Lessons Learned from Success and Failure in Participatory Modeling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record-House. January 11

886 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. JANUARY 11, CONFIRMATIONS. the Union Calendar, be referred back to that committee. Is there Executive nomination con.firmed by the Senate Decembe1· 20, 1.900. objection? [After a pause.] The Chair hears none. APPOINTMENT IN THE MARINE-HOSPITAL SERVICE. ACCOUNTS OF MARSHALS AND CLERKS OF DISTRICT COURTS IN THE TERRITORY OF UTAH. Benjamin S. Warren, of Alabama, to be an assis.tant surgeon in the Marine-Hospital Service of the United States. Mr. KING. Mr. Speaker, I ask unanimous consent for the present consideration of the bill (S. 5231) relating to the accounts Executive nominations con.firmed by the Senate Janua1'y 11, 1901. of United States marshals and clerks of the district courts of the UNITED STA.TES ATTORNEY. Territory of Utah. William G. Wheeler, of Wisconsin, to be attorney of the United _The SPEAKER. The gentleman from Utah asks unanimous States for the western district of Wisconsin. consent for the present consideration of the bill S. 5231, which is on the Speaker's table. POSTMASTER, The Clerk read as follows: David B. Rigdon, to be postmaster at Statesboro, Bu11och Be it enacted, etc., That the United States marshals and the clerks of the County, Ga. district courtg of the Territory of Utah prior to its admission to the Union as a State shall be held accountable only for fees earned in United States cases, in accordance with a decision of the Attorney-General dated Decem· · ber 2, 1891, and all unclosed accounts of such officers shall be settled and HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. closed accordingly. -

Kent County Naturalization Name Index, Aalbers, A

Kent County Naturalization Name Index Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Aalbers Aalbers V62 4 Aalbers Aalbert V24 141 Aalddriks Antonie V16 75 Aalderink John K. V16 355 Aaldrick Matthew V16 308 Aardem Arie V16 304 Aardema Klaas V17 27 Aarnouds Pieter V6 8 Aarnoudse Marenus V15 503 Abagis Chas V30 130 Abbas Sain Allez V49 265 Abbelma Joseph B1 F5 Abbelma Joseph V2 564 Abbott Frank V27 92 Abbott John V45 36 Abbott John V68 33 Abdella Salik V46 117 Abdo Ahamad V29 1 Abdoo Mike V41 168 Abeaf Moses V17 391 Abeaf Moses V17 394 Abel Frederick FW B1 F1 Abel Gustav B1 F4 Abel Gustav V2 540 Abel John W. V5 70 Abel Ludwig V8 134 Friday, January 19, 2001 Page 1 of 1325 Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Abella Salih V68 85 Abezi Albert V25 76 Aboabsee Theab V74 40 Aboasee Theab V18 150 Abood N. B1 F5 Abood Nemy V3 90 Abraham John V17 381 Abrahamson Charles Y. B7 200 Abram John B1 F1 Abramson Morris B1 F3 Abraursz Abram Peter V27 159 Abromaitis Louis V27 381 Abromaitis Louis V67 90 Absmaier Carl V77 4 Accardi Guiseppe V50 79 Acheson John V16 616 Achille Minciotti V51 142 Achtenhof Jakob V15 145 Achter Jan V17 200 Achterhof Henri B1 F1 Achterhof Johannes V15 500 Achterhof Matheus B1 F1 Achtjes John B7 107 Ackermann Joseph V15 282 Acton John C. B7 222 Adair David G. V15 335 Adair Joseph V15 335 Adalphson Emil V18 197 Friday, January 19, 2001 Page 2 of 1325 Last name First name Middle name Volume Page Fir Sec Adam Frickartz Heinrich V41 279 Adama Jelle V22 176 Adamawiczus Baltris V37 155 Adamczak Peter V38 245 Adamczyk Wladyslaw V35 291 Adams Edward John V24 70 Adams Frank B1 F2 Adams George W. -

Outlist 2010

Christopher Deal Bridget Hardy Gloria Leung Iris Ouyang Erica Shieh Brad Wergley Hiroshi Sasaki Viktor Kerney Jeremy Allen Elina Khodorkovsky Adam Wyatt Graduate Student, Master’s in Human Junior, Environmental Studies Freshman, Neuroscience Graduate Student, Linguistics Junior, Music Industry Senior, Cinema-Television Production Adjunct Assistant Professor, Masters Assistant Director for Student Leadership, Alumnus, B.A. in French, M.Ed. in PASA, Dedicated to LGBT youth that have taken Behavior (MHB) Program, Rossier School of Education Residential Education Alumnus, BA Fine Arts , 2010 Alumnus, B.A. International Relations and Anna Harley-Trochimczyk Ann Li Sara Parker Adam Siegel Marc Wetrich Tony Altimore Global Business, 2009 2004 Jackie DeLeon Senior, Chemical Engineering Junior, Business/IR Freshman, Business Administration in Graduate Student, Social Work Lisa Schweitzer Johnnathan Korver Alumnus, BS, 2001 Regina Lark Diane Yanez their own lives as a result of bullying, Sophomore, Film Production Alecs Harper Shuai Li Management Cinematic Arts Denice Wharton Associate Professor, School of Policy, Talent Acquisition Specialist, Career and Alumnus, Ph.D., 1999 Alumnus, Bachelors, Biology, 2006 Rebeca Delgado Sophomore, LNPS Graduate Student, Civil Engineering Aimee Sienkiewicz Senior, Political Science and Spanish Planning and Development Protective Services Cindy Ananias Sophomore, Writing for Film/Television Chris Passarelli Senior, Psychology Laura Isabel Serna Michael Kurland Alumnus, Health Promotion and Disease Radford Lathan harassment and campus homophobia. Keanna Harper Kevin Liang Senior, Political Science Gracie Wheelan Assistant Professor, School of Cinematic Academic Adviser, LAS College Prevention, 2009 Alumnus, Bachelor of Arts: Religion, Intl Campus Organization List Joshua DeMilta Sophomore, Business/Cinematic Arts Freshman, Biological Sciences Marie Paulo Erica Silva Senior, Critical Studies Arts, Critical Studies Debbie Ananias Relations, 2010 Sophomore, Broadcast Journalism Montana Harrington Alida Liberman Graduate Student, M.Ed. -

Research Highlights

[CLIENT] Dittrich1611 NT1510146 3 March 2017 Research Highlights GOALS Search for the death record of Barbara Dittrich’s alleged twin, Anežka. Find the birth records of Barbara’s other siblings in the Kladno parish records. Continue to extend the ancestry of Barbara Dittrich in available Czech records. PROGRESS Determined that Barbora Anežka was not a twin. Though unusual for Bohemia, many children in Kladno at that time had middle names. Reexamined the client’s information about Barbora’s siblings, and noted the town Libušín was listed for two of their births. Libušín was part of the Smečno parish, and that it was right outside of Kladno. It now appears that the family moved from Kladno to Libušín between 1892 and 1894. Discovered Barbora’s younger sister Agnes/Anežka’s marriage record in Canada to Antony Kraus. Also discovered her death record, which listed a second husband and her birth in Libušin. According to the client’s information, she had married Antony Kraus and had sons named Tony and Joe. We found her gravestone, and that of two of her children, Joseph and Agnes. Attempted to search the Libušín birth records for Barbora’s siblings but discovered that the relevant parish registers for Smečno are not yet digitized. The relevant book, Smečno 42, was also not available onsite. Sent an email requesting a search of the Libušín birth records after 1900 at the Libušín vital records office. Searched the available Kladno birth records from 1865-1870 for the births of Barbora’s parents. Their births were not found, but several more Dittrich and Veselý siblings for both parents were discovered in the process. -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

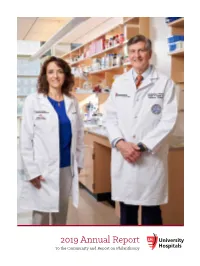

2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy

2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy Cover: Leading UH research on COVID-19, Grace McComsey, MD, Vice President of Research and Associate Chief Scientific Officer, UH Clinical Research Center, Rainbow Babies & Children's Foundation John Kennell Chair of Excellence in Pediatrics, and Division Chief of Infectious Diseases, UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital; and Robert Salata, MD, Chairman, Department of Medicine, STERIS Chair of Excellence in Medicine and and Master Clinician in Infectious Disease, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and Program Director, UH Roe Green Center for Travel Medicine and Global Health, are Advancing the Science of Health and the Art of Compassion. Photo by Roger Mastroianni The 2019 UH Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy includes photographs obtained before Ohio's statewide COVID-19 mask mandate. INTRODUCTION REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY 5 Letter to Friends 38 Letter to our Supporters 6 UH Statistics 39 A Gift for the Children 8 UH Recognition 40 Honoring the Philanthropic Spirit 41 Samuel Mather Society UH VISION IN ACTION 42 Benefactor Society 10 Building the Future of Health Care 43 Revolutionizing Men's Health 12 Defining the Future of Heart and Vascular Care 44 Improving Global Health 14 A Healing Environment for Children with Cancer 45 A New Game Plan for Sports Medicine 16 UH Community Highlights 48 2019 Endowed Positions 18 Expanding the Impact of Integrative Health 54 Annual Society 19 Beating Cancer with UH Seidman 62 Paying It Forward 20 UH Nurses: Advancing and Evolving Patient Care 63 Diamond Legacy Society 22 Taking Care of the Browns. -

Program for the 2021 Convocation Celebrations PROGRAM

Program for the 2021 Convocation Celebrations PROGRAM Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Convocation Though this is a remote celebration, the accomplish- Ceremony has been converted into three Convocation ments of the individuals named in this Convocation celebrations. The 2021 Fellowship Convocation cele- Program are worthy of highest esteem and honor. The bration recognizes the achievements of recipients of American College of Physicians celebrates their achieve- Fellowship since 2017 who have not yet participated ments and contributions to ACP and internal medicine. in a Convocation Ceremony. The 2021 Mastership and Honorary Fellowship Convocation celebration recognizes recipients of Mastership in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 awards cycles as well as recipients of __________________________________________________ Honorary Fellowship and global dignitaries invited as Special Representatives. The 2021 National and Chapter * The American College of Physicians thanks the Awards Convocation celebration recognizes recipients endowers and sponsors of several awards: the James of ACP national awards in the 2019-20 and 2020-21 Bruce family, the Ralph O. Claypoole Jr. family, the awards cycles as well as recipients of ACP Chapter Feinstein family, and the Samuel Eichold family with awards in 2019 and 2020. the Alabama Chapter. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACP Leadership .................................................. 1 About Convocation, the President’s Badge, the Special Representatives ......................................3 Caduceus, and the Mace ................................90 -

"'L · Rf.\I Lf( ~ L

'Wi{{/(jruntfy (jenea{ogica{ Society honors a pioneer, I 'Wi{{iam 'I. !/{e{son, who lived in Will County in 1 848. William T. Nelson was the second of nine known children born to John and Elizabeth (Gray) Nelson. His father, born about the year 1786, was of Scots-Irish descent and was raised in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, 'later living in Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana before moving to Twelve Mile Grove, Will Co., Illinois in 1848. He had served in the War of 1 81 2 and also represented his county in the Indiana legislature while residing there. Born on the 9th day of January 181 8 in Ohio, William came to Will County with his parents, along with four of his brothers and sisters - Esther Jane, Samuel G., ·Mary and Daniel Mc. He was married in the early 1850's to Celia Annette Derke/Durkee, born 5 February 1825 in Indiana. Five children were born to the couple - Mary Freelove, Sarah Annette, Kate G., William and Thomas M. Mr. Nelson was a nurseryman, owner of the Wilmington Nursery. He is thought to have produced the "Nelson apple," which was highly regarded prior to the advent of refrigeration. Along with his brothers Samuel and Daniel, he was active in civic affairs. He served as secretary of the Will Co. Fair and was a charter member of Wilmington Masonic Lodge #208. The death of William T. Nelson occurred on the 11th of December 1903 in Chicago, where he had made his home with his daughter Sarah, Mrs. Daniel "Mac" White, after the death of his wife in 1 888. -

2018 BMES MOBILE THURSDAY Annual Meeting Platform Sessions Th-1 APP (Thursday 8:00-9:30Am)

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM 2018 BMES MOBILE THURSDAY Annual Meeting Platform Sessions Th-1 APP (Thursday 8:00-9:30am) ....................................... 4–13 Go to the Apple or Android Store and search for: Platform Sessions Th-2 BMES (Thursday 1:30-3:00pm) ....................................14–22 Download the Free App > Select BMES2018 Platform Sessions Th-3 (Thursday 3:45-5:15pm) ....................................23–31 Poster Sessions–Thursday ..............................32–91 Browse the program by date or session type FRIDAY Platform Sessions Fri-1 keywords Search (Friday 8:00-9:30am) ....................................... 93–101 Search Author list Platform Sessions Fri-2 Add presentations to (Friday 1:15-2:45pm) .................................. 102–110 a custom itinerary Platform Sessions Fri-3 Click a link to show (Friday 3:30-5:00pm) .................................... where a presentation 111–119 is on the map of the convention center Poster Sessions–Friday .............................. 120–179 SATURDAY Platform Sessions Sat-1 (Saturday 8:00am-9:30am) .........................180–189 Platform Sessions Sat-2 Don't forget to turn your BMES (Saturday 1:30-3:00pm) ............................... 190–198 BASH ticket in for a wristband at Platform Sessions Sat-3 (Saturday 3:15-4:45pm) ...............................199–205 the information or registration Poster Sessions–Saturday ....................... 206–249 booths before Friday afternoon Omni Hotel Floorplan .......................................... -

(USCIS) FOIA Log June 2016

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) FOIA Log June 2016 Control Number Requester Name Trk Scanned Created Subject BLR2016000038 Alvarado Perez, Crispin 2 06/01/2016 06/07/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070813 Pacheco, Lauro 2 05/24/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070829 Garcia Nieves, Leticia 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070835 Velez, Edgar 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070908 Cuevas Granados, Miguel 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070917 Guerra, Andres 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070941 MacMurray, Kevin 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070943 Sofer, Ted 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070950 Oneil Baker, Erin 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070964 Fleisig, Vina 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070965 Seyfried, Brian 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070969 MacMurray, Kevin 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070972 Fleisig, Vina 1 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070977 Siderman, Sergio 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070983 De Los Santos, Omar 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016070988 Hennessee, Shelley 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016071001 Ibarra Mata, Sandra 2 05/25/2016 06/01/2016 withheld pursuant to (b)(6) NRC2016071027 -

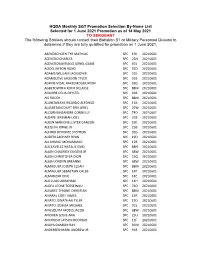

HQDA Monthly SGT Promotion Selection By-Name List Selected For

HQDA Monthly SGT Promotion Selection By-Name List Selected for 1 June 2021 Promotion as of 14 May 2021 TO SERGEANT The following Soldiers should contact their Battalion S1 or Military Personnel Division to determine if they are fully qualified for promotion on 1 June 2021. ABENDSCHOEN TYR MATHIAS SPC 19K 20210601 ACEVEDO CHARLES SPC 25N 20210601 ACEVEDOSANTIAGO ADNEL GABIE SPC 91S 20210601 ACIDO JAYSON AGNO SPC 91D 20210601 ADAMS WILLIAM JACKSON III SPC 31K 20210601 ADAMSLOVE JACKSON TYLER SPC 91B 20210601 ADKINS VIDAL RAKEEMOLAJUWON SPC 92G 20210601 AGBETOWOFA KOFFI DELASSE SPC 88M 20210601 AGUIRRE CELIA CRYSTEL SPC 91B 20210601 AIS ROODY SPC 88M 20210601 ALANIZANAYA RICARDO ALFONSO SPC 11B 20210601 ALASBETANCOURT ERIK ARIEL SPC 92W 20210601 ALCORN KHEANDRE CONNELLY SPC 74D 20210601 ALDAPE JEREMIAH JOEL SPC 31B 20210601 ALDEN MARIONELLISTER GANZON SPC 19K 20210601 ALEQUIN JORGE JR SPC 25B 20210601 ALFORD DEVONTE STEPHON SPC 92G 20210601 ALGIERI ZACHARY RYAN SPC 19D 20210601 ALI AHMAD MOHAMMAD SPC 12B 20210601 ALICEAVELEZ NATALIE ENID SPC 88N 20210601 ALLEN CHADRICK EUGENE JR SPC 68W 20210601 ALLEN CHRISTOFER DION SPC 25Q 20210601 ALLEN JORDYN BREANNE SPC 68W 20210601 ALMAGUER JOSEPH ELIJAH SPC 88M 20210601 ALMAGUER SEBASTIAN CALEB SPC 14P 20210601 ALMANZAR ONIL SPC 14E 20210601 ALO JULIO ABRAHAM SPC 14H 20210601 ALOFA LEONE TOESEINUU SPC 74D 20210601 ALVAREZ TYRONE CHRISTIAN SPC 88M 20210601 AMARAL CORY JAMES SPC 15R 20210601 AMATO JONATHAN TYLER SPC 19D 20210601 AMATO JOSHUA MICHAEL SPC 91S 20210601 AMESQUITA MOSES JACOB SPC 68W 20210601 -

Afics BULLETIN

afics BULLETIN • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • •• • • ••• • • ••• • • • ••• • • • •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••×•• • • • •••••••••••• ••••• ••• • • ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• neW YorK ASSOCIATION OF FORMER INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS Vol. 47 ♦ No. 1 ♦ Spring / Summer 2015 1945 — 2015 AFICS/NY congratulates the United Nations on 70 years of working for peace and security, development and human rights. (See page 36 for UN 70 events in Sept. and Oct.) •••••••• • • •••••••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • •••• •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • • • • • • •• •• • •• • •• • ••••••••••••••••••••• “The mission of AFICS/NY is to support and promote the purposes, principles and programmes of the UN System; to advise and assist former international civil servants and those about to separate from service; to represent the interests of its members within the System; to foster social and personal relationships among members, to promote their well-being and to encourage mutual support of individual members." CONTENTS ASSOCIATION OF FORMER INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS/New YorK 3 NOTES FROM THE PRESIDENT Honorary Members 5 ANNUAL ASSEMBLY & RECEPTION Martti Ahtisaari Aung San Suu Kyi 5 Statement on behalf of President of 69th Session Kofi A. Annan Boutros Boutros-Ghali of the General Assembly Ban Ki-moon Javier Pérez de Cuéllar 6 Statement of Under-Secretary-General for Human Resources Management 7 Statement of Assistant Secretary-General GOVERNING BOARD 8 Report from UN Health and Life Insurance Section HONORARY MEMBERS 9 Address by the President of AFICS/NY 13 Election of AFICS/NY Governing Board Members Andrés Castellanos del Corral George F. Saddler 13 Statement of CEO of UNJSPF O. Richard Nottidge Jane Weidlund 16 Statement by the Representative of the Edward Omotoso Secretary-General for Investments (RSG) Officers 18 FAFICS IN ACTION 18 Highlights of Messages to Pension Board President Secretary 19 Retire in Malta Linda Saputelli Anthony J.