Integrating Biodiversity and Drinking Water Protection Goals Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations Potential health effects MCL or TT1 Common sources of contaminant in Public Health Contaminant from long-term3 exposure (mg/L)2 drinking water Goal (mg/L)2 above the MCL Nervous system or blood Added to water during sewage/ Acrylamide TT4 problems; increased risk of cancer wastewater treatment zero Eye, liver, kidney, or spleen Runoff from herbicide used on row Alachlor 0.002 problems; anemia; increased risk crops zero of cancer Erosion of natural deposits of certain 15 picocuries Alpha/photon minerals that are radioactive and per Liter Increased risk of cancer emitters may emit a form of radiation known zero (pCi/L) as alpha radiation Discharge from petroleum refineries; Increase in blood cholesterol; Antimony 0.006 fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; decrease in blood sugar 0.006 solder Skin damage or problems with Erosion of natural deposits; runoff Arsenic 0.010 circulatory systems, and may have from orchards; runoff from glass & 0 increased risk of getting cancer electronics production wastes Asbestos 7 million Increased risk of developing Decay of asbestos cement in water (fibers >10 fibers per Liter benign intestinal polyps mains; erosion of natural deposits 7 MFL micrometers) (MFL) Cardiovascular system or Runoff from herbicide used on row Atrazine 0.003 reproductive problems crops 0.003 Discharge of drilling wastes; discharge Barium 2 Increase in blood pressure from metal refineries; erosion 2 of natural deposits Anemia; decrease in blood Discharge from factories; leaching Benzene -

Module 1 Basics of Water Supply System

Module 1 BASICS OF WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM Training Module for Local Water and Sanitation Management Maharashtra Jeevan Pradhikaran (MJP) CEPT University 2012 Basics of Water Supply System- Training Module for Local Water and Sanitation Management CONTENT Introduction 3 Module A Components of Water Supply System 4 A1 Typical village/town Water Supply System 5 A2 Sources of Water 7 A3 Water Treatment 8 A4 Water Supply Mechanism 8 A5 Storage Facilities 8 A6 Water Distribution 9 A7 Types of Water Supply 10 Worksheet Section A 11 Module B Basics on Planning and Estimating Components of Water Supply 12 B1 Basic Planning Principles of Water Supply System 13 B2 Calculate Daily Domestic Need of Water 14 B3 Assess Domestic Waste Availability 14 B4 Assess Domestic Water Gap 17 B5 Estimate Components of Water Supply System 17 B6 Basics on Calculating Roof Top Rain Water Harvesting 18 Module C Basics on Water Pumping and Distribution 19 C1 Basics on Water Pumping 20 C2 Pipeline Distribution Networks 23 C3 Type of Pipe Materials 25 C4 Type of Valves for Water Flow Control 28 C5 Type of Pipe Fittings 30 C6 Type of Pipe Cutting and Assembling Tools 32 C7 Types of Line and Levelling Instruments for Laying Pipelines 34 C8 Basics About Laying of Distribution Pipelines 35 C9 Installation of Water Meters 42 Worksheet Section C 44 Module D Basics on Material Quality Check, Work Measurement and 45 Specifications in Water Supply System D1 Checklist for Quality Check of Basic Construction Materials 46 D2 Basics on Material and Item Specification and Mode of 48 Measurements Worksheet Section D 52 Module E Water Treatment and Quality Control 53 E1 Water Quality and Testing 54 E2 Water Treatment System 57 Worksheet Section E 62 References 63 1 Basics of Water Supply System- Training Module for Local Water and Sanitation Management ABBREVIATIONS CPHEEO Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation cu. -

Design and Production of Drinking-Water Supply Network

OUR EXPERT ASSESSMENT DESIGN AND PRODUCTION OF A DRINKING-WATER SUPPLY NETWORK Especially committed to fighting water related diseases and unsanitary conditions, SOLIDARITES INTERNATIONAL (SI) has been involved in the field of access to drinking water and sanitation for almost 35 years. The annual number of deaths caused by these diseases has risen to 2.6 million, making it one of the world’s leading causes of death; amongst these victims, 1.8 million children, aged less than 15, still succumb... Today, when more than a billion people are still deprived of access to drinking water and permanently exposed to water-related diseases, the right to drinking water remains a vital concern in developing countries. In this regard, drinking-water supply networks represent quite a relevant technical solution for supplying water to refugees, as well as to dense populations and areas with high population growth. In order to further advance technical and socioeconomic diagnoses, SOLIDARITES INTERNATIONAL has led many projects, sometimes lasting years, in partnership with institutions and legitimate operators from the water sector. Hydraulic components and civil engineering relating to rehabilitation, growth and the construction of infrastructure are inseparable from the accompanying social measures, which involve placing sustainability, with the concerted management of water services and the participation of the community, at the heart of the process. Repairing, renovating or building a drinking-water network is a relevant ANALYSING AND ADAPTING technical response when the humanitarian emergency situation requires the re-establishment of the water supply and following the very first emergency TO COMPLEX measures (tanks, mobile treatment units). -

Effectiveness of Virginia's Water Resource Planning and Management

Commonwealth of Virginia House Document 8 (2017) October 2016 Report to the Governor and the General Assembly of Virginia Effectiveness of Virginia’s Water Resource Planning and Management 2016 JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT AND REVIEW COMMISSION Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission Chair Delegate Robert D. Orrock, Sr. Vice-Chair Senator Thomas K. Norment, Jr. Delegate David B. Albo Delegate M. Kirkland Cox Senator Emmett W. Hanger, Jr. Senator Janet D. Howell Delegate S. Chris Jones Delegate R. Steven Landes Delegate James P. Massie III Senator Ryan T. McDougle Delegate John M. O’Bannon III Delegate Kenneth R. Plum Senator Frank M. Ruff, Jr. Delegate Lionell Spruill, Sr. Martha S. Mavredes, Auditor of Public Accounts Director Hal E. Greer JLARC staff for this report Justin Brown, Senior Associate Director Jamie Bitz, Project Leader Susan Bond Joe McMahon Christine Wolfe Information graphics: Nathan Skreslet JLARC Report 486 ©2016 Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission http://jlarc.virginia.gov February 8, 2017 The Honorable Robert D. Orrock Sr., Chair Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission General Assembly Building Richmond, Virginia 23219 Dear Delegate Orrock: In 2015, the General Assembly directed the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) to study water resource planning and management in Virginia (HJR 623 and SJR 272). As part of this study, the report, Effectiveness of Virginia’s Water Resource Planning and Management, was briefed to the Commission and authorized for printing on October 11, 2016. On behalf of Commission staff, I would like to express appreciation for the cooperation and assistance of the staff of the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality and the Virginia Water Resource Research Center at Virginia Tech. -

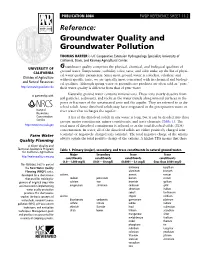

Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution

PUBLICATION 8084 FWQP REFERENCE SHEET 11.2 Reference: Groundwater Quality and Groundwater Pollution THOMAS HARTER is UC Cooperative Extension Hydrogeology Specialist, University of California, Davis, and Kearney Agricultural Center. roundwater quality comprises the physical, chemical, and biological qualities of UNIVERSITY OF G ground water. Temperature, turbidity, color, taste, and odor make up the list of physi- CALIFORNIA cal water quality parameters. Since most ground water is colorless, odorless, and Division of Agriculture without specific taste, we are typically most concerned with its chemical and biologi- and Natural Resources cal qualities. Although spring water or groundwater products are often sold as “pure,” http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu their water quality is different from that of pure water. In partnership with Naturally, ground water contains mineral ions. These ions slowly dissolve from soil particles, sediments, and rocks as the water travels along mineral surfaces in the pores or fractures of the unsaturated zone and the aquifer. They are referred to as dis- solved solids. Some dissolved solids may have originated in the precipitation water or river water that recharges the aquifer. A list of the dissolved solids in any water is long, but it can be divided into three groups: major constituents, minor constituents, and trace elements (Table 1). The http://www.nrcs.usda.gov total mass of dissolved constituents is referred to as the total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration. In water, all of the dissolved solids are either positively charged ions Farm Water (cations) or negatively charged ions (anions). The total negative charge of the anions always equals the total positive charge of the cations. -

Lesson 3 - Water and Sewage Treatment

Unit: Chemistry D – Water Treatment LESSON 3 - WATER AND SEWAGE TREATMENT Overview: Through notes, discussion and research, students learn about how water and sewage are treated in rural and urban areas. Through discussion and online research, the sources, safety, treatment and cost of bottled water are considered. Using this information, students then share their views on bottled water. Suggested Timeline: 2 hours Materials: Watery Facts (Teacher Support Material) Water and Sewage Treatment (Teacher Support Material) A Closer Look at Water Treatment – Teacher Key (Teacher Support Material) All Tapped Out? – A Look At Bottled Water (Teacher Support Material) materials for bottled water demonstration: - plastic cups - 3 or more brands of bottled water - a sample of municipal tap water - a sample of local well water Water and Sewage Treatment (Student Handout – Individual) Water and Sewage Treatment (Student Handout – Group) A Closer Look at Water Treatment (Student Handout) All Tapped Out? – A Look At Bottled Water (Student Handout) student access to computers with the Internet and speakers Method: INDIVIDUAL FORMAT: 1. Have students read and complete the questions on ‘Water and Sewage Treatment’ (Student Handout – Individual). 2. Using computers with Internet access and speakers, allow students to research answers to questions on ‘A Closer Look at Water Treatment’ (Student Handout) 3. If possible, use one or more of the ideas on ‘All Tapped Out? – A Look At Bottled Water’ (Teacher Support Material) to spark students’ interest in the issues associated with bottled water. 4. Using computers with Internet access, have students complete the research on bottled water on ‘All Tapped Out? – A Look At Bottled Water’ (Student Handout). -

A Public Health Legal Guide to Safe Drinking Water

A Public Health Legal Guide to Safe Drinking Water Prepared by Alisha Duggal, Shannon Frede, and Taylor Kasky, student attorneys in the Public Health Law Clinic at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law, under the supervision of Professors Kathleen Hoke and William Piermattei. Generous funding provided by the Partnership for Public Health Law, comprised of the American Public Health Association, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association of County & City Health Officials, and the National Association of Local Boards of Health August 2015 THE PROBLEM: DRINKING WATER CONTAMINATION Clean drinking water is essential to public health. Contaminated water is a grave health risk and, despite great progress over the past 40 years, continues to threaten U.S. communities’ health and quality of life. Our water resources still lack basic protections, making them vulnerable to pollution from fracking, farm runoff, industrial discharges and neglected water infrastructure. In the U.S., treatment and distribution of safe drinking water has all but eliminated diseases such as cholera, typhoid fever, dysentery and hepatitis A that continue to plague many parts of the world. However, despite these successes, an estimated 19.5 million Americans fall ill each year from drinking water contaminated with parasites, bacteria or viruses. In recent years, 40 percent of the nation’s community water systems violated the Safe Drinking Water Act at least once.1 Those violations ranged from failing to maintain proper paperwork to allowing carcinogens into tap water. Approximately 23 million people received drinking water from municipal systems that violated at least one health-based standard.2 In some cases, these violations can cause sickness quickly; in others, pollutants such as inorganic toxins and heavy metals can accumulate in the body for years or decades before contributing to serious health problems. -

Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering

water Article Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering Slobodan P. Simonovic Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 5B9, Canada; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-661-4075 Received: 29 March 2020; Accepted: 20 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Abstract: Global change, that results from population growth, global warming and land use change (especially rapid urbanization), is directly affecting the complexity of water resources management problems and the uncertainty to which they are exposed. Both, the complexity and the uncertainty, are the result of dynamic interactions between multiple system elements within three major systems: (i) the physical environment; (ii) the social environment; and (iii) the constructed infrastructure environment including pipes, roads, bridges, buildings, and other components. Recent trends in dealing with complex water resources systems include consideration of the whole region being affected, explicit incorporation of all costs and benefits, development of a large number of alternative solutions, and the active (early) involvement of all stakeholders in the decision-making. Systems approaches based on simulation, optimization, and multi-objective analyses, in deterministic, stochastic and fuzzy forms, have demonstrated in the last half of last century, a great success in supporting effective water resources management. This paper explores the future opportunities that will utilize advancements in systems theory that might transform management of water resources on a broader scale. The paper presents performance-based water resources engineering as a methodological framework to extend the role of the systems approach in improved sustainable water resources management under changing conditions (with special consideration given to rapid climate destabilization). -

WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality : Selected Pollutants

WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: WHO GUIDELINES FOR INDOOR AIR QUALITY: This book presents WHO guidelines for the protection of pub- lic health from risks due to a number of chemicals commonly present in indoor air. The substances considered in this review, i.e. benzene, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, naphthalene, nitrogen dioxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (especially benzo[a]pyrene), radon, trichloroethylene and tetrachloroethyl- ene, have indoor sources, are known in respect of their hazard- ousness to health and are often found indoors in concentrations of health concern. The guidelines are targeted at public health professionals involved in preventing health risks of environmen- SELECTED CHEMICALS SELECTED tal exposures, as well as specialists and authorities involved in the design and use of buildings, indoor materials and products. POLLUTANTS They provide a scientific basis for legally enforceable standards. World Health Organization Regional Offi ce for Europe Scherfi gsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Tel.: +45 39 17 17 17. Fax: +45 39 17 18 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.euro.who.int WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: selected pollutants The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health, Bonn Office, WHO Regional Office for Europe coordinated the development of these WHO guidelines. Keywords AIR POLLUTION, INDOOR - prevention and control AIR POLLUTANTS - adverse effects ORGANIC CHEMICALS ENVIRONMENTAL EXPOSURE - adverse effects GUIDELINES ISBN 978 92 890 0213 4 Address requests for publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for per- mission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). -

Concerns About Surface Water As a Drinking Water Source

Concerns About Surface Water NEW YORK STATE as a Drinking Water Source DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH The New York State Department of Health wants to remind people that there are risks from using water from any surface water source as drinking water, unless that water is properly filtered and disinfected. Water from rivers, lakes, ponds and streams can contain bacteria, parasites, viruses and possibly other contaminants. To make surface water fit to drink, treatment is required. Remember, we use our drinking water in many different ways. We use it as a beverage, but also make ice cubes, mix baby formula, wash fruits and vegetables, and brush our teeth. If the water is contaminated, this may put you at risk. Depending on the kind of contamination, it may also be a concern to wash dishes, wash hands, shower or bathe. Public water systems are required to treat, disinfect and monitor water quality for their customers. A public water treatment system is well designed and employs trained technicians to test and maintain water quality. If you are not on a public water system and use surface water as your water supply source, please contact your local health department* for advice. They can talk to you about developing another source of drinking water in your area. If there are no other choices, then they can discuss the treatment options for your surface water source. In the meantime, avoid the use of surface water for your drinking water needs. You should use bottled water or disinfect small batches of water by bringing it to a rolling boil for one – two minutes. -

Elements for an Outline of a Review of Water Supply Reliability Estimation Related to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board

DRAFT Elements for an Outline of a Review of Water Supply Reliability Estimation related to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board 7/6/2019 Summary findings and recommendations Section outlines 1) Introduction a) Purpose: Uses of water supply reliability estimates– questions asked b) Scope: Urban, agricultural, environmental, regulatory perspectives, regional systems c) Incomplete inventory of reliability estimation efforts d) Changing challenges and questions (Portfolios in reliability, Water quality, Environmental water reliability, Climate change, Conflicts in water management) e) Structure of report 2) Metrics of water supply reliability 3) Scientific underpinning of trends in water supply reliability a) Portfolios in reliability b) Water quality c) Environmental water reliability d) Climate change e) Multiple objectives and conflicts in water management 4) Developing and communicating insights for managers and policymakers a) Long-term education and insights for policy-makers b) Transparency c) Potential for decision analysis 5) Quality control in reliability estimation a) Peer review b) Common standards or expectations? c) Common efforts (1) Land use, inflows, groundwater modeling, portfolio characterization, etc. (2) Common water accounting 6) Priorities for future studies a) Ecological and environmental water reliability b) Incorporating climate change and sea level rise c) FIRO d) Fragility analysis 7) Conclusions and Recommendations Delta ISB Meeting Materials (7/11/19) 1 DRAFT References Appendices -

Short-Term Water Management Decisions

Short-Term Water Management Decisions User Needs for Improved Climate, Weather, and Hydrologic Information Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) January 2013 Technical Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Short-Term Water Management Decisions: 5b. GRANT NUMBER User Needs for Improved Climate, Weather, and Hydrologic Information 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER David Raff, Levi Brekke, Kevin Werner, Andy Wood, and Kathleen White 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Bureau of Reclamation CWTS 2013-1 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 9. SPONSORING / MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10.