Santa Cruz County Before the Arizona Navigable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona TIM PALMER FLICKR

Arizona TIM PALMER FLICKR Colorado River at Mile 50. Cover: Salt River. Letter from the President ivers are the great treasury of noted scientists and other experts reviewed the survey design, and biological diversity in the western state-specific experts reviewed the results for each state. RUnited States. As evidence mounts The result is a state-by-state list of more than 250 of the West’s that climate is changing even faster than we outstanding streams, some protected, some still vulnerable. The feared, it becomes essential that we create Great Rivers of the West is a new type of inventory to serve the sanctuaries on our best, most natural rivers modern needs of river conservation—a list that Western Rivers that will harbor viable populations of at-risk Conservancy can use to strategically inform its work. species—not only charismatic species like salmon, but a broad range of aquatic and This is one of 11 state chapters in the report. Also available are a terrestrial species. summary of the entire report, as well as the full report text. That is what we do at Western Rivers Conservancy. We buy land With the right tools in hand, Western Rivers Conservancy is to create sanctuaries along the most outstanding rivers in the West seizing once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to acquire and protect – places where fish, wildlife and people can flourish. precious streamside lands on some of America’s finest rivers. With a talented team in place, combining more than 150 years This is a time when investment in conservation can yield huge of land acquisition experience and offices in Oregon, Colorado, dividends for the future. -

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

Roundtail Chub Repatriated to the Blue River

Volume 1 | Issue 2 | Summer 2015 Roundtail Chub Repatriated to the Blue River Inside this issue: With a fish exclusion barrier in place and a marked decline of catfish, the time was #TRENDINGNOW ................. 2 right for stocking Roundtail Chub into a remote eastern Arizona stream. New Initiative Launched for Southwest Native Trout.......... 2 On April 30, 2015, the Reclamation, and Marsh and Blue River. A total of 222 AZ 6-Species Conservation Department stocked 876 Associates LLC embarked on a Roundtail Chub were Agreement Renewal .............. 2 juvenile Roundtail Chub from mission to find, collect and stocked into the Blue River. IN THE FIELD ........................ 3 ARCC into the Blue River near bring into captivity some During annual monitoring, Recent and Upcoming AZGFD- the Juan Miller Crossing. Roundtail Chub for captive led Activities ........................... 3 five months later, Additional augmentation propagation from the nearest- Department staff captured Spikedace Stocked into Spring stockings to enhance the genetic neighbor population in Eagle Creek ..................................... 3 42 of the stocked chub, representation of the Blue River Creek. The Aquatic Research some of which had travelled BACK AT THE PONDS .......... 4 Roundtail Chub will be and Conservation Center as far as seven miles Native Fish Identification performed later this year. (ARCC) held and raised the upstream from the stocking Workshop at ARCC................ 4 offspring of those chub for Stockings will continue for the location. future stocking into the Blue next several years until that River. population is established in the Department biologists conducted annual Blue River and genetically In 2012, the partners delivered monitoring in subsequent mimics the wild source captive-raised juvenile years, capturing three chub population. -

Environmental Flows and Water Demands in Arizona

Environmental Flows and Water A University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center Project Demands in Arizona ater is an increasingly scarce resource and is essential for Arizona’s future. Figure 1. Elements of Environmental Flow WWith Arizona’s population growth and Occurring in Seasonal Hydrographs continued drought, citizens and water managers have been taking a closer look at water supplies in the state. Municipal, industrial, and agricul- tural water users are well-represented demand sectors, but water supplies and management to benefit the environment are not often consid- ered. This bulletin explains environmental water demands in Arizona and introduces information essential for considering environmental water demands in water management discussions. Considering water for the environment is impor- tant because humans have an interconnected and interdependent relationship with the envi- ronment. Nature provides us recreation oppor- tunities, economic benefits, and water supplies Data Source: to sustain our communities. USGS stream gage data Figure 2: Human Demand and Current Flow in Arizona Environmental water demands (or environmental flow) (circle size indicates relative amount of water) refers to how much water is needed in a watercourse to sustain a healthy ecosystem. Defining environmental water demand goes beyond the ecology and hydrol- Maximum ogy of a system and should include consideration for Flows how much water is required to achieve an agreed Industrial 40.8 maf Industrial SW Municipal upon level of river health, as determined by the GW 1% GW 8% water-using community. Arizona’s native ani- 4% mals and plants depend upon dynamic flows commonly described according to the natural Municipal SW flow regime. -

Cienegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American

Hendrickson and Minckley Cienegas of the American Southwest 131 Abstract Cienegas The term cienega is here applied to mid-elevation (1,000-2,000 m) wetlands characterized by permanently saturated, highly organic, reducing soils. A depauperate Vanishing Climax flora dominated by low sedges highly adapted to such soils characterizes these habitats. Progression to cienega is Communities of the dependent on a complex association of factors most likely found in headwater areas. Once achieved, the community American Southwest appears stable and persistent since paleoecological data indicate long periods of cienega conditions, with infre- quent cycles of incision. We hypothesize the cienega to be an aquatic climax community. Cienegas and other marsh- land habitats have decreased greatly in Arizona in the Dean A. Hendrickson past century. Cultural impacts have been diverse and not Department of Zoology, well documented. While factors such as grazing and Arizona State University streambed modifications contributed to their destruction, the role of climate must also be considered. Cienega con- and ditions could be restored at historic sites by provision of ' constant water supply and amelioration of catastrophic W. L. Minckley flooding events. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Dexter Fish Hatchery Introduction and Department of Zoology Written accounts and photographs of early explorers Arizona State University and settlers (e.g., Hastings and Turner, 1965) indicate that most pre-1890 aquatic habitats in southeastern Arizona were different from what they are today. Sandy, barren streambeds (Interior Strands of Minckley and Brown, 1982) now lie entrenched between vertical walls many meters below dry valley surfaces. These same streams prior to 1880 coursed unincised across alluvial fills in shallow, braided channels, often through lush marshes. -

June 2021 Arizona Office of Tourism Monthly State Parks Visitation Report

June 2021 Arizona Office of Tourism Monthly State Parks Visitation Report Arizona State Park Visitation June June 2021 2020 YTD State Park % Chg 2021 2020 YTD YTD % Chg Alamo Lake SP 1,237 1,924 -35.7% 48,720 46,871 3.9% Buckskin Mountain SP 11,092 9,292 19.4% 49,439 45,627 8.4% Catalina SP 6,598 2,420 172.6% 154,763 156,234 -0.9% Cattail Cove SP 10,138 14,908 -32.0% 52,221 67,256 -22.4% Colorado River SHP 167 57 193.0% 2,589 6,220 -58.4% Dead Horse Ranch SP 17,142 18,748 -8.6% 126,799 120,044 5.6% Fool Hollow Lake RA 16,380 25,104 -34.8% 55,360 63,341 -12.6% Fort Verde SHP 706 521 35.5% 4,672 2,654 76.0% Granite Mountain Hotshots MSP 1,076 1,380 -22.0% 11,778 14,874 -20.8% Homolovi SP 4,032 1,982 103.4% 22,007 11,470 91.9% Jerome SHP 4,099 1,991 105.9% 21,789 14,109 54.4% Kartchner Caverns SP 7,776 2,045 280.2% 44,020 57,663 -23.7% Lake Havasu SP 66,040 74,493 -11.3% 241,845 337,920 -28.4% Lost Dutchman SP 4,198 3,651 15.0% 122,844 132,399 -7.2% Lyman Lake SP 11,169 10,625 5.1% 30,755 38,074 -19.2% McFarland SHP 166 0 1,213 2,942 -58.8% Oracle SP 270 486 -44.4% 6,994 9,191 -23.9% Patagonia Lake SP 25,058 30,706 -18.4% 118,311 126,873 -6.7% Picacho Peak SP 1,893 1,953 -3.1% 64,084 68,800 -6.9% Red Rock SP 12,963 6,118 111.9% 56,356 33,228 69.6% Riordan Mansion SHP 777 0 2,188 2,478 -11.7% River Island SP 2,623 3,004 -12.7% 18,089 19,411 -6.8% Roper Lake SP 8,049 12,394 -35.1% 52,924 49,738 6.4% Slide Rock SP 54,922 33,491 64.0% 231,551 110,781 109.0% Tombstone Courthouse SHP 2,875 1,465 96.2% 18,261 16,394 11.4% Tonto Natural Bridge SP 8,146 7,161 13.8% 54,950 36,557 50.3% Tubac Presidio SHP 261 117 123.1% 4,240 2,923 45.1% Yuma Territorial Prison SHP 2,206 1,061 107.9% 28,672 26,505 8.2% Total All Parks 282,059 267,097 5.6% 1,647,434 1,620,577 1.7% Note: Dankworth Pond SP data is included in Roper Lake SP, Sonoita Creek SNA is included in Patagonia Lake SP and Verde River Greenway SNA is included in Dead Horse Ranch SP. -

The Arizona Nature Conservancy Conservancy 300 East University Boulevard, Suite 230, Tucson, Arizona 85705 (602) 622-3861

The Nature The Arizona Nature Conservancy conservancy 300 East University Boulevard, Suite 230, Tucson, Arizona 85705 (602) 622-3861 Memorandum To: Dan Campbell From: Peter Warren Re: Arizona native fishes Date: 26 August 1987 Here is some general information about the status oi native fish in Arizona and the Arizona Nature Conservancy's role in protecting threatened native fish. The pre-settlement fish fauna of Arizona consisted of 31 species of freshwater fish. Through introduction of exotic species, the number of resident fish in Arizona is now over 100 species. Many of the exotic species are either predatory upon or in competition with native species. A combination of introduced exotic species and loss of perennial stream habitat has sharply reduced the number and size of native fish populations. Of the 31 original native fish, one is extinct and four are extirpated in Arizona. Approximately half of the remaining native fish are currently listed or proposed for listing as Threatened or Endangered. Although recovery measures are being undertaken, the future of several of the endangered fish is by no means secure. For example, Woundfin survives only in a small part of the Virgin River and its small population could be easily destroyed. Major losses of native fish populations continue to occur. We have Just learned that all of the Mexican populations of Desert Pupfish in the Colorado River delta were apparently destroyed during the last three years due to introduction of Tilapia into the populations by floodwaters of 1983. The single most important factor in protecting the remaining native fish populations is preservation of habitat and insuring stable stream flows. -

Water, Summer 2008

Restoring Connections Vol. 11 Issue 2 Summer 2008 Newsletter of the Sky Island Alliance In this issue: A River Runs Beneath It by Randy Serraglio 4 Time and the Aquifer: Models and Long-term Thinking Water… by Julia Fonseca 5 Street and Public Rights-of-Way: Community Corridors of Heat & Dehydration OR Green Belts of Coolness & Rehydration by Brad Lancaster 6 A New Path for Water Use by Melissa Lamberton 7 The Power of Water by Janice Przybyl 8 Our special pull-out section on Ciénegas Monitoring Water with Remote Cameras by Sergio Avila 9 Waste Water / Holy Water by Ken Lamberton 10 Coyote Wells by Julia Fonseca 12 Finding Water in the Desert by Gary Williams 12 H2Oly Stories by Doug Bland 13 Restaurant Review: The Adobe Café & Bakery by Mary Rakestraw 14 Volunteers Make It Happen Rio Saracachi at Rancho Agua Fria in Sonora. by Sarah Williams 16 From the Director’s Desk: Swimming Holes and Groundwater by Matt Skroch, Executive Director Rivers and springs have been used to our several decades, or centuries, the water table will agricultural advantage for 12,000 years here, once again seep upwards to ground level, and though unsustainable groundwater mining is a those low points on the landscape we call rivers relatively new phenomena. We’ve discovered will flow once again. other temporary ways around the problem of increasing water scarcity — billions of dollars Either choice will eventually lead nature back to spent to pump water uphill for 330 miles being better days. The difference being that one choice Few experiences compare to the exhilaration of one spectacular example. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

San Pedro River Study Area Wild and Scenic River Eligibility Report

Prepared by the USDI Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, Tucson Field Office May 2016 The BLM manages more than 245 million acres of public land, the most of any Federal agency. This land, known as the National System of Public Lands, is primarily located in 12 Western states, including Alaska. The BLM also administers 700 million acres of sub-surface mineral estate throughout the nation. The BLM's mission is to manage and conserve the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations under our mandate of multiple-use and sustained yield. Cover photo – San Pedro River near Charleston courtesy of BLM/Bob Wick 2 San Pedro River Wild and Scenic River Study Area Eligibility Report This document consolidates resource information about the San Pedro River and one of its key tributaries, the Babocomari River. The purpose of this document is to provide a basis for reassessing the eligibility and suitability for inclusion of the San Pedro River and related free- flowing conditions and outstandingly remarkable river values into the National Wild and Scenic River System. I. BACKGROUND: The San Pedro River Wild and Scenic River Study Area Eligibility Report describes the information considered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in the eligibility, and tentative re-classification of the San Pedro River for suitability analysis in the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA) Resource Management Plan (RMP). The SPRNCA was established by Public Law (P.L.) 100-696 on Nov. 18, 1988 to preserve, protect, and enhance the aquatic, wildlife, archaeological, paleontological, scientific, cultural, educational, and recreational resources in the conservation area. -

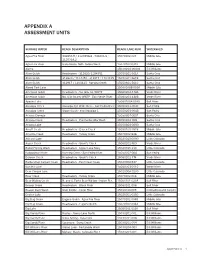

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Flood Insurance Study Vol. 1

SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, ARIZONA AND INCORPORATED AREAS VOLUME 1 OF 3 Community Community Name Number SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 040090 NOGALES, CITY OF 040091 PATAGONIA, TOWN OF 040092 Santa Cruz County EFFECTIVE: DECEMBER 2, 2011 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 04023CV001A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this FIS report may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map (FBFM) panels (e.g., floodways, cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows: Old Zone(s) New Zone A1 through A30 AE B X C X Initial Countywide FIS Report Effective Date: December 2, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS – VOLUME 1 Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION