Civil Society Engagements with Neoliberalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burn It Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985

Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 by Eryk Martin M.A., University of Victoria, 2008 B.A. (Hons.), University of Victoria, 2006 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Eryk Martin 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Eryk Martin Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Title: Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 Examining Committee: Chair: Dimitris Krallis Associate Professor Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor Roxanne Panchasi Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Professor Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Joan Sangster External Examiner Professor Gender and Women’s Studies Trent University Date Defended/Approved: January 15, 2016 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This dissertation investigates the experiences of five Canadian anarchists commonly knoWn as the Vancouver Five, Who came together in the early 1980s to destroy a BC Hydro power station in Qualicum Beach, bomb a Toronto factory that Was building parts for American cruise missiles, and assist in the firebombing of pornography stores in Vancouver. It uses these events in order to analyze the development and transformation of anarchist activism between 1967 and 1985. Focusing closely on anarchist ideas, tactics, and political projects, it explores the resurgence of anarchism as a vibrant form of leftWing activism in the late tWentieth century. In addressing the ideological basis and contested cultural meanings of armed struggle, it uncovers Why and how the Vancouver Five transformed themselves into an underground, clandestine force. -

Darryl Adams Fonds Poster Collection Descriptions RBSC-ARC-1753

Darryl Adams fonds Poster collection descriptions RBSC-ARC-1753 Identifier Title Date created Extent Scope and content Poster promoting event featuring Don Luce, Jeanne Friedman and a film titiled "A 8 posters : col. ; Question of Torture". Sponsored by Vancouver American Exiles Association and RBSC-ARC-1753-35-01 South Vietnamese Political Prisoners [between 1936-1988] 28 x 43 cm Spartacus Bookstore. Poster promoting event featuring Jack Scott (of Patti Hearst fame) speaking on his new [Friday 18 January 2 posters : col. ; book. A Spartacus Bookstore Forum. Come & bring a friend to 130 W. Hastings Friday RBSC-ARC-1753-35-02 Sweat and Struggle Working Class Struggles in Canada 1974] 28 x 43 cm Jan. 18 - 8pm Poster promoting an Now Here LSD 49 Interactive, Multi-Media Psycho-Sonic Event November 1st and 2nd in Deep Space (club) on 936 Main Street, rear entry on Station St. 2 posters : b&w Doors at 10. Image of an overweight businessman with glasses, white dress shirt and tie RBSC-ARC-1753-35-03 Now Here: An Interactive, Multi-Media Psycho-Sonic Event LSD 49 [between 1936-1988] ; 28 x 43 cm under text. 1 poster : b&w ; Poster promoting Now Here LSD 49. Black and white image of an overweight RBSC-ARC-1753-35-04 Now Here LSD 49 [between 1936-1988] 28 x 43 cm businessman with glasses, white dress shirt and tie between text. Poster promoting a public meeting, march and rallies and SFU and UBC, and Chilean 4 posters : col. ; Pena for solidarity with the Chilean struggle and resistance. Supported by the Coalition RBSC-ARC-1753-35-05 Solidarity with the Chilean Struggle and Resistance [between 1936-1988] 28 x 43 cm for Chilean Solidarity. -

I Three Part Path

Journal of Radical Shimming Issue 9 I Three Part Path: A brief X Punk Politics? Or lack guide to making a pilgrimage for the thereof? A Punk House is only a purpose of reforming your relation- Pedagogical Beginning ship to the landscape P. 89 Cassie Troyan P. 0, 17 Mike Wolf XI An Introduction to the II Feral Children, Civilized Introduction to “After the Fall” Gaze: Adapting to the Wild Mirror P. 93 Gabriel Saloman P. 24 Robin Hustle XII Introduction to After III Cascadia Journal 1907, the Fall 1912 (from F I L M) P. 95 P. 1, 29 Ola Ståhl1 XIII January 7, 2010 in Reggie’s Journal of Radical Shimming 9 Journal IV Vedem House Soul Food Restaurant in P. 37 Matthew Stadler Detroit, Michigan P. 108 V Dear Laura, P. 2, 43 Dan S. Wang XIV LIVING FOR CHANGE: Re-Imagining America, Re-Creating VI Flatlands: Non-Hierarchical Ourselves Space and its Uses P. 4, 113 Grace Lee Boggs P. 3, 52 Sam Gould XV First Encounter at the VII Introduction to Boggs Center “MYSTERY ECOLOGY” (2009) P. 115 Dan S. Wang P. 75 Gabriel Saloman XVI Half of a quick report-back VIII Introduction to “Media- from the January 7 Boggs Center tion, Self-Marginalization and Post meeting Politics in Protest Media” (2009) P. 117 Mike Wolf P. 78 Robby Herbst XVII Varieties of Craft, IX A Conversation between Smoothness, Alchemical Pedagogy Sam Gould, Gabriel Saloman and P. 4, 119 Dylan Gauthier Robby Herbst concerning the You- Tube School for Social Politics XVIII Late night talkback assess- P. -

Prison Justice Network Resources Spring 2019 Unceded Kwantlen, Katzie, and Semiahmoo Lands (Surrey, BC)

Prison Justice Network resources Spring 2019 unceded Kwantlen, Katzie, and Semiahmoo lands (Surrey, BC) (with thanks to PASAN for permission to use its and Red Dress Productions’ image, above) INSIDE: resources by, for, & with prisoners/detainees - inspiration, context, & communities! Stark Raven “first Monday of each month” June 3, July 1, August 5 (7-8pm) Co-op Radio 100.5FM stream http://coopradio.org Starchoice #845 “featuring in-depth interviews, news and analysis” “we Cover: Canadian prison conditions, detention & the war on terror, alternatives to prison, psychiatric survivor movements, criminalization of migration & poverty, privatization, security certificates, government policy, political prisoners, policing, the death penalty, the personal & political impacts of incarceration, prisoner’s writings.” c/o Co-op Radio, 110-360 Columbia St., Vancouver, BC Coast Salish Territory V6A 4J1 http://prisonjustice.ca/stark-raven Prisoner Letter Writing “First Saturday of every month!” http://spartacusbooks.net/events July 6, August 3 (3-5pm) Spartacus Books, 3378 Findlay Street, Vancouver, BC V5N 4E7 “Come to Spartacus Books to write a letter to a prisoner pen-pal. We can help you find a pen-pal if you've never had one before. We also have stamps, envelopes, and guidelines for how to write a letter. As always, there's free coffee and tea.” https://facebook.com/events/296491164409741 Write to Detainee by End Immigration Detention Network https://endimmigrationdetention.com send letters of support inside the prison walls to a detainee from Nigeria being held in Ontario who has spoken up against the immigration detention system and has consented to receiving mail: Akin Akinsuyi, Toronto East Detention Centre, 55 Civic Road, Scarborough, ON M1L 2K9 “Prisons are notorious for censoring mail, especially mail with perceived political or ‘anti-social’ content. -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

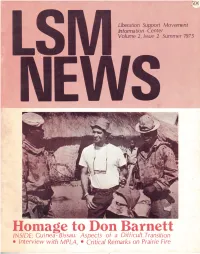

Homage to Don Barnett INSIDE: Guinea- Bissau: Aspeccts of a Difficult Transition • Interview with MPLA, • Critical Remarks on Prairie Fire -Contents

soq Liberation Support Movement Information Center Volume 2, Issue 2 Summer 197 5 Homage to Don Barnett INSIDE: Guinea- Bissau: Aspeccts of a Difficult Transition • Interview with MPLA, • Critical Remarks on Prairie Fire -contents HOMAGE-TO DON BARNETT 1 COMM EMO RA TIO NS 3 SOLIDARITY MESSAGES 5 TO THE GUARDIAN RADICAL FORUM 7 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 11 ... ACTIONS Vietnamese Revolutionaries in Vancouver 12 LSM East Coast Unit LSM Bay Area Unit LSM Yanc.ouver Group EXCERPTS FROM "BOBBIUE: INDIAN REBEL" 15 GUINEA-BISSAU: ASPECTS OF A DIFFICULT TRANSITION 16 Impressions from a liberated people "We don't Accept. Being Treated Like Animals" Contradictions of a Lagging City " ... Since Pidjigufti We Never Looked Back." ANGOLA: THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES ~29 Interview with Paulo Jorge, MPLA CRITICAL REMARKS ON "PRAIRIE FIRE" 35 COPYRIGHT@ 1975 LSM PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Liberation Su~ort Movement, Box 94338 Richmond, B-C~CANADA. V6V 2A8 ISSN 0315-1840 Cover Pho.to .by .. LSM: ,Don .Barnett with MPLA .militants in Eastern Angola, 1968a Don Barnett at LSM Seminar held in August 1974. Dear Friends & Comrades It is with both sorrow and profound regret that we inform you of the death of Don Barnett, founder and first Chairman of Liberation Support Movement. His death on 25 April 1975, caused by a heart attack at the early age of 45, is a tremendous loss for us and all who struggle for proletarian internationalism and socialism. On 10 January 1930 Don was born into a poor Jewish family residing in Los Angeles. With his many abilities and abundant energy Don could have been "successful II in any number of professions. -

Industrial Worker (Winter 2017).Pdf

WINTER 2017 #1778 VOLUME 114 NO. 1 $4 (U.S. IWW members) / $6 (U.S. non-members) / $7 (International) solidarity in adversity Foreground: Wobblies march in Festival of Resistance in DC, Jan. 20, 2017. Background: Women’s March on Washington, Jan. 21. 2 Industrial Worker • Winter 2017 IWW DIRECTORY IWW Contract Shops Queensland Secretary: Dave Pike, secretary@ Lithuania: lithuania.iww@gmail. Kentucky Utica IWW: Brendan Maslauskas California Brisbane GMB: P.O. Box 5842, West iww.org.uk com Kentucky GMB: Mick Parsons, Dunn, del., 315-240-3149. End, Qld 4101. Asger, del., hap- Southern England Organiser: Nikki Netherlands: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer, papamick.iww@ Ohio San Francisco Bay Area GMB: [email protected]. Dancey, [email protected] gmail.com. 502-658-0299 P.O. Box 11412, Berkeley, 94712. Norway IWW: 004793656014. Northeast Ohio GMB: P.O. Box 1096, 510-845-0540. [email protected]. Victoria Tech Committee: [email protected] [email protected]. http://www. Louisiana Cleveland, 44114. 440-941-0999 Melbourne GMB: P.O. Box 145, Training Department: Chair - Chris iwwnorge.org, www.facebook.com/ Louisiana IWW: John Mark Crowder, Contact for: Berkeley Ecology Center iwwnorge. Twitter: @IWWnorge Ohio Valley GMB: P.O. Box 6042, (Curbside) Recycling - IU 670 IWW Moreland, VIC 3058. melbourne- Wellbrook, [email protected] del, [email protected]. https:// Cincinnati 45206, 513- 510-1486, Shop; Community Conservation [email protected]. Treasurer: Jed Forward, treasurer@ United States www.facebook.com/groups/iwwof- [email protected] Centers (Buyback) Recycling – IU Canada iww.org.uk Alabama nwlouisiana/ Maine Sweet Patches Screenprinting: 670 – IWW Shop; Stone Mountain IWW Canadian Regional Organizing West of Scotland Organiser: Rona Mobile: Jimmy Broadhead, del., P.O. -

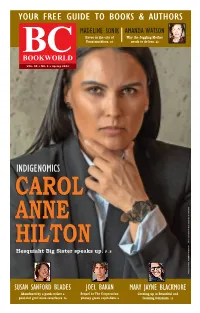

Spring 2021 Volume 35

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS MADELINE SONIK AMANDA WATSON Havoc in the city of Why the Juggling Mother Fountainebleau. 24 needs to do less. 22 BCBOOKWORLD VOL. 35 • NO. 1 • Spring 2021 INDIGENOMICS CAROLCAROL PRODUCTIONS EYE SALISH ANNEANNE , THOMAS TRICIA BY HILTONHILTON PHOTO #40010086 Hesquiaht Big Sister speaks up. P.8 AGREEMENT MAIL PUBLICATION SUSAN SANFORD BLADES JOEL BAKAN MARY JAYNE BLACKMORE Abandoned by a punk rocker a Sequel to The Corporation: Growing up in Bountiful and post-riot grrrl mom resurfaces. 26 phoney green capitalism. 6 learning feminism. 13 PRINTED??????/TARA / BEV It’s a Great Season to Buy Local Good Morning, Takaya Takaya’s Journey Time to Wonder – Volume 1 Birding for Kids Cheryl Alexander and Alex Van Tol Cheryl Alexander and Jenaya Copithorne Sue Harper and S. Lesley Buxton A Guide to Finding, Identifying, and Photographing Birds in Your Area The remarkable story of Vancouver Told in verse and containing details of A colourful, fun, and fact-filled kid’s Damon Calderwood and Donald E. Waite Island’s lone wolf, Takaya, is told in this Takaya’s life, this picture book introduces guide to BC’s regional museums in charming, lyrical picture book for infants. young readers to Takaya, the lone wolf. the Thompson-Okanagan, Kootenays, A fun, educational guide to watching birds $12 bb | $10 pb | $5.99 ebook $20 hc | $15 pb | $9.99 ebook and Cariboo-Chilcotin. in their natural habitat. RMB | Rocky Mountain Books RMB | Rocky Mountain Books $22 pb | $10.99 ebook $19.95 pb | $15.99 ebook RMB | Rocky Mountain Books -

A Student's Guide on What a Zine Is and Tips on How to Make

A Student’s Guide on What a Zine Is and Tips on How to Make One Version 2.0 (2004) by Matt Holdaway What is a zine? Pronounced like “magazine” without the “maga” A zine is an independently created publication. It is often created by any means necessary and/or available, more often done out of passion for a subject rather than for commercial success. Currently, zines are typically photocopied using word processors, but there are many who utilize offset printing or create handmade zines with content made using collage, digital photography, silkscreen, litho, hand-written creative writing, etc. A zine can be about any subject and done in any style imaginable. Some typical subjects for content are creative writing, comics, personal writings, fan-based writings, science fiction, literature, anthology/art, and review, however it is completely open. A person with access to a photocopier can be writer, publisher, and printer. Nothing is easy, everything is possible. The quickest method from idea to print is to self- publish. The most control one could have over the content and appearance of a publication is to self-publish. A Brief History of Publishing The oldest known woodblock printing in the world is the Darani Sutra , found inside Seokga Pagoda of Bulguksa Temple, Korea, printed before 751 A.D. This sutra predated the Japanese Million Pagoda. The Darani Sutra dated to 770 A.D. Chinese printers used wood blocks with characters carved into them, which were then inked and transferred to paper in the 8th century. In the 11th century, Pi Sheng created a form of moveable type allowing for letters to be rearranged. -

2012 Bookfair Zine-New.Indd

AK Press BC Blackout Birdog Collective Black Banner Distro Black Cat Press Black Paw Print Black Raven Records Camas Books & Infoshop The Co!nspire Collective The Constellation of Revolt Publications Darklab Studios El Libertario Distro Island Sexual Health Center Janet Rogers/Ojistah Publishing Jeffrey Shantz John Bell Kate Sharpley Library Little Black Cart MediaNet MicroCosm Press Ministry of Casual Living Of Course You Can! Distro One Way Ticket Outhouse Treasury Occupy Vancouver People’s Library PM Press Poly 101 Red Lion Press Robert Graham Spartacus Books (secret people) distro Thoughtcrime Ink Tom Swanky Unlawful Combatant Distro VIC Forest Action Network Vancouver Island Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.) Vancouver Island Public Interest Research Group (VIPIRG) Victoria Pleasure Salon Victoria Street Newz Warrior Publications UVic Women’s Center Woodland Deer Statement of Indigenous Solidarity The Victoria Anarchist Bookfair Collective supports the struggles of Indigenous peoples throughout North America to assert their cultural autonomy and territorial sovereignty. Victoria is located on the traditional overlapping territories of the Songhees and Esquimalt peoples, who have endured the seizure of their land and repeated attempts to obliterate their culture through multiple forces of colonization. The resilience and strength of these and other communities, who make ancestral connections to this region in the face of injustice, challenges us to support them and all Indigenous people in the ongoing struggle against colonialism, capitalism, and cultural genocide. Page 1 Page 14 Victoria Anarchist Bookfair Volunteers: We would like to extend a gracious “thank-you” to everyone who Statement of Principles made this year’s bookfair possible. -

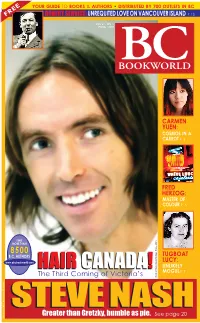

Spring 2007 Volume 21

YOUR GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS • DISTRIBUTED BY 700 OUTLETS IN BC FREE ROBERT SERVICE: UNREQUITED LOVE ON VANCOUVER ISLAND P. 13 VOL. 21 • NO. 1 SPRING • 2007 BOOKWORLDBC CARMEN YUEN: COSMOS IN A CARROT P. 5 FRED HERZOG: MASTER OF COLOUR P. 5 FIND MORE THAN 8500 B.C. AUTHORS TUGBOAT www.abcbookworld.com LUCY: HAIRHAIR CANADA!CANADA! UNLIKELY MOGUL P. 9 The Third Coming of Victoria’s Photo of Steve Nash (Heritage House, 2007) STEVESTEVE NASHNASH Greater than Gretzky, humble as pie. See page 20 Publication Mail Agreement #40010086 WORLD Morna E. Gregory and Sian James in Ephesus, Turkey. Here we go loop-dee-loo SPECIAL shoveling horse manure opaque walls once the latch has been ISSUE hether or not they used all of the in an Alberta riding sta- turned. 142 remarkable facilities featured ble, Gregory and James Others are crude but ingenious—like W have become far-flung the Bolivian toilet carved out of a giant You won’t find it on Google. But some of you might like to know in Toilets of the World (Merrell $22.95), dung management ex- cactus. this year marks the 200th anniversary of perts—providing photos Some johns are historic, like Johannes- gleeful globetrotters Morna E. self-publishing from or about B.C., dat- and write-ups for a de- burg’s first public lavatory, built in 1911, ing from the first edition of John Gregory and Sian James don’t say. lightful array of drawer- or New Delhi’s Museum of Toilets. Jewitt’s memoirs. dropping depots. Others are spooky and intimidating, At BC BookWorld we have consist- But the Vancouver pair have cer- Toilets of the World includes every- like a solitary toilet in the middle of a ently provided coverage of independ- tainly gone to great ends to compile one thing from a solid gold toilet belonging Namibian desert. -

Summer 2016 #1777 Volume 113 No. 3 $4 (Us Iww

SUMMER 2016 #1777 VOLUME 113 NO. 3 $4 (U.S. IWW members) / $6 (U.S. non-members) / $8 (International) 2 Industrial Worker • Summer 2016 IWW DIRECTORY IWW Contract Shops Queensland Secretary: Dave Pike, secretary@ Lithuania: lithuania.iww@gmail. Kentucky Utica IWW: Brendan Maslauskas California Brisbane GMB: P.O. Box 5842, West iww.org.uk com Kentucky GMB: Mick Parsons, Dunn, del., 315-240-3149. End, Qld 4101. Asger, del., hap- Southern England Organiser: Nikki Netherlands: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer, papamick.iww@ Ohio San Francisco Bay Area GMB: [email protected]. Dancey, [email protected] gmail.com. 502-658-0299 P.O. Box 11412, Berkeley, 94712. Norway IWW: 004793656014. Northeast Ohio GMB: P.O. Box 1096, 510-845-0540. [email protected]. Victoria Tech Committee: [email protected] [email protected]. http://www. Louisiana Cleveland, 44114. 440-941-0999 Melbourne GMB: P.O. Box 145, Training Department: Chair - Chris iwwnorge.org, www.facebook.com/ Louisiana IWW: John Mark Crowder, Contact for: Berkeley Ecology Center iwwnorge. Twitter: @IWWnorge Ohio Valley GMB: P.O. Box 6042, (Curbside) Recycling - IU 670 IWW Moreland, VIC 3058. melbourne- Wellbrook, [email protected] del, [email protected]. https:// Cincinnati 45206, 513- 510-1486, Shop; Community Conservation [email protected]. Treasurer: Jed Forward, treasurer@ United States www.facebook.com/groups/iwwof- [email protected] Centers (Buyback) Recycling – IU Canada iww.org.uk Alabama nwlouisiana/ Maine Sweet Patches Screenprinting: 670 – IWW Shop; Stone Mountain IWW Canadian Regional Organizing West of Scotland Organiser: Rona Mobile: Jimmy Broadhead, del., P.O. [email protected] & Daughters fabrics - IU 410 IWW Committee (CANROC): c/o Toronto McAlpine, westscotland@iww.