Transformative Leadership and Its Development in Public Service Reform in Kenya Gerald Paul Regier Walden University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Ranking Rapid Baseline Survey on the Status of Gender Equality in Kenyan Political Parties

GENDER RANKING RAPID BASELINE SURVEY ON THE STATUS OF GENDER EQUALITY IN KENYAN POLITICAL PARTIES (ZERO DRAFT) © APRIL 2014 1 | P a g e Table of Contents 1 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 4 2 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Objectives ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Why Gender Ranking of Political Parties? .................................................................. 7 3 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 7 4 BARRIERS TO WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION ........................................................ 17 4.1 The Situation of Women in Politics ............................................................................. 17 4.2 Evaluations on the Internal and External Barriers to Women’s Political Participation ............................................................................................................................ 18 5 METHODOLGY ...................................................................................................................... 19 5.1 Survey Design ............................................................................................................... 19 5.2 Limitations of the Survey ............................................................................................ -

Vnr Report for Kenya.Pdf

qwertylzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjkl zxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnm qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwIMPLEMEMENTATION OF THE AGENDA 2030 ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerFOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN KENYA t June, 2017 yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz xcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopai sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf MINISTRY OF DEVOLUTION AND PLANNING IMPLEMEMENTATION OF THE AGENDA 2030 FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN KENYA June, 2017 ii Ministry of Devolution and Planning P.O Box 30005-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel:+254-02-2252299 Fax: +254-02-218475 Email:[email protected] Website:www.devolution planning.go.ke iii iv v LIST OF ACRONYMS ASAL Arid and Semi-Arid Lands ASTII Africa Science Innovation Indicators ATMs Automated Teller Machines CIDPs County Integrated Development Programme COG Council of Governors COTU Organization of Trade Unions CSO Civil Society Organizations DaO Delivering as One DLP Digital Literacy Programme DRR Disaster Risk Reduction EAC East Africa Community EASA East Africa School of Aviation ECDE Early Childhood Development Education EDE End Drought Emergencies EmONC Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care FBO Faith Based Organization FGM/C Female Genital Mutilation/Cut FKE Federation of Kenya Employers FPE Free Primary Education GBV Gender -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

The Mdgs and Sauri Millennium Village in Kenya

An Island of Success in a Sea of Failure? The MDGs and Sauri Millennium Village in Kenya Amrik Kalsi MBA: Master of Business Administration MSc: Master of Science in Management and Organisational Development MA: Master of Arts A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Social Science Abstract For a number of decades, foreign aid-supported poverty reduction and development concepts, and policies and programmes developed by development agencies and experts implemented since the 1950s, have produced limited short-term and sometimes contradictory results in Kenya. In response to this problem in 2000, the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) was in many respects a tremendous achievement, gaining unprecedented international support. The MDGs model has since become the policy of choice to reduce poverty and hunger in developing countries by half between 2000 and 2015, being implemented by the Millennium Village Project (MVP) ‘Big-Push’ model, seemingly designed as a ‘bottom-up’ approach. Poverty reduction and sustainable development are key priorities for the Kenyan government and the Kenya Vision 2030 blueprint project. The MDGs process, enacted as the Millennium Village Project (MVP) in Kenya for poverty reduction, is now at the centre of intense debate within Kenya. It is widely recognised that foreign aid maintained MVP and sustainable development through the UN and local efforts, especially in their present form, have largely failed to address poverty in Kenya. Furthermore, not enough was known about the achievements of the MVP model in real- world situations when the MVP model interventions were applied in the Sauri village. -

Kenya Sector Plan for Science, Technology and Innovation

REPUBLIC OF KENYA SECTOR PLAN FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION 2013-2017 KENYA Revitalizing and Harnessing Science, Technology and Innovation for Kenya’s Prosperity and Global Competitiveness i FOREWORD The government recognizes the key role played by Science, Technology and Innovation (ST&I) in wealth creation and building human capital required for the transition to a knowledge driven economy. Vision 2030 proposes to intensify the application of ST&I to raise productivity and efficiency levels across the three pillars of national development. As a result, the Government is implementing the ST&I policy framework through the identification, acquisition, transfer, diffusion and application of relevant ST&I knowledge in all sectors of the economy. The first Medium Term Plan (MTP) 2008-2012 was developed based on the challenges identified in vision 2030 and other policy documents. It was implemented through a coordinated action plan within the context of economic, social and political pillars of the economy. The development of capacities of the national innovation system has been fast tracked to ensure the competitiveness in the international technology market, based on the targeted programmes from the identified sectoral areas. However, more need to be done and as a result, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology and its stakeholders have developed the second MTP for 2013-2017 for the Science, Technology and Innovation sector. This second MTP (2013-2017) proposes more strategic and bold programmes to address the persisting macroeconomic and social-economic challenges, facing the country. The objective of the second MTP is to achieve the transformation to a knowledge based economy that integrates ST&I in national production processes and create technology platforms essential for the development of products, processes and services in a wide range of sectors. -

Kenya Vision 2030 a Globally Competitive and Prosperous Kenya

Kenya Vision 2030 A Globally Competitive and Prosperous Kenya October 2007 THE NATIONAL ANTHEM Swahili English Ee Mungu nguvu yetu O God of all creation Ilete baraka kwetu Bless this our land and nation Haki iwe ngao na mlinzi Justice be our shield and defender Natukae na undugu May we dwell in unity Amani na uhuru Peace and liberty Raha tupate na ustawi Plenty be found within our borders Amkeni ndugu zetu Let one and all arise Tufanye sote bidii With hearts both strong and true Nasi tujitoe kwa nguvu Service be our earnest endeavour Nchi yetu ya Kenya And our homeland of Kenya Tunayoipenda Heritage of splendour Tuwe tayari kuilinda Firm may we stand to defend Natujenge taifa letu Let all with one accord Ee, ndio wajibu wetu In common bond united Kenya istahili heshima Build this our nation together Tuungane mikono And the glory of Kenya Pamoja kazini The fruit of our labour Kila siku tuwe na shukrani Fill every heart with thanksgiving FOREWORD The unveiling of Kenya Vision 2030 marks an important milestone in our country’s development as it comes soon after the successful implementation of the “Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation” (ERS) over the period 2003 to-date. The Kenya economy has now recovered from the slow growth rate of 0.6 percent in 2002 to a projected growth of over 7 percent in 2007. Indeed, the last five years represent the best phase of sustained economic growth in our country in all sectors of our economy notably; agriculture, tourism, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade and telecommunications as well as the social Sectors. -

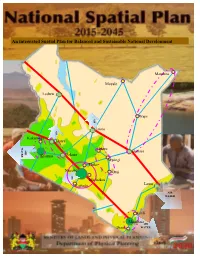

National-Spatial-Plan

An integrated Spatial Plan for Balanced and Sustainable National Development Mandera Moyale Lodwar Wajir AIR AIR Isiolo Kakamega Eldoret WATER AIR Meru Garissa Nakuru Kisumu Mwingi Thika Nairobi Kitui AIR Machakos Kajiado Lamu AIR WATER Kilifi Mombasa AIR Diani WATER APPROVAL CERTIFIED Director of Physical Planning DATE________________________________________________________________________ APPROVED Cabinet Secretary for Lands and Physical Planning DATE_______________________________________________________________________ APPROVED PLAN NO.____________________________________________________ National Spatial Plan, 2015-2045 FOREWORD This National Spatial Plan has been prepared by the National Department of Physical Planning, in the Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning within its mandate of preparing national policies on physical planning. This is an important milestone not only for the Ministry but also for the country having been identified as a flagship project under Kenya Vision 2030. The Plan is timely coming at a time when the country is involved in many initiatives to transform into a globally competitive and prosperous nation. The approval of the National Spatial Plan marks an important landmark in our country‟s development agenda. The Plan details the national spatial vision that will guide the long term spatial development of the country for a period of 30 years. It covers the entire territory of Kenya and defines the general trend and direction of spatial development for the country. It aims at achieving an organized, integrated, sustainable and balanced development of the country, hence informing the future use and distribution of activities by providing a framework for better national organization and linkages between different activities within the national space. Land as we all know is inelastic yet it has many competing land uses. -

Health Policies in Kenya and the New Constitution for Vision 2030

International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology Vol. 2 No. 1; January 2015 HEALTH POLICIES IN KENYA AND THE NEW CONSTITUTION FOR VISION 2030 Agnes W. Kibui, PhD. Senior Lecturer,University of Nairobi, School of Education. Ruth K. Mugo, PhD. Tutorial Fellow, University of Nairobi, School of Education. Grace Nyaga, Senior Lecturer, University of Nairobi, School of Education. Ngesu L. M, PhD. Senior Lecturer, University of Nairobi, School of Education. Mwaniki I. N, PhD. Senior Lecturer, University of Nairobi, College of Humanities and Social Science. Bernard Mwaniki, M.A. Student in Development Studies, St. Pauls University. Abstract Promoting global health ensures progress in basic humanitarian values in saving and improving lives. In recent years, improving global health has proven its advanced value in promoting security and constructive cooperation between countries. A strategic and long-term global health policy helps countries in advancing their core interests in establishing lasting collaborations that save and improve lives of millions globally. This policy helps in creating an environment that enables countries to possess their goals and programs where assessment, cost-effectiveness, and responsibility assume imperative roles. Health challenges are more acute in sub-Saharan Africa compared to other developed nations. These challenges are embedded in a broader context of poverty, poorly developed infrastructure, politically instigated conflicts and disappointingly managed governmental institutions. The sub-Saharan Africa region remains a target of global public health policies and intercessions. Fighting against AIDS, TB, and Malaria, for example, has, in the last decade, spurred an exceptional mobilization of resources to Africa. The Kenya health policies give directions to ensure considerable developments in the position of health in the country. -

Vision 2030 Flagship Projects Progress Report November

VISION 2030 FLAGSHIP PROJECTS PROGRESS REPORT NOVEMBER 2014 i Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 2 1.0 IMPLEMENTATION STATUS ....................................................................................................................... 2 ENABLERS & MACRO ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 INFRASTRUCTURE ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.1 ROAD ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.2 LAMU PORT SOUTH-SUDAN-ETHIOPIA TRANSPORT (LAPSSET) CORRIDOR ................................................ 6 1.1.3 AIRPORTS .................................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1.4 SEAPORTS ............................................................................................................................................... 13 1.1.5 RAIL ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 1.1.6 ENERGY .................................................................................................................................................. -

Stakeholder Mapping Report

Kenya Education Sector Stakeholders A REPORT SUBMITTED TO PAL NETWORK January 2021 Education Policy Scan in response to the Basic Education Curriculum Framework Principles 3 Contents 1.0 Introduction �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �4 1.1 Overall goal of the Policy Dialogue ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 1.2 APD objectives ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 4 2.0 Key Education Stakeholders � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �5 2.1. Research Institutions . 5 2.2 Teacher Training Institutions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 2.3 Government and associated Semi-Autonomous Government Agencies ���������������������������������������������������������� 5 2.4 Universities �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 2.5 Teachers ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 8 2.6 Unions -

Kenya SIGI 2019 Category Medium SIGI Value 2019 35%

Country Kenya SIGI 2019 Category Medium SIGI Value 2019 35% Discrimination in the family 50% Legal framework on child marriage 25% Percentage of girls under 18 married 13% Legal framework on household responsibilities 50% Proportion of the population declaring that children will suffer if mothers are working outside home for a pay - Female to male ratio of time spent on unpaid care work 2.2 Legal framework on inheritance 75% Legal framework on divorce 50% Restricted physical integrity 29% Legal framework on violence against women 50% Proportion of the female population justifying domestic violence 42% Prevalence of domestic violence against women (lifetime) 39% Legal framework on female genital mutilation (FGM) 25% Share of women who think FGM should continue 6% Share of women who have undergone FGM 21% Sex ratio at birth (natural =105) 105 Legal framework on reproductive rights 75% Female population with unmet needs for family planning 16% Restricted access to productive and financial resources 42% Legal framework on working rights 25% Proportion of the population declaring this is not acceptable for a woman in their family to work outside home for a pay 17% Share of managers (male) 90% Legal framework on access to non-land assets 50% Share of house owners (male) 82% Legal framework on access to land assets 50% Share of agricultural land holders (male) - Legal framework on access to financial services 25% Share of account holders (male) 58% Restricted civil liberties 17% Legal framework on civil rights 0% Legal framework on freedom of movement 0% Percentage of women in the total number of persons not feeling safe walking alone at night 58% Legal framework on political participation 25% Share of the population that believes men are better political leaders than women - Percentage of male MP’s 78% Legal framework on access to justice 25% Share of women declaring lack of confidence in the justice system 48% Note: Higher values indicate higher inequality. -

An Analysis of Kenya Vision 2030'S Efforts Towards

AN ANALYSIS OF KENYA VISION 2030’S EFFORTS TOWARDS ACHIEVING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL 10 Reducing Inequality Within Country Brian Sanare Sempele, 647367 Joseph Kimani Njuguna IRL 6902-A, Thesis Summer 2017 KENYA VISION 2030 AND INEQUALITY DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my own original work, and to the best of my knowledge has not been presented or published in any other institution. All materials obtained from other sources are duly acknowledged. Signed: _______________________________ Date: _______________________ Brian Sanare Sempele- ID 647367 Student This thesis has been presented for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor. Signed: _______________________________ Date: _______________________ Mr Joseph Kimani Njuguna Supervisor Signed: _______________________________ Date: _______________________ Dr Tom L.S Onditi Dean, School of Humanities and Social Sciences i KENYA VISION 2030 AND INEQUALITY ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge the professional guidance of my supervisor, Mr Joseph Kimani Njuguna. His direction, integrity, and experienced insights steered me in the direction needed to complete this mammoth task. I would also like to thank the USIU-Africa library and faculty, for consistently having their time and resources available when needed. I wish to appreciate the incredible support of my partner in life Kay, my precious daughter Elsa, and my loving sister Lavender, all of whom supported and encouraged me through the difficult and sometimes inconvenient writing process. ii KENYA VISION 2030 AND INEQUALITY DEDICATION I dedicate this work to the millions of Kenyans that strive daily to better their lives, despite the many economic and systemic challenges they encounter. iii KENYA VISION 2030 AND INEQUALITY ABSTRACT Kenya has been experiencing significant economic growth over the last few decades.