Dear Mr. President” to Create Conversation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Using Popular Songs to Teach Similes by Thoughtco.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 11.07.17 Word Count 832 Level 940L

What does the timpani sound like? The Timpani in the Orchestra Utah Symphony (6:12) Etude #1, Scherzo by Tom Freer Leonardo Soto, Houston Symphony (2:49) What does a marimba sound like? Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Bach (21 sec.) What does a vibraphone sound like? What does a xylophone sound like? Ode to Joy, Beethoven Excerpt Utah Symphony (18 sec.) (12 sec.) What do tubular bells sound like? What do these instruments sound like? Percussion 101: Chimes BBC National Orchestra of Wales - Percussion Vic Firth (3:03) (1:18) How to Play the Tambourine How to Play the Guiro How to Play the Triangle musicmax.eu (1:03) musicmax.eu (48 sec.) Kalani, Peripole, Inc. (1:58) What do these instruments sound like? Marching Percussion 101: Section Demonstration Chick and a Roll (2:42) Using popular songs to teach similes By ThoughtCo.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 11.07.17 Word Count 832 Level 940L Singer and actress Ariana Grande performing at a concert at the Meadowlands in East Rutherford, New Jersey, in 2014. Photo by: Scott Roth/AP. A simile makes a direct comparison between two things. It uses the words "like" or "as." The comparison reveals a new meaning. For example, the rock group Foreigner wrote a song called "Cold as Ice." The lyrics include a simile: You're as cold as ice You're willing to sacrifice our love In this example, the lyrics are not talking about the weather. Instead, they compare a woman to ice to show her emotions. Many songs can be used to teach about similes. -

The Sociology of Music and Social Distinctions: P!NK's Career As an Example of Social Linkage

Digital Commons @ Assumption University Honors Theses Honors Program 2019 The Sociology of Music and Social Distinctions: P!NK's Career as an Example of Social Linkage David Cifarelli Assumption College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/honorstheses Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cifarelli, David, "The Sociology of Music and Social Distinctions: P!NK's Career as an Example of Social Linkage" (2019). Honors Theses. 49. https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/honorstheses/49 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Digital Commons @ Assumption University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Assumption University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sociology of Music and Social Distinctions: P!NK’s Career as an Example of Social Linkage David Cifarelli Faculty Supervisor: Christopher Gilbert, Ph. D Department of English A Thesis Submitted to Fulfill the Requirements of the Honors Program at Assumption College Spring 2019 Cifarelli 1 Introduction Music is extremely social. It is one of the most expressive art forms our society holds. Due this expressive nature, the art of making music can hold many social connotations and directly involve or relate itself to social occurrences, movements and ideals. This intertwined relationship thus allows music to be a conductor of social change by existing and working within these various social constructs. In addition, those involved with the music-making business are, by association, also potential conductors of social change. -

2020 Community Banking Study

FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION FDIC Community Banking Study December 2020 Table of Contents Foreword . I Acknowledgements . III Executive Summary . V Chapter 1: Community Bank Financial Performance . .. 1-1 Chapter 2: Structural Change Among Community and Noncommunity Banks . 2-1 Chapter 3: The Effects of Demographic Changes on Community Banks . 3-1 Chapter 4: Notable Lending Strengths of Community Banks . 4-1 Chapter 5: Regulatory Change and Community Banks . 5-1 Chapter 6: Technology in Community Banks . 6-1 Bibliography . i Appendix A: Study Definitions . A-1 Appendix B: Selected Federal Agency Actions Affecting Community Banks, 2008–2019 . B-1 FDIC COMMUNITY BANKING STUDY ■ DECEMBER 2020 Foreword Eight years ago, coming out of the financial crisis, the throughout this country, which is why I made this update FDIC conducted a study of community banks. This study to the 2012 Community Banking Study a research priority was the first large-scale review of community banks ever in 2020. I instructed my research team not only to update conducted, and it recognized the importance of community key aspects of the prior study, but also to consider new banks and their unique role in the banking industry. As topics that are important to community banks, such a result of that study, the FDIC changed its approach to as regulatory change and technology. By continuing to identifying community banks. In general, community study community banks and providing that research banks are those that provide traditional banking services to the public—our stakeholders—we can continue to in their local communities. As of year-end 2019, there were identify ways that the FDIC can provide support to 4,750 community banks in the country with more than these institutions. -

Jazz – Pop – Rock Gesamtliste Stand Januar 2021

Jazz – Pop – Rock Gesamtliste Stand Januar 2021 50 Cent Thing is back CD 1441 77 Bombay Str. Up in the Sky CD 1332 77 Bombay Street Oko Town CD 1442 77 Bombay Street Seven Mountains CD 1684 7 Dollar Taxi Bomb Shelter Romance CD 1903 Abba The Definitive Collection CD 1085 Abba Gold CD 243 Abba (Feat.) Mamma Mia! Feat. Abba CD 992 Above & Beyond We are all we need CD 1643 AC/DC Black Ice CD 1044 AC/DC Rock or Bust CD 1627 Adams, Bryan Tracks of my Years CD 1611 Adams, Bryan Reckless CD 1689 Adele Adele 19 CD 1009 Adele Adele: 21 CD 1285 Adele Adele 25 CD 1703 Aguilera, Christina Liberation CD 1831 a-ha 25 Twenty Five CD 1239 Airbow, Tenzin Reflecting Signs CD 1924 Albin Brun/Patricia Draeger Glisch d’atun CD 1849 Ali Erol CD 1801 Allen, Lily It’s not Me, it’s You CD 1550 Allen, Lily Sheezus CD 1574 Alt-J An Awsome Wave CD 1503 Alt-J This is all yours CD 1637 Alt-J This is all yours, too CD 1654 Amir Au Cœurs de moi CD 1730 Girac, Kendji Amigo CD 1842 Anastacia Heavy rotation CD 1301 Anastacia Resurrection CD 1587 Angèle Brol la Suite CD 1916 Anthony, Marc El Cantante CD 1676 Arctic Monkeys Whatever people say CD 1617 Armatrading, Joan Starlight CD 1423 Ärzte, Die Jazz ist anders CD 911 Aslan Hype CD 1818 Avicii Tim CD 1892 Avidan, Assaf Gold Shadow CD 1669 Azcano, Juli Distancias CD 1851 Azcano, Julio/Arroyo, M. New Tango Songbook CD 1850 Baba Shrimps Neon CD 1570 Baker, Bastian Tomorrow may not be better CD 1397 Baker, Bastian Noël’s Room CD 1481 Baker, Bastian Too old to die young CD 1531 Baker, Bastian Facing Canyons CD 1702 Bailey Rae, Corinne The Heart speaks in Whispers CD 1733 Barclay James H. -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

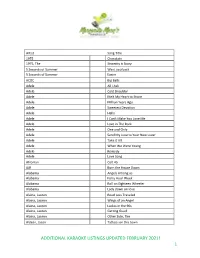

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

The Music Column That Wouldn't Die: New Album Reviews

The Music Column That Wouldn’t Die: New Album Reviews. I told myself I was over this, that I had retired from the world of music reviews. I had moved onto bigger and better things (mostly staring at the wall and wondering why nobody calls me anymore). Yet here I am, a mere few months after burning my bridges, giving up on new music and making a world of enemies, back in the game. Did I miss the constant abuse, the being paid in soiled pennies and the lack of recognition which writing this unremembered column entailed? Funnily enough, I did! It was listening to the post punk genius of the new Dry Cleaning record that did it. I thought to myself ‘someone has to take it upon themselves to tell the world just how good this album is’. After a moment of quiet reflection where I drank a glass of lukewarm Ribena to calm the nerves, I decided that that person may as well be me. By JOHN BITTLES So, here we are. Bittles’ Magazine, like some particularly bothersome zombie with a bad haircut and worse breath, has been reborn. And what a re-introduction we have! In this month’s reviews there is the art heavy punk funk strut of Squid, the melancholy dream pop of White Flowers, Thomas Fehlmann’s rich ambiance, the return of living legends The Coral, the skewed pop of Dntel, and Dry Cleaning of course. So, tell all your friends, phone the tabloids, and let us begin… New Long Leg by Dry Cleaning. -

Reviewing Romcom: (100) Imdb Users and (500) Days of Summer

. Volume 8, Issue 2 November 2011 Reviewing Romcom: (100) IMDb Users and (500) Days of Summer Inger-Lise Kalviknes Bore Birmingham City University, UK Abstract This article contributes to academic debates around the romantic comedy genre and comedy audiences by examining IMDb user reviews of (500) Days of Summer (2009). Directed by Marc Webb for Fox Searchlight Pictures, (500) Days of Summer was promoted with the tagline ‘Boy meets girl. Boy falls in love. Girl doesn’t’. This presents the film as an unconventional romantic comedy in at least three ways: Firstly, it suggests that these two characters will not actually end up together, which challenges the idea of the romcom couple as ‘meant to be’. Secondly, it presents the possibility that audiences might not get the happy ending we usually expect from comedy. And finally, the tagline casts the boy, rather than the girl, in the role as yearning romantic, thereby challenging the traditional gender roles of heterosexual relationships. So how did audiences respond to this film? At the time of writing, it has been rated by 75,716 IMDb users, and has an average score of 8.0 out of 10. This clearly suggests a favourable reception, but the IMDb reviews also offer qualitative data that can shed further light on how the film has been evaluated. What kinds of criteria are in operation? What elements do reviewers highlight as important for their experiences of the film? How is the film seen to fail for some viewers? Drawing on previous studies of romantic comedy, the analysis will consider how these particular audience members articulated their responses to (500) Days of Summer, as well as their positions as reviewers. -

Hurts 2B Human" Uscirà Il 26 Aprile Per RCA Records Ed È Disponibile Per Il Pre-Order Già Da Oggi

GIOVEDì 28 MARZO 2019 L'ottavo album di P!NK "Hurts 2b Human" uscirà il 26 aprile per RCA Records ed è disponibile per il pre-order già da oggi. Per festeggiare, la popstar pubblica anche un altro pezzo contenuto nell'album, "Hustle", P!NK, esce il 26 aprile il nuovo scritto dalla stessa P!NK insieme a Dan Reynolds degli Imagine Dragons album "Hurts 2b Human" e a Jorgen Odegard e prodotto da Odegard (con la collaborazione di Reynolds). Le 13 tracce vedono P!NK collaborare di nuovo con i suoi fidati collaboratori Max Martin, Shellback, Julia Michaels, Nate Ruess, Greg Kurstin, Billy Mann e per la prima volta con Teddy Geiger, Sasha Sloan, CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Beck e Sia, oltre ai featuring con Khalid, Chris Stapleton, Cash Cash e Wrabel. Il primo singolo ora in radio "Walk Me Home" ha più di 50 milioni di stream in tutto il mondo e rimane nella top 10 di iTunes US. Il video diretto da Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman) e da Stuart Bowen, uscito settimana scorsa, ha più di 6 milioni di views. [email protected] SPETTACOLINEWS.IT La cantante americana ha da poco dato il via alla seconda tranche del suo Beautiful Trauma World Tour a partire dal 1 marzo da Sunrise, in Florida, e terminerà con ben due serate al New York City's Madison Square Garden il 21 e il 22 maggio. Per il tour sono già stati venduti più di 3 milioni di biglietti in tutto il mondo e più di 1 milione solo in America. Dal suo debutto nel 2000, P!NK (Alecia Moore) ha pubblicato 6 album ("Can't Take Me Home", "M!ssundaztood", "Try This", "I'm Not Dead", "Funhouse", "Greatest Hits So Far!!!"), venduto oltre 60 milioni di album, 75 milioni di singoli (quasi 20 milioni di brani digitali), più di 2.4 milioni di DVD in tutto il mondo e ha avuto ben 15 singoli nella top 10 della classifica Hot 100 di Billboard. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Limitations on Copyright Protection for Format Ideas in Reality Television Programming

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING By Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen* * Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen are partners in the Entertainment, Media, and Technology Group in the Century City, California and Washington, D.C. offices, respectively, of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP. The authors thank Ben Aigboboh, an associate in the Century City office, for his assistance with this article. 97 For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I. INTRODUCTION Television networks constantly compete to find and produce the next big hit. The shifting economic landscape forged by increasing competition between and among ever-proliferating media platforms, however, places extreme pressure on network profit margins. Fully scripted hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies have become increasingly costly, while delivering diminishing ratings in the key demographics most valued by advertisers. It therefore is not surprising that the reality television genre has become a staple of network schedules. New reality shows are churned out each season.1 The main appeal, of course, is that they are cheap to make and addictive to watch. Networks are able to take ordinary people and create a show without having to pay “A-list” actor salaries and hire teams of writers.2 Many of the most popular programs are unscripted, meaning lower cost for higher ratings. Even where the ratings are flat, such shows are capable of generating higher profit margins through advertising directed to large groups of more readily targeted viewers.