The Robot in Healthcare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Who and the Zarbi Free

FREE DOCTOR WHO AND THE ZARBI PDF Bill Strutton | 176 pages | 11 Jul 2017 | Ebury Publishing | 9781785940545 | English | London, United Kingdom How to Find a Doctor That one time in Portugal,where the guy who illustrated the cover for Doctor Who and the Zarbi decided to create the Rocket Men, instead of drawing actual Menoptras. Zarbi from planet Vortis, Doctor Who. First published by Frederick Muller Ltd. This edition, published by White Lion infeatures Tom Baker, then the Doctor, on the cover - despite Doctor Who and the Zarbi the original illustrations of William Hartnell within. Radio Times 27 March-2 April Keep reading. On the back cover, the First Doctor was originally drawn to look younger, only to be covered with a more accurate illustration. This beautiful piece of artwork from the original Doctor Who Annual Cover Published by World Distributors. This piece used to hang on the wall of the company Directors office but an order was given, when the company ceased into skip all the artwork archive. This original cover was rescued by one of the World Doctor Who and the Zarbi employees and kept safe for the last 17 years. Very proud to be the owner of this iconic original piece. According to artist Stanley Freeman who worked at World Distributors, it was him who created the cover art. In earlyhe created the cover for the first Doctor Who Annual, until now generally credited to Walter Howarth. A photo of William Hartnell to follow in the post. I must admit my memory is a bit woolly on the sub-cast on the cover. -

Edscratch Teachers Guide

Teaching guide and answer key The EdScratch Lesson Plans Set by Kat Kennewell and Jin Peng is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Document number: 3.2.4.3.1 Rev 1.1 About this guide .................................................................................................................... 3 What’s in this guide ........................................................................................................... 3 Creative Commons licence ............................................................................................... 3 How to use this guide ............................................................................................................ 4 Understanding the activity types ........................................................................................ 4 Reading the activity overview ............................................................................................ 5 Using the answer key ........................................................................................................ 6 Supplies you will need ....................................................................................................... 7 Frequently asked questions .............................................................................................. 8 Before you start ................................................................................................................... 12 Get Edison ready ........................................................................................................... -

Digital Booklet

ORIGINAL TELEVISION SCORE ADDITIONAL CUES FOR 4-PART VERSION 01 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors) 0.36 34 End of Episode 1 (Sarah Falls) 0.11 02 New Console 0.24 35 End of Episode 2 (Cybermen III variation) 0.13 03 The Eye of Orion 0.57 36 End of Episode 3 (Nothing to Fear) 0.09 04 Cosmic Angst 1.18 05 Melting Icebergs 0.40 37 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue (Premix) 1.22 06 Great Balls of Fire 1.02 07 My Other Selves 0.38 08 No Coordinates 0.26 09 Bus Stop 0.23 10 No Where, No Time 0.31 11 Dalek Alley and The Death Zone 3.00 12 Hand in the Wall 0.21 13 Who Are You? 1.04 14 The Dark Tower / My Best Enemy 1.24 15 The Game of Rassilon 0.18 16 Cybermen I 0.22 17 Below 0.29 18 Cybermen II 0.58 19 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen III 0.34 20 Raston Robot 0.24 21 Not the Mind Probe 0.10 22 Where There’s a Wind, There’s a Way 0.43 23 Cybermen vs Raston Robot 2.02 24 Above and Between 1.41 25 As Easy as Pi 0.23 26 Phantoms 1.41 27 The Tomb of Rassilon 0.24 28 Killing You Once Was Never Enough 0.39 29 Oh, Borusa 1.21 30 Mindlock 1.12 31 Immortality 1.18 32 Doctor Who Closing Theme - The Five Doctors Edit 1.19 33 Death Zone Atmosphere 3.51 SPECIAL EDITION SCORE 56 The Game of Rassilon (Special Edition) 0.17 57 Cybermen I (Special Edition) 0.22 38 Doctor Who - Opening Theme (The Five Doctors Special Edition) 0.35 58 Below (Special Edition) 0.43 39 The Five Doctors Special Edition: Prologue 1.17 59 Cybermen II (Special Edition) 1.12 40 The Eye of Orion / Cosmic Angst (Special Edition) 2.22 60 The Castellan Accused / Cybermen -

You Might Be a Robot

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CRN\105-2\CRN203.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAY-20 13:27 YOU MIGHT BE A ROBOT Bryan Casey† & Mark A. Lemley‡ As robots and artificial intelligence (AI) increase their influ- ence over society, policymakers are increasingly regulating them. But to regulate these technologies, we first need to know what they are. And here we come to a problem. No one has been able to offer a decent definition of robots and AI—not even experts. What’s more, technological advances make it harder and harder each day to tell people from robots and robots from “dumb” machines. We have already seen disas- trous legal definitions written with one target in mind inadver- tently affecting others. In fact, if you are reading this you are (probably) not a robot, but certain laws might already treat you as one. Definitional challenges like these aren’t exclusive to robots and AI. But today, all signs indicate we are approaching an inflection point. Whether it is citywide bans of “robot sex brothels” or nationwide efforts to crack down on “ticket scalp- ing bots,” we are witnessing an explosion of interest in regu- lating robots, human enhancement technologies, and all things in between. And that, in turn, means that typological quandaries once confined to philosophy seminars can no longer be dismissed as academic. Want, for example, to crack down on foreign “influence campaigns” by regulating social media bots? Be careful not to define “bot” too broadly (like the California legislature recently did), or the supercomputer nes- tled in your pocket might just make you one. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC. -

Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas Mcmurtry, LG

Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas McMurtry, LG Title Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas Authors McMurtry, LG Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/44368/ Published Date 2013 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Leslie McMurtry Swansea University Doctor Who, Steampunk, and the Victorian Christmas “It’s everywhere these days, isn’t it? Anime, Doctor Who, novel after novel involving clockwork and airships.” --Catherynne M. Valente1 Introduction It seems nearly every article or essay on Neo-Victorianism must, by tradition, begin with a defence of the discipline and an explanation of what is currently encompassed by the term— or, more likely, what is not. Since at least 2008 and the launch of the interdisciplinary journal Neo-Victorian Studies, scholars have been grappling with a catch-all definition for the term. Though it is appropriate that Mark Llewellyn should note in his 2008 “What Is Neo-Victorian Studies?” that “in bookstores and TV guides all around us what we see is the ‘nostalgic tug’ that the (quasi-) Victorian exerts on the mainstream,” Imelda Whelehan is right to suggest that the novel is the supreme and legitimizing source2. -

Terror of the Autons

THE ROBOTS OF DEATH By Chris Boucher Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 200601 Revision 10 By the usual suspects Transcription by Steve Hill Dun de dun Tunnel RCW: Presented in TUNNEL-VISION! Face Diamond logo The Robots of Death SAW: Well, I guess we already know who the killers are. By Chris Boucher MO: (French accent) That would be Chris Boo-shay. A planet, bathed in green and purple light. RCW: Oh look! Rocks! SWH: By the light of the purple and green suns… Rocks are falling. SAW: Ricola! SWH: The forecast is for continued dry conditions here at The wind is fierce. Mr. Rogers’ former neighborhood. It’s day eighteen million of the drought and still no end in sight. There's a huge ship riding the rocks. MO: Is that K9? Drills mounted on the side plow through the rocks. SWH: Poof! The bridge is seen, with much activity, in long shot. RCW: Insert chromakey here. Then we are aboard the ship, where many art deco robots walk around doing things. ALL: Domo Arigato, Mr Roboto! Domo, domo. SAW: Hey, we figured, why sit on that one? V32 Turbulence center, vector seven. V32 walks up to a console and stands for a moment. V32 Scan commencing now. MO: Look UP… CHUB There was a voc therapist in Kaldor City. Specially programmed, equipped with vibro digits, subcutaneous RCW: They have a lot of movies. stimulators, the lot. You know what happened, Borg? Its first client wanted treatment for a stiff elbow. The voc therapist felt carefully all round the joint, and then suddenly just… twisted his arm off at the shoulder – MO: Like this! shoomf! He he he. -

Unit 6: Robotics EXPLORING COMPUTER SCIENCE

Version 7.0 Unit 6: Robotics EXPLORING COMPUTER SCIENCE ©University of Oregon, 2016 Exploring Computer Science—Unit 6: Robotics 260 ©University of Oregon, 2016. Please do not copy or distribute this curriculum without written permission from ECS. Version 7.0 Introduction Robotics provides a physical application of the programming and problem solving skills acquired in the previous units. Robots are shared by several students, which will emphasize the collaborative nature of computing. In order to design, build and improve their robots, students will need to apply effective team practices and understand the different roles that are important for success. Discussing the features of robots provides an opportunity to emphasize how computing has far-reaching effects on society and has led to significant innovation. Students can discuss such topics as: • The effects innovations in robotics have had on people. • The significance of processes that have been automated because of robots. • How innovations in robotics have spurred additional innovations. The unit consists of three main sections: • The features of robots (Days 1-3) • Familiarization with the robot and the software (Days 4-13) • Robotics projects (Days 14-33) The Edison Robot software utilized for this unit uses drag and drop programming, which will provide a natural transition from Scratch. Note that these three main sections can be applied to different types of robots, such as Finch robots. Teachers can use the same lesson plans, but substitute the appropriate robot and software. Throughout the unit the similarities and differences between Scratch and the programming needed to move the robot can be highlighted. In addition to robotics, there are other applications that share the feature of combining programming software and a device of some type. -

Week 4 Term 5 Zebra Class Home Learning Guide

Zebra Class Home Learning Term 5 Week 4 Welcome to Week 4 of our Superheroes topic! Thank you to everyone who has sent work or comments to the Zebra Class email address. We are so grateful for your continued support. We have really enjoyed reading the writing about real life superheroes and seeing videos and photos of the children reading and doing maths. It has also been very helpful to know that the children are benefitting from the videos that we have made. We have made more videos for you for this week, with the links included in this guide. We have also been looking at how the children have been getting on with Reading Eggs and Mathletics. We now have over 25000 points on Mathletics and even more lessons have been completed on Reading Eggs, which is wonderful! If you are able to photograph or video your child’s learning for this week, we would love to see what he or she has done. This could be every few days, or at the end of the week, whatever suits the needs of your family. This also allows us to provide you and your child with feedback and advice. Please also get in touch with any questions regarding the activities set. Our email address is [email protected] Mrs Rich and Mrs Midgley Introduction to the Police listening and talking activity (30 minutes) Today we are going to start by thinking about some more real-life superheroes, the Police. They help to keep us safe and make sure that everyone is following the rules. -

From Cybermen to the TARDIS: How the Robots of Doctor Who Portray a Nuanced View of Humans and Technology

From Cybermen to the TARDIS: How the Robots of Doctor Who Portray a Nuanced View of Humans and Technology GWENDELYN S. NISBETT AND NEWLY PAUL Critics and fans have praised the 2000s reboot of the science fiction classic Doctor Who for its increasing use of social commentary and politically relevant narratives. The show features the adventures of the Doctor and his companions, who have historically been humans, other aliens, and occasionally robots. They travel through time and space on a spaceship called the TARDIS (which is shaped like a 1960s British police box). The show is meant for younger audiences, but the episodes involve political and social commentary on a range of issues, such as racism, sexism, war, degradation of the environment, and colonialism. The Doctor is an alien from Gallifrey and can (and does) regenerate into new versions of the Doctor. Scholars have commented extensively about the show in the context of gender and race, political messaging, transmedia storytelling, and fandom. In this project, we examine the portrayal of robots and labor, a topic that is underexplored in relation to this show. Doctor Who makes for an interesting pop culture case study because, though the show has a huge global fan base, its heart remains in children’s programming. The series originated in 1963 on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a show for children that incorporates lessons related to courage, ingenuity, kindness, and other such qualities, which it continues to do to this day. Doctor Who is also interesting because the Doctor has a history of machines as companions: K-9 the GWENDELYN S. -

Doctor Who Classic Touches Down on Boxing Day

DOCTOR WHO CLASSIC TOUCHES DOWN ON BOXING DAY London, 20 December 2019: BritBox Becomes Home to Doctor Who Classic on 26th December Doctor Who fans across the land get ready to clear their schedules as the biggest Doctor Who Classic collection ever streamed in the UK launches on BritBox from Boxing Day. From 26th December, 627 pieces of Doctor Who Classic content will be available on the service. This tally is comprised of a mix of episodes, spin-offs, documentaries, telesnaps and more and includes many rarely-seen treasures. Subscribers will be able to access this content via web, mobile, tablet, connected TVs and Chromecast. 129 complete stories, which totals 558 episodes spanning the first eight Doctors from William Hartnell to Paul McGann, form the backbone of the collection. The collection also includes four complete stories; The Tenth Planet, The Moonbase, The Ice Warriors and The Invasion, which feature a combination of original content and animation and total 22 episodes. An unaired story entitled Shada which was originally presented as six episodes (but has been uploaded as a 130 minute special), brings this total to 28. A further two complete, solely animated stories - The Power Of The Daleks and The Macra Terror (presented in HD) - add 10 episodes. Five orphaned episodes - The Crusade (2 parts), Galaxy 4, The Space Pirates and The Celestial Toymaker - bring the total up to 600. Doctor Who: The Movie, An Unearthly Child: The Pilot Episode and An Adventure In Space And Time will also be available on the service, in addition to The Underwater Menace, The Wheel In Space and The Web Of Fear which have been completed via telesnaps. -

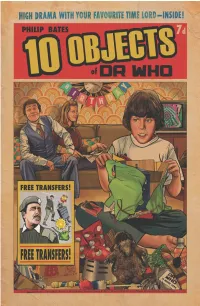

10 Objects of Dr

The right of Philip Bates to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. An unofficial Doctor Who Publication Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2021 Editor: Shaun Russell Editorial: Will Rees Cover and illustrations by Martin Baines Published by Candy Jar Books Mackintosh House 136 Newport Road, Cardiff, CF24 1DJ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Come one, come all, to the Museum of ! Located on the SS. Shawcraft and touring the Seven Systems, right now! Are you a fully-grown human adult? I would like to speak to someone in charge, so please direct me to any children in the vicinity. No, no, that's not fair – I was programmed not to judge, for I am a simple advertisement bot, bringing you the best in junk mail. Are you always that short? No, don’t look at me like that: my creators were from Ravan-Skala, where the people are six hundred ft tall; you have to talk to them in hot air balloons, and the tourist information centre is made of one of their hats.