Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

Annual Financial Review of Scottish Premier League Football Season 2010-11 Contents

www.pwc.co.uk/scotland Calm before the storm Scottish Premier League Football 23nd annual financial review of Scottish Premier League football season 2010-11 Contents Introduction 3 Profit and loss 6 Balance sheet 18 Cashflow 24 Appendix one 2010/11 the season that was 39 Appendix two What the directors thought 41 Appendix three Significant transfer activity 2010/11 42 Introduction Welcome to the 23rd annual PwC financial review of the Scottish Premier League (SPL). This year’s report includes our usual in-depth analysis of the 2010/11 season using the clubs’ audited accounts. However, we acknowledge that given the dominance of Rangers1 demise over recent months, these figures may be looked at with a new perspective. Nevertheless, it is important to analyse how the SPL performed in season 2010/11 with Rangers and explore the potential impact the loss of the club will have on the league. Red spells danger? Notwithstanding the storm engulfing The impact the wider economy has had The Scottish game has never been Rangers, the outlook for season on football – as well as other sports - under more intense financial pressure. 2010/11 was one of extreme caution. shouldn’t be ignored. The continuing This analysis reinforces the need for squeeze on fans’ disposable incomes member clubs to continue seeking out Amidst fears of a double dip recession has meant that additional spending on effective strategies in order to operate within the wider economy, SPL clubs areas outside of the traditional season on a more sustainable financial footing, continued to further reduce their cost ticket package – from additional including cutting costs in the absence bases, particularly around securing domestic cup games to merchandise – of new revenue streams. -

Lanarkshire Bus Guide

Lanarkshire Bus Guide We’re the difference. First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 1 First Bus is one of Britain’s largest bus operators. We operate around a fifth of all local bus services outside London. As a local employer, we employ 2,400 people across Greater Glasgow & Lanarkshire, as well as offering a range of positions, from becoming a qualified bus technician to working within our network team or human resources. Our 80 routes criss-cross Glasgow, supplied by 950 buses. Within Lanarkshire we have 483 buses on 11 routes, helping to bring the community together and enable everyday life. First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 2 Route Frequency From To From every East Kilbride. Petersburn 201 10 min Hairmyres Glasgow, From every Buchanan Bus Overtown 240 10 min Station From every North Cleland 241 10 min Motherwell From every Holytown/ Pather 242 20 min Maxim From every Forgewood North Lodge 244 hour From every Motherwell, Newarthill, 254 10 min West Hamilton St Mosshall St Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 255 30 min Bus Station Station Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 263 30 min Bus Station Station From every Hamilton Newmains/Shotts 266 6 min Bus Station Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 267 10 min Bus Station Station First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 3 Fare Zone Map Carnbroe Calderbank Chapelhall Birkenshaw Burnhead Newhouse 266 to Glasgow 240 to Petersburn 242 NORTH 201 254 Uddingston Birkenshaw Dykehead Holytown LANARKSHIRE Shotts Burnhead LOCAL ZONE Torbothie Bellshill Newarthill 241 93 193 X11 Stane Flemington Hartwood Springhill -

Scottish Junior Cup Finals from the Secretary A~ YEAR RUNNER up 1942 /43 ROB ROY

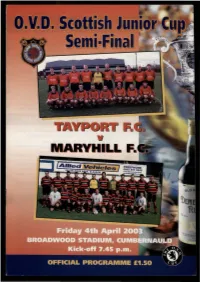

Sponsor's Welcome The Scottish Junior Cup Semi-Final Welcome to this evening's O.V.D. Cup match between Tayport and Maryhill - another East v West clash in the best traditions of the Cup. For Tayport, this is their second semi final in consecutive years. TAYPORT F.C. MARYHILL F.C. Colours - All white with red trimmings Colours: Red and Black It promises to be a thrilling encounter and O.V.D. would like to offer their congratulations to both Frazer FITZPATRICK Andy McCONDICHIE teams on reaching the penultimate round and wish both the very best of luck. It is an especially important round, certainly a hard one to lose having come so far, with the winning post - at the Scott PETERS Stephen MILLER very least a place in the final - so close at han,d. May the best team win. Grant PATERSON (Capt) Stephen GALLACHER The competition is very special to O.V.D. This is the 15th O.V.D. Cup and with a deal in place to take John WARD Graham MELDRUM us beyond that landmark, we are delighted to be coming back next year. We enjoy a superb Derek WEMYSS Paul WATSON relationship with the Scottish Junior Football Association and we look forward to the 16th O.V.D. Brian CRAIK Stephen CAMPBELL Cup in 2003/2004. It is only fitting that Scotland's premier junior football comp etition should be Allan RAMSAY Greig MacDONALD sponsored by the nations favourite leading dark rum . John CUNNINGHAM O.V.D. would like to say thank you to today's teams and their loyal followers for all their support Steven ST,EWART Ralph HUNTER eyan SMITH and enthusiasm . -

MINUTES Dalziel High School Parents Information Evening [email protected] 14/03/2016 @ 19:30 in Attendance

MINUTES Dalziel High School Parents Information Evening [email protected] 14/03/2016 @ 19:30 In Attendance Evelyn Dickson, Jacqui Agnew, Jan Chalmers, Anthony Paterson, Jacqui Friel, Lesley Wales, Lesley Shearer, Ruth Logan, Diane McLaughlan, Carolyn Steeds, Susan Malcolm, Sandra Ferguson, Wendy Hall, Paula Jeffreys, Elaine Hamilton, Karen Lannigan Apologies Leeann Rattigan, Caroline Wilson, Julie Mcleod, Laureen Vaughan, Patti Owens, Joanne Morrison Welcome Evelyn Dickson called the meeting to order by thanking all the parents for their attendance, and confirmed the previous minutes had been posted to the schools website for all to view. Jacqui Friel, PTA treasurer, informed us that, after paying the deposit for the quiz night and gifting £200 to each house for the choral shield, the PTA fund stands at £1200. A cheque was presented to Mr Robert Birch and it was agreed to discuss what the money should be used for at the next meeting. Rector’s Report Rector Robert Birch presented his report, copy of the full report can be found under the news column on the website, alternatively why not Subscribe to receive the Rector's Monthly newsletter direct to your inbox. https://www.dalzielhigh.org.uk/news/newsletter.html STAFFING - R.Birch informed the group about some staffing changes, Caroline Bleach has been appointed acting DHT when Fiona Conboy goes on Maternity leave. The school now requires an acting PT of pupil support for Greig house and interviews will take place on Wednesday 16 th March. The interviews for PT mathematics took place on Thursday 10 th March and Dr Leigh-Ann Scott was appointed. -

Annual Review 2006

Annual Review 2006 Show Racism the RED Card Scotland Staff Campaign Coordinator: Billy Singh Education Worker: Zoobia Aslam Support Worker: Tommy Breslin Contact Show Racism the Red Card Scotland GMB Union Fountain House 1-3 Woodside Crescent Glasgow G3 7UJ Tel: 0141 332 8566 Email: [email protected] Web: www.theredcardscotland.org Show Racism the RED Card Annual Review CONTENTS List of patrons 2 Campaign Coordinators report 3 Kick Off 2005 4 Fortnight of Action 2005 4 Asylum Seekers welcome here 5 Schools competition 2006 6 Star signings 6 Coaching with a Conscience 7 Fortnight of Action 2006 7 Player of the Year Awards 8 Next season 8 - 9 Support Workers report 11 Resources 12 Education & Grassroots 13 Supporters Initiatives and Music 14 Campaign Workers report 16 - 18 Events 20 - 28 Scotland 2006 1 SCOTTISH PATRONS: Marvin Andrews; Craig Beattie; Rainer Bonhof; Gerry Britton; Craig Brown; Richie Byrne; Mo Camara; Jason de Vos; Xander Diamond; Stuart Duff; Paul Elliott; Derek Ferguson; Craig Gordon; James Grady; Michael Hart; Mark Hateley; Colin Hendry; Tony Higgins; Jim Jefferies; Jim Leishman; Neil Lennon; Craig Levein; David Marshall; Gordon Marshall; Jamie McAllister; Stuart McCaffrey; Derek McIness; Alex McLeish; Jackie McNamara (Sr.); Tony Mowbary; Ian Murray; Hamed Namouchi; Robbie Neilson; Pat Nevin; Barry Nicholson; Colin Nish; Phil O'Donnell; Martin O'Neill; Steven Pressley; Nigel Quashie; Mark Reynolds; Colin Samuei; Brent Sancho; Jason Scotland; Gary Smith; Jamie Smith; Walter Smith; Michael Stewart; Andy Walker; -

Local Advertising WORKS!

Spring 2018 – Motherwell 1 LANARKSHIRE ADVERTISING LOCAL ADVERTISING for LOCAL PEOPLE Local Advertising WORKS! Support your local traders Keep up to date with what’s on in your area Emergency contacts & much more... The PERFECT interior design look at a FRACTION of the cost! QUALITY • CONVENIENCE • SERVICE FREE ESTIMATES www.sunnydazeblinds.co.uk Tel: 01698 322 819 CASH FOR CLOTHES Cash4ClothesScotland Ltd All attendants carry scales to Lanarkshire’s Local Family weigh your items and you get Have you ever asked Run Business. paid before they leave your yourself where does it go? premises. We also work with Established 6 years ago with schools in the local area. This Well, we re-use all the items our 1st store opening at Merry allows them the opportunity to that we accept, and they are St, Motherwell. We have been raise funds for whatever reason distributed Locally, Eastern overwhelmed with the support it may be. (Coach Hire, New Europe, Africa & India. we have attained and are Books, Apparatus etc) All communities that are continuing to expand throughout underprivileged by any Lanarkshire to accommodate It also makes kids aware that means benefit from your high demand. recycling is no1 way to a greener planet or even to help someone unwanted items. It's a great Meanwhile we are still offering less fortunate than themselves. feeling allowing individuals to support to small independent dress themselves with dignity, charities within the locality that Our Company Goals: pride & style and helped to boost are looking for ways to raise • Helping Build Communities their self-esteem. So, if you want money for their special cause. -

Download Glasgow Tour Mapbook

Steps for Stephen Spring / Summer 2022 Glasgow Tour Mapbook MAIN EVENT SPONSOR – BREWPACK, LONDON Fundraising in support of the Darby Rimmer MND Foundation Glasgow Tour To Ibrox Stadium To Fir Park Supporting the Darby Rimmer MND Foundation To Hampden Park To Celtic Park To Broadwood Stadium Steps for Stephen Walkers Rota 3 Steps for Stephen Stage 1 – St Mirren FC to Inchinnan 4 • 0.0 – Head back up Murray Street • 0.5 – Straight over the lights into Albion Street • 0.6 – Turn left at the end into Love Street • 1.3 – Take the 2nd exit at the roundabout and head under the M8 • 1.7 – Straight on at the mini roundabout (2nd exit) by the Air Cargo Centre • 2.8 – Turn left at the lights onto Greenock Road and cross the river • 3.7 – Turn right at the Braehead Tavern onto Old Greenock Road • 4.3 – Handover at the bus stop at the junction with Park Road Steps for Stephen • 0.0 – Head up park road following it round toe the left at the end into the footpath over the bridge. • 0.2 – At the end of the footpath, turn left on St Annes Wynd and head down the footpath straight ahead as the road bends to the right • 0.3 – at the end of the footpath, turn right on Park Drive • 0.8 – Turn right into Park Wood and then take the steps down between the houses on the right, then at the end of the passage, turn left on the footpath. • 0.9 – Turn right up the footpath and immediately turn left under the cut-through to Mains Hill • 1.0 – Turn left out of Mains Hill onto Mains Hill • 1.1 – By the railings, follow the path up to the main road, cross the road and -

Semis-2005.Pdf

RENFREW • •• ...----·· ,. --•.·-·-.-•- :,,,- OFFICIAL PROGRAMME £1.50 The Scottish Junior Cup Semi-Final RENFREW F.C. -, IN THE EVENT OF A DRAW AFTER NINETY MINUTES If the teams are still level at MANAGER - Keith Burgess ASSISTANT MANAGER - Stewart MANAGER - Mick Dunlop Williamson ASSISTANT MANAGER - Billy Peacock COACH - Derek Carr COACH - Colin Lindsay PHYSIO - Norrie Marshall PHYSIO - Ally Cameron THIS EVENING'S PROGRAMME MATCH OFFICIALS Tonight's programme has been produced by Peter Runde, 4 6 REFEREEStevie Nicholls (Motherwell) ~~h~J°~1t~~e;c~iti~a~~~~r ~i~b~i7:~s~i~i~ti~~BSG on The editor would also like to extend his thanks to the ASSISTANTREFEREES officials of all the semi-finalists for their ready and willing 1st Official - Stephen O'Reilly {Glasgow) ~::!~~c;~~id~~~p!l~r;pJ:~~ p~~~:a;~:nt~:wina~cr•!t,u~f; 2nd Official - Gary Hilland (Glasgow) Oswald and Keith Burgess of Tayport. 4th OFFICIALDerek Nicholls {Motherwell) The photographs of Renfrew's ground is courtesy of Paul Crankshaw and the Renfrew team picture is courtesy of Kathleen M. Sinclair (01505) 359440). Tayport photographs are courtesy of DC Thomson. TONIGHT'S MATCH BALL (01382 223131 ). OLD PROGRAMMES - The editor is always interested in hearing from anyone who has any pre- 1970 Scottish The SJFA would like to thank MITREfor proarammes, and particularly old Junior programmes, providing the match ball for tonight's semi-final. particularly relating to the Scottish Junior Cup. So 1fyou can help please get in touch at the above address or telephone (01382) 330356. CoachHire available 01292 613500 .stagecoachbus.com Welcome to this evenings O.V.D. -

First Division Clubs in Europe Clubs De Première Division En Europe Klubs Der Ersten Divisionen in Europa

First Division Clubs in Europe Clubs de première division en Europe Klubs der ersten Divisionen in Europa Address List - Liste d’adresses - Adressverzeichnis 2008/09 First Division Clubs in Europe Clubs de première division en Europe Klubs der ersten Divisionen in Europa Address List – Liste d’adresses – Adressverzeichnis 2008/09 Union des associations européennes de football Legend – Légendes – Legende MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS Communication : This section provides the full address, phone and fax numbers, as well as the email and internet addresses of the national association. In addition, the names of the key officers are given: Pr = President, GS = General Secretary, PO = Press Officer. Facts & Figures : This section gives the date of foundation of the national association, the year of affiliation to FIFA and UEFA, as well as the name and capacity of any national stadium. In addition, the number of regis- tered players in the different divisions, the number of clubs and teams, as well as the number of referees within the national association are listed. Domestic Competition 2007/08 : This section provides details of the league, cup and, in some cases, league cup competitions in each member association last season. The key to the abbreviations used is as follows: aet = after extra time, pen = after a penalty shoot-out. First Division Clubs This section gives details all top division clubs of the national associations for the 2008/09 season (or the 2008 season where the domestic championship is played according to the calendar year), indicating the full address, phone and fax numbers, email and internet addresses, as well as the name of the stadium and of the press officer at the club (PO). -

The Scottish Football Association Handbook 2018

THE SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LTD HANDBOOK 2018/2019 No. 5453 CERTIFICATE OF INCORPORATION I HEREBY CERTIFY that ‘THE SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIMITED’ is this day incorporated under the Companies Act, 1862 to 1900, and that this Company is Limited. Given under my hand at Edinburgh, this Twenty-Ninth day of September, One thousand nine hundred and three. KENNETH MACKENZIE Registrar of Joint-Stock Companies CONTENTS CLUB DIRECTORY 4 ASSOCIATIONS AND LEAGUES 34 REFEREE OPERATIONS 40 MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION 48 ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION 51 BOARD PROTOCOLS 113 CUP COMPETITION RULES 136 REGISTRATION PROCEDURES 164 ANTI-DOPING REGULATIONS 219 OFFICIAL RETURNS 2018/2019 Aberdeen FC – SPFL – PREMIERSHIP S Steven Gunn G 01224 650400 Pittodrie Stadium B 01224 650458 Pittodrie Street M 07912 309823 Aberdeen AB24 5QH F 01224 644179 M Derek McInnes E [email protected] G Pittodrie Stadium W www.afc.co.uk Kit Description 1st Choice 2nd Choice Jersey Red Jersey Chalk Pearl with Grey flashes Shorts Red Shorts Chalk Pearl with Grey flashes Socks Red Socks White with Grey flashes Airdrieonians FC – SPFL – LEAGUE 1 S Stuart Shields M 07921 126268 Penny Cabs Stadium E [email protected] Excelsior Park, Craigneuk Avenue W www.airdriefc.com Airdrie, ML6 8QZ M Stephen Findlay G Penny Cabs Stadium Kit Description 1st Choice 2nd Choice Jersey White with Red Diamond Jersey Red with White Pinstripe Shorts White Shorts Red Socks White Socks Red Albion Rovers FC – SPFL – LEAGUE 2 S Colin Woodward G 01236 606334 Cliftonhill Stadium M 07875 666840 -

The Sports Grounds and Sporting Events (Designation) (Scotland

Document Generated: 2018-02-02 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. SCHEDULE 1 Article 2(a) and (b) SPORTS GROUNDS Allan Park Cove Balmoor Stadium Peterhead Bayview Stadium Methil Bellslea Park Fraserburgh The Bet Butler Stadium Dumbarton Borough Briggs Elgin Broadwood Stadium Cumbernauld Cappielow Park Greenock Celtic Park Glasgow Central Park Cowdenbeath Christie Park Huntly Claggan Park Fort William Cliftonhill Stadium Coatbridge Dens Park Stadium Dundee Dudgeon Park Brora East End Park Dunfermline Easter Road Stadium Edinburgh Energy Assets Arena Livingston Excelsior Stadium Airdrie The Falkirk Stadium Falkirk Ferguson Park Rosewell Firhill Stadium Glasgow Fir Park Stadium Motherwell Forthbank Stadium Stirling Galabank Annan Gayfield Park Arbroath Glebe Park Brechin Global Energy Stadium Dingwall Grant Park Lossiemouth Grant Street Park Inverness Hampden Park Glasgow Harlaw Park Inverurie 1 Document Generated: 2018-02-02 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. Harmsworth Park Wick The Haughs Turriff Ibrox Stadium Glasgow Islecroft Stadium Dalbeattie K Park East Kilbride Kynoch Park Keith Links Park Stadium Montrose McDiarmid Park Perth Mackessack Park Rothes Meadowbank Stadium Edinburgh Meadow Park Castle Douglas Mosset Park Forres Murrayfield Stadium Edinburgh Netherdale 3G Arena Galashiels New Douglas Park Hamilton North Lodge