Raya Bodnarchuk This Is a True Picture of How It Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gyã¶Rgy Kepes Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80r9v19 No online items Guide to the György Kepes papers M1796 Collection processed by John R. Blakinger, finding aid by Franz Kunst Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2016 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the György Kepes M1796 1 papers M1796 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: György Kepes papers creator: Kepes, Gyorgy Identifier/Call Number: M1796 Physical Description: 113 Linear Feet (108 boxes, 68 flat boxes, 8 cartons, 4 card boxes, 3 half-boxes, 2 map-folders, 1 tube) Date (inclusive): 1918-2010 Date (bulk): 1960-1990 Abstract: The personal papers of artist, designer, and visual theorist György Kepes. Language of Material: While most of the collection is in English, there is also a significant amount of Hungarian text, as well as printed material in German, Italian, Japanese, and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Biographical / Historical Artist, designer, and visual theorist György Kepes was born in 1906 in Selyp, Hungary. Originally associated with Germany’s Bauhaus as a colleague of László Moholy-Nagy, he emigrated to the United States in 1937 to teach Light and Color at Moholy's New Bauhaus (soon to be called the Institute of Design) in Chicago. In 1944, he produced Language of Vision, a landmark book about design theory, followed by the publication of six Kepes-edited anthologies in a series called Vision + Value as well as several other books. -

Exhibitions Photographs Collection

Exhibitions Photographs Collection This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 24, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Generously supported with funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art 10 Art Museum Drive Baltimore, MD, 21032 (443) 573-1778 [email protected] Exhibitions Photographs Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Exhibitions............................................................................................................................................... 7 Museum shop catalog......................................................................................................................... -

Harry Seidler: Modernist Press Kit Page 1

Harry Seidler: Modernist Press Kit Page 1 press kit Original Title: HARRY SEIDLER MODERNIST Year of Production: 2016 Director: DARYL DELLORA Producers: CHARLOTTE SEYMOUR & SUE MASLIN Writers: DARYL DELLORA with IAN WANSBROUGH Narrator: MARTA DUSSELDORP Duration: 58 MINS Genre: DOCUMENTARY Original Language: ENGLISH Country of Origin: AUSTRALIA Screening Format: HD PRO RES & BLU-RAY Original Format: HD Picture: COLOUR & B&W Production Company: FILM ART DOCO World Sales: FILM ART MEDIA Principal Investors: ABC TV, SCREEN AUSTRALIA, FILM VICTORIA, SCREEN NSW & FILM ART MEDIA Harry Seidler: Modernist Press Kit Page 2 SYNOPSES One line synopsis An insightful retrospective of Harry Seidler’s architectural vision One paragraph synopsis Harry Seidler: Modernist is a retrospective celebration of the life and work of Australia's most controversial architect. Sixty years of work is showcased through sumptuous photography and interviews with leading architects from around the world. Long synopsis At the time of his death in 2006, Harry Seidler was Australia's best-known architect. The Sydney Morning Herald carried a banner headline "HOW HE DEFINED SYDNEY" and there were obituaries in the London and the New York Times. Lord Richard Rogers, of Paris Pompidou Center fame, describes him as one of the world's great mainstream modernists. This film charts the life and career of Harry Seidler through the eyes of those that knew him best; his wife of almost fifty years Penelope Seidler; his co-workers including Colin Griffiths and Peter Hirst who were by his side over four decades; and several well-placed architectural commentators and experts including three laureates of the highest honour the world architectural community bestows, the Pritzker Prize: Lord Norman Foster, Lord Richard Rogers and our own Glenn Murcutt. -

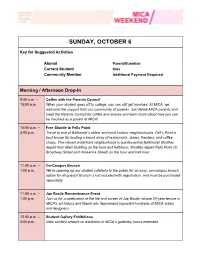

Sunday, October 6

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6 Key for Suggested Activities Alumni Parent/Guardian Current Student Kids 呂 Community Member Additional Payment Required Morning / Afternoon Drop-In 9:00 a.m. – Coffee with the Parents Council 10:00 a.m. When your student goes off to college, you can still get involved. At MICA, we welcome the support from our community of parents. Join fellow MICA parents and meet the Parents Council for coffee and snacks and learn more about how you can be involved as a parent at MICA! 10:00 a.m. – Free Shuttle to Fells Point 3:00 p.m. Travel to one of Baltimore’s oldest and most historic neighborhoods. Fell’s Point is best known for hosting a broad array of restaurants, stores, theaters, and coffee shops. This vibrant waterfront neighborhood is quintessential Baltimore! Shuttles 呂 depart from Main Building on the hour and half-hour. Shuttles depart Fells Point (S. Broadway Street and Aliceanna Street) on the hour and half-hour. 11:00 a.m. – On-Campus Brunch 1:00 p.m. We’re opening up our student cafeteria to the public for an easy, on-campus brunch option for all guests! Brunch is not included with registration, and must be purchased separately. 呂 11:00 a.m. – Joe Basile Remembrance Event 1:00 p.m. Join us for a celebration of the life and career of Joe Basile, whose 24-year tenure in MICA's art history and liberal arts department impacted hundreds of MICA artists and designers. 12:00 p.m. – Student Gallery Exhibitions 5:00 p.m. -

Minimalism 1 Minimalism

Minimalism 1 Minimalism Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work is stripped down to its most fundamental features. As a specific movement in the arts it is identified with developments in post–World War II Western Art, most strongly with American visual arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with this movement include Donald Judd, John McLaughlin, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella. It is rooted in the reductive aspects of Modernism, and is often interpreted as a reaction against Abstract expressionism and a bridge to Postmodern art practices. The terms have expanded to encompass a movement in music which features repetition and iteration, as in the compositions of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and John Adams. Minimalist compositions are sometimes known as systems music. (See also Postminimalism). The term "minimalist" is often applied colloquially to designate anything which is spare or stripped to its essentials. It has also been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and even the automobile designs of Colin Chapman. The word was first used in English in the early 20th century to describe the Mensheviks.[1] Minimalist design The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture where in the subject is reduced to its necessary elements. Minimalist design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this kind of work. -

University of Nsw Harry Seidler Unsw Talk 1 Interactions

UNIVERSITY OF NSW HARRY SEIDLER UNSW TALK 1 INTERACTIONS: ARCHITECTURE AND THE VISUAL ARTS 10 APRIL 1980 INTRODUCTION [0.00] Sydney architect, Harry Seidler, was appointed visiting professor in architecture at the University of New South Wales for the first semester of 1980. He was born in Vienna in 1923. After studies in England he graduated from the University of Manitoba in Canada. Later, he did post graduate work at Harvard University under the founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, and studied design under the painter, Josef Albers. In 1948 Seidler started to practice in Sydney and the many buildings he has completed since then have earned him an international reputation. Amongst his best known buildings is Sydney’s Blues Point Tower, Australia Square and the MLC Centre and Canberra’s Trade Group offices. A recent overseas work is the Australian Embassy in Paris. In this lecture Seidler deals with the interactions between all the visual arts and architecture and the historic basis for this interdependence which he feels should be a guiding and motivating force in architectural design. Modern architecture, as we have come to understand it, has had a history of just over three quarters of a century now. In spite of that, it cannot be said that there is any consensus of opinion about its viability. There’s always been a reluctance on the part of those who practise it and those who criticise it to state any dogma. Those dogmas that have been stated such as “This new architecture is functional, it is logical, it responds to the new technology” are rather obvious and rather facile descriptions of what it’s really all about. -

Friday, October 4

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4 Key for Suggested Activities Alumni Parent/Guardian Current Student Kids 呂 Community Member Additional Payment Required Morning / Afternoon / Daylong 9:00 a.m. – Undergraduate Classroom Visits 3:00 p.m. Stop in to see a MICA class in action! We’ll have selected recommendations for parents, alumni, and all attendees. 呂 10:00 a.m. – 11:00 Campus Tour a.m. Haven’t been on campus in a while? Explore MICA’s expanded footprint in Bolton Hill, from The Gateway to the Mount Royal Station. 呂 11:00 a.m. – Entrepreneurship Initiatives at MICA and Beyond 12:30 p.m. Learn about two of MICA’s most exciting programs focused on creative entrepreneurship: our Up/Start venture competition and the Baltimore 呂 Creatives Acceleration Network (BCAN). 1:00 p.m. – Campus Tour 2:00 p.m. Haven’t been on campus in a while? Explore MICA’s expanded footprint in Bolton Hill, from The Gateway to the Mount Royal Station. 呂 10:00 a.m. – Norman Carlberg Exhibition 5:00 p.m. Norman Carlberg (1928 - 2018) was hired to become MICA's Director of the Rinehart School of Sculpture in 1962 after studying under Director Josef Albers 呂 at Yale University. Over the next 36 years, under Carlberg's tutelage, the school dramatically shifted perspectives, moving from a provincial, figurative-based academy into an internationally esteemed school focused on contemporary art. This exhibition of Carlberg's work - sculpture, photographs, and prints - has been generously loaned by his family, to celebrate his legacy at MICA and to share his genius with his friends, most of whom are his former students, as well as MICA alumni and the Baltimore Community. -

Allen East and West:" a Pretty Dreary Place!

Allen East and West: "A Pretty Dreary Place! by Diane Schwartz Trinity in 1957 for a total cost of added that the change is a long- beds was unanticipated, and ocl. tnit'sthisi procSdgre^puld •Vfirm 1 p "We think it's a pretty dreary $65,000. According to Tilles, they range objective, and to a great place," said Elinor Tilles, cured during the last week of the" ffie^pTaWringy''-paWringy »ndfegiYfrli&sJ »nd»fegiYfrli&sJnn - were originally used for faculty extent would be determined by the summer and the beginning of the centivei" " for students to follow assistant dean for college housing before being converted to college's budget. semester as students cancelled residences, in reference to Allen through with their signed housing student residences. A final decision would be made housing agreements. She said she contracts. East and West. A tentative plan to The conversion involved the by Tilles, Smith, Robert did not know if this was the start of discontinue their use as student Smith said that he would like to removal of kitchen facilities from Pedemonti, treasurer-comptroller, a trend that would continue for try for more singles ac- dorms is under consideration. the apartments. In recent years, and Riel Crandall, director of other years. She said she does want Students currently residing in comodations if the school ever does other changes have been made, buildings and grounds, with the to "loosen up" present housing acquire additional buildings. He the dorms expressed including the construction of fire approval of Theodore Lockwood, accomodations, and reduce the dissatisfaction with the buildings. -

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS BROAD AND CHERRY STREETS • PHILADELPHIA 163rd ANNUAL REPORT 1968 Cover: Space Frame D by Edna Andrade The One Hundred and Sixty-Third Annual Report of THE 'PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS For the Year 1968 Presented to the Meeting of the Stockholders of the Academy on February 3, 1969. OFFICERS Frank T. Howard (to May) . .. .... ...... .... ....... President Edgar P. Richardson (from May) Alfred Zantzinger (to May) .......... ...... ..... Vice President James M. Large (from May) C. Newbold Taylor (to May) . ... ...................... Treasurer Thomas P. Stovell (from May) Joseph T. Fraser, Jr .. ..... ................ ..... Secretary BOARD O F D IRECTORS Mrs. Bertram D. Coleman Henry S. McNeil Robert O. Fickes John W. Merriam Francis I. Gowen C. Earle Miller David Gwinn Frederick W. G. Peck J. Welles Henderson (resigned Evan Randolph, Jr. in February) Edgar P. Richardson (ex officio) Frank T. Howard James K. Stone R. Sturgis Ingersoll Thomas P. Stove II Arthur C. Kaufmann C. Newbold Taylor Henry B. Keep Franklin C. Watkins James M. Large William H. S. Wells James P. Magill (Director Emeritus) Andrew Wyeth Alfred Zantzinger Ex officio Representing Women's Committee: Mrs. Albert M. Greenfield, Jr., Chairman Representing City Council: Representing Faculty: David Cohen Jimmy Leuders (to May) Robert W. Crawford Louis Sloan (from May) Joseph L. Zazyczny Solicitor: William H. S. Wells, Jr. 2 STANDING COMMITTEES Collections and Exhibitions Ex officio James M. Large, Chairman Mrs. Elizabeth Osborne Cooper Mrs. Leonard T. Beale Mrs. Marjorie Ruben William H. S. Wells, Jr. Mrs. C. Earle Miller Mrs. Herbert C. Morris Mrs. Evan Randolph Alfred Zantzinger Jimmy C. -

Traces of the Bauhaus in Sydney: Modernist Heritage and Artistic Experiment

P R E S S R E L E A S E 31 October 2014 Traces of the Bauhaus in Sydney: Modernist heritage and artistic experiment The international exhibition and publication project “Expanded Architecture” is devoted to Australian architectural icons of modernism and casts current artistic perspectives on Bauhaus ideas and its advocates How can temporary artistic interventions be used to think about and experience architecture in new and different ways? That question will be pursued on November 7th, 2014, as the project “Expanded Architecture” presents the exhibition “Temporal Formal at Seidler City” as part of this year’s Sydney Architecture Festival. For one night, the lobbies of three architectural icons of modernism in Sydney’s central business district will become the subject of artistic exploration and the scene for art installations, sound experiments and performances. On the next day, a research symposium will be held by the curators – Dr. Claudia Perren, Director of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, and Sarah Breen Lovett, artist from Sydney – at the Museum of Sydney. Three of the most important buildings of Australian modernist architecture will be the focus. The high-rise office buildings Australia Square (1965-67), Grosvenor Place (1982-88) and Castlereagh Centre (1984-89) were designed by the Austrian-born Australian architect Harry Seidler. Harry Seidler, a student of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, is considered one of the pioneers of modernism in Australia. For his buildings, Seidler (1923–2006) frequently worked together with artists like Bauhaus master Josef Albers, along with American greats such as Frank Stella, Sol LeWitt, and Norman Carlberg, thereby drawing inspiration from their treatments of geometries and patterns. -

Scroll 3: on Site 2 SCROLL 3 : on SITE 2016 Printed by Free, Inprintandonline

Scroll 3: On Site Scroll is an annual publication, published by The Contemporary and produced entirely by its intern staff. Each issue of Scroll explores a different cultural topic related to the mission and efforts of The Contemporary and is available, for free, in print and online. Printed by Schmitz Press Copyright © 2016 by Contemporary Museum, Inc. contemporary.org All rights reserved. 2 SCROLL 3 : ON SITE 2016 ON SITE 2016 2 SCROLL 3 : 2016 SCROLL 3 : ON SITE 3 ON SITE 3 2016 SCROLL 3 : Scroll 3 Staff Allie Linn is an artist and May Kim is finishing up Brandon Buckson is an writer in Baltimore. She her graphic design BFA artist from East Baltimore. co-runs Bb, an interdisci- at Maryland Institute He mentors youth in West plinary project and gallery College of Art (MICA). Baltimore with the aim of space in the Bromo Arts inspiring hope and change District. through art. About Scroll 3: On Site In the summer of 2015, The Contemporary moved its offices to 429 N. Eutaw Street, a building that holds a lot of history. The iconic Art Deco facade and black glass “Charles Fish & Sons” sign out front directly point to the building’s time as a department store, but less visible are the many other ventures it has held. Deliberate research into the space introduced us to the building’s surprising history as one of the nation’s first dental schools. Impromptu conversations with local residents informed us of countless other projects once housed inside: a clothing store, a church, a campaign office, a popup exhibition space, and a nightclub. -

Architecture Technology and Process

Alis-Fm.qxd 5/8/04 11:25 AM Page i ARCHITECTURE, TECHNOLOGY AND PROCESS Alis-Fm.qxd 5/8/04 11:25 AM Page ii For Ursula and all the other generous friends, both near and far, professional and non-professional, who have given me so much encouragement over the years Alis-Fm.qxd 5/8/04 11:25 AM Page iii ARCHITECTURE, TECHNOLOGY AND PROCESS Chris Abel Alis-Fm.qxd 6/8/04 7:02 PM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2004 Copyright © 2004, Chris Abel. All rights reserved The right of Chris Abel to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, e-mail: [email protected].