bunnik 37 7 De Bilt 83% De Bilt 7 12 De Ronde Venen 100% De Ronde Venen 12 20 Houten 24% Houten 54 3 IJsselstein 100% IJsselstein 3 4 Lopik 100% Lopik 4 7 Montfoort 100% Montfoort 7 36 Nieuwegein 70% Nieuwegein 41 3 Oudewater 100% Oudewater 3 11 Stichtse Vecht 100% Stichtse Vecht 11 74 Utrecht 100% Utrecht 74 5 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 100% Utrechtse Heuvelrug 6 37 Vijeerenlanden 100% Vijeerenlanden 37 3 Wijk bij Duurstede 100% Wijk bij Duurstede -

National Reform Programme 2020 the Netherlands

National Reform Programme 2020 The Netherlands 1 Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 1.1. European Semester ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2. Structure of the document .................................................................................................... 3 1.3. Country Report The Netherlands 2020 ............................................................................... 4 2. Macroeconomic context .................................................................................. 6 3. Country-specific recommendations ................................................................. 7 3.1. First recommendation for the Netherlands ........................................................................ 7 3.2. Second recommendation for the Netherlands ................................................................ 13 3.3. Third recommendation for the Netherlands .................................................................... 19 3.4. Relationship with recommendations for the euro area ................................................. 27 3.5. Investment strategy in the context of cohesion policy ................................................. 29 4. Progress on the Europe 2020 strategy and the Sustainable Development Goals ........................................................................................................................