74 the Sequence in the Ceramic Tradition of El

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHRONOLOGY of the RÍO BEC SETTLEMENT and ARCHITECTURE Eric Taladoire, Sara Dzul, Philippe Nondédéo, Mélanie Forné

CHRONOLOGY OF THE RÍO BEC SETTLEMENT AND ARCHITECTURE Eric Taladoire, Sara Dzul, Philippe Nondédéo, Mélanie Forné To cite this version: Eric Taladoire, Sara Dzul, Philippe Nondédéo, Mélanie Forné. CHRONOLOGY OF THE RÍO BEC SETTLEMENT AND ARCHITECTURE. Ancient Mesoamerica, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2013, 24 (02), pp.353-372. 10.1017/S0956536113000254. hal-01851495 HAL Id: hal-01851495 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01851495 Submitted on 30 Jul 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ancient Mesoamerica, 24 (2013), 353–372 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2014 doi:10.1017/S0956536113000254 CHRONOLOGY OF THE RÍO BEC SETTLEMENT AND ARCHITECTURE Eric Taladoire,a Sara Dzul,b Philippe Nondédéo,a and Mélanie Fornéc aCNRS-Université de Paris Panthéon-Sorbonne, UMR 8096 Archéologie des Amériques, 21 allée de l’Université, F-92023, Nanterre Cedex, France bCentro Regional INAH, Yucatan, Antigua Carretera a Progreso s/n, km 6.5, prolongación Montejo. Col. Gonzalo Guerrero, C.P. 97310. Mérida, Yucatán cPost-doctoral researcher, Cancuen Project, CEMCA-Antenne Amérique Centrale Ambassade de France 5 Av. 8-59 Zone 14, Guatemala C-A Abstract Chronology is a crucial issue given the specific settlement patterns of the Río Bec region located on the northern fringe of the Maya central lowlands. -

Lunes Salón 1 Síntesis Y Arqueología Regional

LUNES SALÓN 1 08:30-09:30 INSCRIPCIÓN 09:30-10:00 INAUGURACIÓN 10:00-10:30 RECESO CAFÉ SÍNTESIS Y ARQUEOLOGÍA REGIONAL 10:30-11:00 ATLAS ARQUEOLÓGICO DE GUATEMALA, UN PROGRAMA DE REGISTRO NACIONAL. RESULTADOS DE 25 AÑOS DE TRABAJO Lilian A. Corzo 11:00-11:30 LA ARQUITECTURA DEL SURESTE DE PETÉN, ANÀLISIS DE 25 AÑOS DE INVESTIGACIONES ARQUEOLÓGICAS EN UNA REGIÓN POCO CONOCIDA Jorge Chocón 11:30-12:00 NAKUM Y SU IMPORTANCIA EN LA HISTORIA DE LAS TIERRAS BAJAS MAYAS: RESULTADOS DE LOS TRABAJOS ARQUEOLÓGICOS REALIZADOS ENTRE 2006- 2010 Jaroslaw Źralka, Wieslaw Koszul, Bernard Hermes, Katarzyna Radnicka, Juan Luis Velásquez. 12:00-12:30 EL NORESTE DE PETÉN, GUATEMALA Y EL NOROESTE DE BELICE, REGIÓN CULTURAL QUE TRASCIENDE FRONTERAS Liwy Grazioso Sierra y Fred Valdez Jr. 12:30-01:00 RESULTADOS REGIONALES DEL PROYECTO NACIONAL TIKAL: ENFOQUE EN EL PROYECTO TRIÁNGULO Oscar Quintana Samayoa 01:00-01:30 RECONSTITUCIONES IDEALES DEL GRUPO 6C-XVI DE TIKAL (in memoriam) Paulino Morales y Juan Pedro Laporte 01:30-03:00 RECESO ALMUERZO 03:00-03:30 EL PATRIMONIO MUNDIAL DE GUATEMALA EN EL CONTEXTO DEL ÁREA MAYA Erick Ponciano y Juan Carlos Melendez 03:30-04:00 NUEVOS DATOS PARA LA HISTORIA DE TIKAL Oswaldo Gómez 04:00-04:30 CAMINANDO BAJO LA SELVA: PATRÓN DE ASENTAMIENTO EN LA CUENCA MIRADOR Héctor Mejía 04:30-05:00 RECESO CAFÉ 2 05:00-05:30 DIEZ AÑOS DE INVESTIGACIONES REGIONALES EN LA ZONA ARQUEOLÓGICA DE HOLMUL, PETÉN Francisco Estrada Belli 05:30-06:00 25 AÑOS DE PROYECTOS REGIONALES EN EL VALLE DEL RÍO LA PASIÓN: VISTA GENERAL DE LAS INVESTIGACIONES, RESULTADOS Y PERSPECTIVAS SOBRE LOS ÚLTIMOS SIGLOS DE UNA GRAN RUTA MAYA Arthur Demarest, Juan Antonio Vadés, Héctor Escobedo, Federico Fahsen, Tomás Barrientos, Horacio Martínez 06:00-06:30 PERSPECTIVAS SOBRE EL CENTRO-OESTE DE PETÉN DESDE LA JOYANCA, ZAPOTE BOBAL Y OTROS CENTROS MAYAS CLÁSICOS, GUATEMALA Edy Barrios, M. -

Terminal Classic Occupation in the Maya Sites Located in the Area of Triangulo Park, Peten, Guatemala

Prace Archeologiczne No. 62 Monographs Jarosław Źrałka Terminal Classic Occupation in the Maya Sites Located in the Area of Triangulo Park, Peten, Guatemala Jagiellonian University Press Kraków 2008 For Alicja and Elżbieta CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER I: Introduction .................................................................................. 11 CHAPTER II: Triangulo Park – defi nition, geographical environment, history and methodology of research ............................................................. 19 CHAPTER III: Analysis of Terminal Classic occupation in the area of Triangulo Park ............................................................................................. 27 – Nakum ............................................................................................................ 27 – Naranjo ........................................................................................................... 135 – Yaxha .............................................................................................................. 146 – Minor sites ...................................................................................................... 175 – Intersite areas .................................................................................................. 187 CHAPTER IV: Summary and conclusions ......................................................... 191 – The Terminal Classic period in the Southern Maya Lowlands: an -

Title Page, Table of Contents, and Foreword

Millenary Maya Societies: Past Crises and Resilience Sociedades mayas milenarias: crisis del pasado y resiliencia Papers from the International Colloquium (Memorias del coloquio international) “Sociétés mayas millénaires: crises du passé et résilience,” Musée du quai Branly Paris, July 1-2, 2011 Edited by (editado por) M.-Charlotte Arnauld Alain Breton © 2013 Mesoweb CONTENTS / CONTENIDO 0 - Foreword / Prólogo 5 Marie-Charlotte Arnauld et al. INAUGURAL LECTURE / CONFERENCIA INAUGURAL 1 - Time, Memory, and Resilience among the Maya 10 Prudence M. Rice PART I / PARTE I CRISES AND RUPTURES / CRISIS Y RUPTURAS 2 - The Collapse of the Classic Maya Kingdoms of the Southwestern Petén: Implications for the End of Classic Maya Civilization 22 Arthur A. Demarest 3 - Crisis y cambios en el Clásico Tardío: los retos económicos de una ciudad entre las Tierras Altas y las Tierras Bajas mayas 49 Mélanie Forné, Chloé Andrieu, Arthur A. Demarest, Paola Torres, Claudia Quintanilla, Ronald L. Bishop y Olaf Jaime-Riverón 4 - The Terminal Classic at Ceibal and in the Maya Lowlands 62 Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan 5 - El abandono de Aguateca, Petén, Guatemala 68 Erick M. Ponciano, Takeshi Inomata y Daniela Triadan 6 - Crisis y superviviencia en Machaquilá, Petén, Guatemala 73 Andrés Ciudad Ruiz, Alfonso Lacadena García-Gallo, Jesús Adánez Pavón y Ma Josefa Iglesias Ponce de León 7 - La crisis de La Blanca en el Clásico Terminal 92 Cristina Vidal Lorenzo y Gaspar Muñoz Cosme 8 - Crecimiento, colapso y retorno ritual en la ciudad antigua de Uaxactún (150 -

Aproximación a La Conservación Arqueológica En Guatemala: La Historia De Un Dilema

86. AP RO X IMACIÓN A LA CON S ERVACIÓN a r qu e o l ó g i c a e n gU a t e m a l a : LA HI S TORIA DE U N DILEMA Erick M. Ponciano XXVIII SIMPO S IO DE IN V E S TIGACIONE S AR QUEOLÓGICA S EN GUATEMALA MU S EO NACIONAL DE AR QUEOLOGÍA Y ETNOLOGÍA 14 AL 18 DE JULIO DE 2014 EDITOR E S Bá r B a r a ar r o y o LUI S MÉNDEZ SALINA S LO R ENA PAIZ REFE R ENCIA : Ponciano, Erick M. 2015 Aproximación a la conservación arqueológica en Guatemala: la historia de un dilema. En XXVIII Simpo- sio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2014 (editado por B. Arroyo, L. Méndez Salinas y L. Paiz), pp. 1053-1064. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala. APROXIM A CIÓN A L A CONSERV A CIÓN A RQUEOLÓGIC A EN GU A TEM A L A : L A HISTORI A DE UN DILEM A Erick M. Ponciano PALABRAS CLAVE Guatemala, recursos culturales, conservación, época prehispánica. ABSTRACT Guatemala has many archaeological sites from pre-colombian times. This characteristic creates a paradoji- cal and complex situation to Guatemala as a society. On one side, there exists a feeling of proud when sites like Tikal, Mirador or Yaxha are mentioned, but on the other side, also exits uncertainty on private lands due to the fear for expropriation from the State when archaeological sites occur in their terrain. Different forms for cultural preservation are presented and how this has developed through time in Guatemala. -

Las Modalidades Y Dinámicas De Las Relaciónes Entre Facciones Políticas En Piedras Negras, Petén, Guatemala : El Dualismo Político Damien Bazy

Las modalidades y dinámicas de las relaciónes entre facciones políticas en Piedras Negras, Petén, Guatemala : el dualismo político Damien Bazy To cite this version: Damien Bazy. Las modalidades y dinámicas de las relaciónes entre facciones políticas en Piedras Negras, Petén, Guatemala : el dualismo político. TRACE (Travaux et recherches dans les Amériques du Centre), Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos (CEMCA) 2011, 59, pp.59-73. halshs- 01885797 HAL Id: halshs-01885797 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01885797 Submitted on 10 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License TRACE 59 (Junio 2011): págs. 59-73 www.cemca.org.mx 5599 Damien Las modalidades y dinámicas de las Bazy relaciones entre facciones políticas en Piedras Negras, Petén, Guatemala El dualismo político Resumen: Retomando los planteamientos de Abstract: Following the lead of several Résumé : À l’instar de nombreux archéolo- varios arqueólogos, intentaremos -

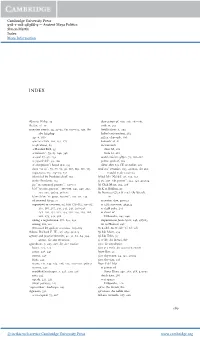

Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48388-9 — Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information INDEX Abrams, Philip, 39 destruction of, 200, 258, 282–283 Acalan, 16–17 exile at, 235 accession events, 24, 32–33, 60, 109–115, 140, See fortifications at, 203 also kingship halted construction, 282 age at, 106 influx of people, 330 ajaw as a verb, 110, 252, 275 kaloomte’ at, 81 as ajk’uhuun, 89 monuments as Banded Bird, 95 Altar M, 282 as kaloomte’, 79, 83, 140, 348 Stela 12, 282 as sajal, 87, 98, 259 mutul emblem glyph, 73, 161–162 as yajawk’ahk’, 93, 100 patron gods of, 162 at a hegemon’s home seat, 253 silent after 810 CE or earlier, 281 chum “to sit”, 79, 87, 89, 99, 106, 109, 111, 113 Ahk’utu’ ceramics, 293, 422n22, See also depictions, 113, 114–115, 132 mould-made ceramics identified by Proskouriakoff, 103 Ahkal Mo’ Nahb I, 96, 130, 132 in the Preclassic, 113 aj atz’aam “salt person”, 342, 343, 425n24 joy “to surround, process”, 110–111 Aj Chak Maax, 205, 206 k’al “to raise, present”, 110–111, 243, 249, 252, Aj K’ax Bahlam, 95 252, 273, 406n4, 418n22 Aj Numsaaj Chan K’inich (Aj Wosal), k’am/ch’am “to grasp, receive”, 110–111, 124 171 of ancestral kings, 77 accession date, 408n23 supervised or overseen, 95, 100, 113–115, 113–115, as 35th successor, 404n24 163, 188, 237, 239, 241, 243, 245–246, as child ruler, 245 248–250, 252, 252, 254, 256–259, 263, 266, as client of 268, 273, 352, 388 Dzibanche, 245–246 taking a regnal name, 111, 193, 252 impersonates Juun Ajaw, 246, 417n15 timing, 112, 112 tie to Holmul, 248 witnessed by gods or ancestors, 163–164 Aj Saakil, See K’ahk’ Ti’ Ch’ich’ Adams, Richard E. -

La Joyanca (Guatemala)

THE RISE AND FALL OF A SECONDARY POLITY: LA JOYANCA (GUATEMALA) M.-Charlotte Arnauld, Eva Lemonnier CNRS, Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Mélanie Forné CEMCA, Guatemala Didier Galop and Jean-Paul Métailié CNRS, Université de Toulouse-Le Mirail Introduction Paleoenvironmental studies have recently made impressive contributions to our understanding of the Maya Lowland Terminal Classic crisis (e.g. Dunning et al. 2012; Hodell et al. 2005; Kennett et al. 2012; Leyden 2002). They put much emphasis on the detection of drought episodes during the ninth century and later. There is no doubt that such events had an impact on Maya sociopolitical dynamics, although ninth-century droughts may have entailed relatively moderate rainfall reduction (Medina- Elizalde et al. 2010, 2012). Not only Maya agriculture but also urban populations were vulnerable to variation in precipitation (Scarborough et al. 2012). However, it is problematic to spatially extrapolate the results of those paleoenvironmental analyses to distant sites across the Lowlands (Aimers and Hodell 2011). Moreover, the impact of reconstructed climatic events does not appear to have been as direct and synchronous as we would expect, and the concatenation of environmental and sociopolitical factors remains poorly investigated (Butzer 2012; see Demarest, this publication). We are now in pressing need of local transdisciplinary studies combining archaeology with paleoenvironmental proxies, allowing interpretations focused on circumscribed, relatively small-scale research “windows.” Arnauld, M.-Charlotte, Eva Lemonnier, Mélanie Forné, Didier Galop, and Jean-Paul Métailié 2013 The Rise and Fall of a Secondary Polity: La Joyanca (Guatemala). In Millenary Maya Societies: Past Crises and Resilience, edited by M.-Charlotte Arnauld and Alain Breton, pp. -

El Cuadrángulo A19 Y Su Relación Con Las Elites De Naranjo, Petén

UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA ÁREA DE ARQUEOLOGÍA El Cuadrángulo A19 y su relación con las elites de Naranjo, Petén. TESIS Presentada por: DANIEL EDUARDO AQUINO LARA Previo a conferírsele el grado académico de LICENCIADO EN ARQUEOLOGÍA Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala, C.A., Abril de 2006 UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS ESCUELA DE HISTORIA AUTORIDADES UNIVERSITARIAS RECTOR: Dr. Luis Alfonso Leal Monterroso SECRETARIO: Dr. Carlos Enrique Mazariegos AUTORIDADES DE LA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA DIRECTOR: Lic. Ricardo Danilo Dardón Flores SECRETARIO: Lic. Oscar Adolfo Haeussler Paredes CONSEJO DIRECTIVO Director: Lic. Ricardo Danilo Dardón Flores Secretario: Lic. Oscar Adolfo Haeussler Paredes Vocal I: Lic. Carlos René García Escobar Vocal II: Licda. Marlen Judith Garnica Vanegas Vocal III: Lic. Julio Galicia Díaz Vocal IV: Est. Marcos Orlando Moreno Hernández Vocal V: Est. Tanya Isabel del Rocío García Monzón COMITÉ DE TESIS Licda. Vilma Fialko Coxemans Lic. Ervin Salvador López Licda. Laura Lucía Gámez A: mis abuelos y mi madre que desde algún sitio del universo guían y protegen mis pasos A: mi padre que día a día estimula mi carrera, recordándome que es mejor dar que recibir A: mis hermanos que me brindan el apoyo en momentos de flaqueza A: mi esposa quien constantemente me inculca la cualidad de perseverar A: todos los verdaderos investigadores que a pesar de la adversidad, continúan hasta alcanzar la meta La presente investigación no hubiese sido posible sin el apoyo de personas e instituciones a quines expreso mi sincero agradecimiento: Al equipo técnico del Proyecto Protección de Sitios Arqueológicos en Petén, por acompañarme en el despertar de mi carrera científica, aportando valiosas ideas y el apoyo más sincero en los momentos difíciles del quehacer arqueológico. -

The Ceramic Sequence of Piedras Negras, Guatemala: Type and Varieties 1

FAMSI © 2004: Arturo René Muñoz The Ceramic Sequence of Piedras Negras, Guatemala: Type and Varieties 1 Research Year : 2003 Culture : Maya Chronology : Classic Location : Northwestern Guatemala Site : Piedras Negras Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Previous Research Current Research The Sample Methods Employed in this Study Piedras Negras Chronology and Typology The Hol Ceramic Phase (500 B.C.–300 B.C.) The Abal Ceramic Phase (300 B.C.–A.D. 175) The Pom Ceramic Phase (A.D. 175–A.D. 350) The Naba Ceramic Phase (A.D. 350–A.D. 560) The Balche Ceramic Phase (A.D. 560–A.D. 620) The Yaxche Ceramic Phase (A.D. 620–A.D. 750) The Chacalhaaz Ceramic Phase (A.D. 750–A.D. 850) The Kumche Ceramic Phase (A.D. 850–A.D. 900?) The Post Classic Type List 1 This report should be taken as a supplement to the "Ceramics at Piedras Negras " report submitted to FAMSI in April of 2002. In most regards, these two reports are complementary. However, it is important to note that the initial report was posted early in the research. In cases where these reports appear contradictory, the data presented here should be taken as correct. Acknowledgements Table of Images Sources Cited Abstract Between March of 2001 and August of 2002, the ceramics excavated from the Classic Maya site Piedras Negras between 1997 and 2000 were subject of an intensive study conducted by the author and assisted by Lic. Mary Jane Acuña and Griselda Pérez of the Universidad de San Carlos in Guatemala City, Guatemala. 2 The primary goal of the analyses was to develop a revised Type:Variety classification of the Piedras Negras ceramics. -

The PARI Journal Vol. XI, No. 1

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume XI, No. 1, Summer 2010 In This Issue: A Hieroglyphic Block from the A Hieroglyphic Region of Hiix Witz, Guatemala Block from the SIMON MARTIN Region of Hiix Witz, University of Pennsylvania Museum Guatemala DORIE REENTS-BUDET by Smithsonian Institution Simon Martin and In recent years, private collectors in process end any possibility of these works Dorie Reents-Budet Guatemala have been registering their entering the international art market, PAGES 1-6 holdings of Precolumbian art with the but it makes them available for scholarly • Registro de Bienes Culturales. This agency, study—thereby enriching both our part of the Instituto de Antropología knowledge of the past and the cultural Palenque from 1560 e Historia (IDAEH), is responsible for patrimony of Guatemala. to 2010 bringing privately held artefacts into the Where Maya objects carry hieroglyphic by official registry of Guatemalan national inscriptions there is the potential of “re- Merle Greene cultural heritage. Not only does this provenancing” them, using mentions of Robertson PAGES 7-16 Joel Skidmore Editor [email protected] Marc Zender Associate Editor [email protected] The PARI Journal 202 Edgewood Avenue San Francisco, CA 94117 415-664-8889 [email protected] Electronic version available at: www.mesoweb.com/ pari/journal/1101 The PARI Journal is made possible by a grant from Precolumbia Mesoweb Press ISSN 1531-5398 Figure 1. The hieroglyphic block registered by IDAEH as No. 1.2.144.915 (photograph by Dorie Reents-Budet). The PARI Journal 11(1):1-6. 1 Martin and Reents-Budet pA pB 1 2 Figure 2. -

Explorations in the Southern Sierra Del Lacandón National Park, Petén, Guatemala

FAMSI © 2005: Andrew K. Scherer Archaeological Reconnaissance at Tixan: Explorations in the Southern Sierra del Lacandón National Park, Petén, Guatemala Research Year : 2005 Culture : Maya Chronology : Classic Location : Petén, Guatemala Site : Tixan, Sierra del Lacandón National Park, Unión Maya Itza, Oso Negro, Cueva de Tres Entradas, La Pasadita, El Túnel, La Técnica, El Kinel Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Methodology Unión Maya Itza Oso Negro Cueva de Tres Entradas La Pasadita El Túnel Tixan La Técnica El Kinel Discussion and Conclusions The Future of the Sierra del Lacandón National Park Personnel of the 2005 Sierra del Lacandón Regional Archaeology Field Team Acknowledgements List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract This report describes the results of three weeks of reconnaissance in the southern portions of the Sierra del Lacandón National Park, Petén, Guatemala. This area is the source of numerous looted monuments that can be attributed to the Classic Maya kingdom of Yaxchilán. These looted monuments include a lintel that was intercepted in 2004 by Guatemalan authorities in the modern community of Retalteco, located near the southern end of the park. Prompted by the recovery of this monument, members of the Sierra del Lacandón Regional Archaeology Project (SLRAP) attempted to visit an area of the park known as Tixan, which is reported to contain vaulted structures and is a possible source of this monument. Three weeks of reconnaissance in the southern portion of the Sierra del Lacandón National Park has provided a more complete understanding of settlement within the Yaxchilán kingdom. Resumen El presente informe describe los resultados de tres semanas de reconocimiento en la parte sur del Parque Nacional Sierra del Lacandón, Petén, Guatemala.