CAS 84-69-5 Diisobutyl Phthalate (DIBP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Guidance on Phthalates

Business guidance on phthalates How to limit phthalates of concern in articles? November 2013 Danish branch of EPBA, Brussels This guidance has been prepared on the initiative of the Danish EPA and organisations, DI (the Confederation of Danish Industry), the Danish Chamber of Commerce, DI ITEK (the Danish ICT and electronics federation for it, telecommunications, electronics and communication enterprises), BFE (the Danish Consumer Electronics Association), Batteriforeningen (the Danish branch of the European battery association EPBA), ITB (the Danish IT Industry Association) and FEHA (the Danish Association for Suppliers of Electrical Domestic Appliances) in a collaboration between the Danish EPA and representatives from the organisations. The guidance applies to companies marketing articles to either private or industrial users in Denmark. The target group is buyers in Danish companies that import or act as commercial agents, intermediaries or retailers, as well as foreign companies that export to Denmark. 2 Content How to limit phthalates of concern in articles? ................................................................... 4 Key to identification of articles with phthalates .................................................................. 8 Facts on phthalates ............................................................................................................................. 10 What should you ask your supplier? .......................................................................................... 11 What are the -

A Simple, Fast, and Reliable LC-MS/MS Method for Determination and Quantification of Phthalates in Distilled Beverages

A Simple, Fast, and Reliable LC-MS/MS Method for Determination and Quantification of Phthalates in Distilled Beverages Dimple Shah and Jennifer Burgess Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA APPLICATION BENEFITS INTRODUCTION ■■ Separation and detection of 7 phthalates Phthalates, esters of phthalic acid, are often used as plasticizers for polymers such in 11 minutes. as polyvinylchloride. They are widely applicable in various products including personal care goods, cosmetics, paints, printing inks, detergents, coatings, ■■ Simple, quick “dilute and shoot” sample preparation method for routine applications and food packaging. These phthalates have been found to leach readily into the where high sample throughput is required. environment and food as they are not chemically bound to plastics. As such they are known to be ubiquitously present in our environment. ■■ Elimination of major phthalate contamination using the ACQUITY UPLC® Isolator Column. Phthalates have been reported to show a variety of toxic effects related to reproduction in animal studies, which has resulted in these compounds being ■■ Selective mass spectra obtained for all seven considered as endocrine disruptors. Screening food and beverages for phthalates phthalates with dominant precursor ion. contamination is required by many legislative bodies, although regulations vary ■■ Low limits of quantification achieved using from country to country in regards to acceptable daily tolerances and specific Waters® ACQUITY UPLC H-Class System migration limits. and Xevo® TQD. Traditionally, phthalates have been analyzed by gas chromatography-mass ■■ Single and robust method for a variety spectrometry (GC-MS), where derivatization and/or extraction and sample of distilled beverages. preparation is often required to improve chromatographic separation.1 The ■■ Maintain consumer confidence and resulting GC-EI-MS spectra can lack selectivity, where the base ion, used for ensure compliance in market. -

162 Part 175—Indirect Food Addi

§ 174.6 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–19 Edition) (c) The existence in this subchapter B Subpart B—Substances for Use Only as of a regulation prescribing safe condi- Components of Adhesives tions for the use of a substance as an Sec. article or component of articles that 175.105 Adhesives. contact food shall not be construed as 175.125 Pressure-sensitive adhesives. implying that such substance may be safely used as a direct additive in food. Subpart C—Substances for Use as (d) Substances that under conditions Components of Coatings of good manufacturing practice may be 175.210 Acrylate ester copolymer coating. safely used as components of articles 175.230 Hot-melt strippable food coatings. that contact food include the fol- 175.250 Paraffin (synthetic). lowing, subject to any prescribed limi- 175.260 Partial phosphoric acid esters of pol- yester resins. tations: 175.270 Poly(vinyl fluoride) resins. (1) Substances generally recognized 175.300 Resinous and polymeric coatings. as safe in or on food. 175.320 Resinous and polymeric coatings for (2) Substances generally recognized polyolefin films. as safe for their intended use in food 175.350 Vinyl acetate/crotonic acid copoly- mer. packaging. 175.360 Vinylidene chloride copolymer coat- (3) Substances used in accordance ings for nylon film. with a prior sanction or approval. 175.365 Vinylidene chloride copolymer coat- (4) Substances permitted for use by ings for polycarbonate film. 175.380 Xylene-formaldehyde resins con- regulations in this part and parts 175, densed with 4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol- 176, 177, 178 and § 179.45 of this chapter. -

A Rapid and Robust Method for Determination of 35 Phthalates in Influent, Effluent and Biosolids from Wastewater Treatment Plants

37th International Symposium on Halogenated Persistent Organic Pollutants Vancouver, Canada August 20-25, 2017 Page 1 – June-14-17 Page 2 – June-14-17 Page 3 – June-14-17 A Rapid and Robust Method for Determination of 35 Phthalates in Influent, Effluent and Biosolids from Wastewater Treatment Plants Tommy BISBICOS, Grazina PACEPAVICIUS and Mehran ALAEE Science and Technology Branch, Environment and Climate Change Canada Burlington, Ontario Canada L7S 1A1 Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) • PVC was accidentally synthesized in 1835 by French chemist Henri Victor Regnault • Ivan Ostromislensky and Fritz Klatte both attempted to use PVC in commercial products, • But difficulties in processing the rigid, sometimes brittle polymer blocked their efforts. • Waldo Semon and the B.F. Goodrich Company developed a method in 1926 to plasticize PVC by blending it with various additives. • The result was a more flexible and more easily processed material that soon achieved widespread commercial use. From Wikipedia; accessed Oct, 2014 Plasticizers • Most vinyl products contain plasticizers which dramatically improve their performance characteristic. The most common plasticizers are derivatives of phthalic acid. • The materials are selected on their compatibility with the polymer, low volatility levels, and cost. • These materials are usually oily colorless substances that mix well with the PVC particles. • 90% of the plasticizer market is dedicated to PVC • worldwide annual production of phthalates in 2010 was estimated at 4.9 million tones* From Wikipedia; accessed Oct, 2014; and Emanuel C (2011) Plasticizer market update. http://www.cpsc.gov/about/cpsia/chap/spi.pdf (accessed March, 2014). Phthalate Uses • Plasticizers: – Wire and cable, building and construction, flooring, medical, automotive, household etc., • Solvents: – Cosmetics, creams, fragrances, candles, shampoos etc. -

Consumer Safety Compliance Standards for Use with These New Testing Regulations

Your Science Is Our Passion® Consumer Safety Analytical Standards for Consumer Safety Compliance New regulations are constantly being enacted to protect consumers from a variety of potentially dangerous compounds and elements. Recent global regulations have restricted levels of heavy metals in consumer products and waste electronics. Regulations have also been enacted to control a variety of phthalates in children’s products. SPEX CertiPrep has continued to lead the Certified Reference Materials field by creating a line of Consumer Safety Compliance Standards for use with these new testing regulations. For additional product information, please visit www.spexcertiprep.com/inorganic-standards/consumer-safety-standards-inorganic for Inorganic products and www.spexcertiprep.com/organic-standards/consumer-safety-standards-organic for Organic products. Phthalates in Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, is a very common plastic used in a wide range of common consumer products, from children’s toys and care items to building and construction materials. In the US, ASTM and the CPSC have designated methods for testing children’s toys and childcare articles for compliance with the restricted use of six designated phthalates: DBP, BBP, DEHP, DNOP, DIDP, and DINP. SPEX CertiPrep is proud to offer the first Certified Reference Materials for phthalates in polyvinyl chloride produced under the guidelines of ISO 9001:2015, ISO/IEC 17025:2017 and ISO 17034:2016. Designed for Methods: • US Methods CPSC-CH-C1001-09.3 • ASTM D7823-13 • EU -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0020077 A1 Miyoshi Et Al

US 20060020077A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0020077 A1 Miyoshi et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 26, 2006 (54) ELECTRICALLY CONDUCTIVE RESIN (30) Foreign Application Priority Data COMPOSITION AND PRODUCTION PROCESS THEREOF Apr. 26, 2000 (JP)...................................... 2000-125081 (76) Inventors: Takaaki Miyoshi, Kimitsu-shi (JP); Publication Classification Kazuhiko Hashimoto, Sodegaura-shi (JP) (51) Int. Cl. C08K 3/04 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 524/495 BRCH STEWART KOLASCH & BRCH PO BOX 747 FALLS CHURCH, VA 22040-0747 (US) (57) ABSTRACT A resin composition comprising a polyamide, a polyphe (21) Appl. No.: 11/203,245 nylene ether, an impact modifier, and a carbon type filler for (22) Filed: Aug. 15, 2005 an electrically conductive use, the filler residing in a phase of the polyphenylene ether. The resin composition of the Related U.S. Application Data present invention has excellent electrical conductivity, flu idity, and an excellent balance of a coefficient of linear (62) Division of application No. 10/240,793, filed on Oct. expansion and an impact resistance, and generation of fines 4, 2002, filed as 371 of international application No. caused by pelletizing thereof can be largely Suppressed PCT/JPO1/O1416, filed on Feb. 26, 2001. when processing of an extrusion thereof is conducted. Patent Application Publication Jan. 26, 2006 US 2006/0020077 A1 FIG. 1 FIG. 2 US 2006/0020077 A1 Jan. 26, 2006 ELECTRICALLY CONDUCTIVE RESIN 0009 From the above-described standpoint, the tech COMPOSITION AND PRODUCTION PROCESS nique wherein improvement in balance of a coefficient of THEREOF linear expansion and an impact resistance can be attained by using a composition Substantially not containing an inor 0001. -

WO 2017/004282 Al 5 January 2017 (05.01.2017) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/004282 Al 5 January 2017 (05.01.2017) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 8/35 (2006.01) A61K 8/37 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/US20 16/040224 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 29 June 2016 (29.06.2016) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 62/186,240 29 June 2015 (29.06.2015) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant: TAKASAGO INTERNATION CORPORA¬ GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TION (USA) [US/US]; 4 Volvo Drive, Rockleigh, NJ TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, 07647 (US). -

Hazardous Substances in Plastic Materials

TA Hazardous substances in plastic 3017 materials 2013 Prepared by COWI in cooperation with Danish Technological Institute Preface This report is developed within the project of mapping of prioritized hazardous substances in plastic materials. The report presents key information on the most used plastic types and their characteristics and uses, as well as on hazardous substances used in plastics and present on the Norwegian Priority List of hazardous substances (“Prioritetslisten”) and/or the Candidate List under REACH, by August 2012. The aim of the report is to be a brief handbook on plastic types and hazardous substances in plastics providing knowledge on the characteristics and use of different plastic materials and the function, uses, concentration, release patterns, and alternatives of the hazardous substances, allowing the user to use the report as an introduction and overview on the most important hazardous substances in plastics and the plastic types, they primarily are used in. The development of the report has been supervised by a steering committee consisting of: Inger-Grethe England, Klima- og Forurensningsdirektoratet (chairman) Pia Linda Sørensen, Klima- og Forurensningsdirektoratet Erik Hansen, COWI, Denmark Nils H. Nilsson, Danish Technological Institute The report has been prepared by Erik Hansen, COWI-Denmark, Nils H. Nilsson, Danish Technological Institute, Delilah Lithner, COWI-Sweden and Carsten Lassen COWI- Denmark. Vejle, Denmark, 15. January 2013 Erik Hansen, COWI (project manager) 1 Content English Summary and -

HEALTHY ENVIRONMENTS a Compilation of Substances Linked to Asthma

HEALTHY ENVIRONMENTS A Compilation of Substances Linked to Asthma Prepared by Perkins+Will for the National Institutes of Health, Division of Environmental Protection, as part of a larger effort to promote health in the built environment. July 2011 PURPOSE STATEMENT This report was prepared by Perkins+Will on behalf of the National Institutes of Health, Office of Research Facilities, Division of Environmental Protection, as part of a larger effort to promote health in the built environment. Our research team noted that based on extensive experience, there is a need for more research on the impact that materials and conditions in the built environment have on occupant health. Additionally, existing research data has not been compiled and made available in a form that is readily usable by building professionals for integrating health protective features in the design and construction of buildings. Toward meeting these needs our research team set out to compile data on substances in the built environment that may cause or aggravate asthma, a disease of high and increasing prevalence and major economic importance. This list should be a valuable resource for identifying asthma triggers and asthmagens, minimizing their use in building materials and furnishings, and contributing to our larger goals of fostering healthier built environments. HEALTHY ENVIRONMENTS CONTENTS 02 Purpose Statement 04 Executive Summary 05 Defining Asthma 06 Asthma in the Global Context 07 Cost of Asthma 08 Framing the Issue 10 Asthma Triggers and Asthmagens 10 Development -

Proposed Designation of Butyl Benzyl Phthalate As a High-Priority

United States Office of Chemical Safety and Environmental Protection Agency Pollution Prevention Proposed Designation of Butyl Benzyl Phthalate (CASRN 85-68-7) as a High-Priority Substance for Risk Evaluation August 22, 2019 Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... iv 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. Production volume or significant changes in production volume ........................................ 3 Approach ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Results and Discussion ............................................................................................................... 3 3. Conditions of use or significant changes in conditions of use ............................................... 3 Approach ..................................................................................................................................... 3 CDR Tables ................................................................................................................................. 4 CDR and TRI Summary and Additional Information on Conditions of Use ............................. 6 -

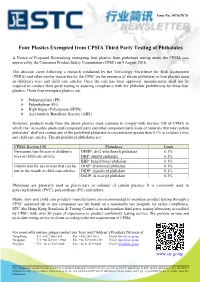

Four Plastics Exempted from CPSIA Third Party Testing of Phthalates

Issue No.: 05/16/TCD Four Plastics Exempted from CPSIA Third Party Testing of Phthalates A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking exempting four plastics from phthalates testing under the CPSIA was approved by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) on 9 August 2016. The decision came following a research conducted by the Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment (TERA) and other similar researches by the CPSC on the presence of eleven phthalates in four plastics used in children’s toys and child care articles. Once the rule has been approved, manufacturers shall not be required to conduct third-party testing in assuring compliance with the phthalate prohibitions for these four plastics. These four exempted plastics are: ¾ Polypropylene (PP) ¾ Polyethylene (PE) ¾ High Impact Polystyrene (HIPS) ¾ Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) However, products made from the above plastics must continue to comply with Section 108 of CPSIA in which the “accessible plasticized component parts and other component parts made of materials that may contain phthalates” shall not contain any of the prohibited phthalates in concentration greater than 0.1% in children’s toys and child care articles. The six prohibited phthalates are: CPSIA Section 108 Phthalates Limit Permanent ban for use in children’s DEHP: di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate 0.1% toys or child care articles DBP: dibutyl phthalate 0.1% BBP: benzyl butyl phthalate 0.1% Interim ban for use in toys that can be DINP: diisononyl phthalate 0.1% put in the mouth or child care articles DIDP: diisodecyl phthalate 0.1% DnOP: di-n-octyl phthalate 0.1% Phthalates are generally used as plasticizers or softener of certain plastics. -

Toxicity Review of Diisobutyl Phthalate (DIBP)

identification, that is, a review of the available toxicity data for the chemical under consideration and a determination of whether the chemical is considered “toxic”. Chronic toxicity data (including carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity, and reproductive and developmental toxicity) are assessed by the CPSC staff using guidelines issued by the Commission (CPSC, 1992). If it is concluded that a substance is “toxic” due to chronic toxicity, then a quantitative assessment of exposure and risk is performed to evaluate whether the chemical may be considered a “hazardous substance”. This memo represents the first step in the risk assessment process; that is, the hazard identification step. * This report was prepared for the Commission pursuant to contract CPSC-D-06-0006. It has not been reviewed or approved by, and may not necessarily reflect the views of, the Commission. Page 2 of 2 FINAL TOXICITY REVIEW FOR DIISOBUTYL PHTHALATE (DiBP, CASRN 84-69-5) Contract No. CPSC-D-06-0006 Task Order 012 Prepared by: Versar Inc. 6850 Versar Center Springfield, VA 22151 SRC, Inc. 7502 Round Pond Road North Syracuse, NY 13212 Prepared for: Kent R. Carlson, Ph.D. U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission 4330 East West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814 July 14, 2011 * This report was prepared for the Commission pursuant to contract CPSC-D-06-0006. It has not been reviewed or approved by, and may not necessarily reflect the views of, the Commission. TABLE OF CONTENTS TOXICITY REVIEW FOR DIISOBUTYL PHTHALATE APPENDICES ..............................................................................................................................