Landscape and History at the Headwaters of the Big Coal River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election Division Presidential Electors Faqs and Roster of Electors, 1816

Election Division Presidential Electors FAQ Q1: How many presidential electors does Indiana have? What determines this number? Indiana currently has 11 presidential electors. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution of the United States provides that each state shall appoint a number of electors equal to the number of Senators or Representatives to which the state is entitled in Congress. Since Indiana has currently has 9 U.S. Representatives and 2 U.S. Senators, the state is entitled to 11 electors. Q2: What are the requirements to serve as a presidential elector in Indiana? The requirements are set forth in the Constitution of the United States. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 provides that "no Senator or Representative, or person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector." Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment also states that "No person shall be... elector of President or Vice-President... who, having previously taken an oath... to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. Congress may be a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability." These requirements are included in state law at Indiana Code 3-8-1-6(b). Q3: How does a person become a candidate to be chosen as a presidential elector in Indiana? Three political parties (Democratic, Libertarian, and Republican) have their presidential and vice- presidential candidates placed on Indiana ballots after their party's national convention. -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

Chap 3 Socio-Eco

City Profile Chapter 3 Socioeconomic enacted legislation forming Raleigh Conditions County from Fayette County and, thus, County government was organized. The An overview and statistical analysis of County was named for Sir Walter Raleigh population and socioeconomic characteris- at the suggestion of General Beckley, and tics of the City of Beckley has been devel- Beckley became the County Seat. As a oped as part of the basis for the Compre- Virginia County, Raleigh County tended hensive Planning process. to politically vote Republican. During the Virginia Secession Convention, at the Historic Roots of outset of the Civil War, Raleigh County was included in the new State of West Beckley Virginia. As the only instance in West The earliest recorded European exploration Virginia history for the territory of a of what is now West Virginia was in 1742 County to be enlarged after its forma- by John Peter Salley. The first explorations tion, the West Virginia Legislature of Raleigh County occurred in 1750 by Dr. approved a political deal to annex the Thomas Walker, and in 1751 by Christo- 168-square mile Slab Fork District and pher Gist of the Ohio Company (a land the rich coal fields of Winding Gulf from investment company). The first known Wyoming County into southwest Raleigh map of the Raleigh County area was County. At the time, this provided a published in London in 1755 based on Democrat majority in Raleigh County these explorations. Two years later, John and a Republican majority in Wyoming James Beckley was born in England, who County. would, in 1795, obtain a grant of 170,038 acres of land in the Raleigh County area, After the construction of the County and, in 1802, be appointed the first Clerk Court House in 1852, some records, of the U.S. -

LEQ: Which President Served in Office for Only One Month?

LEQ: Which President served in office for only one month? William Henry Harrison on his deathbed with Reverend Hawley to Harrison’s left, a niece to Harrison’s right, a nephew to the right of the niece, a physician standing with his arms folded, Secretary of State Daniel Webster with his right hand raised, and Thomas Ewing, Secretary of the Treasury sitting with a handkerchief over his face. Postmaster General Francis Granger is standing by the right door. This image was created by Nathaniel Currier circa 1841. It is titled “Death of Harrison, April 4 A.D. 1841.” This is a later, hand colored version of that image. LEQ: Which President served in office for only one month? William Henry Harrison William Henry Harrison on his deathbed with Reverend Hawley to Harrison’s left, a niece to Harrison’s right, a nephew to the right of the niece, a physician standing with his arms folded, Secretary of State Daniel Webster with his right hand raised, and Thomas Ewing, Secretary of the Treasury sitting with a handkerchief over his face. Postmaster General Francis Granger is standing by the right door. This image was created by Nathaniel Currier circa 1841. It is titled “Death of Harrison, April 4 A.D. 1841.” This is a later, hand colored version of that image. The Age of Jackson Ends Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) was said to have physically suffered at one time or another from the following: chronic headaches, abdominal pains, and a cough caused by a musket ball in his lung that was never removed. -

08 Wv History Reader Fain.Pdf

Early Black Migration and the Post-emancipation Black Community in Cabell County,West Virginia, 1865-1871 Cicero Fain ABSTRACT West Virginia’s formation divided many groups within the new state. Grievances born of secession inflamed questions of taxation, political representation, and constitutional change, and greatly complicated black aspirations during the state’s formative years. Moreover, long-standing attitudes on race and slavery held great sway throughout Appalachia. Thus, the quest by the state’s black residents to achieve the full measure of freedom in the immediate post-Civil War years faced formidable challenges.To meet the mandates for statehood recognition established by President Lincoln, the state’s legislators were forced to rectify a particularly troublesome conundrum: how to grant citizenship to the state’s black residents as well as to its former Confederates. While both populations eventually garnered the rights of citizenship, the fact that a significant number of southern West Virginia’s black residents departed the region suggests that the political gains granted to them were not enough to stem the tide of out-migration during the state’s formative years, from 1863 to 1870. 4 CICERO FAIN / EARLY BLACK MIGRATION IN CABELL COUNTY ARTICLE West Virginia’s formation divided many groups within the new state. Grievances born of secession inflamed questions of taxation, political representation, and constitutional change, and greatly complicated black aspirations during the state’s formative years. It must be remembered that in 1860 the black population in the Virginia counties comprising the current state of West Virginia totaled only 5.9 percent of the general population, with most found in the western Virginia mountain region.1 Moreover, long-standing attitudes on race and slavery held great sway throughout Appalachia. -

Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province

Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province, Virginia and West Virginia— A Field Trip Guidebook for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Eastern Section Meeting, September 28–29, 2011 Open-File Report 2012–1194 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Geology of the Devonian Marcellus Shale—Valley and Ridge Province, Virginia and West Virginia— A Field Trip Guidebook for the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Eastern Section Meeting, September 28–29, 2011 By Catherine B. Enomoto1, James L. Coleman, Jr.1, John T. Haynes2, Steven J. Whitmeyer2, Ronald R. McDowell3, J. Eric Lewis3, Tyler P. Spear3, and Christopher S. Swezey1 1U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA 20192 2 James Madison University, Harrisonburg, VA 22807 3 West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, Morgantown, WV 26508 Open-File Report 2012–1194 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Ken Salazar, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

Mathews Maxwell (1809 - 1862)

Mathews Maxwell (1809 - 1862) MATHEWS 2 MAXWELL was the son of William and Elizabeth Maxwell and was born 10 Oct 1809 in Tazewell, Va 1. He died 11 Apr 1862 in Raleigh County, WVA 2. He married JULIET ANN BROWN 19 Mar 1835 in Giles County, Va 3, she was the daughter of JOHN BROWN and REBECCA PEARIS. She was born 03 Aug 1814 in Mercer County, Va (WV) 4, and died 20 Aug 1896 in Cottageville, Jackson Co, WV 5. Mathews name is spelled with one "t" on his gravestone. It is also spelled Matthews in other sources. Matthews Maxwell is buried in Wildwood Cemetery, Beckley, WVA, tombstone dates are Oct 10, 1809 - April 11, 1862 (Raleigh County Cemeteries, Vol IV, page 53). He died from Typhoid Fever. He lies in the Maxwell plot adjacent to the Beckley plot. Juliet is buried in the Methodist Church Cemetery, Cottageville, WVA 7.. From the "Early Settlers of Raleigh Co. 1840-1850" MAXWELL, Matthews - A native of Tazewell County, Va., he came to the Marshes after living in Mercer County, later settling on Winding Gulf. Five sons, Whitley, Samuel, James, Robert, and John, were Union soldiers. John died in service. A. B. Maxwell of Beckley is the youngest child of Matthews. The "History of Scioto County, 1903 indicates that the family moved from Mercer to Wyoming County in 1847. The "History of Summers County, 1908" "(writing about James A. Maxwell) states that his father (James A.'s) moved from Clover Bottom to the Winding Gulf area (now Raleigh County) when he was 14 (i.e. -

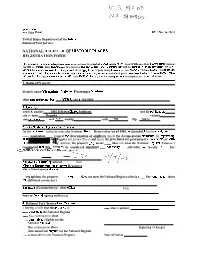

Nomination Form

(Rtv. 10-90) 3-I5Form 10-9fMN United States Department of the loterior National Park Service NATIONAL MGISTER OF HTSTORTC PLACXS REGISTRATION FORM Thiq fMm is for use in nomvlaring or requesting detnminatiwts for indin'dd propenies and di-. See immtct~onsin How m Cornplerc the National Regi~terof Wistnnc P1w.s Regaht~onForm (National Rcicpistcr Bullctin I6A) Complm each Item by mark~ng"x" m the appmprlalc box or b! entermp lhc mfommion requested If my ircm dm~wt apph to toe prombeing dwumemad. enter WfA" for "MIappliable." For functions. arch~tccruralclass~ficatron. materials, adarras of s~mificance.enm only -ones and subcak-gmcs from the rnswctions- Pl- addmonal enmcs md nmtive ncrns on continuation sheets MPS Form 10-9OOa). Use a tJ.pewritcr, word pmsor,or computer, to complete: all tterrus I. Name of Property historic name Virginian Railway Passenger Station other nameskite number VOHR site # 128-5461 2, Loration street & number 1402 Jefferson Street Southeast not for publica~ion city or town Roanoke vicinity state Veinia codcVA county code 770 Zip 24013 3. SlatelFderat Agencv Certification As the desipated authority under the National FIistoric Reservation An of 1986, as amended, 1 hereby certifj. that this -nomination -request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standads for regisrering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set fonh in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property -X- meets -does not meet the National Rcgister Criteria. I recommend that this pmwbe considered significant - nationally - statewide -X- locally. ( - See -~wments.)C ~ipnature~fcerti$ng official Date Viwinia De~srtrnentof Historic Resources Sme- or Federal agency rrnd bureau-- In my opinion, the property -meets -does not meet the National Register criteria. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Class War in West Virginia Education Workers Strike and Win!

Class War in West Virginia Education Workers Strike and Win! from the pages of suggested donation $3.00 Table of Contents Articles Page Education Workers Fighting Back in West Virginia! 1 By Otis Grotewohl, February 5, 2018 Statewide education strike looms in West Virginia 3 By Otis Grotewohl, February 20, 2018 Workers shut down West Virginia schools! 5 By Otis Grotewohl, February 26, 2018 Class war in West Virginia: School workers strike and win raise 8 By Martha Grevatt and Minnie Bruce Pratt, March 7, 2018 West Virginia education workers, teaching how to fight 12 Editorial, March 5, 2018 From a teacher to West Virginia educators: An open letter 14 By a guest author, March 5, 2018 Lessons of the West Virginia strike 16 By Otis Grotewohl, March 13, 2018 Is a ‘Defiant Workers’ Spring’ coming? 21 By Otis Grotewohl, March 20, 2018 Battle of Blair Mountain still rings true 23 By John Steffin, March 7, 2018 Solidarity Statements Page Harvard TPS Coalition Solidarity Statement 25 March 4, 2018 Southern Workers Assembly 26 March 1, 2018 USW Local 8751 29 March 5, 2018 Articles copyright 2018 Workers World. Verbatim copying and distribution of entire articles is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved. ii Education Workers Fighting Back in West Virginia! By Otis Grotewohl, February 5, 2018 www.tinyurl.com/ww180205og Teachers and school support staff are currently in motion in West Virginia. On Feb. 2, roughly 2,000 teachers and service employees from Mingo, Wyoming, Logan and Raleigh counties staged a walkout and took their message to the capitol. -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).