The Ultimate Detectors for Cmb Measurements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monolayer Graphene Bolometer As a Sensitive Far-IR Detector Boris S

Monolayer graphene bolometer as a sensitive far-IR detector Boris S. Karasik*a, Christopher B. McKitterickb, Daniel E. Proberb aJet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Dr., Pasadena, CA USA 91109; bDepts. of Phys. and Appl. Phys., Yale University, 15 Prospect St., BCT 417, New Haven, CT USA 06520 ABSTRACT In this paper we give a detailed analysis of the expected sensitivity and operating conditions in the power detection mode of a hot-electron bolometer (HEB) made from a few µm2 of monolayer graphene (MLG) flake which can be embedded into either a planar antenna or waveguide circuit via NbN (or NbTiN) superconducting contacts with critical temperature ~ 14 K. Recent data on the strength of the electron-phonon coupling are used in the present analysis and the contribution of the readout noise to the Noise Equivalent Power (NEP) is explicitly computed. The readout scheme utilizes Johnson Noise Thermometry (JNT) allowing for Frequency-Domain Multiplexing (FDM) using narrowband filter coupling of the HEBs. In general, the filter bandwidth and the summing amplifier noise have a significant effect on the overall system sensitivity. The analysis shows that the readout contribution can be reduced to that of the bolometer phonon noise if the detector device is operated at 0.05 K and the JNT signal is read at about 10 GHz where the Johnson noise emitted in equilibrium is substantially reduced. Beside the high sensitivity (NEP < 10-20 W/Hz1/2), this bolometer does not have any hard saturation limit and thus can be used for far-IR sky imaging with arbitrary contrast. -

Pixel-Wise Motion Deblurring of Thermal Videos

Pixel-Wise Motion Deblurring of Thermal Videos Manikandasriram S.R.1, Zixu Zhang1, Ram Vasudevan2, and Matthew Johnson-Roberson3 Robotics Institute1, Mechanical Engineering2, Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering3 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA 48109. fsrmani, zixu, ramv, [email protected] https://fcav.engin.umich.edu/papers/pixelwise-deblurring Abstract—Uncooled microbolometers can enable robots to see in the absence of visible illumination by imaging the “heat” radiated from the scene. Despite this ability to see in the dark, these sensors suffer from significant motion blur. This has limited their application on robotic systems. As described in this paper, this motion blur arises due to the thermal inertia of each pixel. This has meant that traditional motion deblurring techniques, which rely on identifying an appropriate spatial blur kernel to perform spatial deconvolution, are unable to reliably perform motion deblurring on thermal camera images. To address this problem, this paper formulates reversing the effect of thermal inertia at a single pixel as a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) problem which we can solve rapidly using a quadratic programming solver. By leveraging sparsity and a high frame rate, this pixel-wise LASSO formulation is able to recover motion deblurred frames of thermal videos without using any spatial information. To compare its quality against state-of- Fig. 1: An illustration of the proposed motion deblurring algorithm for the-art visible camera based deblurring methods, this paper eval- microbolometers. The top image shows a visible image captured at 30fps with uated the performance of a family of pre-trained object detectors auto exposure. -

Infrared Imaging Video Bolometer with a Double Layer Absorbing Foil

Plasma and Fusion Research: Regular Articles Volume 2, S1052 (2007) Infrared Imaging Video Bolometer with a Double Layer Absorbing Foil Igor V. MIROSHNIKOV, Artem Y. KOSTRYUKOV and Byron J. PETERSON1) St. Petersburg State Technical University, 29 Politechnicheskaya Str., St. Petersburg, 195251, Russia. 1)National Institute for Fusion Science, 322-6 Oroshi-cho, Toki, 509-5292, Japan (Received 30 November 2006 / Accepted 11 August 2007) The object of the present paper is an infrared video bolometer with a bolometer foil consisting of two layers: the first layer is constructed of radiation absorbing blocks and the second layer is a thermal isolating base. The absorbing blocks made of a material with a high photon attenuation coefficient (gold) were spatially separated from each other while the base should be made of a material having high tensile strength and low thermal con- ductance (stainless steel). Such a foil has been manufactured in St. Petersburg and calibratedinNIFSusinga vacuum test chamber and a laser beam as an incident power source. A finite element method (FEM) code was applied to simulate the thermal response of the foil. Simulation results are in good agreement with the experi- mental calibration data. The temperature response of the double layer foil is a factor of two higher than that of a single foil IR video bolometer using the same absorber material and thickness. c 2007 The Japan Society of Plasma Science and Nuclear Fusion Research Keywords: plasma bolometry, infrared imaging bolometer, double layer foil, finite element method simulation DOI: 10.1585/pfr.2.S1052 1. Introduction 2. Double Layer Foil Design and Man- The idea of infrared imaging bolometry is to absorb ufacturing the incident plasma radiation in an ultra thin (1 µm-2.5 µm) The idea of DLF design is shown in Fig. -

Designing of Sensing Element for Bolometer Working at Room Temperature

IOSR Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering (IOSR-JECE) e-ISSN: 2278-2834,p- ISSN: 2278-8735. PP 47-52 www.iosrjournals.org Designing of Sensing Element for Bolometer Working at Room Temperature 1 2 Debalina Panda , Subrat Kumar Pradhan 1 M.Tech Scholar, Dept. of ECE, Centurion University of Technology &Management, Odisha, INDIA 3 Asst. Professor, Dept. of ECE, Centurion University of Technology &Management, Odisha, INDIA Abstract: Bolometer is a highly sensitive thermal detector used for detection of heat or electromagnetic radiation. It has vast applications extending their range to the field of military, medical, astronomy, particle physics and in day-to-day use thus devising it as a significant part of our society. The basic operation principle is that it measures the incident radiation power through absorption resulting a specific change in a measurable quantity. This present work aims at designing of a MEMS based bolometer analysing the variation of thermal conductivity in response to the temperature by using COMSOL Multiphysics®. Here the temperature change occurs due to the incident infrared radiation. The proposed bolometer design is efficient of operating at elevated temperatures (>273 K) and thus can be implemented in a Wheatstone bridge to make it a modifiable detector for better sensitivity. I. Introduction Bolometer is light, rugged, reliable and low cost resistive thermal detectors generally used for low temperature operation. These are radiation power detectors constructed from a material having very small thermal capacity and large thermal coefficient so that the absorbed incident radiation produces a large change in resistance. It consists of an absorptive element connected to a thermal reservoir (or heat sink) and a thermopile attached to it for measurement of temperature as shown in Fig.1. -

Development of Cryogenic Bolometer for Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay in 124Sn

Development of Cryogenic Bolometer for Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay in 124Sn By Vivek Singh PHYS01200804030 Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Mumbai – 400 085 A thesis submitted to the Board of Studies in Physical Sciences In partial fulfillment of requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of HOMI BHABHA NATIONAL INSTITUTE October, 2014 Homi Bhabha National Institute Recommendations of the Viva Voce Board As members of the Viva Voce Board, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Vivek Singh entitled “Development of Cryogenic Bolometer for Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay in 124Sn” and recommend that it may be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy. Chairman - Prof. S. L. Chaplot Date: Guide / Convener - Prof. V. Nanal Date: Co-guide - Prof. V. M. Datar Date: Member - Dr. G. Ravikumar Date: Member - Prof. R. G. Pillay Date: Member - Dr. V. Ganesan Date: Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to HBNI. I/We hereby certify that I/we have read this dissertation prepared under my/our direction and recommend that it may be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. Date: Place: Co-guide Guide ii STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at Homi Bhabha National Institute (HBNI) and is deposited in the Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the HBNI. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. -

Thz Detectors

THz Detectors John Byrd Short Bunches in Accelerators– USPAS, Boston, MA 21-25 June 2010 Overview • Bolometers • Pyroelectric detectors • Diodes • Golay Cell Short Bunches in Accelerators– USPAS, Boston, MA 21-25 June 2010 Bolometers Bolometer: ORIGIN late 19th cent.: from Greek bolē ‘ray of light’ + -meter In 1878 Samuel Pierpont Langley invented the bolometer, a radiant-heat detector that is sensitive to differences in temperature of one hundred- thousandth of a degree Celsius (0.00001 C) . Composed of two thin strips of metal, a Wheatstone bridge, a battery, and a galvanometer (an electrical current measuring device), this instrument enabled him to study solar irradiance (light rays from the sun) far into its infrared region and to measure the intensity of solar radiation at various wavelengths. Short Bunches in Accelerators– USPAS, Boston, MA 21-25 June 2010 Bolometer principle Short Bunches in Accelerators– USPAS, Boston, MA 21-25 June 2010 Far-IR Silicon bolometer • Spectral response: 2-3000 micron • Operating temperature: 4.2-0.3 deg-K • Responds only to AC signal within detector bandwidth (may need a chopper.) Short Bunches in Accelerators– USPAS, Boston, MA 21-25 June 2010 Pyroelectric Detectors • Ferroelectric materials such as TGS or Lithium Tantalate, exhibit a large spontaneous electrical polarisation which has varies with temperature. • Observed as an electrical signal if electrodes are placed on opposite faces of a thin slice of the material to form a capacitor. • Creates a voltage across the capacitor for a high external impedance • Only sensitive to AC signals (I.e. time-varying) • Room temperature operature • Small detector area can give fast thermal response time. -

Physics with Calorimeters

XIII International Conference on Calorimetry in High Energy Physics (CALOR 2008) IOP Publishing Journal of Physics: Conference Series 160 (2009) 012001 doi:10.1088/1742-6596/160/1/012001 Physics with calorimeters Klaus Pretzl Laboratory of High Energy Physics, University Bern, Sidlerstr.5, CH 3012 Bern, Switzerland E-mail: pretzl@lhep,unibe,ch Abstract. Calorimeters played an essential role in the discoveries of new physics, for example neutral currents (Gargamelle), quark and gluon jets (SPEAR, UA2, UA1 and PETRA), W and Z bosons (UA1, UA2), top quark (CDF, D0) and neutrino oscillations (SUPER-KAMIOKANDE, SNO). A large variety of different calorimeters have been developed covering an energy range between several and 1020 eV. This article tries to demonstrate on a few selected examples, such as the early jet searches in hadron-hadron collisions, direct dark matter searches, neutrino-less double beta decay and direct neutrino mass measurements, how the development of these devices has allowed to explore new frontiers in physics. 1. Historical remarks The American Astronomer Samuel Pierpot Langley has 1878 invented the bolometer in order to measure the infrared radiation of celestial objects [1]. His bolometer consisted of two platinum strips one of which was thermally isolated while the other was exposed to radiation. The exposed strip could be heated due to the absorption of electromagnetic radiation and thus would change its resistance. The two strips were connected to two branches of a Wheatstone bridge which allowed to measure the resistance change of the exposed strip. Therefor a bolometer behaves like a true calorimeter which measures the absorbed energy in form of heat. -

Uncooled Detectors for Thermal Imaging Cameras Making the Right Detector Choice

TECHNICAL NOTE Uncooled detectors for thermal imaging cameras Making the right detector choice In the last few years thermal imaging has found its way into many more com- also exists a ferroelectric technology based on Barium Strontium Titanate mercial applications. Most of these applications require a low cost product (BST). with an uncooled detector. These sensors image in the LWIR, or longwave infrared band (7 - 14 μm). Different types of uncooled detectors are available Users of thermal imaging cameras should get the best and most modern tech- on the market. Since the infrared detector is the heart of any thermal imaging nology if they decide to purchase a system for whatever application. The ability camera, it is of the utmost importance that it is of the best possible quality. to see crystal clear pictures through darkness, fog, haze and smoke all depends on the quality of the detector. Understanding the different technologies for Uncooled detectors are made of different and often quite exotic materials uncooled detectors that are currently on the market can help in making the that each have their own benefits. Microbolometer-based detectors are either right choice. made out of Vanadium Oxide (VOx) or Amorphous Silicon (α-Si) while there Thermal imaging: The technology used at that point in time required initially developed for the military that the camera was filled with liquid nitrogen. Thermal imaging is a technology that originated The systems were extremely expensive and the in military applications. Thermal imaging cameras military had a lock on the technology because it was produce a clear image on the darkest of nights. -

Superconducting Transition Edge Sensor Bolometer Arrays for Submillimeter Astronomy

Superconducting Transition Edge Sensor Bolometer Arrays for Submillimeter Astronomy Dominic J. Benford, Christine A. Allen, Alexander S. Kutyrev, S. Harvey Moseley, Richard A. Shafer NASA - Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 685, Greenbelt, MD 20771 James A. Chervenak, Erich N. Grossman, Kent D. Irwin, John M. Martinis, Carl D. Reintsema NIST - Boulder, MS 814.09, Boulder, CO 80303 Abstract Studies of astrophysical emission in the far-infrared and submillimeter will increasingly require large arrays of detectors containing hundreds to thousands of elements. The last few years have seen the increasing from one to a few tens of bolometers on ground-based telescopes. A further jump of this magnitude, to a thousand bolometers, requires a fundamental redesign of the technology of making bolometer arrays. One method of achieving this increase is to design bolometers which can be packed into a rectangular array of near-unity filling factor while Nyquist-sampling the focal plane of the telescope at the operating wavelengths. In this case, the array becomes more nearly analogous to the arrays used in the near-infrared which underwent a substantial growth during the last decade. A multiplexed readout is necessary for this many detectors, and can be developed using SQUIDs such that a 32×32 array of bolometers could be read out using 100 wires rather than the >2000 needed with a brute force expansion of existing arrays. Superconducting transition edge sensors are used as the detectors for these bolometer arrays. We describe a collaborative effort currently underway at NASA/Goddard and NIST to bring about the first astronomically useful arrays of this design, containing tens of bolometers. -

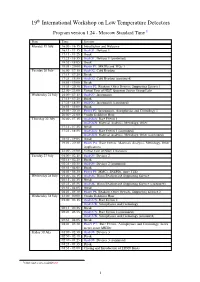

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - Moscow Standard Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 16:00 - 16:15 Introduction and Welcome 16:15 - 17:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O3: Instruments 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 20:00 - 21:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 16:00 - 17:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 17:15 - 17:25 Break 17:25 - 18:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 18:55 - 19:05 Break 19:05 - 20:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 22:00 - 23:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Tuesday 27 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 03:55 - 04:05 Break 04:05 - 05:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Wednesday 28 July 01:00 - 02:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 02:15 - 02:25 Break 02:25 - 03:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting -

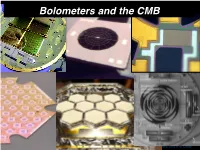

Bolometers and the CMB 1 the CMB Spectrum

BolometersCosmic Microwave and the CMB 08/07/2017 Benson | Bolometers and the CMB 1 The CMB Spectrum 10-13 77 K • CMB is a 2.725 K blackbody Rayleigh -14 • Spectrum peaks at ~150 GHz ) 10 30 K -1 Jeans (RJ) sr -15 • Conveniently peak of CMB “tail” 15 K -1 10 spectrum is near foreground Hz -16 -2 10 minimum (i.e., dust, synchrotron) -17 and atmospheric windows I (W m 10 2.725 K 10-18 • Design detector “bands” to -19 observed within atmospheric 10 100 1000 10000 windows Freq (GHz) • Aim to design instruments where atmospheric loading dominates detector loading 08/07/2017 Benson | Bolometers and the CMB 2 Power on a Detector Power = P (⌫)d⌫ = B(⌫,T) f(⌫) A⌦ d⌫ Z Z • B(ν,T) = Blackbody equation = [ W / m2 sr Hz ] • f(ν) = Frequency response of the detector • AΩ = Throughput (or etendue) of instrument = [m2 sr] 08/07/2017 Benson | Bolometers and the CMB 3 Power on a Detector Power = P (⌫)d⌫ = B(⌫,T) f(⌫) A⌦ d⌫ Z Z • B(ν,T) = Blackbody equation = [ W / m2 sr Hz ] • f(ν) = Frequency response of the detector • AΩ = Throughput (or etendue) of instrument = [m2 sr] 2h⌫3 1 ⌫2 B(⌫,T)= 2k T c2 exp(h⌫/kT ) 1 B c2 RJ − • In RJ limit, x = hv/kT << 1 and exp(x) ~ 1 + x, greatly simplifying the black-body equation. 08/07/2017 Benson | Bolometers and the CMB 4 Power on a Detector Power = P (⌫)d⌫ = B(⌫,T) f(⌫) A⌦ d⌫ Z Z • B(ν,T) = Blackbody equation = [ W / m2 sr Hz ] • f(ν) = Frequency response of the detector • AΩ = Throughput (or etendue) of instrument = [m2 sr] • Can approximate frequency response as a band-width (Δν) times an optical efficiency (η), e.g., -

Optical and Electrical Characterizations of Uncooled Bolometers Based on LSMO Thin Films †

Proceedings Optical and Electrical Characterizations of Uncooled Bolometers Based on LSMO Thin Films † Vanuza M. Nascimento 1,*, Mario E. B. G. N. Silva 1,2, Shuang Liu 1, Leandro Manera 2, Laurence Méchin 1 and Bruno Guillet 1 1 Normandie Univ., UNICAEN, ENSICAEN, CNRS, GREYC, 14000 Caen, France; [email protected] (M.E.B.G.N.S.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (B.G.) 2 School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Campinas, Campinas/SP, 13083-852, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-2-3145-2781 † Presented at the Eurosensors 2017 Conference, Paris, France, 3–6 September 2017. Published: 18 September 2017 Abstract: In this paper the optical and electrical characterization of a 75 × 75 µm2 uncooled bolometers based on free-standing La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 /CaTiO3 (LSMO/CTO) thin films fabricated by micromachining of the silicon substrates is presented. R(T) curves have been compared to electro thermal simulations. Its thermal conductance was measured to be 9 × 10−6 W·K−1 around 300 K. The optical characterization was performed by modulating the power of a 635 nm laser diode and was carried out at different bias currents and temperatures. Finally, the frequency dependence of the bolometer presented at different temperatures and at optimal current shows that both sensitive and fast uncooled bolometers can be fabricated using suspended LSMO thin films. Keywords: bolometer; thermal conductance; frequency response 1. Introduction A bolometer is a thermal radiation detector whose electrical resistance varies with the temperature rise due to the absorption of the incoming electromagnetic radiation [1].