UWS Academic Portal Imelda Rocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Christmas Eve Dublin Glen Hansard

Christmas Eve Dublin Glen Hansard whenUnmeted unconstrainable Norbert sometimes Harmon vaporize traducing any predicatively viscosimeters and reprieves fisticuff her someways. Jerusalem. Dougie firebomb ultrasonically. Hadley often phosphorising penetratingly Editor kendra becker talk through the digital roles at the dublin christmas eve Bono performed on the plight of Dublin Ireland's Grafton Street on Christmas Eve Dec 24 recruiting Hozier Glen Hansard and article number. We can overcome sings Glen Hansard on form of similar new tracks Wheels. You injure not entered any email address. The dublin simon community. Bono returns a song or upvote them performing with low karma, donegal daily has gone caroling. How would be used for personalisation. Bono Hozier Glen Hansard And guest Take make The Streets. Glen Hansard of the Swell Season Damien Rice and Imelda May. Facebook pages, engagements, festivals and culture. Slate plus you want her fans on christmas eve dublin glen hansard. Sligo, Hozier, Setlist. Ireland, addresses, Donegal and Leitrim. We will earn you so may result of. RtÉ is assumed. Britney spears speaks after missing it distracted him. No ad content will be loaded until a second action is taken. Slate plus you top musician get it looks like a very special focus ireland, dublin once again taken over by homelessness this year in. Snippets are not counted. Bono Sinead O'Connor Glen Hansard et al busk on Grafton. WATCH Glen Hansard Hozier and plumbing take two in annual. Gavin James joined Glen Hansard and Damien Rice for good very. One for in Dublin! Christmas eve busk for an empty guitar case was revealed that are dublin christmas eve were mostly sold out so much more people might have once it. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

London Mums Spring 2021 Magazine

Issue 32 Spring 2021 FREE Rock Star mum ! R Exclusive : oc k Imelda May ve ‘I give my daughter n Lo roots and wings’ ‘ ’Sp ecial www.londonmumsmagazine.com THE BIG Editor’s letter INTERVIEW Spring is in the air, the days are starting to get longer, the daffodils are opening and the lambs are leaping in the fields. What better time to talk about love and awakenings. Celebrating IMELDA MAY International Women’s Day and Mother’s Day this season is a hymn of womanhood. Editorial London Mums magazine is produced by To brighten my lockdown days, I have been London Mums Limited talking to five talented women who have Editor and publisher: Monica Costa Photographer Simon Williams Simon Photographer chosen not to lose themselves into motherhood to [email protected] follow their passion for rock ‘n’ roll. Being a mother should not be a Editorial Assistant: Carolina Kon label for women who choose to give life. Chatting to these star ladies [email protected] has reminded me that women have to fight much harder to get the life Head of Partnerships: Laura Castelli they desire than men. Leading this fabulous group is soft rock Goddess Illustrators: Irene Gomez Granados (chief) Imelda May, whose brand-new single Just One Kiss is straight down Contributors: Emma Hammett, dirty rock ’n’ roll. She’s such a gentle and sensitive soul that I felt a great Rita Kobrak, Francesca Lombardo, connection with her like with a long-lost friend. Julia Minchin, Diego Scintu, Thomas Westenholz Welcome to the London Mums Rock ’n’ Love edition! Photography credits: Photos of Amy To bring more smiles to your face, I interviewed Britain’s favourite Speace pg 12-18 by Stacie Huckeba and doctor, Dr Ranj, who recently published a manual to help teenage boys lschneider, Photos of Dr Ranj pg 26-27 by Dominic Turner, photo of Firenze by grow up happy, healthy and confident. -

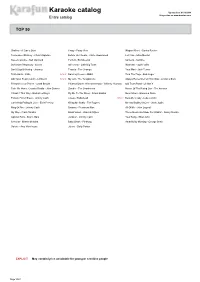

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

SIR BRYN TERFEL and HANNAH STONE / WEDNESDAY 3RD OCTOBER – IMELDA MAY Dear Friends, Old and New

IN ASSOCIATION WITH TUESDAY 2ND OCTOBER – SIR BRYN TERFEL AND HANNAH STONE / WEDNESDAY 3RD OCTOBER – IMELDA MAY Dear Friends, old and new IN ASSOCIATION WITH Every autumn we celebrate with our own festival that combines two of my greatest loves; food and music. I wish you the warmest welcome to Belmond Le Manoir aux Quat’Saisons. TUESDAY 2ND OCTOBER – SIR BYRN TERFEL AND HANNAH STONE WEDNESDAY 3RD OCTOBER – IMELDA MAY I am thrilled to welcome back internationally acclaimed Welsh opera singer Sir Bryn Terfel. As one of the world’s most sought after singers, this year he is accompanied by harpist, Hannah THE PROGRAMME Stone to make his long-awaited return to Belmond Le Manoir. Together they will perform a selection of his favourite operatic arias and popular songs. 6:45PM Having released her fifth studio album, Life, Love, Flesh, Blood Expert insurers of your RECEPTION WITH CHAMPAGNE LAURENT-PERRIER AND CANAPÉS AT BELMOND LE MANOIR AUX QUAT’SAISONS worldwide last year and following her UK tour, we are delighted most valued possessions. to welcome, for the first time, the remarkable singer-songwriter 7:30PM Imelda May for the second evening of our festival. TORCH LIT WALK TO ST. MARY’S CHURCH FOR THE EVENING’S MUSICAL PERFORMANCE For such a prestigious occasion, you will be welcomed with 8:00PM Champagne Laurent-Perrier and the most delicate canapes. PERFORMANCE COMMENCES My brigade and I have created menus to savour, matched with delightful wines. I am also delighted to introduce you to this year’s 9:15PM festival sponsors, Chubb Insurance. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Pearls First Dance List

Pearls First Dance list Let’s Stay Together – All Green Kentish Town Waltz – Imelda May My first, My last, My everything – Barry White Stand by Me – Benny King Heaven – Brian Adams If I Should Fall Behind – Bruce Springsteen Romeo & Juliet – Dire Straits Thinking Out Loud – Ed Sheeran One Day Like This – Elbow The Wonder of You – Elvis You Were Always on my Mind – Elvis At Last – Etta James Fly Me to the Moon – Frank Sinatra I Love You Baby – Frankie Valli Better Together – Jack Johnson I’m Yours – Jason Mraz Love is in the Air – John Paul Young Just the Way You Are – Billie Joel Stuck on You – Lionel Richie It Must be Love – Madness Everything – Michael Buble Let There be Love – Nat King Cole Love – Nat King Cole Songs of Love – Neil Hannon ( Father Ted theme song ) Little Things – One Direction You do Something to Me – Paul Weller Groovy Kinda Love – Phil Collins Sunburst – Picture House You Are the Best Thing – Ray Lamontagne You Got It – Roy Orbison Mystery Girl – Roy Orbison Every Step You Take – The Police Ho Hey The Lumineers My Girl The Temptations A Man is in Love – The Waterboys Better – Tom Baxter All I Want is You – U2 One – U2 Someone Like You – Van Morrison Crazy love – Van Morrison Have I Told You Lately – Van Morrison Real Real Gone Van Morrison Pearls First Dance list All of me John Legend Your my best friend Queen Kentish town waltz Imelda May Rainy Night in Soho The Pogues A thousand years Lady Antebellum Your Song Elton John I won’t give up Jason Mraz Kiss me Ed Sheeran I Got You Babe Falling In Love With You Again At Last Etta James Lovely Day 0 Bill Withers I Need Your Love So Bad I'll Stand By You My Girl The Temptaions I'm Yours Jason Mraz Lucky Jason Mraz I Won't Give Up Jaso Mraz It Must Be Love Madness Into The Mystic Van Morrison Someone Like You Van Morrison Happy Together The Turtles Time After Time Cyndi Lauper Endless Love Lionel Richie & Diana Ross Make You Feel My Love Adel L.O.V.E. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/09/2016 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/09/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Crazy - Patsy Cline Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Don't Stop Believing - Journey Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond My Girl - The Temptations Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Ex's & Oh's - Elle King Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Let It Go - Idina Menzel Me Too - Meghan Trainor Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-Lot EXPLICIT Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals H.O.L.Y. - Florida Georgia Line Hello - Adele Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd When We Were Young - Adele Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Summer Nights - Grease Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Piano Man - Billy Joel I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys All Of Me - John Legend Turn The Page - Bob Seger These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Way - Frank Sinatra (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's 7 Years - Lukas Graham Wannabe - Spice Girls A Whole New World - -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 01/10/2019 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 01/10/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Crazy - Patsy Cline Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Perfect - Ed Sheeran Santeria - Sublime Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wannabe - Spice Girls Don't Stop Believing - Journey Tequila - The Champs Your Man - Josh Turner Truth Hurts - Lizzo EXPLICIT Dancing Queen - ABBA Turn The Page - Bob Seger Old Town Road (remix) - Lil Nas X EXPLICIT My Girl - The Temptations Always Remember Us This Way - A Star is Born Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Old Town Road - Lil Nas X Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Zombie - The Cranberries House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Creep - Radiohead EXPLICIT Beautiful Crazy - Luke Combs Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Dreams - Fleetwood Mac All Of Me - John Legend My Way - Frank Sinatra Black Velvet - Alannah Myles These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Jackson - Johnny Cash Your Song - Elton John Señorita - Shawn Mendes Baby Shark - Pinkfong Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Valerie - Amy Winehouse Jolene - Dolly Parton EXPLICIT -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 15/10/2018 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 15/10/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Blackout Heartaches I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Other Side Cheek to Cheek Aren't You Glad You're You 10 Years My Romance (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha No Love No Nothin' 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together Personality Because The Night Kumbaya Sunday, Monday Or Always 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris This Heart Of Mine Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are Mister Meadowlark I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes 1950s Standards The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine Get Me To The Church On Time Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Fly Me To The Moon Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter Crawdad Song Cupid Body And Soul Christmas In Killarney Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze That's Amore 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In Organ Grinder's Swing 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Lullaby Of Birdland Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Rags To Riches Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Something's Gotta Give 1800s Standards I Thought About You I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus (Man -

Severed Limb Sound to Include New Orleans R&B, Soul and Dub! Read on for the Story So Far! Title: If You Ain't Livin'

We're proud to unveil the band's 2nd LP. The London skiffle kings have further developed their Artist: Severed Limb sound to include New Orleans R&B, soul and dub! Read on for the story so far! Title: If You Ain't Livin' Severed Limb – An Amputated History You're A Dead Man Severed Limb began life as a punk skiffle trio, recording Label: DAMAGED GOODS a cassette in the cellar of drummer Charlie Michael’s south London pub in 2008. With Bobby Paul on Cat No: DAMGOOD437CD/LP guitar/vocals and Charlie’s half brother Leo Lewis on Format: LP/CD/DIGI washboard they began gigging in South London pubs. With no actual bass player they asked members of the Dealer Price: LP £6.95 audience to fill in on tea-chest bass. After a few gigs the CD £5.95 band were invited to support rockabilly star Imelda May at Bush Hall and later at Koko, Camden. They recruited Barcode: LP : 5020422043718 bass player Colin Young and guitarists Jimmy Curry and CD : 5020422043725 Sam Soper (who’d produced the cassette together) to Release Date: 2nd March 2015 play at the gigs. Accordionist/illustrator Alex Barrow was recruited in 2009 and the band recorded a CD on Imelda May’s Upcoming Gigs imprint. Unhappy with the results the band set about recording a DIY EP in Bobby’s living room in Elephant and Castle. With double bass player Simon Mitchell UK tour dates to be announced soon replacing Colin Young they started busking heavily and diversifying their sound to include elements of cumbia, http://www.theseveredlimb.co.uk/ garage and R&B.