Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: Interim Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Britain Further Heathrow’S Plan for Connecting the UK to Growth

VOLUME 1 Taking Britain further Heathrow’s plan for connecting the UK to growth #BritainsHeathrow Disclaimer This document has been prepared by Heathrow Airport Limited solely in response to an invitation from the Airports Commission. It should not be used for any other purpose or in any other context and Heathrow Airport Limited accepts no responsibility for its use in that regard Contents Volume 1 - Technical submission Contents ........................................................................................................................ 3 Foreword ....................................................................................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 11 Connecting for growth ................................................................................................................... 12 Listening to what our stakeholders say ........................................................................................... 18 Our vision for a world-class hub airport ........................................................................................... 20 Connecting all of the UK ................................................................................................................ 24 Building a sustainable Heathrow ..................................................................................................... 29 The deliverable solution ................................................................................................................. -

South West Herts Economy Study

South West Hertfordshire Economic Study A Final Report by Regeneris Consulting and GL Hearn South West Hertfordshire Councils South West Hertfordshire Economic Study February 2016 Regeneris Consulting Ltd www.regeneris.co.uk South West Hertfordshire Economic Study Contents Page Executive Summary i Purpose of the Study and Approach i Functional Economic Market Area (FEMA) i Policy Context ii Economic Baseline ii Market Assessment iii Growth Scenarios iv 1. Introduction and Purpose of Study 1 2. Defining the Functional Economic Area 4 Housing Market Area 6 Local Enterprise Partnership Geographies 9 Flow of Goods, Services and Information 13 Service Market for Consumers 16 Cultural and Social Well-Being Catchments 19 Transport Network 21 Future Considerations 22 The FEMA of South West Herts 24 3. Policy Context 27 4. The South West Herts Economy: An Overview 37 Size of the South West Herts Economy 37 Geography of the South-West Hertfordshire Economy 39 Recent Economic Performance 41 Labour Market 44 Broad Sectoral Composition 46 Sector Strengths 49 Structure of Business Base 57 Enterprise 60 5. Commercial Property Market Assessment 63 South West Hertfordshire Economic Study National Economic Conditions 63 Office Market Review 63 Industrial Sector Review 71 Commercial Agents Consultations 76 Summary 78 6. Future Growth Scenarios 80 Higher Growth Scenario 102 Conclusions on Preferred Scenario 108 7. Relationship with London 111 Introduction 111 Migration 112 8. Supply of Employment Land 120 Introduction 120 Site Assessment Methodology 120 Sites in Dacorum 122 Sites in Hertsmere 124 Sites in St Albans 141 Sites in Three Rivers 145 Sites in Watford 151 Conclusion 158 9. -

The Public Health Impact of the Buncefield Oil Depot Fire the Public Health Impact of the Buncefield Oil Depot Fire

The Public Health Impact of the Buncefield Oil Depot Fire The Public Health Impact of the Buncefield Oil Depot Fire Report prepared by the Chief Executive’s Office, Health Protection Agency in collaboration with the Dacorum and Watford and Three Rivers Primary Care Trusts. Prof. Pat Troop Chief Executive, Health Protection Agency With thanks to The Buncefield Health Surveillance Steering Group and Tina Endericks, Health Protection Agency, for co-ordinating and editing this report. Please direct any queries concerning this report to: [email protected] This report is available at: www.hpa.org.uk www.watford3r-pct.nhs.uk www.dacorum-pct.nhs.uk ISBN: 0 901144 82 7 PAGES_01_TO_15 14/7/06 00:03 Page 1 T HE P UBLIC H EALTH I MPACT OF THE B UNCEFIELD O IL D EPOT F IRE - 2006 Appendix 1 Contents Chief Executive’s Foreword 3 Executive Summary 4 Summary of the Buncefield Oil Depot Fire 6 Assessing the Public Health Impact 8 Key Findings 10 Appendices 1 Environmental Impacts of the 17 Buncefield Oil Depot Explosion 2 Study of Accident and Emergency Attendances 51 in Hemel Hempstead and Watford 3 Buncefield Follow up Population Survey 71 4 Atmospheric Modelling and Monitoring 89 1 PAGES_01_TO_15 14/7/06 00:03 Page 2 T HE P UBLIC H EALTH I MPACT OF THE B UNCEFIELD O IL D EPOT F IRE - 2006 2 PAGES_01_TO_15 14/7/06 00:03 Page 3 T HE P UBLIC H EALTH I MPACT OF THE B UNCEFIELD O IL D EPOT F IRE - 2006 Chief Executive’s Foreword This report is important as it is the first time this type of public health follow-up study has been undertaken and reported following a major environmental incident in the UK. -

New Dimension— Enhancing the Fire and Rescue Services' Capacity to Respond to Terrorist and Other Large-Scale Incidents

House of Commons Public Accounts Committee New Dimension— Enhancing the Fire and Rescue Services' capacity to respond to terrorist and other large-scale incidents Tenth Report of Session 2008–09 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 February 2009 HC 249 [Incorporating HC 1184–i, Session 2007–08] Published on 12 March 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Public Accounts Committee The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine “the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit” (Standing Order No 148). Current membership Mr Edward Leigh MP (Conservative, Gainsborough) (Chairman) Mr Richard Bacon MP (Conservative, South Norfolk) Angela Browning MP (Conservative, Tiverton and Honiton) Mr Paul Burstow MP (Liberal Democrat, Sutton and Cheam) Mr Douglas Carswell MP (Conservative, Harwich) Rt Hon David Curry MP (Conservative, Skipton and Ripon) Mr Ian Davidson MP (Labour, Glasgow South West) Angela Eagle MP (Labour, Wallasey) Nigel Griffiths MP (Labour, Edinburgh South) Rt Hon Keith Hill MP (Labour, Streatham) Mr Austin Mitchell MP (Labour, Great Grimsby) Dr John Pugh MP (Liberal Democrat, Southport) Geraldine Smith MP (Labour, Morecombe and Lunesdale) Rt Hon Don Touhig MP (Labour, Islwyn) Rt Hon Alan Williams MP (Labour, Swansea West) Phil Wilson MP (Labour, Sedgefield) The following member was also a member of the committee during the parliament. Mr Philip Dunne MP (Conservative, Ludlow) Powers Powers of the Committee of Public Accounts are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 148. -

Buncefield Major Incident Investigation

BUNCEFIELD MAJOR INCIDENT INVESTIGATION Initial Report to the Health and Safety Commission and the Environment Agency of the investigation into the explosions and fires at the Buncefield oil storage and transfer depot, Hemel Hempstead, on 11 December 2005 Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board a b BUNCEFIELD MAJOR INCIDENT INVESTIGATION Initial Report to the Health and Safety Commission and the Environment Agency of the investigation into the explosions and fires at the Buncefield oil storage and transfer depot, Hemel Hempstead, on 11 December 2005 Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board i ii Contents Executive summary iv Introduction 1 Part 1 – Summary of the incident and subsequent Investigation 5 M Overview of Buncefield operations 5 M Timeline of key events 7 M Emergency response to the Buncefield incident 10 M The Investigation 11 Part 2 – Issues of concern arising from the Investigation to date 18 M Design and operation of storage sites 18 M Emergency response to incidents 21 M Advice to planning authorities 23 Annexes 1 Terms of reference and progress 24 2 Members of the independent Board 27 3 Planning history of Buncefield site and neighbouring developments 28 4 UK petroleum refinery, pipeline and storage system 35 5 Incidents that have similarities with the Buncefield incident 37 6 Fire and explosion hazards from petrol 39 7 Product composition at Buncefield 44 8 Regulatory framework for high hazard sites 46 9 Regulation of perfluorooctane sulphonates (PFOS) 49 10 Legal considerations 51 Glossary 54 Further information 58 iii iv Executive summary The terms of reference of the Investigation directed by the Health and Safety Commission into the explosions and fires at the Buncefield oil storage and transfer depot, Hemel Hempstead, on 11 December 2005 require an initial report to be produced for the Health and Safety Commission and the Environment Agency when the main facts of the incident have been established. -

Recommendations on the Emergency Preparedness For, Response to and Recovery from Incidents

Recommendations on the emergency preparedness for, response to and recovery from incidents Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board a Recommendations on the emergency preparedness for, response to and recovery from incidents Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board © Crown copyright This publication may be freely reproduced, except for advertising, endorsement or commercial purposes. First published 07/07. Photographs 1-4, 7, 8, 10 and 11 courtesy of Hertfordshire County Council Photograph 5 courtesy of the Fire Service College Photographs 6 and 9 courtesy of the Press Association Photograph 12 by Brian Howard, supplied by Hemel Hempstead Local History ii and Museum Society and the Dacorum Heritage Trust Limited Contents Introduction 1 The Board’s approach Scope of the recommendations Status of the recommendations The recommendations Assessing the potential for a major incident 7 Recommendation 1 Managing a major incident on site 8 Recommendations 2–9 Preparing for and responding to a major incident off site 13 Recommendations 10–26 Recovering from a major incident 27 Recommendations 27–32 Annexes 1: Terms of reference and progress 32 2: Members of the independent board 35 3: Devolved and equivalent administrations 36 4: Other major incidents causing extensive off-site damage 39 5: National Recovery Working Group terms of reference 41 References 45 Glossary 48 Further information 51 iii Figure 1 An overview of the Buncefield site and adjacent business and residential communities before the incident iv Introduction 1 This report sets out recommendations to improve both planning for emergencies and the effectiveness of the response to emergencies at Buncefield-like sites and other high-hazard industrial facilities regulated under the COMAH1 regime. -

Buncefield Report

BUNCEFIELD MAJOR INCIDENT INVESTIGATION Initial Report to the Health and Safety Commission and the Environment Agency of the investigation into the explosions and fires at the Buncefield oil storage and transfer depot, Hemel Hempstead, on 11 December 2005 Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board a b BUNCEFIELD MAJOR INCIDENT INVESTIGATION Initial Report to the Health and Safety Commission and the Environment Agency of the investigation into the explosions and fires at the Buncefield oil storage and transfer depot, Hemel Hempstead, on 11 December 2005 Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board i ii Contents Executive summary iv Introduction 1 Part 1 – Summary of the incident and subsequent Investigation 5 M Overview of Buncefield operations 5 M Timeline of key events 7 M Emergency response to the Buncefield incident 10 M The Investigation 11 Part 2 – Issues of concern arising from the Investigation to date 18 M Design and operation of storage sites 18 M Emergency response to incidents 21 M Advice to planning authorities 23 Annexes 1 Terms of reference and progress 24 2 Members of the independent Board 27 3 Planning history of Buncefield site and neighbouring developments 28 4 UK petroleum refinery, pipeline and storage system 35 5 Incidents that have similarities with the Buncefield incident 37 6 Fire and explosion hazards from petrol 39 7 Product composition at Buncefield 44 8 Regulatory framework for high hazard sites 46 9 Regulation of perfluorooctane sulphonates (PFOS) 49 10 Legal considerations 51 Glossary 54 Further information 58 iii iv Executive summary The terms of reference of the Investigation directed by the Health and Safety Commission into the explosions and fires at the Buncefield oil storage and transfer depot, Hemel Hempstead, on 11 December 2005 require an initial report to be produced for the Health and Safety Commission and the Environment Agency when the main facts of the incident have been established. -

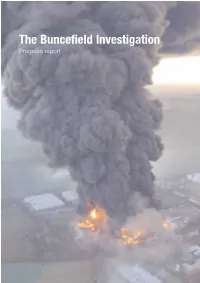

The Buncefield Investigation Progress Report the Buncefield Investigation

The Buncefield Investigation Progress report The Buncefield Investigation Contents Foreword 3 Part 1 The Investigation so far 4 1.1 The incident 4 1.2 What is known about the explosions and fire 9 1.3 The continuing Investigation 12 1.4 Review of HSE/EA roles in regulating activities at Buncefield 14 1.5 Major Incident Investigation Board 15 Part 2 Background 16 2.1 Site description 16 2.2 Regulation of high-hazard sites 19 Annexes 1 Background to the COMAH Regulations 21 2 HSE’s current approach to land use planning 22 3 Investigation terms of reference 25 4 Major Incident Investigation organogram 26 5 Further information 27 Glossary 28 Photographs are courtesy of the Chiltern Air Support Unit and Hertfordshire County Council 2 The Buncefield Investigation Foreword At the first meeting of the Major Incident Investigation Board (MIIB) on 24 January I was asked to prepare, for the second (10 February) meeting, a progress report on the Buncefield Major Incident Investigation by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and the Environment Agency (EA). This was to bring together relevant background material and to cover progress with the investigation and such facts as have been established to this point. The MIIB said that this progress report would not constitute the ‘initial report’ required by Terms of Reference 6, since some of the main facts have yet to be established. This progress report is a stepping stone towards the initial report. The report describes the incident and the nature of the site and surrounding communities and the initial responses by EA and HSE. -

Air Quality in London

Air quality in London London Air Quality Network Report 13 2005-6 IMAGE: FRANCISBOOTH.COM IMAGE: Main contact London Air Quality Network Environmental Research Group King’s College London 4th Floor Franklin-Wilkins Building 150 Stamford Street London SE1 9NH 020 7848 4019 [email protected] Credits Written by Gary Fuller and Louise Meston Cover image (bottom) by francisbooth.com Designed by the Corporate Design Unit King’s College London [email protected] © King’s College London February 2008 Introduction Contents The measurements detailed in this report result from a 2 team effort, undertaken by staff who are dedicated and Foreword committed to their work. 4 The Environmental Research Group Summary 5 Director of the Environmental Emissions Introduction Research Group Joanne Best Professor Frank Kelly Stephen Hedley* 6 Stephen Inch Air quality measurements Air quality monitoring Jon Alexander Finance Timothy Baker Maria Lavender* 8 Ben Barratt Air quality during 2005 Hima Chouhan Computing Gary Fuller* Robert Hepburn* 6 David Green Sam Hope-Evans The Buncefield oil depot fire Andrew Grieve Olufemi Kilani Paul Johnson Ian Troughton Daniel Marsh 20 Louise Meston Administration Relative results 1996 to 2006 Ellie Norris Adina Beck Karin Nilsdotter Valentina Lotti* 24 Max Priestman Wendy Rowlands Progress towards the attainment Ana Rowan of AQS objectives Anja Tremper Air quality modelling 27 Sean Beevers* References David Dajnak Stephen Hedley 29 Nutthida Kitwiroon Appendix 1: LAQN monitoring sites Hrishi Mittal Cathryn Tonne *Suggested first point of contact 33 Emily Westmoreland within each team. Appendix 2: Network changes during 2005 38 Appendix 3: Detailed results Inside back cover Appendix 4: Air quality strategy objectives www.londonair.org.uk Foreword Professor Frank Kelly, Director of the Environmental Research Group (ERG) elcome to the thirteenth annual report of 2006 and the more recent addition of 3D visualisation the London Air Quality Network (LAQN). -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 583 3 July 2014 No. 18 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 3 July 2014 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1057 3 JULY 2014 1058 Tracey Crouch (Chatham and Aylesford) (Con): The House of Commons Secretary of State will be aware that alongside the national lottery, society lotteries contributed £145 million Thursday 3 July 2014 to good causes in 2012-13 and could provide a lot more if the prizes, draw and turnover rules were deregulated. The House met at half-past Nine o’clock His Department has long promised a consultation on this but has yet to publish it. In the light of the recent PRAYERS Centre for Economics and Business Research report on society lotteries, can he tell the House when the consultation might come? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Sajid Javid: Changes in lottery and gambling markets have made it clear to us that the consultation on society Oral Answers to Questions lotteries should be more wide ranging than we had previously thought. The Gambling Commission is providing us with further information and advice, and we are CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT planning to conduct the consultation later this year. The Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport Helen Goodman (Bishop Auckland) (Lab): The Arts was asked— Council announced this week that 99 organisations will National Lottery Funding be financed solely by the national lottery and it has to cut support to 58 other arts organisations because of 1. -

Central Herts Employment Land Review Interim Report Nov 06

Hertsmere, St. Albans and Welwyn Hatfield Councils CENTRAL HERTFORDSHIRHERTFORDSHIREE EMPLOYMENT LAND REREVIEWVIEW Interim Report November 2006 ROGER TYM & PARTNERS Fairfax House 15 Fulwood Place London WC1V 6HU t (020) 7831 2711 f (020) 7831 7653 e [email protected] w www.tymconsult.com This document is forformattedmatted for doubledouble----sidedsided printingprinting. P1650 CONTENTS 111 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... ................................................................................................ ............................................. 111 The Study Brief........................................................................................................1 This Interim Report..................................................................................................2 222 POLICY CONTEXTCONTEXT................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ....................................... 555 National Policy.........................................................................................................5 Strategic Planning Policy.........................................................................................6 Local Plans..............................................................................................................9 Economic Development Strategies........................................................................12 -

Buncefield Fire

Swiss Fire Brigade Association December 11, 2005 Buncefield Fire Quick Look Report bürkel baumann schuler Swiss Fire Brigade Association December 11th, 2005 Buncefield Fire Quick Look Report A major fire occurred on 11th December 2005 in a storage tank depot 40 km north-west of London. After being triggered by a powerful explosion, numerous tanks in which heating fuels and engine fuels were stored burned for several days. The fire is being described as the largest fire incident in Europe since the Second World War. The present assessment of in- formation relating to the major fire in the Buncefield storage tank depot was produced shortly after the incident. It is based on enquiries addressed to specialists and an examination of official information and press reports. Because of the uniqueness of the event and the copious visual image and press material, a briefly worded and quickly available assessment of this information is of great interest to the emergency services. The present Quick Look Report contains selected photographs and graphics. The visual in- formation is supplemented by a description of the incident with comments and interpretations together with quotations from the press. Winterthur, 30th December 2005 Bürkel Baumann Schuler Engineers + Planners AG Gertrudstrasse 17 CH-8400 Winterthur Switzerland Tel.: +41 52 260 07 10 Fax: +41 52 260 07 20 Mail [email protected] 1 Swiss Fire Brigade Association Contents Contents Abbreviations 3 Conversions 3 1 Site of the incident 4 1.1 Overview 4 1.2 The storage tank depot 6 2 Explosion