Philip James Elliot Was Born on Oct. 8, 1927, in Portland, OR, to Fred and Clara Elliot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameron Townsend: Good News in Every Language Free

FREE CAMERON TOWNSEND: GOOD NEWS IN EVERY LANGUAGE PDF Janet Benge,Geoff Benge | 232 pages | 05 Dec 2001 | YWAM Publishing,U.S. | 9781576581643 | English | Washington, United States William Cameron Townsend - Only One Hope He graduated from a Presbyterian school and attended Occidental College in Los Angeles for a time but did not graduate. He joined the National Guard inpreparing to go to war for his country. Before he had any assignments from the military, he spent some time with Stella Zimmerman, a missionary who was on furlough. You are needed in Central America! Cameron Townsend was unhappy about being called a coward and chose to pursue the missions call instead. He requested to be released from soldier service and to be allowed to become a Cameron Townsend: Good News in Every Language overseas instead. Over the next year he traveled through Latin America. During this time, he met another missionary who felt called to Latin America named Elvira. The two married in July He spread the Gospel in Spanish but felt that this was not accessible to the indigenous people of the country. For this reason, he went to Santa Catarina and settled in a Cakchiquel community where he learned the native language. He spent fourteen years there, learning and then translating the Bible into the local language. He started a school and medical clinic, and set up a generator of electricity, a plant to process coffee, and a supply store for agriculture. Townsend felt that the standard missionary practices neglected some of the needs of the people, as well as ignoring the cultures and languages of many of the groups. -

Word and Work

"Holding fast the Faithful Word ■■ • ■ * The Word and Work CQ "Holding forth the Word of Life." November - December, 2005 INCONCEIVABLE LOVE- STUNNING FORGIVENESS INCREDIBLE TRANSFORMATION! AUCAS!! 50 Yrs Later DON'T Let the Rush of the Holidays Keep you from reading this month's VrE-R-Y VALUABLE Articles!!! Then SHARE them with others. * * "All married couples, all missionaries and all Christians should read this article!" Which article? Check it out for yourself. * * * "When it comes time to die, make sure that all you have to do is die." -Jim Elliot Vital Information for Students Hoping to Enter College! The June 2005 W&W had an article~S.CC. Lives On through S.C.E.C. It explained that some scholarship funds are available to students from churches that formerly supported Southeastern Christian College. 12 colleges (see below) now participate in this program. Read on, and act soon or it will be too late! Important and Time-Sensitive Announcement Regarding College Scholarships From: Hughes Jones, 130 Jackson Pike, Harrodsburg, KY 40330. Telephone: 859 734-7197. Email: [email protected] For: Southeastern Christian Education Corporation, 476 Sparrow Lane, Harrodsburg, Ky 40330 Date: October 17, 2005 Southeastern Christian Education Corporation Announcement: Prospective college students desiring to have an SCEC financial aid grant included in their aid package for the 2006/07 school year are encouraged to complete their college admission process prior to Feb ruary 01, 2006. This date should allow the participating college finan cial aid offices time needed to prepare requests for assistance from Southeastern Christian Education Corporation before anticipated dead lines. -

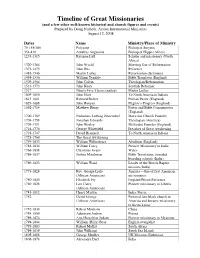

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Operation Auca Was an Attempt by Five American Missionaries to Bring the Gospel to the Waorani People in Ecuador

Operation Auca was an attempt by five American missionaries to bring the Gospel to the Waorani people in Ecuador. On January 8, 1956, all five men—including Jim Elliot and Nate Saint, —were attacked and speared by a group of Waorani warriors. A few years later, the widow and young daughter of Jim Elliot, Elisabeth & Valerie, and the sister of Nate Saint returned to the same jungle tribe as missionaries, eventually leading to the conversion of many. Gather a group together and come hear Valerie Elliot Shepard, the daughter Elisabeth Elliot, and her husband, Walt Shepherd, speak in Orange City on November 2 & 3, with a men’s breakfast event ($5, 9-10:30 AM) and women’s conference ($10, 9 AM -2 PM , lunch included). Get your tickets before prices go up this Tuesday, the 15th! Visit your local Radio Shack or shepards.eventbrite.com by TOMORROW night. Also mark your calendar for the free session Friday night, Nov. 2nd at the Unity Knight Center from 7-8:30; free-will offering Email [email protected] with any questions. These events are sponsored by OC area churches, businesses and community members. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - But, What Would Jesus Do (WWJD), about Immigration? An Insightful and Inspirational Event worth attending! Hear Dr. Jason Lief of Northwestern College speak on the history of immigration & unpack misconceptions. Hear life stories of Dreamers Not taking political positions, just considering, What Would Jesus Do? Tuesday, October 30 7:00PM Sioux Falls Ministry Center, 225 E. 11th St., Sioux Falls, South Dakota - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - The annual Katelyn’s Fund Orphan Ministry Auction, scheduled for November 2, is receiving monetary and merchandise donations. -

Jim Elliott Kyla Usher 12 Grade Jim Elliot Was a Zealous Christian

Jim Elliott Kyla Usher 12th grade Jim Elliot was a zealous Christian missionary who evangelized to the people of Ecuador. Jim grew up in Portland, Oregon, and trusted in Christ as his Savior when he was just a little boy. After graduating high school, Jim Elliot went to Wheaton College, and his burden for the inhabitants of Central America grew stronger. However, after graduating college, Jim wasn’t clear of God’s will for his life, so in 1950 he moved to Oklahoma to study unwritten languages at the Summer Institute of Linguistics, and it was there that he felt God was leading him to minister to the people of Ecuador. Jim Elliot’s Accomplishments Jim Elliot’s life and testimony affected the Christian church in many positive ways. He evangelized the Auca Indians and led many of them to Christ. Despite the danger Jim faced, he continued in his journey to witness to the Ecuadorian people because he knew that was God’s will for his life. Because of this, Jim Elliot inspired several people to go into the mission field, and his story is still affecting the lives of missionaries today. While on his journey, Jim Elliot wrote journals and letters, many of which were published. These journals tell of his life while in Ecuador and the different experiences he encountered. These writings still help people to have a firm foundation in Christ and to grow in Him. Jim’s faith encourages Christians to face their fears with courage and the belief that God knows what’s best for us. -

Newsletter May 2020

MAY 2020 NEWSLETTER Several years later Mincaye and I were part of an ITEC training team in Hyderabad, India. As Mincaye helped our US dentist train Indian Pastors to It Wasn’t My Idea pull teeth, I suddenly realized how short-sighted I had been thinking that the by Steve Saint Waodani could never go to a place like Papua New Guinea to teach skills. In India, highly educated and dedicated pastors could not share Christ’s Gospel You know how fast you have to run to get away from an angry bear? Just a because the people they wanted to evangelize would not let Christians into little bit faster than the next guy! Do you know how much missions their communities. Grandfather Mincaye was not on an adventure trip. The experience you need to have to be considered to be an expert on the Indian pastors had specifically asked for Mincaye to go with the ITEC team. I subject? You got it! think they knew how we North Americans prefer to do the work ourselves rather than to equip national Christ-followers with skills that open doors to When people comment on what a great idea it was to start ITEC instead of once closed communities. just “doing missions for the Waodani,” I feel I need to confess: It wasn’t my idea. The Waodani idea was not new. Jesus went from community to community meeting hurting people’s felt needs. That is why the multitudes followed Him. My aunt Rachel had just died and I had flown down to represent my family in But even when thousands of people wanted to hear His message, Jesus burying her out in the jungles where she had lived with the Waodani for the concentrated on teaching God’s message to twelve uneducated and last 36 years of her life. -

Archival Research on Missionaries and the Waorani Dr

Picture with a Thousand Pieces: Archival Research on Missionaries and the Waorani Dr. Kathryn Long October 5, 2017 Introduction Thanks to the BGC Archives for the invitation, also for prayers and encouragement from many in the audience during a challenging year. Tonight, I want to talk about using archives, and specifically the Graham Center Archives, to do research for a book I’ve written that is in the final stages of editing (I hope!). Its title is God in the Rainforest: Missionaries Among the Waorani in Amazonian Ecuador. It traces the story of missionary interaction with the Waorani, an isolated group of indigenous people in the Ecuadorian Amazon, between 1956 and about 1994. Contact between missionaries and the Waorani, then called “aucas,” began with an event familiar to many people in this room: the deaths of five young missionaries in 1956, speared as they tried to make peaceful contact with the Waorani. Two years later, two missionary women—Elisabeth Elliot, the widow of one of the slain men and Rachel Saint, the sister of an another, with the help of a Waorani woman named Dayuma—successfully contacted the Waorani and began efforts to introduce them to Christianity and end the violence that was destroying their culture. [Slide 1] The sacrificial deaths of the five men and subsequent efforts to Christianize the Waorani became the defining missionary narrative for American evangelicals during the second half of the twentieth century. It certainly was the most widely publicized. Here are a few of the books, and, more recently, the films, that told the story. -

Through Gates of Splendor Book Discussion Guide

Through Gates of Splendor Book Discussion Guide Chapter I: “I Dare Not Stay Home” Describe Jim Elliot. What was he like? What were some of the life experiences that shaped Jim into the man he was? How did Jim know that God wanted him to spend his life as a missionary in Ecuador? What kind of man was Pete Fleming? Pete Fleming wrote, “A call is nothing more nor less than obedience to the will of God, as God presses it home to the soul by whatever means He chooses” (page 22). Can you think of any times when you were absolutely sure of the will of God? What are some ways we can make ourselves more open to hearing God’s voice? Chapter II: Destination: Shandia Before you began to read this book, what did you know about the life and culture of Ecuador? Which elements of Ecuadorian culture do you think were most appealing to the missionaries? Which posed challenges? Based on the brief historical sketch of Ecuador given in this chapter, what might have been some of the Ecuadorians’ assumptions about foreigners, and vice versa? Chapter III: “All Things to All Men” The portrait of Venancio (pages 41-42) describes the daily life of a typical Quichua native. How does this compare with daily life where you live? In what ways does the Quichua birthing experience (pages 43-45) differ from a typical Western birth? What do you think this story signifies about Quichua attitudes toward children and family life? Toward medicine? Why is it so important—beyond basic communication—for missionaries to become as fluent as possible in the native language of those they are trying to reach? Chapter IV: Infinite Adaptability Describe Ed McCully. -

Newsletter Jan 2021

JANUARY 2021 NEWSLETTER Christ followers in low-tech environments (low-tech does not Why ITEC Exists mean low intelligence), training Christ followers to meet felt needs as a door opener for the Gospel, and equipping others to do the by Jaime same (both domestically and globally). A number of years ago, a couple was visiting ITEC as part of the This interdependent relationship with our Christian brothers and process to determine if God was calling them to be a part of our sisters around the world is the vision that continues to drive ITEC team. At the end of the week, they came into my office and asked today. The Great Commission was given to every Christ follower, what they would do if they were to move across the country to and there is a role for every Christ follower to play. join us. I explained that prayerfully considering and submitting to God whether they felt called to work at ITEC was the first thing we Each of us has been given gifts to be used to further this mission. needed to be sensitive to. Then, as long as their calling to ITEC Romans 12:4-8 says, “For just as each of us has one body with was confirmed, we could begin to discuss the unique role God many members, and these members do not all have the same had them to play on our team. function, so in Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others. We have different ITEC was started on the principle that every Christ follower has a gifts, according to the grace given to each of us. -

The Journals of Jim Elliot : Missionary, Martyr, Man of God Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE JOURNALS OF JIM ELLIOT : MISSIONARY, MARTYR, MAN OF GOD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Elisabeth Elliot | 480 pages | 21 Apr 2020 | Baker Publishing Group | 9780800729455 | English | Ada, MI, United States The Journals of Jim Elliot : Missionary, Martyr, Man of God PDF Book Other editions. They were at the beginning of their adult life, and they had headed off to the field. We thought he'd make a great politician. Summary : This special graduation gift book offers wisdom for the journey of life. Through it all, she says, there is only one reliable path, and if you walk it, you will see the transformation of all your losses, heartbreaks, and tragedies into something strong and purposeful. At the age of 28, he left behind a young wife, a baby daughter, and an incredible legacy of faith. What encouraged me the most about this book, though, was how it reveals the progression of growth God works in the life of a person. The Journals of Jim Elliot will intrigue fans of Jim and Elisabeth Elliot, readers interested in missions, and young people struggling to find God's plan for their lives. There is so much substance to his words and his Bible study entries are deep and rich with lessons. Aug 01, Joanna Sue rated it it was amazing. Subject to credit approval. But flame is often short-lived. Summary : When life gets too busy, too impersonal, and too much to handle, it's time to turn to God for some peace and quiet. Basil of Caesarea. Sort order. Again, not a bad book Now repackaged for the next generation of Christians, Discipline: The Glad Surrender shows readers how to - discipline. -

Bridge of Blood Program V7.Indd

They died on January 8, 1956. Fifty years later, we remember Th e Cast (from left to right) theirtheir couragecourage and and their their mission. mission. Front Row: Rebecca Baker, Christen Price, Laura Ransom, Amanda Joy Martin, Kathleen MacNeil, and Sarah Searles Bridge Back Row: Shawn Green, Grant Knight, Nicholas Wood, Dan Keslar, d[ and Chris Moran Blood: Taking Christ to the Aucas By David H. Robey January 8-13, 2006 Cedarville University Dixon Ministry Center Recital Hall Home to 3,100 Christian students, Cedarville University is an accredited, Christ-centered Baptist university of arts, sciences, professional, and graduate programs. Cedarville off ers the quality majors, world-class facilities, caring professors, and award-winning technology you would expect from a university that U.S.News & World Report, Th e Princeton Review, and Peterson’s Competitive Colleges all recognize as one of the top in the Midwest. Each year major employers, law schools, medical schools, and seminaries visit campus to recruit our graduates. Daily chapels, discipleship groups, outreach ministries, and Bible classes challenge students to know God and fully enjoy their relationship with Him. Th is is Cedarville University. Inspiring. “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose.” Jim Elliot 1929-1956 Two days after this picture was taken of Nate Saint and an Auca Indian, Nate and his four 1-800-CEDARVILLE (233-2784) missionary friends were killed by Auca lances. WWee RRestest OOnn Th eeee Th e CCedarvilleedarville UUniversityniversity (FFinlandiainlandia) CChristianhristian MMinistriesinistries DDivisionivision ppresentsresents WWee rrestest oonn Th eee,e, OOurur SShieldhield aandnd OOurur DDefender!efender! WWee ggoo nnotot fforthorth aalonelone aagainstgainst tthehe ffoe,oe, SStrongtrong iinn Th y sstrength,trength, ssafeafe iinn Th y kkeepingeeping ttenderender WWee rrestest oonn Th eee,e, aandnd iinn Th y nnameame wwee ggo.o. -

The Cloud of Witnesses

The Cloud of Witnesses Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved. How, then, can they call on the one they have not believed in? And how can they believe in the one of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone preaching to them? And how can anyone preach unless they are sent? As it is written: “How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!” - Romans 10:13-15 Bear with each other and forgive one another if any of you has a grievance against someone. For- give as the Lord forgave you. And over all these virtues put on love, which binds them all to- gether in perfect unity. - Colossians 3:13-14 Elisabeth Elliot - Elisabeth Elliot (1926-2015) was a mis- sionary to the Huaorani people of Ecuador and a prominent Christian author and speaker. Her first husband, Jim Elliot, had been martyred by Huaorani tribesmen in 1956 along with four other missionaries. Elisabeth told their story in the landmark book Through Gates of Splendor, which in- spired an entire generation of new Christian missionaries. She, along with mission part- ner Rachel Saint, continued their ministry to the Huaorani, eventually translating the Bi- ble into their language and encouraging the growth of the Huaorani church. Elliot then returned to the US, where she ministered through writing and speaking. Timeline of the Elliots’ Ministry in South America: 1952 – Jim and Elisabeth both go separately to live in Ecuador. They had already met and started dating at Wheaton College, but both were committed to making their mission work take priority over all else.