Improving Mental Health Services in Systems of Integrated and Accountable Care: Emerging Lessons and Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The NHS in Wales: Structure and Services (Update)

The NHS in Wales: Structure and services (update) Abstract This paper updates Research Paper 03/094 and provides briefing on the structure of the NHS in Wales following the restructuring in 2003, and further reforms announced by the First Minister in 2004. May 2005 Members’ Research Service / Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau Members’ Research Service: Enquiry Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Ymholiad The NHS in Wales: Structures and Services (update) Dan Stevenson / Steve Boyce May 2005 Paper number: 05/ 023 © Crown copyright 2005 Enquiry no: 04/2661/dps Date: 12 May 2004 This document has been prepared by the Members’ Research Service to provide Assembly Members and their staff with information and for no other purpose. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information is accurate, however, we cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies found later in the original source material, provided that the original source is not the Members’ Research Service itself. This document does not constitute an expression of opinion by the National Assembly, the Welsh Assembly Government or any other of the Assembly’s constituent parts or connected bodies. Members’ Research Service: Enquiry Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Ymholiad Members’ Research Service: Enquiry Gwasanaeth Ymchwil yr Aelodau: Ymholiad Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2 Recent reforms of the NHS in Wales................................................................... 2 2.1 NHS reforms in Wales up to April 2003 ................................................................. 2 2.2 Main features of the 2003 NHS organisational reforms ......................................... 2 2.3 Background to the 2003 NHS reforms ................................................................... 3 2.4 Reforms announced by the First Minister on 30 November 2004........................... 4 3 The NHS in Wales: Commissioners and Providers of healthcare services .... -

Assurance and Accreditation News

Get in touch Call us on 01789 761600, visit www.chks.co.uk or email [email protected] Issue 21 Assurance and Winter 2013 Accreditation News of our dementia dashboard and standards and consultancy Highlights from 2013 support, which make up the assurance programme. 2013 has been a year for consolidation The standards development team, as always, has continued and reflection following the significant to develop and maintain our programmes of standards. The changes in 2012. This year we said main achievement was the publication of the International goodbye to Ruth Wright, a long term Accreditation Programme for healthcare organisations 2013. client manager, who has left us for Updated using a patient pathway approach, and the modules as the pleasures of retirement which we a framework, we are excited by the end product which is a step hope she is embracing. In the summer, forward from the 2010 standards. Other programmes completed we were shocked by the sudden death of Julie Hyde, our in 2013 were the domiciliary standards and the oncology Accreditation Awards Panel chairman, which is a great loss to standards. The primary care standards are out for consultation, us. Her legacy will remain in the many structures and processes and work is very much underway on revising the hospice and implemented during her tenure and the memory of her ‘matter care home standards for completion in the first half of 2014. of fact’ approach to life. Alan Corry Finn has now taken on the chairmanship. Regulation and inspection As a result of the Francis, Keogh and Berwick reports there has Celebrating success been notable change in the regulation and inspection of health At our Top Hospitals ceremony in May, Guy’s and St Thomas’ and social care organisations in hospital was the winner of the dementia care award for their the UK this year. -

Piloting Data Linkage in a Prospective Cohort Study of a GP Referral Scheme to Avoid Unnecessary Emergency Department Conveyance Joanna M

Blodgett et al. BMC Emergency Medicine (2020) 20:48 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-020-00343-w RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Piloting data linkage in a prospective cohort study of a GP referral scheme to avoid unnecessary emergency department conveyance Joanna M. Blodgett1,2* , Duncan J. Robertson2,3, David Ratcliffe2,4,5 and Kenneth Rockwood6 Abstract Background: UK Ambulance services are under pressure to safely stream appropriate patients away from the Emergency Department (ED). Even so, there has been little evaluation of patient outcomes. We investigated differences between patients who are conveyed directly to ED after calling 999 and those referred by an ambulance crew to a novel GP referral scheme. Methods: This was a prospective study comparing patients from two cohorts, one conveyed directly to the ED (n = 4219) and the other referred to a GP by the on-scene paramedic (n = 321). To compare differences in patient outcomes, we include follow-up data of a smaller subset of each cohort (up to n = 150 in each) including hospital admission, history of long-term illness, previous ED attendance, length of stay, hospital investigations, internal transfers, 30-day re-admission and 10-month mortality. Results: Older individuals, females, and those with minor incidents were more likely to be referred to a GP than conveyed directly to ED. Of those patients referred to the GP, only 22.4% presented at ED within 30 days. These patients were more likely to be admitted then than were those initially conveyed directly to ED (59% vs 31%). Those conveyed to ED had a higher risk of death compared to those who were referred to the GP (HR: 2.59; 95% CI 1.14–5.89), however when analyses were restricted to those who presented at ED within 30 days, there was no difference in mortality risk (HR: 1.45; 95% CI 0.58–3.65). -

Developing the Scrutiny of NHS Services

Page 239 Agenda Item 12 SCRUTINY COMMISSION : 18 JUNE 2003 OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY OF THE HEALTH SERVICE REPORT OF THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE PURPOSE 1 The purpose of this report is to set out the current position with regard to the implementation of the provisions in the Health and Social Care Act 2001 enabling Social Services Authorities to scrutinise the actions of NHS bodies. The item has been placed on the agenda at the request of Mr S Galton, CC. BACKGROUND Health Bodies 2 It is important at the outset of this report to identify the health bodies with responsibility for strategic issues and the delivery of services to the area of Leicestershire. Clearly, over time the number of such bodies and their responsibilities may change. Thus, new Care Trusts may be created from existing partnership arrangements, as has been the case with the development of Primary Care Trusts from Primary Care Groups over recent years. In Leicestershire the relevant health bodies are as follows: • Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland Strategic Health Authority • University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust • Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust • East Midlands Ambulance Services NHS Trust • Eastern Leicester PCT • Leicester City West PCT • Melton, Rutland and Harborough PCT • Hinckley and Bosworth PCT • Charnwood and North West Leicestershire PCT • South Leicestershire PCT DM/health scrutiny Page 240 In addition, many residents of Leicestershire receive health services from NHS bodies based in other Social Services authority areas : examples are hospitals in Kettering, Northampton, Nuneaton, Coventry, Burton, Derby, Nottingham and Grantham. The extent to which members of authorities in Leicestershire may be involved in scrutiny of these bodies will depend on arrangements for scrutiny made elsewhere and is not therefore discussed further in this report. -

Primary Care Commissioning Committees Meeting in Common

Cannock Chase Clinical Commissioning Group South East Staffordshire and Seisdon Peninsula Clinical Commissioning Group Stafford and Surrounds Clinical Commissioning Group Primary Care Commissioning Committees Meeting in Common to be held on 30 May 2018 at 2.00 pm am in the Rudyard Suite, Staffordshire Place 2, Stafford ST16 2LP AGENDA A=Approval R=Ratification S=Assurance I=Information D=Discussion Enc Lead A/R/S/I Timing 1. Welcome by the Chair Verbal AHe - 2.00 2. Apologies Verbal AHe - 3. Quoracy Verbal AHe - Declarations of Interests and actions taken to 4. Enc. 01 AHe I manage conflict 5. Minutes of the Meeting held on 26 April 2018 Enc. 02 AHe A 6. Actions Sheet Enc. 03 AHe A 2.10 Assurance 7. Risk Register Enc. 04 SJ S 2.15 Strategic and Planning 8. Extended Access Specification Enc. 05 LM/VO I 2.25 9. Patient Participation Groups Enc. 06 SH S 2.35 Items for Information 10. 3600 Stakeholder Survey Enc. 07 LM I 2.50 11. Head of Primary Care National Update Enc.08 RB I 3.00 Any Other Business 12. Questions from Members of the Public - All D 3.15 Glossary of terms 13. Enc. 09 All I - Glossary of Terms Date, Time and venue of next meeting 28 June 2018 at 2.00 pm in the Aquarius 14. - All A 3.30 Ballroom, Cannock TO BE RESCHEDULED We are honest, accessible Quality is our day job We innovate and deliver Care and respect for all and we listen Cannock Chase Clinical Commissioning Group South East Staffordshire and Seisdon Peninsula Clinical Commissioning Group Stafford and Surrounds Clinical Commissioning Group CANNOCK CHASE CLINICAL -

From Good to Great Supplement Editor VEN E T INSIDE Jennifer Taylor S Sub Editor Hsj.Co.Uk Trevor Johnson, David Devonport CONTENTS Design Jennifer Van Schoor

AN HSJ SUPPLEMENT/4 maRch 2010 LEADERSHIPIN ASSOCIATION WITH thE nationaL LEADERshiP coUnciL TOP LEADERS FROM GOOD TO GREAT Supplement editor VEN E T INSIDE Jennifer Taylor S Sub editor hsj.co.uk Trevor Johnson, David Devonport CONTENTS Design Jennifer van Schoor FOREWORD OPINION TOP LEADERS PROGRAMME NHS chief executive Sir Karen Lynas spells DAME BARBARA HAKIN David Nicholson explains out how the Top why a more systematic Leaders Programme Great leaders inspire their people to deliver willingly approach to NHS will work. more than they could ever have otherwise done. And recruitment will find the Page 2 the NHS is not short of such talented, committed, best people for key hard-working leaders who go the extra mile every day positions. to help their teams make services better for patients. Page 1 The National Leadership Council recognises the huge contribution that leadership makes to patient care and has created a range of supporting programmes – a board development programme, programmes for emerging and clinical leaders, a programme to support the inclusion of leaders from PROFILING diverse backgrounds and a programme for our most senior leaders, the Top Leaders Programme. The days of fierce, charismatic These national programmes build on the leadership leaders like General Patton are development in every individual organisation and over. Now those who command most across every region. Additionally, we have reached a respect are people-centred and watershed in how the NHS manages its most senior grounded in reality. We take a look talent, now overtly recognising that we need to spot at the new qualities needed to be a and nurture those people who are ready for the next great leader. -

Governing Board Meeting

CCG Headquarters 4th Floor 1 Guildhall Square (Civic Offices) Portsmouth PO1 2GJ Governing Board Meeting A meeting will be held from 3.00pm – 5.00pm on Wednesday 18 March 2020 in Conference Room A, 2nd Floor, Civic Offices, Portsmouth AGENDA Subject Lead Attachment 1. Apologies for Absence and Welcome Dr E Fellows Verbal Apologies received from Dr Nick Moore. 2. Register and Declarations of Interest Dr E Fellows Pink 3. Minutes of Previous Meeting Dr E Fellows White a. To agree the minutes of the Governing Board meeting held on Wednesday 15 January 2020. b. Matters Arising 4. Chief Clinical Officer’s Report Dr L Collie Blue 5. Health and Care Portsmouth and Wider Systems I Richens a. Portsmouth Verbal b. Portsmouth and South East Hampshire Verbal c. Hampshire and Isle of Wight Verbal 6. Finance and Performance Reports M Spandley a. Finance Report Cream b. Performance Report White c. Programme Highlight Report Cream 7. Quality and Safeguarding Report I Richens White 8. Governing Board Assurance Framework and Corporate I Richens Cream Risk Register 9. 2020-21 Operating Plan – 1st Cut M Spandley White 10. Financial Strategy and Budget Setting 2020/21 M Spandley Cream 11. Full Register of Interest (All Staff) Dr E Fellows Green 12. Verbal Report from Committee Chairs and Minutes Audit Committee A Silvester Verbal update. Subject Lead Attachment Health and Wellbeing Board I Richens Salmon Verbal update and minutes from 25 September 2019 and 8 January 2020 meetings. Primary Care Commissioning Committee M Geary Lilac Verbal update and minutes from 29 October 2019. Quality and Safeguarding Committee K Atkinson Verbal Verbal update. -

Review of Prescribing, Supply & Administration of Medicines

REVIEW OF PRESCRIBING, SUPPLY & ADMINISTRATION OF MEDICINES Final Report March 1999 Further copies of this report are available from: NHS Responseline 0541 555 455 REVIEW OF PRESCRIBING, SUPPLY & ADMINISTRATION OF MEDICINES Final Report March 1999 Rt Hon Frank Dobson MP Secretary of State for Health Room 407, Richmond House 79 Whitehall London SW1A 2NS Dear Secretary of State I have pleasure in submitting to you the second Report of the Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines The Review Team members have considered carefully the extensive evidence that was submitted during the period of consultation. It is inevitable that we could not produce recommendations which would meet all the aspirations expressed to us, while at the same time meeting your requirements for a robust framework for an extension of prescribing which safeguards patient safety. The team believes, however, that its proposals, if implemented, will provide a secure means of increasing the range of health professionals who are authorized to prescribe. This will improve services to patients, make better use of the skills of professional staff and thus make a significant contribution to the modernization of the Health Service. I would like to place on record my grateful thanks to the chairs of the Review Team sub-groups and other Team members, all of whom have given generously of their time and energy to this work while maintaining their busy professional responsibilities. Our discussions have been forthright, in considering the complex issues before us, but have always been constructive and good humoured. The Review Team members join me in expressing our thanks to Donna Sidonio, who led most of the work of the secretariat, and all her colleagues from the Department of Health and the Welsh, Scottish and Northern Ireland Offices. -

AI in Health Rapport.Cdr

Market Report AI in Health in the United Kingdom An overview for SME’s and Research Institutes on the trends, challenges and opportunities for AI applications in the British Healthcare sector. Colofon This market report has been written by Hassan Chaudhury from Vita Healthcare Solutions as commissioned by the Netherlands Innovation Network UK and Netherlands Business Support Office Manchester. Author Hassan Chaudhury, Vita Healthcare Solutions Editors Marjolein Bouwers, Chief Innovation Officer, Netherlands Innovation Network UK Els Steiger, Chief Representative, Netherlands Business Support Office Manchester Design NBSO Manchester Contact details Netherlands Innovation Network UK NBSO Manchester Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 11th Floor Centurion House 38 Hyde Park Gate 129 Deansgate South Kensington Manchester London M3 3WR SW7 5DP T: +44 (0) 207 590 3296 T: +44 (0) 161 834 6033 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an automated database, or made public, in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, printouts, copies or in any way whatsoever, without prior written permission from the publisher. © 2021, Netherlands Innovation Network UK & Netherlands Business Support Office Manchester NBSO Manchester Contents Introduction 2 Foreword by author 3 1. Why the UK in AI for health? 4 2. Context 7 2.1 Government policy and ambitions 8 2.2 The Industrial Challenge, Grand Challenges and Challenge Fund 8 2.3 The NHS - not a single national -

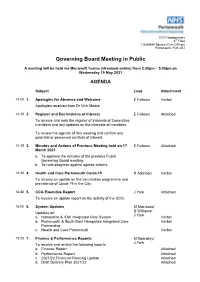

Governing Board Meeting in Public

CCG Headquarters 4th Floor 1 Guildhall Square (Civic Offices) Portsmouth PO1 2GJ Governing Board Meeting in Public A meeting will be held via Microsoft Teams (streamed online) from 2.00pm – 5.00pm on Wednesday 19 May 2021 AGENDA Subject Lead Attachment 14:00 1. Apologies for Absence and Welcome E Fellows Verbal Apologies received from Dr Nick Moore 14:10 2. Register and Declarations of Interest E Fellows Attached To receive and note the register of interests of Committee members and any updates on the interests of members. To review the agenda of this meeting and confirm any potential or perceived conflicts of interest. 14:15 3. Minutes and Actions of Previous Meeting held on 17 E Fellows Attached March 2021 a. To approve the minutes of the previous Public Governing Board meeting. b. To note progress against agreed actions. 14:30 4. Health and Care Portsmouth Covid-19 H Atkinson Verbal To receive an update on the vaccination programme and prevalence of Covid-19 in the City. 14:45 5. CCG Executive Report J York Attached To receive an update report on the activity of the CCG. 15:00 6. System Updates M MacIsaac/ D Williams/ Updates on: J York a. Hampshire & IOW Integrated Care System Verbal b. Portsmouth & South East Hampshire Integrated Care Verbal Partnership c. Health and Care Portsmouth Verbal 15:20 7. Finance & Performance Reports M Spandley/ J York To receive and review the following reports: a. Finance Report Attached b. Performance Report Attached c. 2021/22 Financial Planning Update Attached d. Draft Delivery Plan 2021/22 Attached Subject Lead Attachment 15:45 8. -

Audit Committee Ambulance Services in Wales Inquiry July 2009

Audit Committee Ambulance Services in Wales Inquiry July 2009 The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this report can be found on the National Assembly’s website www.assemblywales.org Further hard copies of this document can be obtained from: Audit Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 029 2089 8617 Fax: 029 2089 8021 Email: [email protected] National Assembly for Wales Audit Committee Ambulance Services in Wales Inquiry July 2009 Ambulance Services in Wales Inquiry Contents Chair’s Foreword 4 Introduction 5 The eight minute standard 8 Rapid Response Vehicles 9 Transport of patients by other emergency services 11 Intelligent targets 12 Advanced Paramedic Practitioners 13 Handovers 15 Data terminals 16 Handover targets 17 Making best use of resources 18 Ambulance officers 19 Restocking 21 Sharing best practice 21 Addressing geographical variations 22 Staffing levels at emergency departments 23 The staff experience 24 WAST financial position 25 Re-organisation of the NHS 26 1 Annexes Audit Committee Record of Proceedings 21 January Annex 1 2009 Audit Committee Record of Proceedings 11 March Annex 2 2009 Audit Committee Record of Proceedings 30 April 2009 Annex 3 Audit Committee Record of Proceedings 4 June 2009 Annex 4 Audit Committee Record of Proceedings 18 June Annex 5 2009 AC(3) 08-09 (p1) Unison – Ambulance Services in Annex 6 Wales -

North Somerset Clinical Commissioning Group Operational Plan for 2014/15 – 2015/16

North Somerset Clinical Commissioning Group Operational plan for 2014/15 – 2015/16 North Somerset CCG Operational Plan for 2014/15 – 2015/16) 1 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Our vision ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 National Context ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Our Population ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 Population growth predictions ......................................................................................................................... 11 Inequalities ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 The Health of the population ........................................................................................................................... 13 Improving Outcomes and Reducing Health Inequalities .....................................................................................