Negative Reinforcement Learning Is Affected in Substance Dependence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Substance Abuse and Dependence

9 Substance Abuse and Dependence CHAPTER CHAPTER OUTLINE CLASSIFICATION OF SUBSTANCE-RELATED THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES 310–316 Residential Approaches DISORDERS 291–296 Biological Perspectives Psychodynamic Approaches Substance Abuse and Dependence Learning Perspectives Behavioral Approaches Addiction and Other Forms of Compulsive Cognitive Perspectives Relapse-Prevention Training Behavior Psychodynamic Perspectives SUMMING UP 325–326 Racial and Ethnic Differences in Substance Sociocultural Perspectives Use Disorders TREATMENT OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Pathways to Drug Dependence AND DEPENDENCE 316–325 DRUGS OF ABUSE 296–310 Biological Approaches Depressants Culturally Sensitive Treatment Stimulants of Alcoholism Hallucinogens Nonprofessional Support Groups TRUTH or FICTION T❑ F❑ Heroin accounts for more deaths “Nothing and Nobody Comes Before than any other drug. (p. 291) T❑ F❑ You cannot be psychologically My Coke” dependent on a drug without also being She had just caught me with cocaine again after I had managed to convince her that physically dependent on it. (p. 295) I hadn’t used in over a month. Of course I had been tooting (snorting) almost every T❑ F❑ More teenagers and young adults die day, but I had managed to cover my tracks a little better than usual. So she said to from alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents me that I was going to have to make a choice—either cocaine or her. Before she than from any other cause. (p. 297) finished the sentence, I knew what was coming, so I told her to think carefully about what she was going to say. It was clear to me that there wasn’t a choice. I love my T❑ F❑ It is safe to let someone who has wife, but I’m not going to choose anything over cocaine. -

GABA Systems, Benzodiazepines, and Substance Dependence

Robert J. Malcolm GABA Systems, Benzodiazepines, and Substance Dependence Robert J. Malcolm, M.D. Alterations in the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor complex and GABA neurotransmission influence the reinforcing and intoxicating effects of alcohol and benzodiazepines. Chronic modulation of the GABAA-benzodiazepine receptor complex plays a major role in central nervous system dysregulation during alcohol abstinence. Withdrawal symptoms stem in part from a decreased GABAergic inhibitory function and an increase in glutamatergic excitatory function. GABAA recep- tors play a role in both reward and withdrawal phenomena from alcohol and sedative-hypnotics. Although less well understood, GABAB receptor complexes appear to play a role in inhibition of moti- vation and diminish relapse potential to reinforcing drugs. Evidence suggests that long-term alcohol use and concomitant serial withdrawals permanently alter GABAergic function, down-regulate ben- zodiazepine binding sites, and in preclinical models lead to cell death. Benzodiazepines have substan- tial drawbacks in the treatment of substance use–related disorders that include interactions with alco- hol, rebound effects, alcohol priming, and the risk of supplanting alcohol dependency with addiction to both alcohol and benzodiazepines. Polysubstance-dependent individuals frequently self-medicate with benzodiazepines. Selective GABA agents with novel mechanisms of action have anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and reward inhibition profiles that have potential in treating substance use and with- drawal and enhancing relapse prevention with less liability than benzodiazepines. The GABAB receptor agonist baclofen has promise in relapse prevention in a number of substance dependence dis- orders. The GABAA and GABAB pump reuptake inhibitor tiagabine has potential for managing alcohol and sedative-hypnotic withdrawal and also possibly a role in relapse prevention. -

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs

Barriers and Solutions to Addressing Tobacco Dependence in Addiction Treatment Programs Douglas M. Ziedonis, M.D., M.P.H.; Joseph Guydish, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Jill Williams, M.D.; Marc Steinberg, Ph.D.; and Jonathan Foulds, Ph.D. Despite the high prevalence of tobacco use among people with substance use disorders, tobacco dependence is often overlooked in addiction treatment programs. Several studies and a meta-analytic review have concluded that patients who receive tobacco dependence treatment during addiction treatment have better overall substance abuse treatment outcomes compared with those who do not. Barriers that contribute to the lack of attention given to this important problem include staff attitudes about and use of tobacco, lack of adequate staff training to address tobacco use, unfounded fears among treatment staff and administration regarding tobacco policies, and limited tobacco dependence treatment resources. Specific clinical-, program-, and system-level changes are recommended to fully address the problem of tobacco use among alcohol and other drug abuse patients. KEY WORDS: Alcohol and tobacco; alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use, abuse, dependence; addiction care; tobacco dependence; smoking; secondhand smoke; nicotine; nicotine replacement; tobacco dependence screening; tobacco dependence treatment; treatment facility-based prevention; co-treatment; treatment issues; treatment barriers; treatment provider characteristics; treatment staff; staff training; AODD counselor; client counselor interaction; smoking cessation; Tobacco Dependence Program at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey obacco dependence is one of to the other. The common genetic vul stance use was considered a potential the most common substance use nerability may be located on chromo trigger for the primary addiction. -

BENZODIAZEPINE DEPENDENCE & PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AMONG HEROIN USERS in SYDNEY Joanne Ross & Shane Darke. NDARC Technical Re

BENZODIAZEPINE DEPENDENCE & PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AMONG HEROIN USERS IN SYDNEY Joanne Ross & Shane Darke. NDARC Technical Report No. 50 Technical Report No. 50 BENZODIAZEPINE DEPENDENCE AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AMONG HEROIN USERS IN SYDNEY Joanne Ross & Shane Darke National Drug & Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales, Sydney. ISBN: 0 947229 80 9 NDARC 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..............................................................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................ viivii 1.0 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Study Aims................................................................................................................................................................................................................................2 2.0 METHOD.....................................................................................................................3 2.1 Procedure..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 2.2 Structured Interview..............................................................................................................................................................................3 -

MARIJUANA and SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a Historical Perspective and DSM-5 Overview

MARIJUANA AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER, Part 1: a historical perspective and DSM-5 overview Introduction Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug in the Western world and the third most commonly used recreational drug after alcohol and tobacco. According to the World Health Organization, it also is the illicit substance most widely cultivated, trafficked, and used. Although the long-term clinical outcome of marijuana use disorder may be less severe than other commonly used substances, it is by no means a "safe" drug. Sustained marijuana use can have negative impacts on the brain as well as the body. Studies have indicated a link between regular marijuana use and schizophrenia as well as a demonstrated relationship between marijuana use and a higher incidence of lung cancer. Although there are no pharmacological treatments available with a proven impact on marijuana use disorder, there are several types of behavior therapy that may be effective in treating this disorder. Worldwide Use Of Marijuana For a number of years, the United Nations has been compiling annual surveys of worldwide drug use, including cannabis. Reflecting the difficulties and uncertainties associated with developing estimates of the number of people who use drugs (such as the quality of the data gathered and the methodologies used to sample populations), the latest United Nations estimates are presented in ranges, reflecting the lower and upper estimates indicated through the array of surveys ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com 1 available. In their 2012 report (covering 2010), the United Nations estimated that between 119.4 and 224.5 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 had used cannabis in the past year, representing between 2.6% and 5.0% of the world’s population.22 In 2014, approximately 22.2 million people ages 12 and up reported using marijuana during the past month. -

Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002 by Jennifer C

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report July 2005, NCJ 209588 Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002 By Jennifer C. Karberg and Doris J. James Highlights BJS Statisticians In 2002, 68% of jail inmates reported symptoms in the year before their admission to jail that met substance dependence or abuse criteria In 2002 more than two-thirds of jail Percent of jail inmates $ 52% of female jail inmates inmates were found to be dependent Alcohol were found to be dependent on on or to abuse alcohol or drugs, based Alcohol Drugs or drugs alcohol or drugs, compared to on data from the Survey of Inmates in Any dependence or abuse 47% 53% 68% Dependence 23 36 45 44% of male inmates. Local Jails, 2002. Two in five inmates Abuse only 24 18 23 were dependent on alcohol or drugs, No dependence or abuse 53 47 32 while nearly 1 in 4 abused alcohol or drugs, but were not dependent on 3 in 4 convicted property or drug offenders met substance dependence them. Estimates of substance depend- or abuse criteria, compared to 2 in 3 violent or public-order offenders Percent of convicted inmates ence or abuse were based on criteria Use at Dependence $ Half of all convicted jail inmates specified in the Diagnostic and Statisti- Offense offense or abuse were under the influence of drugs cal Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth All inmates 50% 71% or alcohol at the time of offense. Violent 47 67 edition (DSM-IV). Property 47 73 Drug 52 73 $ In 2002, 16% of convicted jail Jail inmates who met the criteria for Public-order* 37 66 inmates said they committed their substance dependence or abuse (70%) *Excludes DWI/DUI. -

Current Concepts on Drug Abuse and Dependence Daniela Luiza Baconi Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Daniela [email protected]

Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 4 2015 Current Concepts on Drug Abuse and Dependence Daniela Luiza Baconi Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, [email protected] Anne-Marie Ciobanu Carol Davila University of Pharmacy and Medicine Ana Maria Vlăsceanu Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Oana Denisa Cobani St. John Emergency Hospital Carolina Negrei Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Baconi, Daniela Luiza; Ciobanu, Anne-Marie; Vlăsceanu, Ana Maria; Cobani, Oana Denisa; Negrei, Carolina; and Bălălău, Cristian (2015) "Current Concepts on Drug Abuse and Dependence," Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol2/iss1/4 This Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Current Concepts on Drug Abuse and Dependence Authors Daniela Luiza Baconi, Anne-Marie Ciobanu, Ana Maria Vlăsceanu, Oana Denisa Cobani, Carolina Negrei, and Cristian Bălălău This review article is available in Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol2/iss1/4 JMMS 2015, 2(1): 18- 33. REVIEW Current concepts on drug abuse and dependence Daniela Luiza Baconi1, Anne-Marie Ciobanu2, Ana Maria Vlăsceanu1, Oana Denisa Cobani3, Carolina Negrei1, Cristian Bălălău4 1 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Toxicology 2 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medicines Control 3 St. -

Coding Guidline

Substance use disorders ICD-10-CM Clinical overview Definitions and overview American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical NOTE: The purpose of this guideline is to address medical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5): record documentation and diagnosis coding. In-depth . Substance use disorders: A cluster of cognitive, diagnostic criteria are outside the scope of this document. behavioral and physiological symptoms indicating that Healthcare providers must consult the DSM-5 manual -which the individual continues using the substance despite is the gold standard - for detailed information related to significant substance-related problems. diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders. World Health Organization: Causes . Substance abuse: The harmful or hazardous use of The exact cause of substance use disorder is not known. psychoactive substances, including alcohol and illicit Some of the contributing factors include: drugs. Genetic . Environmental . Substance dependence: A cluster of behavioral, predisposition stressors cognitive and physiological phenomena that develop . Peer pressure . Trauma after repeated substance use and that typically include a . Emotional stress . Anxiety, strong desire to take the drug, difficulties in controlling . Family history of depression or its use, persisting in its use despite harmful substance use other mental disorders health disorders consequences, a higher priority given to drug use than (see next section) to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance and sometimes a physical withdrawal state. Substance use disorders and mental health problems The most common drug classifications associated with Mental health problems and substance use disorders substance use disorders are: sometimes coexist for the following reasons: . Alcohol . Cannabis (marijuana) . Mental health problems and substance use disorders . -

Marijuana Dependendence and Its Treatment

4 • A D D I C T I O N S C I E N C E & C L I N I C A L P R A C T I C E — D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 7 Marijuana Dependence and Its Treatment he prevalence of marijuana abuse and dependence disorders has been increasing among adults and adolescents in the TUnited States. This paper reviews the problems associated with marijuana use, including unique characteristics of mari- juana dependence, and the results of laboratory research and treatment trials to date. It also discusses limitations of current knowledge and potential areas for advancing research and clinical intervention. Alan J. Budney, Ph.D.1 arijuana remains the most widely used illicit substance in the United 2 Roger Roffman, D.S.W. States and Europe (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Robert S. Stephens, Ph.D.3 Drug Addiction, 2006; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Denise Walker, Ph.D.2 M 1University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Administration (SAMHSA), 2007). Although some people question the concept Little Rock, Arkansas of marijuana dependence or addiction, diagnostic, epidemiological, laboratory, 2 University of Washington and clinical studies clearly indicate that the condition exists, is important, and Seattle, Washington causes harm (Budney, 2006; Budney and Hughes, 2006; Copeland, 2004; Roffman 3 Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and Stephens, 2006). Marijuana dependence as experienced in clinical popula- Blacksburg, Virginia tions appears very similar to other substance dependence disorders, although it is likely to be less severe. Adults seeking treatment for marijuana abuse or depend- ence average more than 10 years of near-daily use and more than six serious attempts at quitting (Budney, 2006; Copeland et al., 2001; Stephens et al., 2002). -

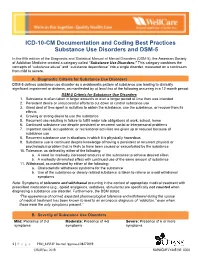

ICD-10-CM Documentation and Coding Best Practices Substance Use Disorders and DSM-5

ICD-10-CM Documentation and Coding Best Practices Substance Use Disorders and DSM-5 In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the American Society of Addiction Medicine created a category called “Substance Use Disorders.” This category combines the concepts of “substance abuse” and “substance dependence” into a single disorder, measured on a continuum from mild to severe. A. Diagnostic Criteria for Substance Use Disorders DSM-5 defines substance use disorder as a problematic pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following occurring in a 12-month period: DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Disorders 1. Substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than was intended 2. Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use 3. Great deal of time spent in activities to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects 4. Craving or strong desire to use the substance 5. Recurrent use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, home 6. Continued substance use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems 7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use 8. Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous 9. Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance 10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following: a. -

Addiction Professionals' Attitudes Regarding Treatment of Nicotine Dependence

Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 5 January 2002 Addiction Professionals' Attitudes Regarding Treatment of Nicotine Dependence Baljit S. Gill M.D. Eastern Virginia Medical School; Substance Abuse Treatment Program, VA Medical Center, Hampton, VA; Psychiatry Residency Program, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA Dwayne L. Bennett M.D. Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA Mohammad Abu-Salha M.D. Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA Lisa Fore-Arcand Ed.D. Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jeffjpsychiatry Part of the Psychiatry Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Gill, Baljit S. M.D.; Bennett, Dwayne L. M.D.; Abu-Salha, Mohammad M.D.; and Fore-Arcand, Lisa Ed.D. (2002) "Addiction Professionals' Attitudes Regarding Treatment of Nicotine Dependence," Jefferson Journal of Psychiatry: Vol. 17 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29046/JJP.017.1.004 Available at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jeffjpsychiatry/vol17/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. -

Dsm 5 Substance Use Disorders

DSM 5 SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Ronald W. Kanwischer LCPC, CADC Professor Emeritus Department of Psychiatry SIU School of Medicine I have no financial relationships to disclose with regard to this presentation. This talk is free of commercial bias. What’s in a Name? The very naming of something creates new realities, new situations, and often new problems. Thomas D. Watts What’s In a Name? “An Odious Disease” Dr. Benjamin Rush, 1784 The word “alcohol” didn’t come into use until the eighteenth century and was used to designate the intoxicating ingredient in liquor. “alcoholism” was first used in 1849 by Dr. Magnus Huss to describe chronic intoxication with physical and social pathology A century later the word “alcoholic” was common in the United States Slang and Professional Language used to describe a problem with alcohol and the problem drinker Drunkard Jellinek’s Disease Inebriety/Inebriates Problem Drinker Tipplers Alcoholic Intemperance Problematic alcohol use Dipsomania (thirst frenzy) Deviant drinker Drunkard Excessive drinking Barrel fever Addiction (from the Latin, Alcoholism “to adore”, to surrender oneself) The Evolution of the Concepts of Addiction The history of diagnoses in the DSM reflects the evolving concept of addiction In the DSM the diagnostic decision is binary, they either meet the specific criteria or they do not. In reality, symptoms exist more as if on a continuum. The Evolution of the Concepts of Addiction In the first edition of the DSM in the 1950’s, alcoholism and drug addiction were grouped with “sociopathic personality disturbances” Signs and symptoms were not described, but instead the idea that addiction came from an “underlying brain or personality disorder”.